Yeasts

Differentiating features of yeasts in tissue include size (including size variability), shape of budding, formation of pseudohyphae, and pattern of inflammatory response (eTable 9.2). If only a few organisms are present, diagnostic features may be absent. The differential diagnosis for small yeasts (several µm) includes Histoplasma, Pneumocystis, Cryptococcus, and endospores of Coccidioides and for larger organisms (10 µm or more) includes immature Coccidioides spherules without endospores, blastomycosis (Fig. 9.1), and larger forms of Cryptococcus. When interpreting special stains, care must be taken to avoid artifacts (Fig. 9.2).

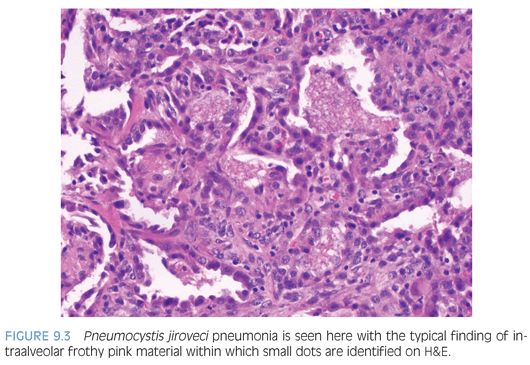

Malnourished infants with Pneumocystis may present as interstitial plasma cell pneumonia, but this is rare in developed countries. The classic histology in immunosuppressed patients is a foamy intraalveolar exudate with numerous organisms in which small dots (nuclei) can be seen on H&E (Fig. 9.3). This is often accompanied by interstitial lymphocytes, plasma cells, and type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia. Necrotizing, granulomatous, fibrosing, and calcifying forms of disease may occur. Two main forms can be identified in tissue: the cyst form containing daughter sporozoites and the trophozoites. Only the cyst walls are positive with GMS (Fig. 9.4). Both the trophozoites (the majority of the organisms) and intracystic sporozoites are negative on GMS, but their nuclear material can be seen in touch preparations stained with Romanowsky stains. On H&E, the differential diagnosis includes pulmonary edema and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP). Pulmonary edema is less eosinophilic with a smooth texture. Secondary PAP is due to defective macrophage clearance of surfactant, resulting in the accumulation of “grungy” material in the alveolar space. Both PAP and Pneumocystis are PAS positive; however, only Pneumocystis is positive on GMS. If in doubt on frozen section, a Romanowsky stain (such as Giemsa) could be performed on a touch preparation.

Viral Infections

Viral infections are seen in the immunocompromised biopsy. The most common patterns are bronchiolitis, diffuse alveolar damage, or interstitial pneumonitis. Aspiration of oral secretions may lead to herpes-related tracheobronchial ulcers. Definitive viral identification is possible by morphology alone or with immunohistochemistry (IHC) for adenovirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpesvirus (eTable 9.3). The differential diagnosis for multinucleated cells in a viral infection includes measles, parainfluenza virus, and herpes/varicella-zoster virus. Other techniques include culture, electron microscopy, and molecular methods.

Mycobacterial Infections

The host response to tuberculosis classically results in granulomas with caseous necrosis. Rare, acid-fast, short, slender rods can be found in the center of the necrotic debris, but tissue processing may alter the cell wall components resulting in low sensitivity of the acid-fast stain. In the most profoundly immunodeficient patients, a granulomatous reaction may be entirely absent, and instead, large numbers of organisms may be present in the midst of necrotic debris with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate, including prominent neutrophils. If stains are negative and the suspicion is high, stains should be repeated on multiple sections, or molecular testing should be considered.

Nocardia is a gram-positive, weakly acid-fast bacterium characterized by thin-branching filaments best seen with GMS. It is associated with necrosis and inflammation with abscess formation and poorly formed granulomas.

NONINFECTIOUS CAUSES OF DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE IN IMMUNOSUPPRESSED PATIENTS

Diffuse lung disease in immunosuppressed patients may have nonspecific patterns of reaction including bronchiolitis obliterans, organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, interstitial pneumonia, pulmonary fibrosis, or pulmonary hemorrhage (Table 9.1).

In bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) (constrictive bronchiolitis, obliterative bronchiolitis), increased fibrous tissue, with or without a chronic inflammatory component, separates the airway epithelium from the smooth muscle, partially or completely obstructing the airway. The bronchiole may be completely replaced by fibrous tissue, resulting in an apparently unpaired pulmonary artery. Because involvement is patchy, the severity of findings in a biopsy does not necessarily correlate with clinical severity. Secondary changes suggestive of obstruction include mucostasis with foamy macrophages and cholesterol clefts. BO may be seen in immunocompetent patients, and the most common overall etiology is postinfectious, particularly following adenoviral infection. BO is also seen in graft-versus-host disease and chronic rejection in lung transplants, in both cases due to infiltration of inflammatory cells recognizing foreign epithelial antigen. It is less commonly seen in other conditions including collagen vascular disease, drug reaction (busulfan), microaspiration, or inhaled toxins.

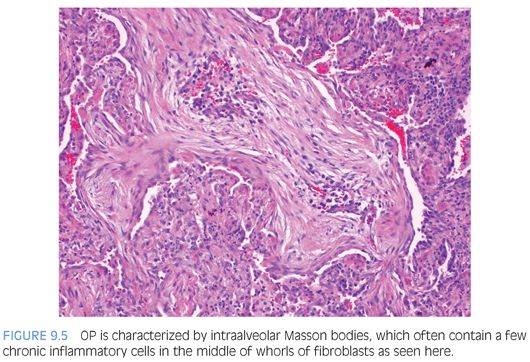

Organizing pneumonia (OP) and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) have similar underlying etiologies (see Table 9.1), and both OP and the organizing stage of DAD have loose connective tissue and reactive fibroblasts. OP is characterized by Masson bodies: balls of loose fibrous tissue and fibroblasts filling alveolar spaces and sometimes extending into distal airways (Fig. 9.5). It is easiest to recognize when flowing between alveoli and is important to diagnose because it may respond to steroid treatment. In early stages, DAD is easy to recognize due to its bright, eosinophilic hyaline membranes lining the alveolar walls. Despite the name, the hyaline membranes may be focal. As fibroblasts begin to organize the membranes (after approximately 5 days), loose connective tissue and fibroblasts accumulate close to the alveolar walls and within the interstitium. Remnants of the hyaline membranes formed in early DAD and the peripheral distribution of fibroblasts distinguish this from OP.

Interstitial pneumonitis and interstitial fibrosis result in widening of the alveolar septa with a spectrum of cellular to fibrous tissue. In interstitial pneumonitis, the alveolar septa are thickened by an influx of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Common infectious causes of interstitial pneumonitis include Pneumocystis and viral infection. It can also be seen in drug reaction and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS), which occurs post–hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). IPS typically occurs in the first 3 months after transplant and is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion when no infectious source can be identified to explain the diffuse pulmonary findings. It is thought to be a reaction to pretransplant conditioning regimens and may present as either interstitial pneumonia or DAD. Interstitial fibrosis widens the alveolar septa with a paucicellular accumulation of collagen, commonly due to radiation therapy or drug effect. Drugs associated with fibrosis include, but are not limited to, busulfan, carmustine, cyclophosphamide, and mitomycin-C.

LUNG TRANSPLANT EVALUATION

Transbronchial biopsies may be performed either for surveillance or to evaluate symptoms. Because findings may be focal, an adequate biopsy is considered to be one with at least five fragments of alveolated tissue, each with at least 100 alveoli. A revised consensus guideline for grading lung rejection was published in 2007 (eTable 9.4); however, some centers still prefer the 1996 classification.2–4 Acute cellular rejection is characterized by a typical mixed inflammatory infiltrate with activated lymphocytes, eosinophils and few neutrophils, and plasma cells. When involving veins, arteries, or lymphatics, this is referred to as acute cellular rejection. When involving the submucosa, it is called airway rejection. The most severe findings should be graded. As the grade increases, eosinophils, neutrophils, and endothelialitis increase. The differential includes PTLD and infection. Airway inflammation may be a component of rejection but can also be seen in infection, especially if neutrophils are predominant and perivascular inflammation is absent. Airway inflammation should also be distinguished from bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT), which is circumscribed, predominantly B cells, and has CD21-positive follicular dendritic cells. Chronic rejection is manifested by BO with or without active inflammation. A morphologic equivalent of antibody-mediated rejection is not well defined in the lung and is not included in the current grading recommendations. Positive staining for C4d by IHC is extremely rare. Microaspiration with macrophages with large vacuoles, foreign body reaction, or granulomas is common in transplant recipients and may precipitate acute rejection.