PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

Any discussion of gynecologic infectious emergencies should begin with a review of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Approximately one million cases of PID per year result in 160,000 hospitalizations, and more than 100,000 surgical procedures annually (

1). Aside from the personal, physical, and emotional distress associated with PID, the financial cost to the individual and to society is staggering. In the United States, the total cost associated with PID and its sequelae in 2006 was estimated at $4.2 billion (

1).

It is important for the clinician to recognize certain risk factors that may be associated with an increased risk of PID. A major risk factor is age. Young women are at greater risk of acquiring PID as a consequence of the greater prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, a lower prevalence of protective chlamydial antibodies, larger zones of cervical ectopy, and a greater penetrability of cervical mucus (

2). Sexually active adolescents are three times more likely to be given the diagnosis of PID than women who are 25 to 29 years old (

1). Multiple sexual partners, a high frequency of sexual intercourse, and a high rate of new partner acquisition within the previous 30 days all appear to increase the acquisition risk of PID (

3). The perception of the role of an intrauterine device (IUD) and the risk of PID is undergoing review. The primary risk centers around the time of insertion (

4). It is presumed to be secondary to the introduction of vaginal and cervical pathogens into the endometrium during IUD insertion. However, even in areas with high prevalence of STDs, the use of an IUD appears to only minimally increase the risk of PID (

4,

5). Other factors that appear to be associated with an increased risk of PID include douching, smoking, and proximity to menses. It has been observed that symptoms develop significantly more often in women with chlamydial or gonococcal salpingitis within 7 days of menses than at other times during the cycle (

6).

Although

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and

Chlamydia trachomatis are considered to be the primary pathogens in PID, other organisms are also isolated from tubal and peritoneal fluids. These organisms include aerobes (

Streptococcus species,

Escherichia coli, and

Haemophilus influenzae) and anaerobes (

Bacteroides bivius, Bacteroides fragilis, Peptostreptococcus, and

Peptococcus) (

7). Other organisms that have been isolated but whose significance is still indeterminate include

Mycoplasma and

Actinomycosis. Finally, tuberculosis is a remote consideration in patients at risk (particularly in underdeveloped countries and immunosuppressed patients). Although PID may be caused by a single agent, infection is frequently polymicrobial. The polymicrobial nature of PID may result when more than one primary pathogen infects the oviductal epithelium or it may result from damage created by a single primary pathogen, resulting in altered host immune defense mechanisms and secondary infections by other bacteria. These secondary invading organisms may be normal inhabitants of the upper vagina that become pathogenic upon contact with damaged tubal epithelium.

PID has always posed a diagnostic dilemma for the examining physician. Mild disease may be misdiagnosed as cystitis or gastroenteritis. Severe disease may be misdiagnosed as ovarian torsion, diverticulitis, or, most commonly, appendicitis. Frequently, this diagnostic dilemma results from the lack of

sensitivity and specificity of the patient’s complaints, physical findings, and laboratory evaluation. Therefore, the index of suspicion for the clinical diagnosis of PID should be high. The CDC has recommended a minimal set of criteria for empiric treatment in order to reduce missed or delayed diagnosis (

8,

9). It may be appropriate to overtreat as undertreatment may cause significant damage to the oviducts, resulting in chronic pelvic pain, infertility, or a future ectopic pregnancy. When no other cause can be identified, empiric treatment should be started in women with pelvic pain and at least one of the following: (a) cervical motion tenderness or uterine/adnexal tenderness; (b) oral temperature >101°F (>38.3°C); (c) peripheral leukocytosis or left shift; (d) abnormal cervical or vaginal mucopurulent discharge; (e) presence of white blood cells (WBCs) on saline microscopy of vaginal secretions; (f) elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and (g) elevated C-reactive protein. Patients with pelvic pain and any of the following are considered confirmed cases: (a) endometrial biopsy with histopathologic evidence of endometritis; (b) laparoscopy findings consistent with PID; (c) laboratory evidence of cervical infection with

N. gonorrhoeae or

C. trachomatis; and (d) imaging studies demonstrating thickened, fluid-filled oviducts with or without free fluid or tubo-ovarian complex.

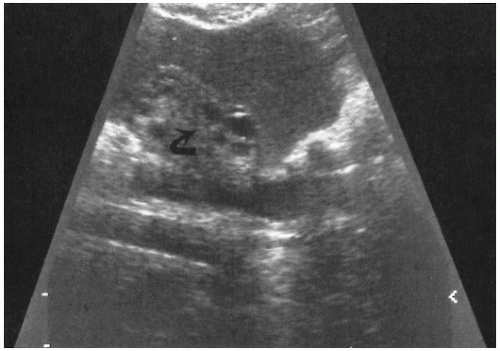

The use of ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scanning may be useful in examining the patient with severe rebound tenderness in whom an adequate pelvic examination is impossible to perform. Ultrasonography may demonstrate echogenic fluid in the pelvis consistent with pus (

Fig. 19.1). CT scanning may demonstrate abscess formation with fluid and air collection (

Fig. 19.2).

When significant uncertainty exists concerning the diagnosis, the “gold standard” has been the performance of a diagnostic laparoscopy. One major study of patients with signs and symptoms of PID undergoing a laparoscopic examination demonstrated that in 65% of the patients, the correct preoperative diagnosis had been made, 23% had normal pelvic anatomy, and 12% had other pathology (appendicitis or endometriosis) (

10).

The decision to admit the patient to the hospital for further evaluation or treatment should be based on certain well-established criteria. These include the following: (a) significant peritoneal signs or rebound tenderness, (b) presence of an IUD, (c) pregnancy, (d) an adnexal mass consistent with a tubo-ovarian abscess (on pelvic examination or diagnostic imaging), (e) gastrointestinal symptoms precluding appropriate outpatient therapy or suggestive of bowel pathology, (f) failed outpatient therapy, (g) nulliparity, and (h) an uncertain diagnosis. Patients with an uncertain diagnosis require further evaluation and institution of therapy. The decision to perform laparoscopy to delineate the disease process may be based on the patient’s severity of symptoms on admission or on her response to antibiotic therapy. If the decision is to initiate treatment with antibiotics and no resolution of symptoms occurs in 24 to 48 hours, or if symptoms increase in severity during this time frame, a laparoscopy should be considered. Treatment regimens for PID are outlined in

Tables 19.1 and

19.2. Appropriate follow-up ensures compliance and resolution of symptoms in patients undergoing the outpatient regimen.

Ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess or leaking tubo-ovarian abscess may present as a serious threat to life. Mortality rate associated with a ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess ranges from 10% to 15%. Appropriate diagnosis and therapy are necessary. When a tubo-ovarian abscess ruptures, endotoxin is released into the systemic circulation. The lipid A portion of the lipopolysaccharide results in the release of numerous factors or mediators: β-endorphins, bradykinin, activators of the complement and coagulation cascades, plasminogen, and histamine. Decreased systemic resistance, a lowpulmonary artery occlusive pressure, and increased cardiac output are noted in the initial stage of shock. As shock progresses, systemic vascular

resistance increases and cardiac output decreases. Microvascular hypoperfusion resulting from microembolization from fibrin degradation products and precapillary sphincteric dilatation resulting from hypoxia result in arterial venous shunting and loss of effective intravascular volume. Myocardial depression results in a diminution of effective cardiac output. Inadequate perfusion of vital organs results in renal dysfunction and accentuated acidosis. It is imperative that the managing physician recognize the presence of septic shock and respond appropriately. The

hypotensive, tachycardic patient with abdominal findings suggestive of diffuse peritonitis, secondary to a ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess, should be managed aggressively with fluid resuscitation. Large volumes of crystalloid should be administered intravenously through two large-bore catheters. If there is a failure to correct hypotension with fluid administration, intravenous sympathomimetic amines should be initiated. Dopamine is the primary agent to be considered. Administered at a dose of 1 to 3µg/kg per minute, dopamine has minor inotropic and chronotropic effects on the heart, with concomitant dilatation of mesenteric, cerebral, coronary, and renal arteries (

11,

12). At dosages between 4 and 10µg/kg per minute, there is a further increase in cardiac output and an increased heart rate. The decision to initiate invasive monitoring for fluid resuscitation should be based on the patient’s response to crystalloid administration and urine output. If blood pressure fails to respond to intravascular volume repletion and sympathomimetic amines and if urine output is not appropriate (>30 mL per hour), then pulmonary capillary wedge pressure monitoring should be considered to prevent the development of adult respiratory distress syndrome. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be initiated promptly to cover the polymicrobial gamut of pelvic pathogens. Preparation should be made for emergency admission to the hospital and laparotomy to remove the ruptured abscess and irrigate the peritoneal cavity. Blood should be sent for type and cross-match, coagulation panel, electrolytes, and blood gases. It is imperative that the physician managing the patient in septic shock from a ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess understand that this is a surgical disease, and pharmacologic intervention is supportive and preparatory to laparotomy.

GONORRHEA

Neisseria gonorrhea requires emergency care in two situations: (a) when it is associated with acute PID and (b) when it is the cause of a disseminated gonococcal infection.

Only 1% to 2% of patients with gonorrhea develop disseminated gonococcal infections. Women appear to be more commonly affected by this presentation than men. This may be explained by the relative lack of symptoms in women harboring

N. gonorrhea in the lower reproductive tract, specifically the cervix. With a breakdown in host immune defense, gonococcemia may occur. With the invasion of the bloodstream, symptoms include fever, chills, and arthralgias. Gonococcal dermatitis-arthritis syndrome develops within 2 to 3 weeks of the primary genital infection. Cutaneous manifestations usually consist of fewer than 25 lesions, usually on the distal extremities and in various stages of development. Lesions begin as pinpoint erythematous macules, which progress to papules, vesicular pustules, or hemorrhagic bullae. Advanced lesions contain a necrotic-appearing center surrounded by an erythematous halo. Rarely are cultures of cutaneous lesions positive for

N. gonorrhea; however, immunofluorescent tissue stains may be of assistance in demonstrating organisms. Blood, urethral, cervical, pharyngeal, and rectal cultures may be of assistance in defining the etiology of the rash. A high index of suspicion is imperative (

13).

With dissemination, the patient may have an acutely inflamed septic joint. Disseminated gonococcal disease is the most common cause of septic arthritis in patients younger than 30 years of age. The arthritis may be monoarticular or oligoarticular. Joints most commonly affected are the knees, elbows, ankles, wrists, and small joints of the hands and feet (

14). The knee is the most commonly involved joint from which the gonococcus is recovered, but this may reflect the relative ease with which this joint is aspirated. The fluid withdrawn from the involved joint usually contains polymorphonuclear neutrophils, but a Gram

stain for Gram-negative intracellular diplococci is positive only 10% to 30% of the time. Cultures likewise are positive in approximately 20% to 30% of cases. Once again, it is imperative that appropriate cultures be obtained from blood, urethral, pharyngeal, rectal, and cervical sites.

With the dissemination of the gonococcus to the heart, endocarditis may develop. Patients may have fever, chills, arthralgias, malaise, fatigue, dyspnea, and chest pain. Most patients have a murmur, and evidence of embolization may be present (conjunctival petechia, Osler’s nodes, and splinter hemorrhages). Occasionally, splenomegaly and arthritis may be noted. Depending on the degree of cardiac compromise, congestive heart failure may be manifested by rales, ascites, edema, or a gallop rhythm on auscultation of the heart. The chest x-ray film may demonstrate cardiomegaly as a manifestation of congestive heart failure. The electrocardiogram may demonstrate left ventricular hypertrophy, bundle branch block, or intraventricular conduction delay. Usually, blood cultures are positive for N. gonorrhea. Echocardiography is useful in determining whether vegetations exist on the heart valves. The most common involvement is of the aortic and mitral valves. Without treatment, the endocarditis is almost always fatal.

Rarely, N. gonorrhea may disseminate to the meninges and cause manifestations of meningitis. Fever and nuchal rigidity in a patient complaining of headache, general malaise, and arthralgias should prompt a lumbar puncture to evaluate for organisms. As with synovial fluid, Gram stain and cultures may be negative, and therefore it is imperative to perform appropriate blood, cervical, urethral, rectal, and pharyngeal cultures for Neisseria.

Hospitalization is recommended for patients with disseminated gonococcal infection. Endocarditis and meningitis should be ruled out. Ongoing CDC investigation demonstrates that fluoroquinolone-resistant gonorrhea is now widespread in the United States. Therefore, this class of antibiotic is no longer recommended for treatment. When bacteremia and arthritis are present, the recommended therapy is ceftriaxone, 1 g intravenously (IV) daily for 7 to 10 days. Meningitis should be treated with ceftriaxone, 1 to 2 g IV every 12 hours for at least 10 days. Endocarditis should be treated with ceftriaxone, 1 to 2 g IV every 12 hours for at least 4 weeks. Depending on the severity of the valvular involvement with vegetations, cardiac surgery with valvular replacement may be necessary. Consultation with the appropriate specialist should be obtained early (

15,

16).