Prepubertal Genital Examination

Cindy W. Christian

Joanne M. Decker1

1Dr. Joanne M. Decker passed away in 2007 after a long battle with cancer.

Introduction

Examination of the prepubertal genitalia should be part of a complete physical examination during well-child care visits. Although the performance of this examination is not routine in an acute care setting, under certain circumstances it is essential. The purpose is either to ensure normal anatomy during routine checkups or to evaluate for pathology in children who present with complaints specific to the genital area. The examination is generally done by physicians or specially trained nurses in a variety of outpatient and inpatient settings. Until recently, the physician has paid little attention to normal and abnormal prepubertal genital anatomy, particularly in girls. Although the technique of examining young patients is relatively simple, the interpretation of findings can be difficult. This chapter discusses the approach to performing a proper genital examination in the prepubertal child, basic genital anatomy, and common abnormalities and problems encountered. Specific indications for performing the examination also are discussed. If, by history or examination, sexual abuse is suspected, Chapter 94 may be used as a reference for the proper method of collecting forensic evidence. Examination of the genitalia in the adolescent patient is reviewed in Chapter 93.

Anatomy and Physiology

Genital anatomy and physiology are largely influenced by hormonal changes throughout childhood, so individual patients have significant variation in the appearance of the genitalia, depending on age.

The normal full-term infant male should have a clearly identifiable penis with an average length of 3 to 4 cm. Any newborn boy with a penis measuring less than 2.5 cm should be referred to an endocrinologist (1). The examining physician should note if the urethral opening is in the normal position at the apex of the glans or displaced ventrally (hypospadias) or dorsally (epispadias). Infants with either of these abnormalities require urologic evaluation. In the uncircumcised newborn boy, the foreskin is rarely retractable and should not be forced. The scrotum should be fused. A bifid (partitioned) scrotum is abnormal and requires evaluation for ambiguous genitalia. Hydroceles are common in the newborn period and, in isolation, require only follow-up examinations. The testicles should be palpable in the scrotum or easily located in the distal inguinal canal. The child with a true undescended testicle should be referred to a surgeon.

Occasionally, a prepubertal boy can present with a painful, swollen penis. In the absence of a known trauma, this swelling may be due to inflammation of the glans (balanitis) or the foreskin and the glans (balanoposthitis). The inflammation

will usually resolve if treated with warm soaks and an oral antibiotic such as cephalexin. In uncircumcised boys, a painful swollen penis could be caused by an unretractable foreskin (phimosis) or a foreskin that is retracted over the glans and now cannot be reduced to the normal position (paraphimosis). Procedures for paraphimosis reduction are described in Chapter 98. The clinician should remember, however, that it is normal to be unable to retract the foreskin back from the normal position in an uncircumcised boy until he is about 3 years of age. Essentially no other changes are apparent in the male external genitalia until the onset of puberty. The first genital change to occur is the enlargement of testicular diameter to greater than 2.5 cm. The average age of onset of testicular enlargement is 11.6 years, with a standard deviation of approximately 1 year (2). A boy younger than age 9 with testicular enlargement should be referred to an endocrinologist for evaluation of precocious puberty.

will usually resolve if treated with warm soaks and an oral antibiotic such as cephalexin. In uncircumcised boys, a painful swollen penis could be caused by an unretractable foreskin (phimosis) or a foreskin that is retracted over the glans and now cannot be reduced to the normal position (paraphimosis). Procedures for paraphimosis reduction are described in Chapter 98. The clinician should remember, however, that it is normal to be unable to retract the foreskin back from the normal position in an uncircumcised boy until he is about 3 years of age. Essentially no other changes are apparent in the male external genitalia until the onset of puberty. The first genital change to occur is the enlargement of testicular diameter to greater than 2.5 cm. The average age of onset of testicular enlargement is 11.6 years, with a standard deviation of approximately 1 year (2). A boy younger than age 9 with testicular enlargement should be referred to an endocrinologist for evaluation of precocious puberty.

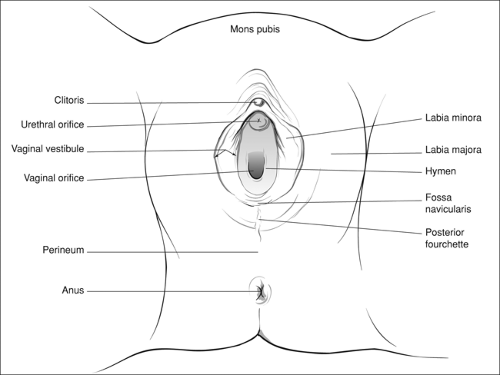

In a newborn girl, it is important to identify all normal genital structures (Fig. 91.1). In term infants, maternal estrogen causes the labia majora to appear well developed and plump. The labia generally cover the rest of the genitalia and must be separated to visualize the other structures. In preterm infants, the labia majora are thinner and separated, and may actually make the clitoral prepuce appear unusually prominent. The labia majora should never be fused posteriorly nor demonstrate rugae. Either finding would indicate ambiguous genitalia. The clitoris is located ventrally at the anterior fusion of the labia minora. If any prepubertal girl is found to have a clitoris that measures greater than 3 mm in length and 2 mm in width, she should be referred to an endocrinologist for clitoromegaly. In the supine position, the urethral meatus should be located just inferior to the clitoris, between the labia minora. The vaginal orifice is located inferior to and separate from the urethra. The hymenal membrane should be seen surrounding the entrance to the vagina, partially obscuring visualization of the vagina. It is present in all girls with otherwise normally formed genitalia. Effects of maternal estrogen on the newborn hymen cause it to appear thickened and opaque. The newborn girl may have some white or blood-tinged vaginal discharge (also secondary to maternal hormone effect), which should resolve by 2 weeks of age. Finally, the inguinal areas should contain no palpable gonads or hernias.

In the prepubertal girl, the physician should pay more attention to the anatomy of the vulva. The appearance of the

vulva changes dramatically in the first years of life, as maternal estrogen effects wane. In the prepubertal girl, the vulvar mucosa may appear quite erythematous due to the normal appearance of the vasculature in the relatively thin tissue. The labia majora are less prominent than in an adolescent or an adult, exposing the vulvar structures to some extent, which leaves these structures more vulnerable to injury from straddle-type falls. Likewise, the labia minora in the prepubertal child are thin. They meet posteriorly to form the posterior fourchette, which may exhibit some friability in young girls. This friability does not necessarily indicate pathology. Occasionally the epithelium of the labia minora is fused as a result of nonspecific irritation. Fused labia minora may impede visualization of the hymen and vagina. In most cases, this is functionally insignificant and will eventually lyse with estrogen at puberty. Some children are symptomatic, however, with urinary dribbling and secondary vulvovaginitis. These children require a short course (no more than 2 weeks) of topical estrogen, followed by a nightly application of petrolatum. Manual lysis of the adhesions is not recommended as an initial therapy.

vulva changes dramatically in the first years of life, as maternal estrogen effects wane. In the prepubertal girl, the vulvar mucosa may appear quite erythematous due to the normal appearance of the vasculature in the relatively thin tissue. The labia majora are less prominent than in an adolescent or an adult, exposing the vulvar structures to some extent, which leaves these structures more vulnerable to injury from straddle-type falls. Likewise, the labia minora in the prepubertal child are thin. They meet posteriorly to form the posterior fourchette, which may exhibit some friability in young girls. This friability does not necessarily indicate pathology. Occasionally the epithelium of the labia minora is fused as a result of nonspecific irritation. Fused labia minora may impede visualization of the hymen and vagina. In most cases, this is functionally insignificant and will eventually lyse with estrogen at puberty. Some children are symptomatic, however, with urinary dribbling and secondary vulvovaginitis. These children require a short course (no more than 2 weeks) of topical estrogen, followed by a nightly application of petrolatum. Manual lysis of the adhesions is not recommended as an initial therapy.

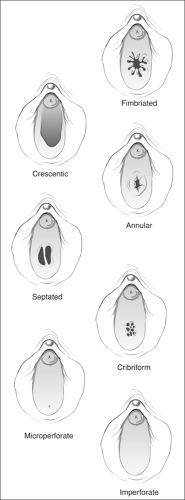

Some experts have devoted much attention in recent years to the hymenal anatomy in prepubertal children. Great variation exists in the appearance of the hymenal tissue and configuration of the hymenal orifice in young girls. Generally, the hymen is thin and may be translucent, with a lacy vascular pattern. In other children, a normal hymen may appear redundant and more opaque. Hymenal types are generally classified by both shape of the tissue and appearance of the opening (Fig. 91.2). Findings are described based on their location in relation to a clock face, with 12 o’clock at the ventral position. A crescentic hymen is probably the most common. The tissue is U shaped and appears slung between the 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock positions. Annular hymens are ring shaped, with a central orifice. A septate hymen is identified by a midline septum of tissue that creates two hymenal openings. The examiner should ensure that the septum is isolated to the hymen and does not continue internally. This can be done visually and/or with a small curved probe placed to encircle the septum if possible. A cribriform hymen contains multiple small openings and is an unusual variation. Microperforate hymens contain one small opening, which can be found anywhere on the hymenal surface. Unlike any of the discussed configurations, an imperforate hymen is abnormal and requires surgical correction.

The genitalia of prepubertal girls are susceptible to vulvovaginal irritation for several reasons. The prepubertal vagina lacks labial fat pads and pubic hair, which in the adolescent and adult serve to protect the vulva and vagina. The pH of the prepubertal vagina is neutral, providing a favorable milieu for bacterial overgrowth. Finally, prepubertal girls may not be meticulous about their hygiene, predisposing to fecal contamination of the vulvar and urethral areas. Unlike adolescent or adult patients, in whom a specific microbiologic cause of vulvovaginitis is usually identified, the majority of symptomatic prepubertal girls have nonspecific vulvovaginitis.

The anal anatomy of infants and young children is similar in both boys and girls. The anus should appear as a separate opening on the perineum, with symmetric, thin radiating rugae. Anal tags in the midline position are common and are not necessarily pathologic. In infants, small anal fissures can develop as a consequence of straining or constipation. Small, superficial anal fissures should not be confused with larger tears extending deeper into the external anal sphincter as a result of anal trauma. The anus should have a brisk wink reflex and normal tone. Children with stool in the rectal vault may exhibit anal dilation during examination. This should not be considered abnormal.

Indications

In the well-child care setting, inspection of the genitalia should routinely be done as part of the physical examination. This practice will help the child become accustomed to it as part of a normal physical examination. In addition, the physician will be able to assess for any abnormalities and become familiar with the normal variability of the prepubertal anatomy. In the acute care setting, examination of the genitalia is mandatory for any child with the following complaints: vaginal or penile discharge and/or bleeding, dysuria, genital rash, pruritus or pain, a history of genital or perineal trauma, rectal pruritus or pain, or a history of possible sexual abuse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree