trauma, but do not deliver at that time, continue with significant risk of increased morbidity and mortality throughout their pregnancy and therefore require close monitoring (13).

Systolic arterial pressure decreases by 0 to 15 mm Hg, whereas diastolic pressure declines by 10 to 20 mm Hg, creating a widened pulse pressure. These changes are the result of diminishing peripheral vascular resistance and should not be mistaken as evidence of hypovolemia during the first two trimesters of pregnancy. During the third trimester, blood pressure gradually increases, returning to pre-pregnancy levels near term (2,7,9,22,23). Hypertension, systolic or diastolic, is never expected during pregnancy and, if present, may either be a response to pain, anxiety, or injury or be the result of a direct complication of pregnancy such as pregnancy-induced hypertension (9).

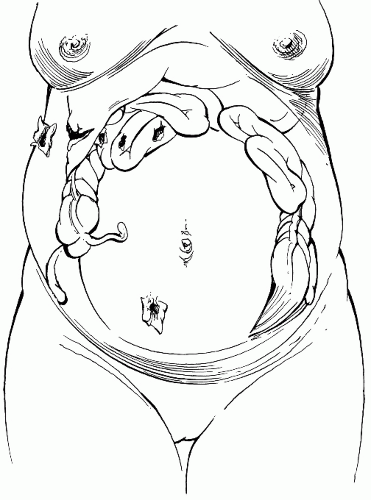

FIGURE 4.1 Compartmentalization of intestines during pregnancy and sites of gunshot wounds above and below the umbilicus. |

would normally cause vasoconstriction. This altered response causes the skin to be warm and dry, instead of cool and clammy which would be expected during hypovolemic shock (9). In addition, central venous pressure, normally approximately 9 cm H2O in the nonpregnant patient, gradually decreases throughout pregnancy until it reaches 4 to 6 cm H2O during the third trimester (4,7,14,24). Venous hypertension in the lower extremities is present during the third trimester.

uterus may protect the abdominal viscera from injury to the lower abdomen, but penetrating wounds to the upper abdomen may injure many loops of tightly crowded small intestine (Fig. 4.1). In addition, stretching of the abdominal wall alters the normal response to peritoneal irritation, at times masking significant intra-abdominal organ injury. Decreased gastric emptying increases the possibility of aspiration during trauma and intubation, therefore early gastric tube decompression is important in order to prevent aspiration of gastric contents (1,7,9,22,24,25). Position of the patient’s spleen and liver is essentially unchanged by pregnancy.

TABLE 4.1 Physiologic and Anatomic Changes in Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When an external deforming force is applied to the abdomen, shearing of the uteroplacental interface occurs. Shearing is further aggravated by the increased intrauterine pressure that results from impact (10,15). Signs and symptoms suggesting abruption include vaginal bleeding, uterine tenderness or contractions, fetal heart rate abnormalities, and fetal death. Although the presence of these symptoms is significant, the absence of symptoms following trauma does not exclude the possibility of placental abruption (3,27,28,29). Most cases of significant abruption can be identified by clinical signs or electronic fetal monitoring within 4 to 6 hours of the traumatic event (15,23,30), however, even in minor abdominal trauma, significant placental abruption can occur without significant symptoms. This supports the importance of fetal monitoring after abdominal trauma (20). Cases of abruptio placentae have been reported to occur up to 5 days following severe trauma (29,31).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree