Neonatal Bullous Disorders

INTRODUCTION

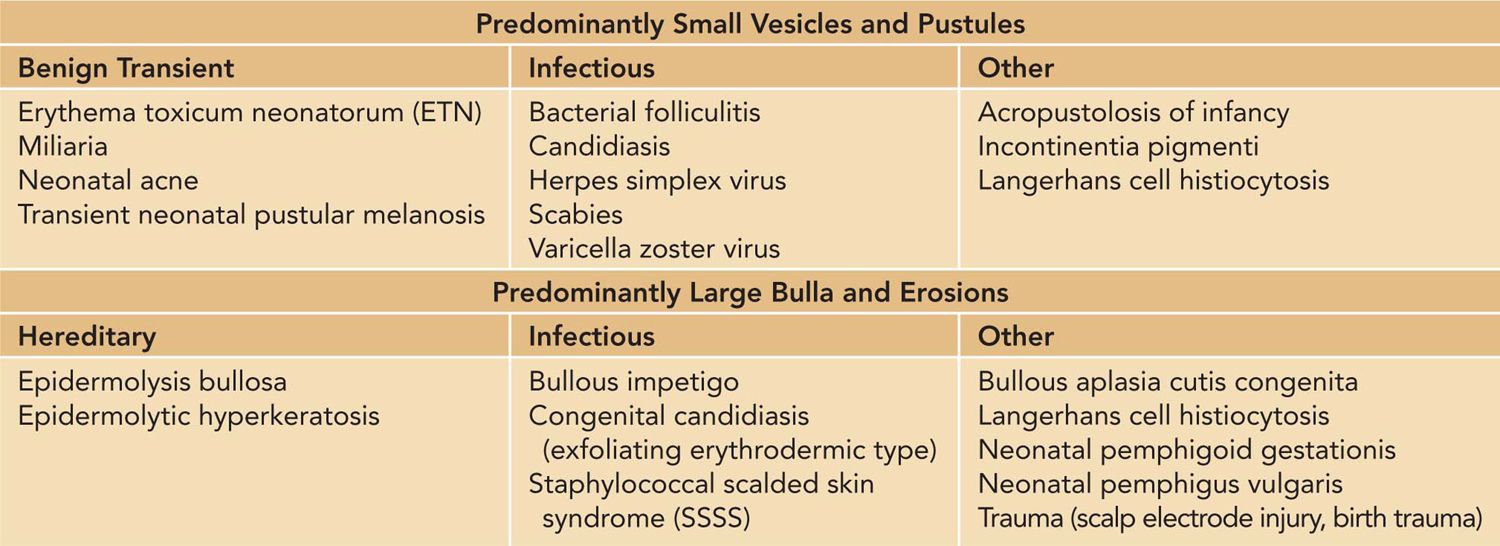

The development of vesicles, pustules, or bullae on the neonatal skin raises a broad differential, which includes infectious, inflammatory, autoimmune, or hereditary causes. The initial clinical presentation of many of these conditions may appear similar. Thus, it is helpful to identify and categorize based on primary morphologic changes (Table 65-1).

Table 65-1 Differential Diagnosis of Neonatal Blistering Diseases

Vesicles are defined as a blister measuring less than 1 cm in size. Blisters larger than 1 cm are termed bullae. Pustules are vesicles with purulent fluid. Vesicles, pustules, and bullae may rapidly rupture, resulting in erosions and ulcerations as the predominant morphology. In other cases, the vesicles and pustules may be miniscule and difficult to discern.

While most of these conditions are benign and transient, there are a few serious, life-threatening conditions that require prompt diagnosis and treatment. Given the broad differential raised by the presence of neonatal blisters, it is helpful to identify the predominant morphology of the eruption and take into account a thorough history and physical.

BENIGN CAUSES OF NEONATAL BLISTERS

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum

Erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN) is 1 of the most common transient, benign skin disorders in the neonatal period. It occurs in about 20% of term newborns,1–4 with some reports5–8 of frequencies as high as 40%–70%. These erythematous papules and pustules are usually not present at birth but will appear during the first day or 2 of life.8

The lesions of ETN are characterized by small papules and pustules overlying an erythematous macule or wheal. The lesions are most frequently found on the trunk and thighs but can also occur on the face and arms.1 The eruption spares the palms and soles.

The differential diagnosis of ETN includes transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM), miliaria rubra, and eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

The diagnosis of ETN is usually made clinically. In some instances, confirmation of the diagnosis can be obtained by Wright staining of a pustule, which would show numerous eosinophils.8,9 Peripheral eosinophilia can be seen in about 15% of patients with ETN, which correlates with the severity of the eruption.8,10

No treatment is needed for ETN. Parents can be reassured that the condition is common, benign, asymptomatic, and transient. Lesions resolve spontaneously without sequelae by 2 weeks of age.

Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis is a benign idiopathic eruption that is usually present at birth or within the first 1 to 2 days of life.8 Unlike ETN, TNPM is seen less commonly. It occurs in about 1% to 5% of newborns, with higher incidences in babies of darker pigmentation.3,4,11

Affected babies may present with small 1- to 3-mm pustules that quickly rupture, leaving behind small, round collarettes of scale that surround hyperpigmented macules. In fact, the pustules may be so superficial and fragile that babies may be born with minimal pustules and only exhibit the collarettes of scale and the hyperpigmented macules. The lesions are usually present on the chin, neck, trunk, and thighs. The palms and soles may also be affected.9

The differential diagnosis includes ETN, miliaria, acropustulosis of infancy, and bullous impetigo. However, these conditions may be differentiated based on clinical morphology. Unlike ETN, TNPM is usually present at birth and has small pustules with little surrounding erythema and superficial pustules that rupture easily, resulting in small, 1- to 3-mm hyperpigmented macules.8 The pustules of acropustulosis of infancy are localized to the hands and feet, whereas TNPM lesions can occur anywhere on the body. Miliaria crystallina vesicules are extremely fine and easily rupture without resultant hyperpigmentation.

The diagnosis is made clinically. A Wright stain of the pustule may be performed, which will show many neutrophils and occasional eosinophils.9

This is a benign, self-resolving condition, and parents should be reassured that the hyperpigmentation will fade spontaneously with time. No treatment is needed.

Miliaria

Miliaria is a common benign, transient condition that can occur in any age group but can also manifest during the neonatal period. It is estimated to occur in about 9%–13% of newborns.12–14

Miliaria is caused by the occlusion of eccrine sweat. Depending on the level of the occlusion that occurs along the sweat ducts, the lesions may range from small clear delicate vesicles to pustules or erythematous papules and nodules. The more common presentation in the neonatal period is miliaria crystallina, which appears as delicate, tiny, clear superficial vesicles, most commonly on the forehead.14 Miliaria rubra is another common eruption in the neonatal period and presents as small erythematous papules and pustules on the face, neck, and trunk.14 Plugging of the eccrine sweat duct occurs in the setting of fever, excessive warming, and underneath occlusive dressings.

The differential diagnosis includes ETN, TNPM, congenital candidiasis, and folliculitis.

The diagnosis is made clinically. Often, there is a history of excessive warming. If the diagnosis is uncertain, a skin biopsy may be performed.

Usually, no treatment is needed for miliaria, and parents can be reassured regarding the benign and transient nature of this eruption. Care should be taken to remove any possible triggers, such as occlusive dressings, or minimizing overheating.

Acropustulosis of Infancy

Acropustulosis of infancy is an uncommon condition of unknown etiology that usually presents during infancy but can present at birth or during the first few weeks of life.15 It is thought that there are 2 forms of acropustulosis of infancy, an idiopathic variant and a postscabetic phenomenon, with the latter more common.15–17 Postscabetic acropustulosis is thought to occur after severe or prolonged scabies infestations.18

Small pruritic vesicles and pustules appear on the palms, soles, dorsal hands and feet. Rarely, atypical forms of this disorder can present with more widespread distribution of the vesicles and pustules. These lesions occur in crops every few weeks (Figure 65-1A, 65-1B).

FIGURE 65-1 A and B, Acropustulosis of infancy. Small, 1- to 2-mm vesicles and pustules are symmetrically distributed on both feet. There is a lack of linear burrows noted. B, The collarette of scale is recognized on the sole after the vesicles and pustules rupture.

The diagnosis can be made clinically based on the history and acral distribution of the lesions. A Wright stain of the lesions may also be performed, which would show polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and some eosinophils. Rarely, skin biopsies may also be performed for diagnostic confirmation. Given that the differential diagnosis includes active scabies infection, it is important to explore this possibility through careful physical examination and performing skin scrapings to look for scabies.17

The differential diagnosis includes active scabies infestation, dyshidrotic eczema, and epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS).

This condition spontaneously resolves within a few years, usually within 18 to 20 months.15 To alleviate symptoms, mid- to high-potency topical steroids can be safely and effectively used.16 If pruritus is causing sleep disruption, oral antihistamines can be taken at bedtime for their sedative effects.19 Dapsone has been reported to be efficacious, but because of the concerns for side effects, this medication should be used cautiously and only reserved for severe cases refractory to other treatments.15

INFECTIOUS CAUSES OF NEONATAL BLISTERS

Superficial Bacterial Infections

Skin infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus can occur during the neonatal period. However, these infections tend to occur within the first few weeks of life and are usually not seen right at birth. More commonly, the infections are superficial and present as impetigo, bullous impetigo, or folliculitis. In some cases, the patient may be severely affected, with bacteremia or staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. A recent analysis from a teaching institution in India found that impetigo was the most common cause of neonatal vesiculobullous disorders at their hospital, comprising 13.5% of cases. Among these, S. aureus was twice as common as group A streptococcus as the etiologic cause.6 It was reported that among children with impetigo, 87% of cases cultured positive for S. aureus.20

Impetigo can occur anywhere on the skin. In nonbullous impetigo, the lesions are erythematous plaques with overlying honey-colored crusts. In bullous impetigo, the lesions are either solitary or clustered pustules and bullae (Figure 65-2).

FIGURE 65-2 Bullous impetigo. Bullae that have ruptured result in superficial erosions.

The differential diagnosis includes other infectious causes of pustules and vesicles. The lesions of bullous impetigo tend to be flaccid and filled with pus. These bullae can rupture easily, resulting in a shallow erosion with a collarette of scale. A diagnostic clue suggesting nonbullous impetigo is the appearance of characteristic honey-colored crusts. The lesions are usually localized or clustered in 1 area, although they may become more widespread.

The diagnosis can be made with Gram stain and culture of the fluid from a pustule.9 Skin biopsies are rarely needed unless the diagnosis is in question. A bacterial culture is helpful because staphylococcal impetigo is indistinguishable from streptococcal impetigo. Furthermore, a culture will also aid in determining antimicrobial sensitivities of the causative strain of bacteria.21

Impetigo can be complicated by cellulitis, bacteremia, and toxin-mediated staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS). The bullous form of impetigo, which is thought to be a localized form of SSSS, is especially at risk for rapid progression to systemic infection. Treatment should be initiated promptly. In the case of bullous impetigo, the recommended therapy is with parenteral antibiotics. If the patient does not exhibit any systemic symptoms and once the lesions have started to improve, the patient may finish the course of antibiotics orally.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a toxin-mediated infection that leads to generalized blistering, erythroderma, and superficial desquamation. It is more commonly seen in the pediatric population. Outbreaks of neonatal SSSS have been reported.22,23

Affected babies are usually fussy and may present with generalized erythema and tender skin. There may be honey-colored crusting localized to perioral skin and desquamation especially noticeable around flexural regions (Figure 65-3). A positive Nikolsky sign is seen, which is characterized by gentle rubbing of uninvolved skin to produce a blister.24 Occasionally, the initial presentation may be a bullous impetigo that rapidly progresses. Exfoliative toxins A and B produced by the S. aureus bacteria, target an important epidermal cell-to-cell adhesion protein, which leads to blister formation.25–27 Infants and young children are most susceptible because of the lack of protective antibodies and immature renal clearance of the toxins.

FIGURE 65-3 A and B, Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. A, Superficial erosions are noted in the flexural regions. B, Honey-colored crusting is seen in the periorificial regions.

Other blistering disorders that may be considered in the differential diagnosis include viral exanthem, toxic epidermal necrosis, congenital candidiasis, and bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. However, clues to the diagnosis of SSSS include the presence of perioral honey-colored crusting and flexural desquamation as well as tender, erythrodermic skin in a very fussy baby.

Often, the diagnosis of SSSS is clinical. This may be supported by the presence of a toxin-producing strain of S. aureus, although the clinical usefulness of this has been questioned because of the lack of sensitivity and specificity.28 Blister formation is secondary to toxins produced by the S. aureus at distant colonizing or infective sites. As a result, cultures taken from the bullae are usually negative. High-yield areas for a positive swab culture are from skin around the nose, eyes, mouth, umbilicus, and any area where there is honey-colored crusting.24 Biopsy can be performed but is rarely required. Histopathology will show an intraepidermal split at or below the granular layer with minimal inflammation.24

Management of SSSS is with antistaphylococcal intravenous antibiotics. Exfoliation may continue for 24–48 hours after antibiotics are initiated.21 Supportive care, including pain control and wound care for the desquamated skin, is the mainstay of therapy. Temperature control and management of fluid and electrolyte balance are necessary if there are widespread erosions.

There is about a 3% mortality for children affected with SSSS.24 Because the blister formation is superficial, the skin will usually heal within 2–3 weeks without scarring. There are usually no long-term sequelae from the disease.

Herpes Simplex Infection

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection during the neonatal period can have significant morbidity and mortality. It is estimated that the incidence of neonatal herpes infection in the United States is 9.6 per 100,000 live births.29 Neonates can acquire HSV in utero, during delivery, or with postnatal exposure. Congenital HSV infection from in utero exposure is rare and is thought to account for less than 5% of cases.30 The clinical features of congenital HSV are similar to other TORCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, HSV) infections. Postnatal infection with HSV is usually caused by contacts with family members or hospital personnel who are shedding HSV. Finally, neonatal HSV is most commonly acquired during delivery through an infected birth canal. There are 3 types of HSV infections in the neonate: disseminated infection; localized infection of the skin, eyes, and mouth (SEM); and central nervous system (CNS) infection. Localized SEM disease is the most common presentation, accounting for 45% of neonatal HSV cases. CNS disease accounts for 30% of cases, and disseminated disease occurs in 25% of cases.31 The greatest risk for HSV transmission occurs in neonates born to a mother with primary genital herpes infection near the time of delivery, with an estimated risk of about 50%. The risk for HSV transmission in neonates born to a mother with reactivation of HSV infection31,32 is less than 2%.

Skin disease can present with small 2- to 4-mm vesicles that are usually in clusters. A common site of involvement is on the scalp at the site of fetal scalp monitor electrodes. Babies may present only with systemic symptoms, including features of sepsis or seizures. In 1 study, 7% to 39% of patients did not have skin findings at the time of presentation and did not develop vesicles during their disease course.33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree