Valid comparisons of infant mortality over time or between different countries or geographic regions require acceptance and application of standard definitions, complete and reliable data collection, and confidence in both the numerator and denominator. The latter two represent challenges when attempting to compare outcomes in countries with vastly different resources, infrastructure for data collection, and cultural expectations and values.

Infant Mortality in the United States and Other High-Resource Countries

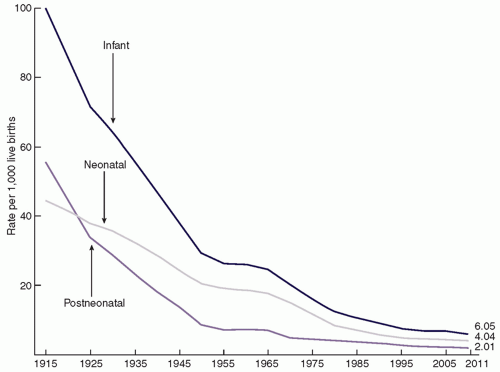

The United States first began to measure and record the IMR in 1915. As shown in

Figure 1.1, during the past 100 years, the US IMR has fallen dramatically from about 100 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1915 to approximately 6 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2011 (

2). Steady improvement in infant survival was interrupted by a plateau in 1955-1959 and again in 2000-2005 when the IMR appeared stalled at approximately 6.9. However, by 2011, the IMR had dropped to 6.05, a 12% decrease from 2005 through 2011 (

2). The progress observed over the past century has been attributed to improved nutrition and sanitation, economic growth, advances in medical care and improved access to care (

3,

4).

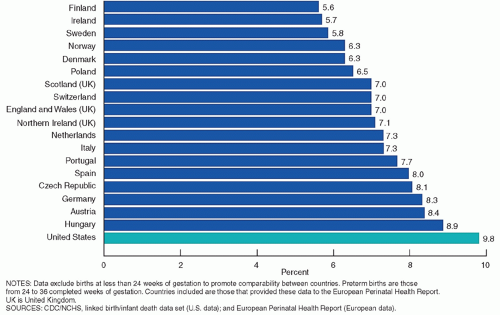

Despite these encouraging statistics, 24,000 US infants died before their first birthday in 2011 (

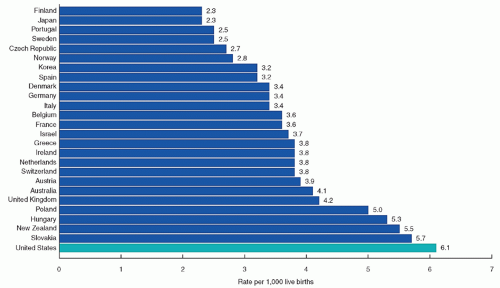

5). Moreover, the IMR in the United States is higher than in many other developed countries. In 2010, the United States ranked 26th among the 29 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD) (

Fig. 1.2), with an IMR of 6.1 (

6). When births at gestational ages under 24 weeks were excluded to better ensure international comparability, the IMR in the United States was 4.2 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, still about twice the IMR for Finland, Sweden, and Denmark, the three countries with the lowest rates after excluding deaths under 24 weeks of gestation. For infants born at 24 to 31 weeks of gestation, the IMR in the United States is comparable to the rates in most European nations; however, the United States had among the highest IMR for preterm infants born between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation and the highest rate of infant death at 37 weeks and above (2.2 per 1,000 live births in 2010) among the OECD countries (

6).

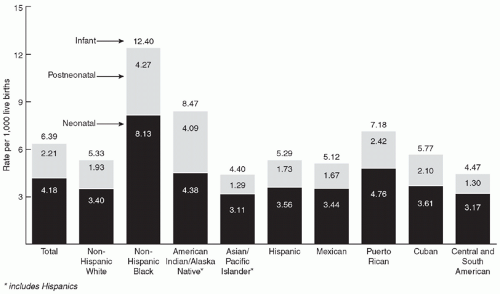

Between 2005 and 2011, the decline in IMR was 16% among black mothers, a larger drop than that observed for other racial or ethnic groups. Nonetheless, large disparities by race and ethnicity persist. The IMR for non-Hispanic black infants (12.40) is more than twice that of non-Hispanic white infants (5.33), based on 2009 data (

Fig. 1.3). Infants born to American Indian/Alaska Native and Puerto Rican mothers also have higher rates of infant mortality (8.47 and 7.18, respectively) than do non-Hispanic white infants (

Fig. 1.3) (

2).

Congenital malformations were the leading cause of infant mortality in the United States in 2011, followed by prematurity, LBW, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (

7). While birth defects have been identified as the leading cause of infant death for more than two decades, prematurity/LBW is the leading cause of infant mortality among black infants (

8). Prematurity is associated with multiple causes of death, and when these are grouped together, preterm birth overtakes birth defects as the leading cause of infant death in the United States, accounting for over a third of all infant deaths (

2,

9).

Between 2005 and 2011, there was a drop in mortality associated with congenital malformations, prematurity/LBW, SIDS, and maternal complications, while the mortality from unintentional injuries rose slightly (

6). A 20% decline in deaths attributed to SIDS is worth noting given the education campaign to place infants on their backs to sleep and other recommendations related to the sleep environment. However, some of this remarkable achievement could be related to changes in the way SIDS is diagnosed and reported.

In 2011, neonatal mortality (death in the first 28 days) was 4.04 per 1,000 live births and accounted for about two-thirds of infant deaths in the United States (

2). Neonatal mortality is most often associated with congenital malformations, infection, perinatal asphyxia, preterm birth, LBW, and other perinatal conditions related to prematurity. Similar to overall infant mortality, infants born to non-Hispanic black mothers, followed by those born to Puerto Rican and American Indian/Alaska Native mothers, had the highest rates of neonatal mortality (8.13, 4.76, and 4.38, respectively) (

2).

Postneonatal mortality is most often attributed to SIDS, other sleep-related deaths, congenital malformations, and unintentional injuries. Once again, there are notable racial and ethnic disparities. Postneonatal mortality was more than twice as high for infants of both non-Hispanic black and American Indian/Alaska Native mothers (4.27 and 4.09, respectively) than for non-Hispanic whites (1.93) (

2).

Perinatal mortality is another important measure of pregnancy health and takes into account fetal deaths as well as early (first week of life) neonatal deaths. There are an estimated 1 million fetal deaths reported annually in the United States (

8). Most fetal deaths are caused by chronic asphyxia, congenital malformations, and pregnancy complications, such as placental abruption, diabetes mellitus, and intrauterine infections (

10). Although fetal deaths, including late fetal deaths at or beyond 28 weeks of gestation, did not change significantly between 2006 and 2012, the perinatal mortality rate (fetal or infant deaths at 28 weeks of gestation until 7 days after birth per 1,000 live births) declined 4% from 6.51 per 1,000 in 2006 to 6.26 in 2011 (

11). There was an 8% decline in perinatal mortality for non-Hispanic black women to 10.8 in 2011, with no significant change for non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women (

11). The improvement in perinatal mortality was driven by an 8% drop in early neonatal deaths (deaths under 7 days per 1,000 live births) from 3.55 in 2006 to 3.28 in 2011, seen primarily among non-Hispanic black infants in the United States (

11). Improved and more consistent reporting of fetal deaths is needed to better understand the risks factors associated with perinatal death and develop strategies for prevention.