Gastric Intubation

Harold K. Simon

Maia S. Rutman

William Lewander

Introduction

Gastric intubation for medical purposes dates back to Hermann Boerhaave (1668–1738), who first suggested inserting gastric tubes, and John Hunter, who reported conveying food and medicine in 1790 for a case of “paralysis of the muscles of deglutition” (1). Occasional case reports followed, but it was not until 1921, when Levin introduced the smooth catheter-tipped tube, that gastric intubation became a routine medical procedure (2,3).

Abdominal obstruction, severe trauma, drug overdose, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, among other processes, commonly require emergent gastric intubation. Gastric tubes are also utilized in patients following tracheal intubation in order to facilitate gastric decompression. The procedure is commonly performed by physicians and nurses in both the emergency department (ED) and intensive care settings. The placement of a gastric tube is straightforward but requires close attention to technique in order to avoid serious complications.

Anatomy and Physiology

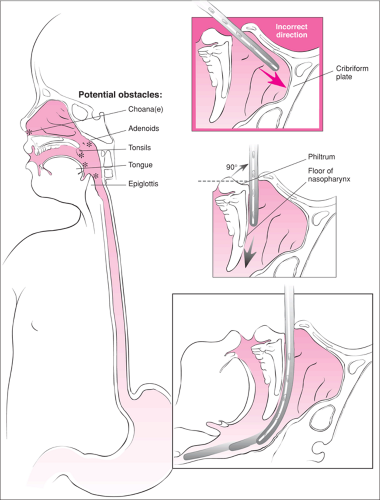

The approach to gastric intubation for children is similar to that for adult patients. Major anatomic obstacles to gastric tube placement are the nares, choanae, adenoids, tonsils, tongue, and epiglottis (Fig. 84.1). Unlike adults, however, children have increased tonsillar and adenoidal tissue size that may predispose them to traumatic bleeding during gastric intubation, especially if excessive force is used. In addition, the relative macroglossia in young children and the smaller nostril diameter may impede nasogastric intubation. Also, children are more likely than adults to have undiagnosed congenital anomalies that may act as an impediment to gastric intubation, such as choanal atresia, esophageal atresia, esophageal strictures, and tracheoesophageal fistula. Orogastric intubation may be necessary for some pediatric patients if it becomes evident that nasogastric intubation will result in excessive trauma.

The cribriform plate, an anatomic site deserving special emphasis, is a thin bone located in the superior aspect of the nasal cavity. It separates the intracranial cavity from the nasal cavity. This bone may be fractured following severe facial or head trauma, creating a point of potential access into the intracranial cavity. Placement of a nasogastric tube in the presence of such an injury has resulted in introduction of the tube into the cranial vault, an obviously catastrophic result (4). Care must therefore be taken before nasogastric intubation to ensure that a cribriform plate disruption is not present; if this cannot be assured, then orogastric intubation should be performed.

The gag reflex impedes gastric tube placement by closing the nasopharynx via the levator veli palatini and tensor veli palatini muscles (cranial nerve X) and constricting the pharyngeal musculature (cranial nerves IX and X). Impairment of the gag reflex often occurs in patients with a depressed level of consciousness. In such patients, passage of the tube may actually be easier because the patient does not struggle. However, the risk of aspiration of gastric contents into the lungs increases greatly because the tracheal protection afforded by an intact gag reflex is diminished or absent. Additionally, the gastric tube may be inadvertently passed into the trachea because the warning signs of cough or lack of phonation would not be present.

Indications

Gastric intubation is widespread in the daily practice of pediatric emergency medicine. Emergent indications include

gastrointestinal decompression (as in cases of obstruction or tracheal intubation), evaluation of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, introduction of radiographic contrast for imaging studies, administration of medications, gastric lavage, gastric decontamination of toxins, and administration of activated charcoal (see also Chapters 126 and 127). Nutritional alimentation is a common nonemergent indication for gastric intubation.

gastrointestinal decompression (as in cases of obstruction or tracheal intubation), evaluation of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, introduction of radiographic contrast for imaging studies, administration of medications, gastric lavage, gastric decontamination of toxins, and administration of activated charcoal (see also Chapters 126 and 127). Nutritional alimentation is a common nonemergent indication for gastric intubation.

Figure 84.1 Anatomy of the oropharynx with potential sites of impedance during nasogastric intubation. Note the correct path for nasogastric tube insertion and the proximity to the cribriform plate. |

Several studies have shown that rehydration via nasogastric tube is equivalent to intravenous rehydration in children with mild to moderate dehydration from vomiting and diarrhea. Phin et al. demonstrated that rapid nasogastric rehydration with Gastrolyte-R (20 mL/kg/hr for 2 hours) was as effective as intravenous rehydration with saline (20 mL/kg/hr for 2 hours) in children aged 6 months to 16 years (5). Gremse found rehydration with Rehydralyte via nasogastric tube in children aged 2 months to 2 years at a rate sufficient to replace the patient’s fluid deficit within 6 hours to be as effective as intravenous rehydration (6). Yiu et al. have contended that nasogastric tube placement is easier than placement of an intravenous catheter and that rehydration via gastric tube provides the physiologic benefits of enteral rehydration while avoiding the potential complications of intravenous therapy (7). Nasogastric rehydration has also been used successfully in children older than 4 months who have bronchiolitis without episodes of apnea or altered mental status (8).

Nasogastric Versus Orogastric Placement

Gastric intubation can be accomplished by either the nasogastric or orogastric routes. The nasogastric route allows for easier gastric tube taping and is better tolerated by the conscious patient. As mentioned previously, however, the position of the cribriform plate in the roof of the nasal cavity must be considered when placing a nasogastric tube. The possibility of inadvertent intracranial placement can occur if any cribriform disruption takes place (4,9) and has also been reported in patients with no skull injury (10). Other disadvantages of nasogastric intubation include the potential for adenoidal and tonsillar bleeding and the size limitation of the nares.

The clinician should perform orogastric intubation rather than nasogastric intubation in the settings of head or facial trauma with potential cribriform plate injury suggested by copious nasal bleeding or clear nasal secretions. Coagulopathy, epistaxis, nasal obstruction, difficult nasal passage, and small nares for the required gastric tube size are other common indications for orogastric intubation.

Blind gastric intubation should not be performed in patients with a poor gag reflex before securing an airway because of the risk of aspiration and/or passage of the tube into the trachea. Blind gastric intubation also should be avoided in patients with high-lying esophageal foreign bodies or in cases of caustic ingestions because of the risk of esophageal perforation. Of note, esophageal varices are not an absolute contraindication for gastric intubation. Blind nasogastric intubation has been shown to be safe in patients with suspected, or even proven, varices (11,12,13).

Equipment

Airway equipment (oxygen, bag-valve-mask)

Suction

Gastric tube (size appropriate to pass with minimal resistance through the nares; 16 or 18 Fr tubes routinely used in adults, 8 Fr in newborns, 12 Fr by 1 year of age) (14)

Syringe (30 to 60 mL)

Gowns (for clinician and patient), towel, gloves

Emesis basin

Nasal decongestant spray such as phenylephrine

Lidocaine jelly (2%)

Nebulized lidocaine (4%)

Surgical lubricant (water-based)

Glass of water with drinking straw

Penlight or other light source

Tongue blade

Stethoscope

pH paper

Tape

Tincture of benzoin

Rubber band and safety pin

Magill forceps

Laryngoscope

The Levin tube and the Salem sump are the two types of gastrointestinal tubes used most commonly. The Levin tube is single lumen and nonradiopaque; the Salem sump is double lumen and radiopaque. The major advantage of the double-lumen tube is that the smaller vent lumen allows for outside air to be drawn into the stomach, enabling continuous flow. The single-lumen design of the Levin tube increases the likelihood that it will become obstructed by the gastric mucosa when suction is applied. This limits the usefulness of the Levin tube in gastric decompression and lavage. By contrast, the constant flow of the double-lumen Salem sump facilitates controlled suction forces and makes the tube less likely to adhere to the gastric wall. This feature makes the Salem sump more effective for suctioning of stomach contents (11).

Procedure

The procedure should be explained to the family and the patient (when appropriate) before tube insertion. Adequate airway control must be guaranteed before attempting gastric intubation. Monitoring of the patient during the procedure should include heart rate, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry. If the patient is awake, the head of the bed should be raised so that the patient is sitting upright. If cervical spine

injury is suspected, the neck must be stabilized. The comatose patient with an intact gag reflex should be placed in a decubitus position with the head down (when cervical spine injury is not suspected) to minimize the risk of aspiration. The comatose patient with a poor or absent gag reflex should undergo endotracheal intubation before proceeding with gastric intubation (see Chapter 16). All necessary equipment should be organized, and the help of one or more assistants should be enlisted. Suction equipment and oxygen must be immediately available and operating properly. A towel should be placed over the patient’s chest, and an emesis basin in the patient’s lap.

injury is suspected, the neck must be stabilized. The comatose patient with an intact gag reflex should be placed in a decubitus position with the head down (when cervical spine injury is not suspected) to minimize the risk of aspiration. The comatose patient with a poor or absent gag reflex should undergo endotracheal intubation before proceeding with gastric intubation (see Chapter 16). All necessary equipment should be organized, and the help of one or more assistants should be enlisted. Suction equipment and oxygen must be immediately available and operating properly. A towel should be placed over the patient’s chest, and an emesis basin in the patient’s lap.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree