Ingrown Toenail Repair

Juliette Quintero-Solivan

Shari L. Platt

Introduction

Onychocryptosis, or ingrown toenail, is a common condition frequently managed in the emergency department or primary care setting. Although more common in adults, this condition is seen in adolescents and, rarely, in children (1,2,3). It principally affects the great toes, and patients often seek attention early due to the intensity of pain and its effect on ambulation (1).

An ingrown toenail occurs when the lateral edge of the nail plate impinges on the lateral skin fold and traumatizes the skin. The result is varying degrees of pain, inflammation, granulation tissue formation, and infection. Therefore, management is aimed at relieving pain, minimizing further injury, preventing recurrence, and identifying and treating infection and complications. Predisposing factors include tight-fitting shoes, trauma, trimming nails in a curved fashion, picking and tearing nail edges, and nail or digit deformities (4,5).

Anatomy and Physiology

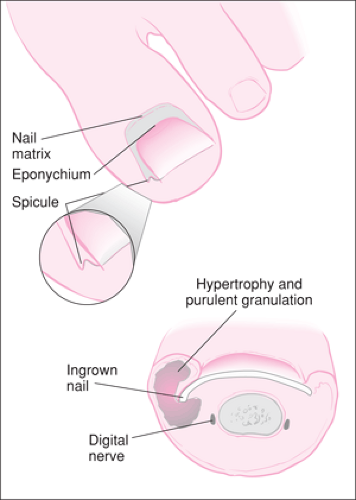

The “nail” itself, or nail plate, is a thickened convex structure made of consecutive layers of keratinized cells. The nail plate is supported by the nail unit, which is divided into four components: the nail bed, the proximal nail fold, the hyponychium, and the nail matrix (4,7). The deep nail plate layer is firmly attached to the nail bed. At the distal end of the digit, the nail bed and plate separate, and the skin thickens to become the fingertip. The junction between the free edge of the nail plate and the skin of the fingertip is the hyponychium, which forms a seal between these two layers (4). Proximally, the nail plate inserts into the proximal nail fold and is sealed dorsally by the eponychium, or cuticle. Within the proximal nail fold is found the nail germinal matrix (Fig. 117.1; see also 115.2A). The matrix extends from the distal edge of the lunula (the white crescent shape at the base of the nail) and lateral edges of the nail plate to the most proximal extent of the nail root, the nail apex (4). The nail predominantly grows distally from the germinal matrix at a rate of approximately 2 mm per month (7).

The main pathophysiology of this condition occurs when a hard nail spicule, acting like a foreign body, imbeds into the lateral skin fold and causes reactive inflammation and ultimately secondary infection. Three stages of disease have been proposed by Heifitz: stage I, mild edema and erythema along the lateral nail fold; stage II, increased pain, edema, and erythema, with evidence of drainage; stage III, chronic inflammation with marked granulation tissue formation and lateral fold hypertrophy (8).

Indications

Management of ingrown toenails ranges from nonsurgical (conservative) treatment to multiple surgical options, depending on the stage of disease, the chronicity of symptoms, the etiology, and existing comorbid conditions (7). Stage I and mild stage II lesions are best managed by conservative means (4). However, for higher grade lesions, treatment failures, and recurrences, more aggressive minor surgical procedures are employed, such as angular nail plate resection (wedge resection), partial nail resection, complete nail plate resection, wedge excision of the nail fold, plastic nail wall reduction, partial onychectomy, complete onychectomy, and Syme amputation

of the toe (4,9). Simpler surgical interventions are easily performed in the emergency department or outpatient setting, depending on practitioner comfort level and experience; however, management of more complicated lesions may require more specialized care.

of the toe (4,9). Simpler surgical interventions are easily performed in the emergency department or outpatient setting, depending on practitioner comfort level and experience; however, management of more complicated lesions may require more specialized care.

In mild cases, these interventions may be curative, but in more severe cases, these procedures are palliative and should be performed in conjunction with more permanent solutions, such as chemical or surgical matricectomy (3,4,7). The ultimate goal of all treatment is to alleviate the nail spicule impaction and prevent recurrences, which will subject the patient to multiple painful surgical procedures. Despite extensive experience and literature on management approaches, much disagreement and therefore variability exists among practitioners (6). Regardless of the management employed, all patients should be instructed on proper foot hygiene, horizontal nail trimming, and avoidance of tight-fitting shoes (10).

Equipment

Digital block anesthesia

1% or 2% lidocaine without epinephrine

Syringe with 25- or 27-gauge needle

Digital tourniquet, quarter-inch Penrose drain

Povidone-iodine or antiseptic cleanser

Sterile gauze 4″× 4″

Sterile cotton or petrolatum gauze

Isopropyl alcohol or collodion

Scalpel blade, No. 11

Nail cutter or splitter

Hemostat, small

Antibacterial ointment

Nail file, small

Suture material for wedge resection

Silver nitrate sticks

Mini-curette

Procedures

Nonsurgical Treatment

Mild to moderate lesions (minimal to moderate pain, erythema, no discharge) can be managed conservatively (4,7,9,11). This is the most frequently used management approach to stage I lesions (4). Manipulation of an exquisitely tender ingrown toenail often requires a digital nerve block (Chapter 35). Use of topical local anesthetic cream such as EMLA prior to digital nerve block for ingrown toenail surgery was not shown to provide clinical benefit in one study (12). However, many practitioners continue to use it prior to the digital nerve block until more definite data exist. Bleeding may be minimized by applying a digital tourniquet before any procedure. A mini-curette can then be used to remove any visible debris or nail spurs. If the nail is curved to form a central peak, the central portion of the nail surface may be filed down until the nail bed matrix is visible through the thinned nail, which allows for release of the curvature pressure. The affected nail edge is then grasped with a hemostat and lifted out of the nail groove by rotating away from the nail fold (Fig. 117.2). The nail plate must be handled with care to avoid fracturing it. Debris is again removed by curettage, and granulation tissue may be ablated via application of a silver nitrate stick for no longer than 1 minute. A small piece of cotton soaked in alcohol or petrolatum gauze is then firmly packed under the nail edge. The patient may replace the alcohol-soaked swab daily. Another similar approach is to pack a wisp of cotton under the nail edge and soak it with collodion. This may remain in place for 3 to 6 weeks and then should be replaced until the nail grows beyond the distal aspect of the nail fold. The patient must be instructed to follow strict foot hygiene habits consisting of warm water soaks of the affected toe, trimming of the nail transversely as it grows, and wearing of loose-fitting footwear. This procedure, with good patient compliance, is associated with a success rate as high as 96% in patients with stage I and mild stage II disease (3,13,14,15,16,17,18).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree