● DILATED AND HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHIES

Cardiomyopathies are diseases of the myocardium affecting the left, right, or both ventricles and are commonly associated with abnormal cardiac function. Myocardial changes associated with cardiomyopathy are typically not the result of a structural cardiac malformation.

Generally two types of cardiomyopathies exist: dilated and hypertrophic. In the fetus and neonate, a cardiomyopathy is a very rare event, and the literature presents different causes and prevalence in this population (1). Some forms of fetal cardiomyopathy may not be significantly relevant in the postnatal period, and postnatal cardiomyopathy may not develop in the fetus (2). The incidence of cardiomyopathy is less than 1% of all neonates with congenital heart disease.

● DILATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

Ultrasound Findings

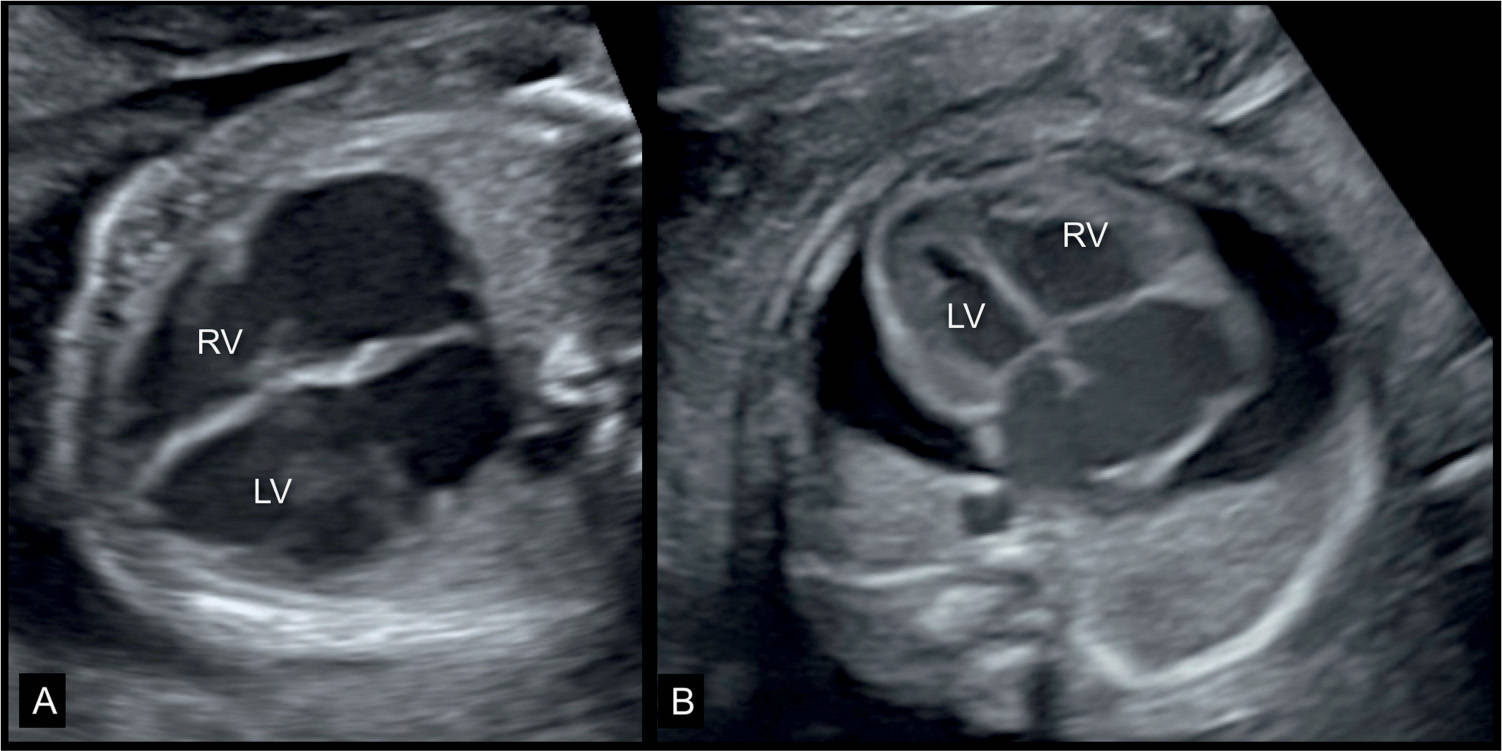

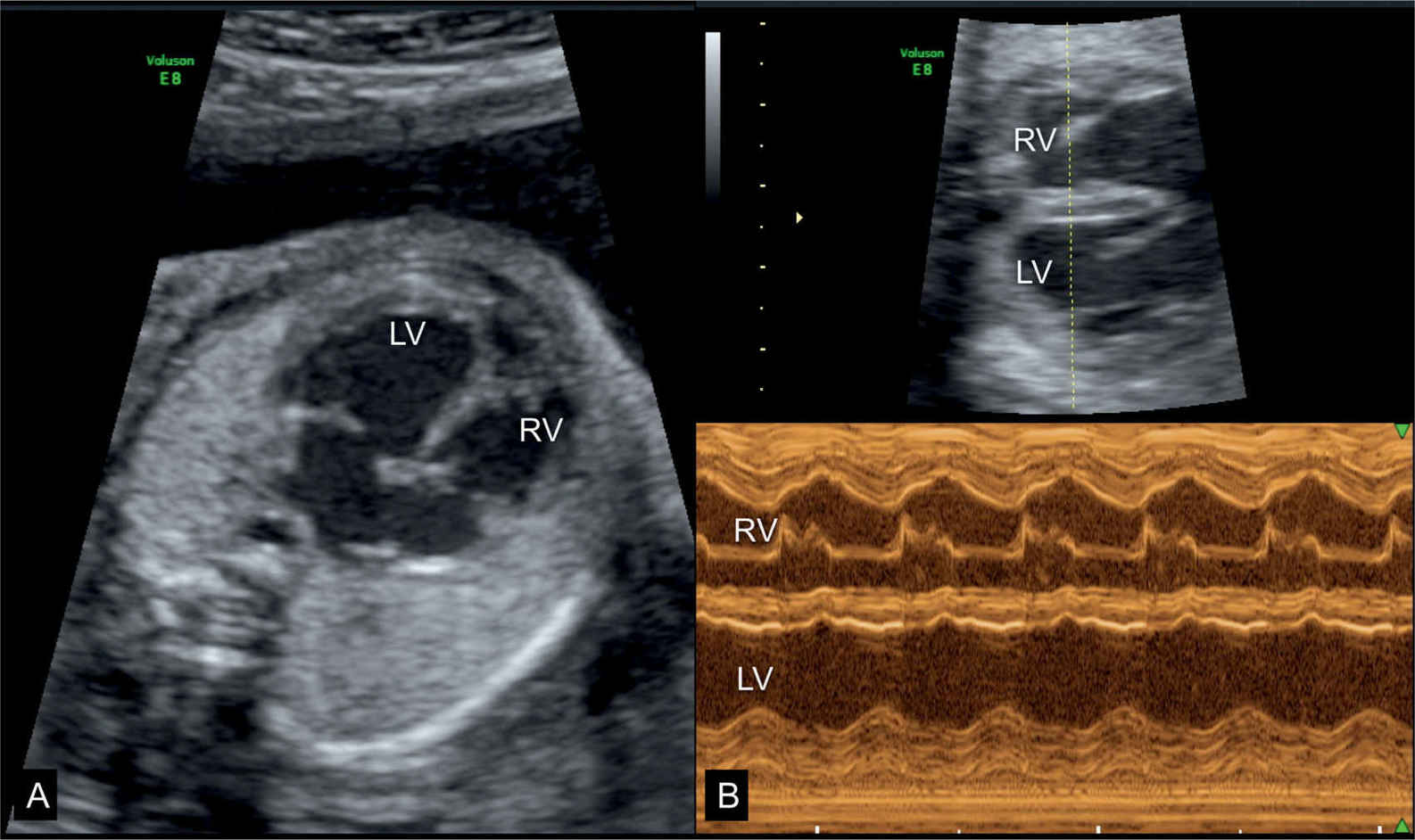

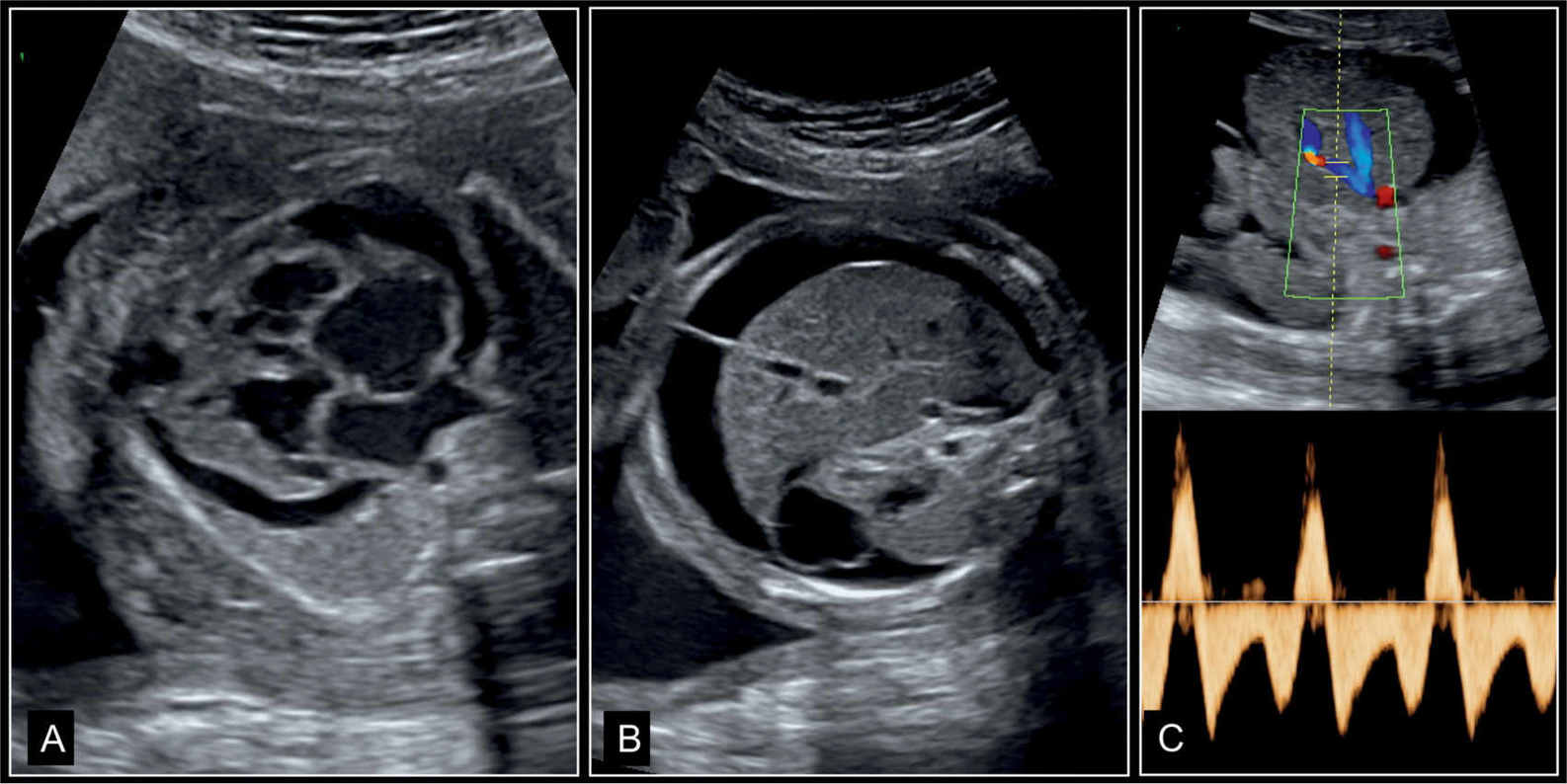

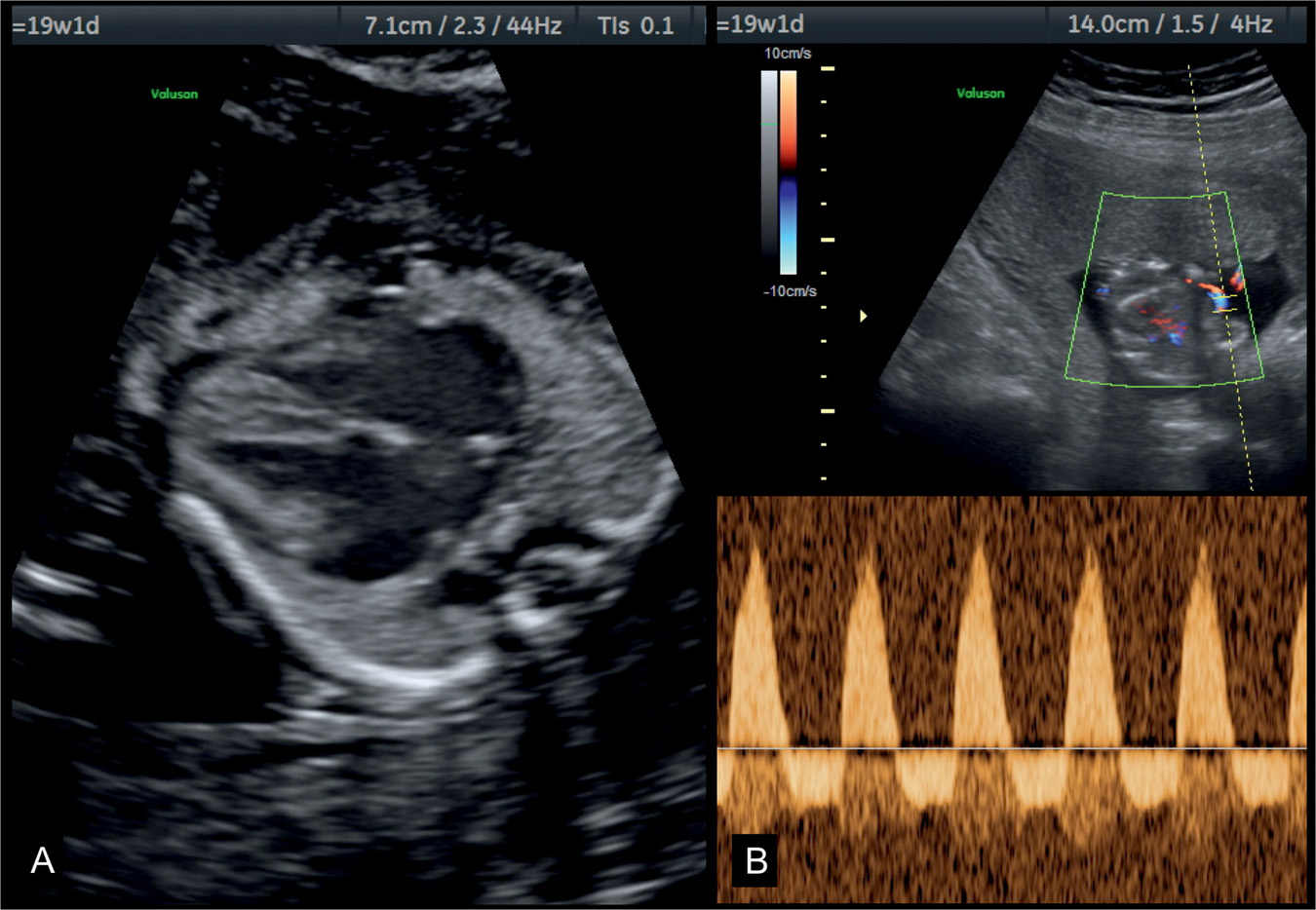

Dilated cardiomyopathy is generally recognized owing to an enlarged heart with a dilated left ventricle, right ventricle, or commonly both ventricles (Figs. 32.1 to 32.4). Ventricular dilation can be quantified by cardiac measurements (e.g., cardiac width, cardiothoracic ratio) (3). Ventricular wall contraction is reduced and can be objectively assessed by M-mode measurements, demonstrating reduced shortening fraction. Pericardial effusion can be found (Figs. 32.1 and 32.3). Comprehensive examination of the four-chamber plane and the great vessels usually does not reveal any major structural anomaly, even if occasionally a small ventricular septal defect is found. Color Doppler shows in many cases mild or severe regurgitation of the valve of the affected ventricle(s). The dilation and the insufficiency increase with advancing gestation and may result in significant ventricular dysfunction and fetal hydrops (Fig. 32.3). Cardiac failure with hydrops is, in some cases, the first detected sign leading to the diagnosis (4).

Figure 32.1: Two fetuses (A and B) at 23 weeks’ gestation with dilative cardiomyopathy and cardiomegaly. Note in A the grossly dilated cardiac chambers. The fetus also had facial dysmorphism (not shown) and fetal death occurred 2 weeks following the ultrasound examination. The fetus in B had a parvovirus B19 infection, anemia and suspected myocarditis with dilated heart, and pericardial effusion. LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 32.2: Dilative cardiomyopathy in a fetus at 25 weeks’ gestation shown at the four-chamber view (A) and the corresponding M-mode (B) at 33 weeks’ gestation. Hypokinesia of the left ventricle (LV) is noted on the M-mode spectrum in B. At 25 weeks’ gestation tricuspid and mitral regurgitation were present but disappeared in the third trimester. Postnatally no etiology was found and the child is currently awaiting cardiac transplantation at 9 months of age. Suspected Coxsackie infection could not be confirmed. RV, right ventricle.

Figure 32.3: Dilative cardiomyopathy with fetal hydrops in a fetus at 27 weeks’ gestation. A represents the four-chamber view, B represents an axial view of the abdomen, and C represents Doppler of the ductus venosus. Note the pericardial effusion and cardiomegaly in A, and skin edema and ascites in B. In C, Doppler of ductus venosus shows end-diastolic reverse flow. All these are signs of an abnormal cardiovascular score and poor outcome (see Fig. 14.22). Fetal death occurred few weeks later.

Figure 32.4: Four-chamber view (A) and umbilical artery Doppler (B) in a fetus with dilative cardiomyopathy at 19 weeks’ gestation with hypoxemia. Note in A the presence of cardiomegaly with dilated cardiac chambers and small lungs. The fetus had severe growth restriction and reverse flow in the umbilical arteries as shown in B.

Associated Cardiac and Extracardiac Findings

When a dilated cardiomyopathy is suspected, the big challenge is to find out the underlying cause. A detailed ultrasound examination of the fetus is recommended, combined with Doppler investigation of the fetal arteries and precordial veins. A significant number of cases remain “idiopathic.” Associated extracardiac findings may give a hint to the possible cause, as in the presence of echogenic foci in the liver or dilated ventricular system in the brain, which may suggest infectious etiologies. Cardiomyopathy in monochorionic twins is generally noted in the recipient twin in twin–twin transfusion syndrome, where the right ventricle is primarily affected (5). Anemia (isoimmunization or parvovirus) (Fig. 32.1B) may be the cause of cardiomyopathy with associated hydrops and increased peak velocities in the middle cerebral arteries. The presence of bradycardia with heart block may suggest the presence of maternal autoantibodies (6). Maternal autoantibodies can cause dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without heart block (6). Chromosomal assessment is recommended, including microdeletion 22q11.2 or microarray (see Chapter 4). A family history and genetic counseling may reveal whether a familial inheritance is present. Comprehensive detailed screening of the fetus and placenta with color flow mapping may reveal an unexpected arteriovenous malformation. Follow-up examination may show the presence of intermittent tachycardia, sometimes not present during the first evaluation of the heart. Metabolic diseases are so rare and generally impossible to exclude prenatally if the family history is not informative (1, 2, 4).

Pitfalls and Differential Diagnosis

Dilated and severe cardiomegaly can be present in association with many conditions and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Dilated right ventricle is found in Ebstein anomaly and tricuspid dysplasia. Left ventricular endocardiac fibroelastosis with patent but insufficient mitral valve is one of the main differential diagnoses. Bilateral atrioventricular valve insufficiency can be found in myocarditis, volume overload, and other conditions, and some of these conditions may lead to cardiomyopathy. Cardiomyopathy may resolve with advancing gestation with normal cardiac function postnatally. A transient fetal infection may be involved when cardiomyopathy resolves prenatally.

● HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY

Ultrasound Findings

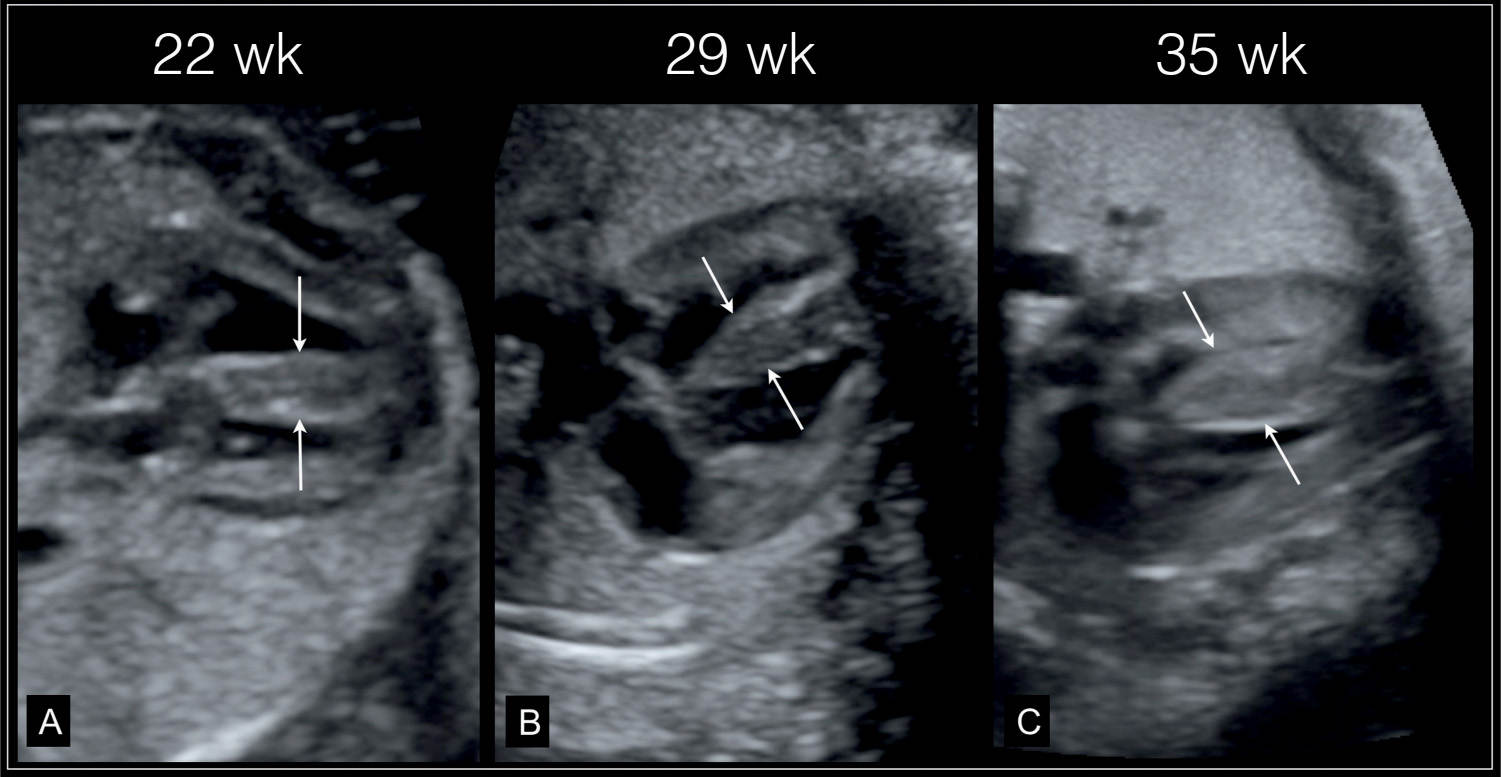

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is generally recognized owing to an enlarged heart in association with ventricular wall hypertrophy of one or generally both ventricles (1) (Figs. 32.5 to 32.7). The lumen of the affected ventricle(s) can be decreased. A pericardial effusion can be found. The comprehensive examination of the four-chamber view and the great vessels does not reveal any major structural anomaly correlating with the severity of the finding. An obstruction of the inflow or outflow tract can be found, leading to aliasing on color Doppler and increased velocities measured on pulsed Doppler. Regurgitation of the atrioventricular valves can occasionally be found but is not as common as in the dilated type. Ventricular hypertrophy and cardiac compromise increase with advancing gestation and can lead to cardiac failure, hydrops, and in utero death.

Associated Cardiac and Extracardiac Findings

Similarly to dilated cardiomyopathy, identifying the underlying cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can be challenging. A comprehensive examination of the entire fetus can help in detecting additional signs, which may lead to the diagnosis. Storage diseases, which are rare and difficult to diagnose in utero, can be a cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and are associated with hepatomegaly, which results in increased abdominal circumference or changes in liver echogenicity. Many causes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy remain “idiopathic.” The most common condition found in association with a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is diabetes mellitus, especially with poor glycemic control. This occurs in the last trimester of pregnancy. Another known condition is bilateral renal agenesis or dysplasia (Fig. 32.6) with oligohydramnios, leading to a thickening of the myocardium. The pathogenesis is not known but may be due to either hypertension of renal origin or pulmonary hypertension with lung hypoplasia. Chromosomal assessment is recommended including microarray (see Chapter 4), but other genetic syndromes should also be considered. Noonan syndrome has been reported in association with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A family history and genetic counseling may reveal whether a familial inheritance is present. When consanguinity is present, the occurrence of a storage disease should be sought. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can occur in twin–twin transfusion syndrome, especially in the recipient twin, probably due to chronic volume overload.

Figure 32.5: Primary hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A thickened nuchal translucency was found at 12 weeks’ gestation. Fetal echocardiography at 22 weeks’ gestation (A) revealed thickened myocardium (arrows), which continued to increase in thickness at follow-up at 29 weeks (B) and 35 weeks (C). Postnatally hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was confirmed with unknown etiology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree