Health Care-Associated Infections in the NICU

INTRODUCTION

Health care-associated infection (HCAI), also referred to as nosocomial or hospital-acquired infection, is an infection that a patient acquires and becomes evident 48 hours or more after admission to a hospital, it was not present or incubating at the time of admission to the hospital, and develops while the patient is receiving treatment of other conditions. These infections are associated with more serious illness, prolongation of stay in a health care facility, increased long-term disability, excess deaths, and high additional financial burden on health care and patients and their families.

The HCAIs commonly encountered in the neonatal intensive unit (NICU) are as follows:

1. Bloodstream infection (BSI), primarily catheter-associated bloodstream infection (CABSI), the most common HCAI in the NICU

2. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)

3. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI)

4. Surgical site infection (SSI)

5. Ventricular shunt-associated infection

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Incidence

According to the World Health Organization, the incidence rate of HCAIs in the United States is 4.5%; prevalence in the European countries is 7.1%; and in the low- and middle-income countries it varies from 5.7% to 19.1%. The overall annual direct medical costs of HCAI to US hospitals ranges from $28.4 to $45 billion, and the benefits of prevention range from $5.7 to $31.5 billion.1 In 2002, the estimated number of HCAIs in US hospitals, adjusted to include federal facilities, was approximately 1.7 million, of that number, there were 33,269 among newborns in high-risk nurseries and 19,059 among newborns in well-baby nurseries; an estimated 98,987 deaths were associated with HCAIs.2

The Pediatric Prevention Network Study showed that of the 827 NICU patients surveyed, 11.4% had 116 hospital-acquired infections: 52.6% bloodstream, 12.9% lower respiratory tract, 8.6% ear-nose-throat, and 8.6% urinary tract infections (UTIs).3 The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) reported the highest incidence of device-associated infections (DAIs) was in neonates weighing 750 g or less.4

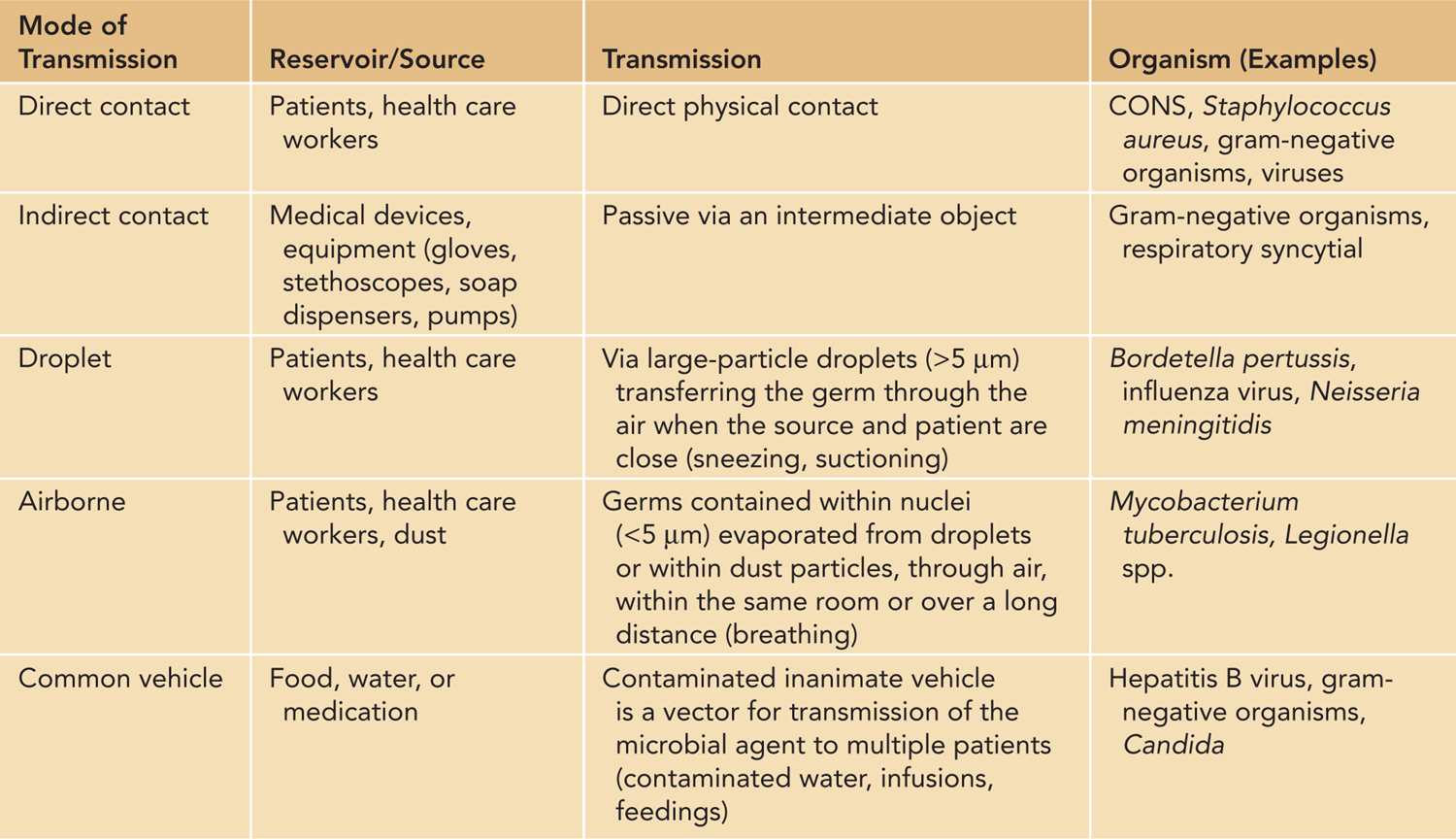

Hands are the most common vehicles to transmit health care-associated pathogens (Table 53-1). Transmission of pathogens from one patient to another via health care workers’ hands requires 5 sequential steps:

Table 53-1 Modes of Transmission Within the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

1. Germs are present on the patient’s skin and surfaces in the patient’s surroundings.

2. By direct and indirect contact, the patient’s germs contaminate health care workers’ hands.

3. Germs survive and multiply on health care workers’ hands.

4. Inadequate hand cleansing results in hands remaining contaminated.

5. Microorganisms are cross transmitted between two patients via a health care worker’s hands.

Risk factors for HCAI in the NICU are the following:

1. Patient-related factors contribute to neonatal susceptibility to bacterial infections:

• Anatomically and biochemically immature, as well as frequently compromised, skin and mucous membranes

• Reduced numbers or function of macrophages and dendritic cells in peripheral tissues (eg, lung)

• Lower numbers of neutrophils in the bone marrow

• Decreased immunoglobulin (Ig) G and complement levels, especially in premature neonates

• Inability to respond to bacterial carbohydrate antigens

• Nature of the illness requiring NICU admission

2. Use of indwelling medical devices during hospitalization:

• Intravascular catheters (UAC [umbilical artery catheter], UVC [umbilical venous catheter], PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter], PIV [peripheral intravenous] catheter, PAL [peripheral arterial line] catheter)

• Transmucosal medical devices (endotracheal tubes, oro-/nasogastric tubes, urinary catheters)

• Ventricular shunts

• Surgical drains, chest tubes

3. Use of medications, such as the following:

• Broad-spectrum antibiotics: Antibiotics use modifies developing neonatal microflora. In addition, microorganisms have natural as well as acquired mechanisms of antibiotic resistance (eg, Pseudomonas aeruginosa efflux pumps pump antibiotics out, S. marcescens amp C gene can be induced by exposure to antibiotics), with the former representing microbial adaptation to antibiotics exposure. Judicious use, including narrowing antibiotic use after sensitivity is obtained, and timely discontinuation of antibiotics are essential.

• Histamine2-receptor antagonists.5

4. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN)6

5. Severity of underlying illness

6. Overcrowding and poor staffing ratio

PATHOGENESIS

Microorganisms causing HCAI can come from the patient’s own microflora (eg, skin, nasopharynx, gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract) or from the environment/people in contact with the patient (family, visitors, health care workers). Most of the patients with bacterial or fungal HCAIs have indwelling medical devices used in their management (endotracheal tubes, intravascular lines, urinary catheters). In a study describing the epidemiology of 6290 nosocomial infections in pediatric intensive care units, BSIs, pneumonia, and UTIs were almost always associated with the use of an invasive device.7

Bloodstream Infections

Bloodstream infections are the most common HCAIs in the NICU. The highest rate of BSIs in the NICU is in the extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants. However, even at a birth weight greater than 2.5 kg, BSI is still the most common infection. BSIs can be any of the following:

• Primary BSIs: These are the majority (64%) of all BSIs, primarily CABSIs. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definitions, BSI can be

• Laboratory-confirmed infection, or

• Clinical sepsis (5% of BSIs). The CDC definition of clinical sepsis (introduced in 1986) was intended principally for infants because of its rarity in other patient groups.

• Secondary BSIs: These are related to infections at other sites (such as the urinary tract, lung, postoperative wounds, skin).

Catheter-Associated Bloodstream Infections

The majority of serious CABSIs are associated with central venous catheters (CVCs). CABSI is likely if a primary BSI develops in a patient who had a CVC within 48 hours before the development of the infection. If the time interval was longer than 48 hours since CVC placement, there must be compelling evidence that the infection was related to the vascular access device.

Potential routes for catheter contamination are the following:

1. Migration of skin organisms at the insertion site into the cutaneous catheter tract and along the surface of the catheter with colonization of the catheter tip;

2. Direct contamination of the catheter or catheter hub by contact with hands or contaminated fluids or devices;

3. Hematogenous seeding from another infection focus; or

4. Infusate contamination.

The major determinants of infection risk with intravenous catheters are:

1. Type of catheter

2. Location of catheter placement: Femoral catheterization was associated with increase in overall infection (20 vs 3.7 per 1000 catheter-days), clinical sepsis with or without documented BSI (4.5 vs 1.2/1000 catheter-days), and thrombotic complications.8

3. Duration of catheter placement: In one of the studies, the incidence rate of CABSIs increased by 14% per day during the first 18 days after PICC insertion; from days 36 through 60, the incidence rate again increased by 33% per day.9

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

Ventilator-associated pneumonia can be diagnosed in a patient who is on mechanical ventilation through an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube for at least 48 hours. Surveillance studies reported the incidence of pneumonia in the NICU was from 6.8% to 32.3% of HCAIs. The rate varied by birth weight category as well as by institution10–13 due to the definition used, the people doing surveillance, and the frequency of surveillance. CDC definitions for VAP exist for infants less than 1 year of age, but there are no specific definitions for low or very low birth weight infants. Lower respiratory tract infections mostly occur by aspiration of bacteria that colonize the oropharynx or the upper gastrointestinal tract, which is facilitated by the presence of endotracheal tubes.14–16 The aspiration can frequently be subclinical (microaspiration), and pepsin, a marker of aspiration, was detected in 91.4% of tracheal aspirates of preterm neonates.17

Biofilms

Biofilms have been found to be involved in a wide variety of microbial infections in the body. They are aggregates of microorganisms in which cells adhere to each other on a surface, frequently embedded within a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substance. These formations of microbes lead to persistent infections resistant to conventional antimicrobial treatment and can be a major cause of treatment failure. In addition, antibiotic exposure can stimulate biofilm formation. According to the National Institutes of Health, up to 80% of human bacterial infections involve biofilm-associated microorganisms. HCAIs in the NICU in which biofilms have been implicated include catheter infections, UTI, endocarditis, and infections of permanent indwelling devices such as ventricular or cardiovascular shunts and grafts. Endotracheal tubes become coated with bacterial polysaccharide biofilms containing microbial flora, and during suctioning, these bacterial aggregates are dislodged and moved to the lower airways. Bacteria frequently involved in biofilm-associated infections include the grampositive pathogens, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus species, and gram-negative organisms, such as P. aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae (eg, Escherichia coli). Frequently, biofilm-associated infections are polymicrobial, with interaction between microbes increasing persistence.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology and clinical presentation of sepsis, a clinical syndrome complicating severe infection, is addressed in detail in chapter 52.

Etiology

Overall, the leading causes of HCAIs in the NICU are coagulase-negative staphylococci (CONS). In the first 30 days after birth, other frequent pathogens are S. aureus, Enterococcus species, and gram-negative enteric bacteria; after 30 days of age, fungi, especially Candida species and Malassezia furfur, are increasingly found.

The most frequent organisms causing BSIs in the NHSN study were CONS (28%), S. aureus (19%), and Candida species (13%).10

In a study looking at VAP in extremely preterm neonates in a NICU, most of the tracheal isolates grew polymicrobial cultures; the most commonly isolated organisms were P. aeruginosa (38.4%), Enterobacter spp. (38.4%), S. aureus (23%), and Klebsiella spp. (23%).18 In the NHSN study, the most frequent pathogens in VAP were Pseudomonas species (16%), S. aureus (15%), and Klebsiella species (14%).10

The most frequent organisms causing UTIs are gram-negative enteric bacteria, and the leading pathogens are E. coli, Candida albicans, and P. aeruginosa.

Surgical site infections are most frequently caused by S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and CONS.

The major problem is that up to 50%–60% of HCAIs are caused by multiresistant organisms. In the NHSN report, of 673 S. aureus isolates with susceptibility results, 33% were methicillin resistant; the incidence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) CABSIs has decreased in recent years, perhaps as a result of prevention efforts. Gram-negative organisms have significantly increased resistance to third-generation cephalosporins (eg, Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli), as well as imipenem and ceftazidine (P. aeruginosa). Candida spp. are found to be increasingly fluconazole resistant.

Prevention

The hospital-based programs of surveillance, prevention, and control can significantly reduce the rate of HCAIs.19–21 In 2005, the NHSN succeeded and integrated previous surveillance systems at the CDC: National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS), Dialysis Surveillance Network (DSN), and National Surveillance System for Healthcare Workers (NaSH). It is estimated that at least 50% of HCAIs could be prevented.

The single most effective measure to reduce HCAIs is hand hygiene.22 Hand hygiene should be performed with antimicrobial soap and water when hands are visibly dirty or soiled with blood and other body fluids; if not visibly soiled, alcohol-based hand rub may be used for routine decontamination of hands.

The following are 5 moments for hand hygiene (World Health Organization):

1. Before touching a patient;

2. Before a clean/aseptic procedure;

3. After body fluid exposure risk;

4. After touching a patient; and

5. After touching patient surroundings.

Validated and standardized prevention strategies have been shown to reduce HCAIs.23,24 Prevention measures can be divided into the following:

1. General measures:

• Surveillance

• Standard precautions: hand hygiene, gloves, gowns, masks, and so on

• Isolation precautions: contact, droplet, and airborne

2. Measures targeted against specific infections: BSIs (Table 53-2),25 respiratory infections (Table 53-3),26 UTIs, and so on.

Table 53-2 Prevention of Catheter-Associated Bloodstream Infections