Acute Management of Blistering Infants

INTRODUCTION

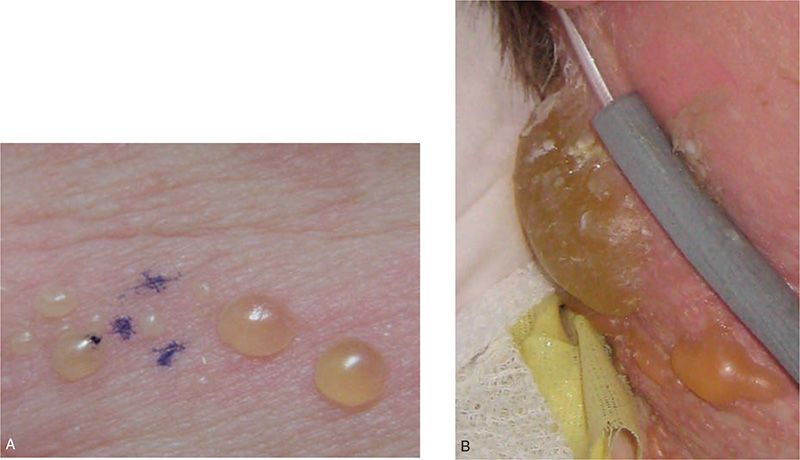

The management of neonates with blistering requires a disciplined approach that includes a broad differential diagnosis of common and rare disorders. For the purposes of this chapter, blistering is broadly defined as primary fluid-filled lesions, such as vesicles, bullae, and pustules, as well as resultant secondary lesions, such as erosions (see Figure 121-1). Blistering lesions are not uncommon in the neonate, and although the majority of etiologies are relatively benign, the rare, life-threatening subset requires that thorough evaluations be considered for all affected neonates.

FIGURE 121-1 A, A vesicle is a fluid-filled lesion 1 cm or less in size; B, the term bulla refers to a larger blister. Vesiculopustules (C) and pustules are filled with purulent fluid. Note the cloudy-to-white appearance of these lesions. D, Erosions result from loss of the epidermis and are often secondary to prior bullous lesions. This neonate with epidermolysis bullosa has a large congenital erosion.

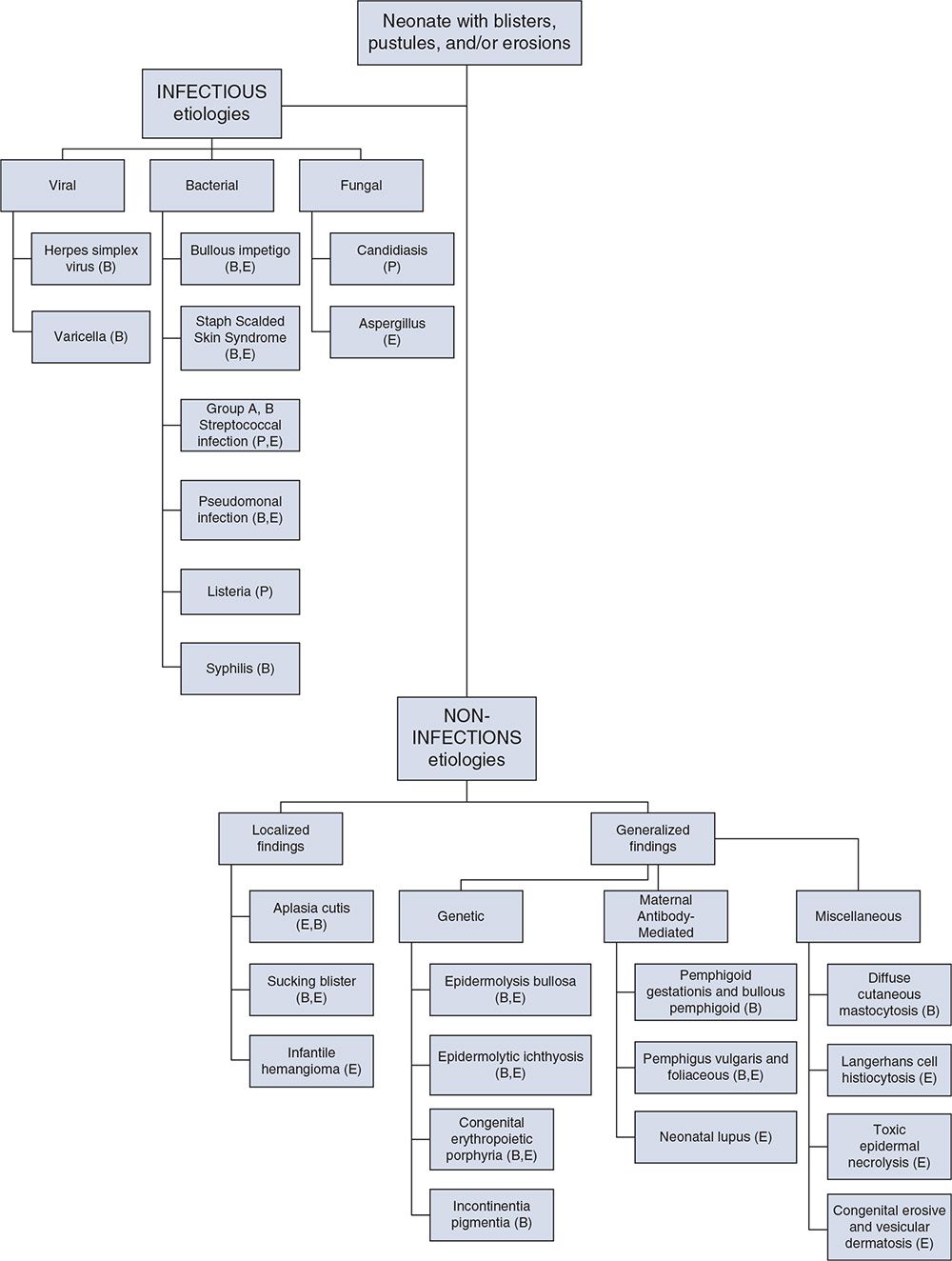

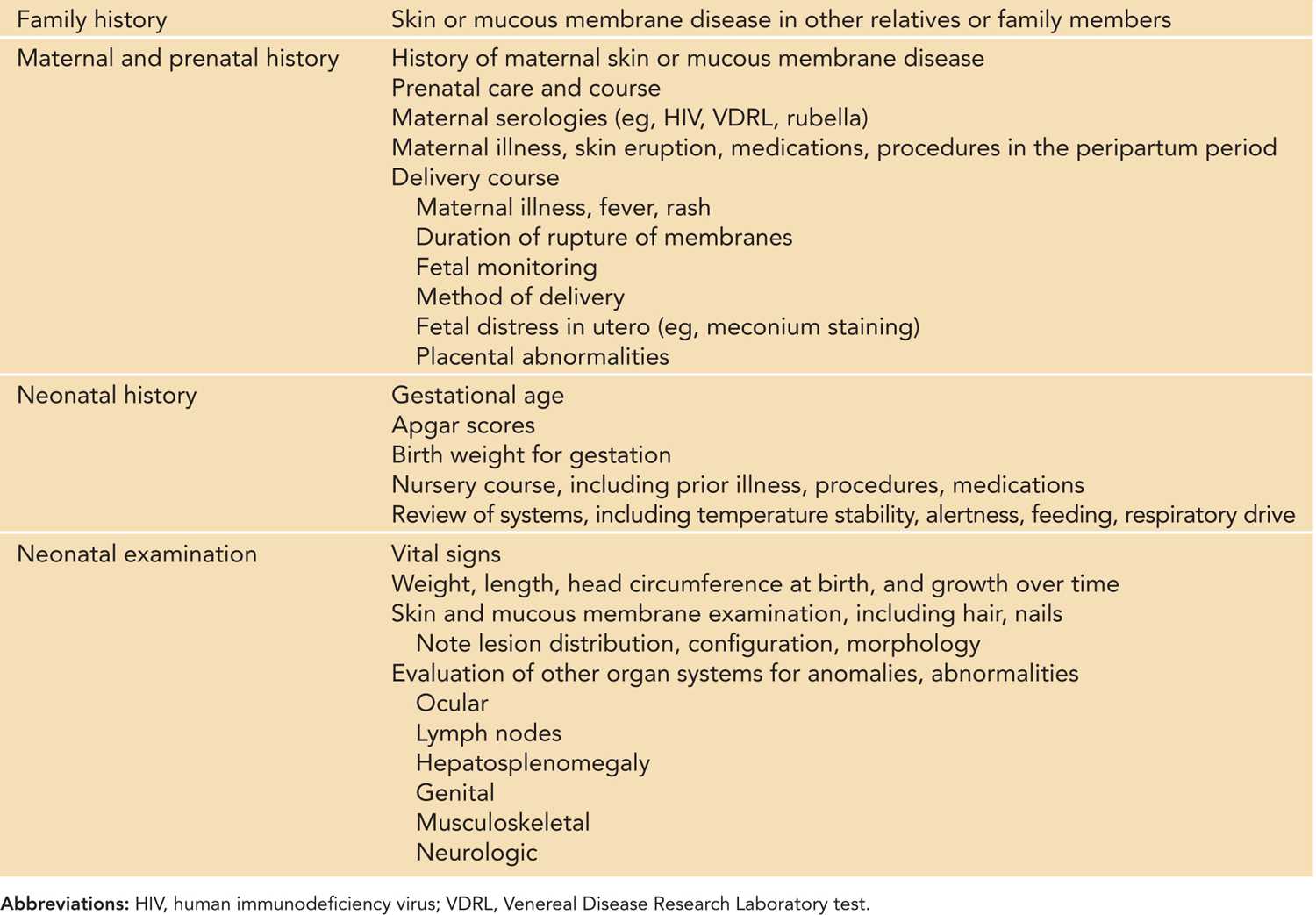

Over 40 different neonatal disorders can present with bullous or erosive skin changes.1 A useful diagnostic algorithm divides these conditions into infectious and noninfectious etiologies, with the latter further divided based on localized or generalized distribution, followed by predominant lesion morphology (see Figure 121-2).2,3 A thorough history, including the prenatal and neonatal course, and physical examination will direct the initial evaluation and treatment. The maternal history should include maternal and family history of skin and mucous membrane disease, prenatal care, maternal serologies, maternal illness, and delivery course (including delivery method and duration of rupture of membranes). If the maternal history is positive for skin or mucous membrane disease, maternal examination is indicated. Neonatal history should include gestation, symptoms of illness, prior procedures, medications, feeding history, neurologic status, and vital sign instability. Skin and mucous membrane evaluation should note lesion distribution, configuration, and morphology. Evaluation of other organ systems may be warranted as indicated (see Table 121-1).1,2

FIGURE 121-2 A diagnostic flowchart for neonates with bullous and erosive lesions, based on the predominant lesion morphology: B, blisters; P, pustules, E, erosions.

Table 121-1 Considerations in the History and Physical Examination of the Neonate With Blisters

The overall goals of management for any neonate with blistering should be to make an accurate and timely diagnosis, halt or minimize the development of new lesions, promote skin healing, treat infection, attend to the infant’s overall well-being (including pain control), and support the family through the evaluation and treatment.

INFECTIOUS ETIOLOGIES

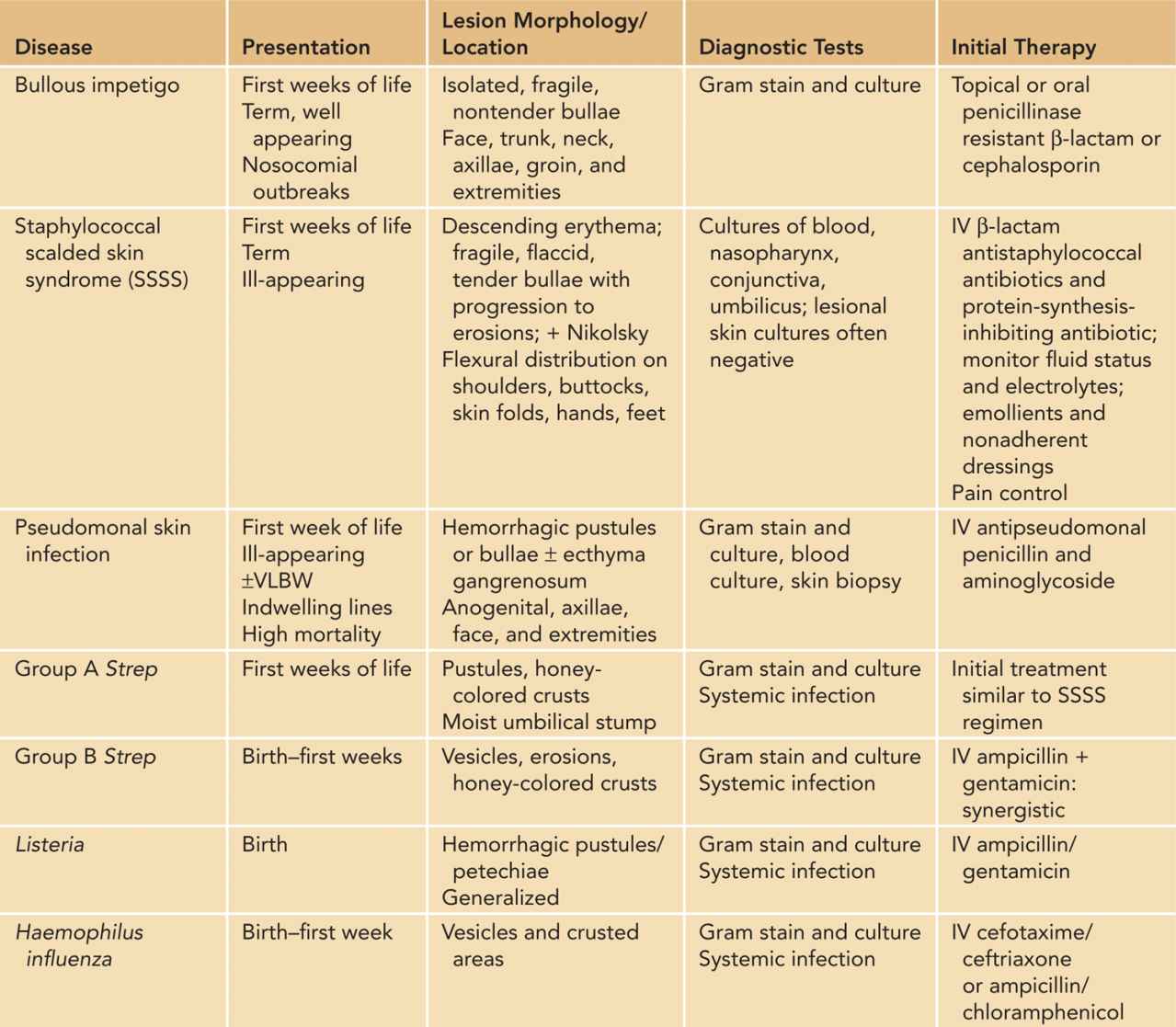

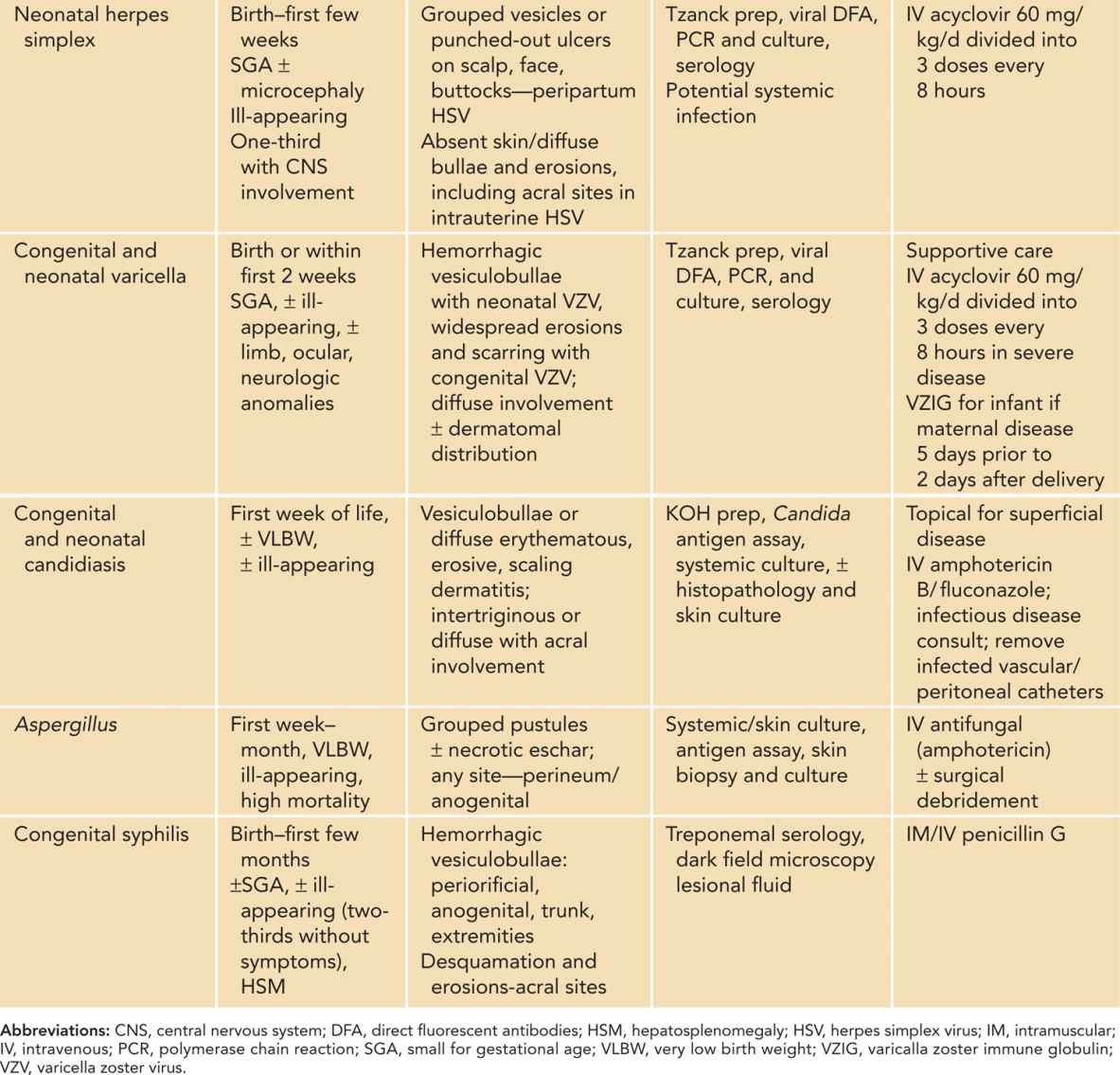

Because of their potentially life-threatening nature, viral, bacterial, and fungal disease should be considered first. Table 121-2 reviews the typical presentation, cutaneous manifestations, evaluation, and treatment of these disorders; the more common and significant infections are discussed here. Multiple diagnoses are typically considered simultaneously, and broad antimicrobial coverage is warranted until infectious etiologies are excluded or confirmed, thereby narrowing treatment.2,4,5

Table 121-2 Neonatal Skin Infections Presenting With Vesiculopustules, Bullae, and Erosions

Herpes Simplex Virus and Varicella Zoster Virus

Clinical Findings

The presentation of neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection will be affected by the timing of maternal infection. For HSV, a maternal history of primary or recurrent genital herpes may be positive, although most women are asymptomatic. A newborn can acquire HSV either transplacentally (intrauterine) or from maternal secretions during the birth process or shortly thereafter (neonatal).

Neonatal signs of intrauterine HSV infection include microcephaly, seizures, chorioretinitis, cutaneous blisters, scar formation, large erosions, and absence of skin as seen in aplasia cutis congenita.

Neonatal HSV infection, with an incubation period ranging from days to 3–4 weeks, presents in 3 clinical patterns: disease limited to the skin, eyes, and oral mucosa (SEM); disseminated infection; and central nervous system (CNS) infection.6 Skin findings of neonatal HSV include small, 2- to 4-mm vesicles with an erythematous base, typically arranged in clusters and concentrated on either the presenting portion of the infant or areas of damaged skin integrity. Lesions may spread locally and progress to erosions or shallow ulcerations. Skin lesions are present in the majority of disseminated and CNS infections.6

Intrauterine VZV infection (fetal varicella syndrome) is exceedingly rare and presents with cutaneous ulceration and scarring in a dermatomal pattern as well as underlying tissue hypoplasia, low birth weight, and abnormalities of the neurologic, musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems. The highest risk for neonatal VZV infection is when maternal infection occurs 5 days prior to 2 days after delivery. Skin findings range from a few pink macules and papules in a well-appearing neonate to diffuse involvement with progressive crops of small erythematous macules, papules, and vesicles with peripheral erythema, progressing to necrotic crust. Disseminated VZV infection can be complicated by pneumonitis, respiratory failure, hepatitis, and encephalitis.4,7

Diagnostic Tests

Definitive diagnosis of HSV or VZV can be made by confirming the presence of virus in skin lesions, using direct fluorescent antibodies (DFA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or viral culture. The highest yield for these studies comes from infected keratinocytes. An intact blister should be unroofed, and the base of the lesion (not blister fluid) should be firmly swabbed or scraped. DFA slides are prepared by scraping the blister base with a number 15 scalpel blade and spreading the material onto DFA slide wells. Viral PCR and culture specimens are obtained by rubbing the specimen swab firmly on the blister base. Viral PCR or culture should also be submitted from other mucosal sites, including the conjunctiva, nasopharynx, oral mucosa, and anal mucosa. A single swab may be used, obtaining the sample in a cephalad-to-caudad direction.4,8

Treatment

In addition to supportive care, treatment is intravenous acyclovir with duration dependent on disease severity. For HSV, standard recommendations are 60 mg/kg/d divided every 8 hours and given 14 days for SEM and 21 days for disseminated or CNS disease.4,9,10 Prolonged courses of oral acyclovir postdischarge have been shown to improve neurologic outcome in neonatal HSV infection.11 In addition to acyclovir, varicella immune globulin, if available, is indicated for infants with neonatal varicella.4,12

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome and Bullous Impetigo

Clinical Findings

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) and bullous impetigo result from exfoliative toxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus. SSSS is a systemic infection with hematogenous spread of the toxin, presenting with acute onset of toxicity, lethargy, vital sign instability, irritability, and poor feeding. Skin signs are erythema with minimal crust around the ocular, nasal, oral, and umbilical sites that progress to diffuse erythroderma and superficial flaccid bullae and erosions. Erythema and bullae are most prominent in skin folds. A positive Nikolsky sign may be produced by applying lateral traction on the skin, resulting in sloughing of the superficial epidermis.13

Bullous impetigo is a localized infection and presents as discrete yellow vesiculopustules that progress to cloudy, nontender, flaccid bullae with an erythematous rim. Lesions easily rupture, producing superficial, shiny, erosions with occasional crust. Infants with bullous impetigo are not systemically ill.13

Diagnostic Tests

Although SSSS is a clinical diagnosis, laboratory confirmation of S. aureus is helpful for both SSSS and bullous impetigo. Swabs for Gram stain and bacterial culture must be obtained from the primary pyogenic site.4 Blood and urine cultures may rarely be positive. Skin biopsy (although rarely needed) differentiates SSSS from toxic epidermal necrolysis and exfoliative graft-vs-host disease and shows a cleavage plane below the stratum corneum with minimal inflammation.

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree