Pulmonary Hemorrhage

DEFINITION, HISTORY, AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

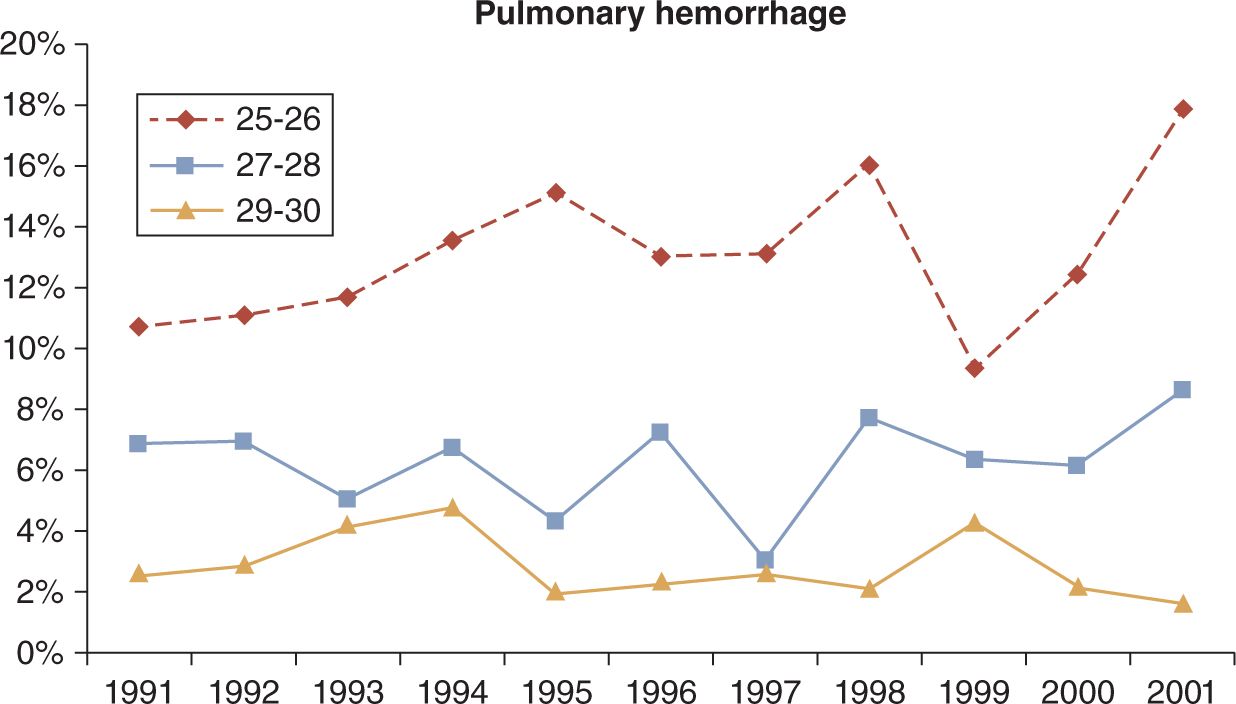

Pulmonary hemorrhage (PH) is the appearance of bright red blood from the trachea in association with acute pulmonary compromise and radiographic changes. Prior to the advent of exogenous surfactant, PH was described as a disorder primarily in term infants, in addition to the occasional very ill preterm infant, with sepsis, asphyxia, hypothermia, Rh disease, intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), heart failure, or coagulopathy. The incidence was estimated at 1.3/1000 births1 and 18/1000 in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants.2 In recent decades, PH is more often a complication of extreme prematurity and is becoming more common as smaller, more immature infants are provided intensive care. PH is most often seen in extremely immature infants after surfactant administration,3,4 particularly when the ductus arteriosus is still patent.5–7 The incidence of PH in VLBW infants in the immediate postsurfactant era was estimated between 3% (according to Braun et al2) and 5.7% (according to Tomaszewska et al3) and has progressively increased since 1998 (Figure 25-1).8 Although once viewed as almost uniformly fatal, the mortality now is closer to 50% in VLBW infants.3 PH accounted for 18% of all deaths in a large series of infants at 23 weeks’ gestation.9

FIGURE 25-1 Incidence of pulmonary hemorrhage (PH) by gestational age groups in the first 10 years after routine use of surfactant. (From St. John and Carlo.8)

Data from the Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms (TIPP) study conducted from 1996 to 1998 in 1202 infants who weighed 500–999 g was reanalyzed in 2007 with respect to the effect of indomethacin prophylaxis on PH.7 The information from this analysis yields a wealth of information on the likely etiopathology of this much-feared complication. The original analysis of TIPP data included pink-tinged endotracheal secretions without accompanying ventilatory worsening or x-ray changes under the definition of PH. Infants receiving indomethacin prophylaxis had no significant reduction on PH compared to control infants.10 This is likely evidence that transient minor bleeding could be due to trauma such as suctioning.11 Infants in TIPP with serious PH were less mature, more likely male and products of multiple gestation, and to have received surfactant on the first day after birth.

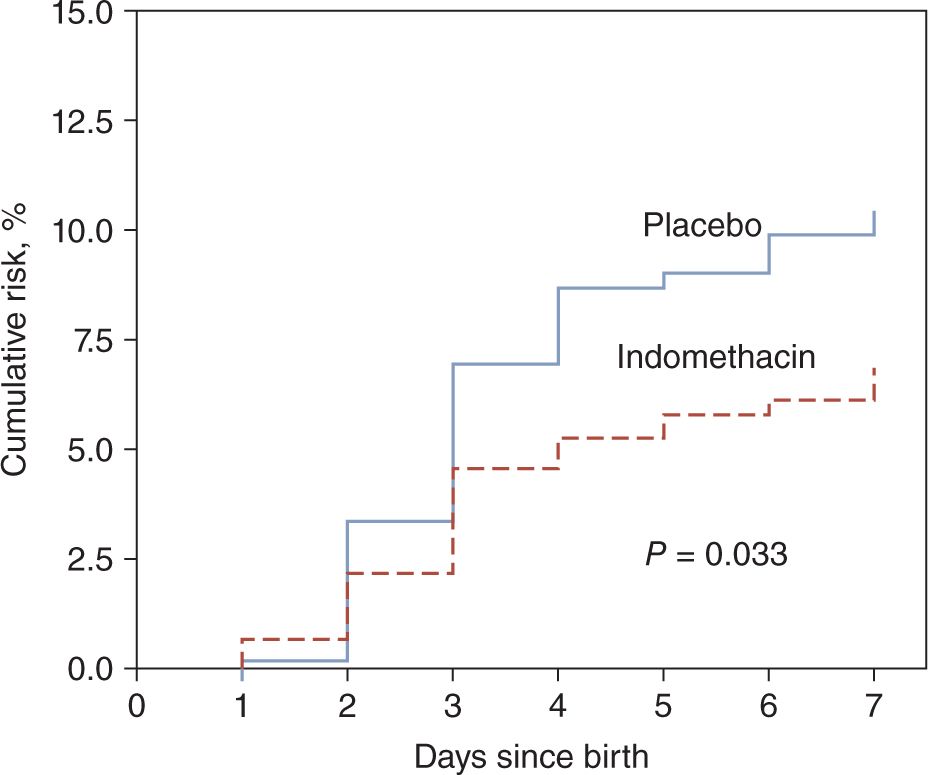

These risk factors along with a protective trend with antenatal steroids have been observed in a number of other studies as well.12–14 Prophylactic indomethacin reduced the incidence of symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) by 50% and serious PH in the first week by 35% (Figure 25-2). After adjustment for other risk factors and accounting for timing of left-to-right ductal shunt, promotion of PDA closure accounted for 80% of the protective effect of indomethacin prophylaxis on PH. This effect became less prominent after the first week, such that the 23% lower risk of PH in the indomethacin prophylaxis group was not significantly different by the end of the hospital stay.7 This fits with the well-recognized phenomenon of ductal reopening after prophylactic use of indomethacin.

FIGURE 25-2 Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative risk for serious pulmonary hemorrhage in prophylactic indomethacin and placebo groups in the Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms (TIPP). (From Alfaleh et al.7)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The frequent occurrence of PH after surfactant administration in the presence of a patent ductus has given rise to the theory that relative pulmonary overperfusion occurs with improvement in compliance and lower pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) after surfactant. “Overtransfusion” was thought as early as 1973 to be related to left ventricular (LV) failure and PH.1 In a study of sequential echocardiography in 126 babies at 23 to 29 weeks’ gestation, PH was associated with greater left-to-right ductal shunting and higher pulmonary blood flow.6 This hyperperfusion is thought to be the culprit in PH. Indeed, pulmonary congestion with certain types of congenital heart defects and the LV failure sometimes observed in asphyxia fit with this hydrostatic theory of PH,15 although coagulopathy that occurs after acidemia and hypoxia could certainly contribute. Coagulopathy from any cause is a risk factor for PH; and in this circumstance, PH may accompany bleeding at other sites.

Increased risk of PH in growth-restricted infants and IUGR infants with elevated nucleated red blood cell (NRBC) counts

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree