▪ INTRODUCTION

In the beginning of the 20th century, leading causes of infant mortality (approximately 150/1,000) included infectious diseases. With the development of antibiotics and increasingly sophisticated medical and surgical therapies, the primary causes of child mortality shifted to genetic and congenital disorders (

1). Particularly, for syndromic conditions, the pediatrician is commonly the first medical provider to raise the issue of future pregnancies and the possibilities for prenatal diagnosis.

Over the course of the past four decades, there have been revolutionary changes in our approach to prenatal diagnosis and screening (

2). In the 1960s and 1970s, we evolved from merely wishing patients “good luck” to then asking “how old are you?” Maternal age was, and still is, a cheap screening test for aneuploidy, but there has been an explosion of techniques that have dramatically enhanced the statistical performance of screening tests to identify high-risk patients. Screening for elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) for neural tube defects (NTDs) began in the 1970s, and low MSAFPs were discovered to be associated with Down syndrome (DS) and trisomy 18 in the 1980s (

3). Nuchal translucency (NT) and several other ultrasound (US) markers then emerged, which increased the efficacy of both US screening and detection of anomalies. Biochemical and now molecular markers have moved to the forefront of screening and diagnostic testing and have both revolutionized our abilities and challenged some of the basic tenets of the past decades (

2).

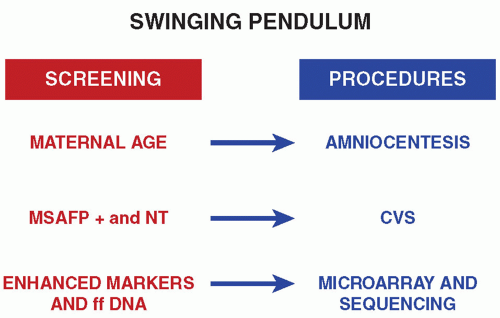

We see a pendulum swinging back and forth between screening and testing primacy as new technologies have been developed (

Fig. 10.1). Overall, prenatal diagnosis has moved along two parallel paths that sometimes converge (i.e., imaging and tissue diagnoses) (see also

Chapters 12 and

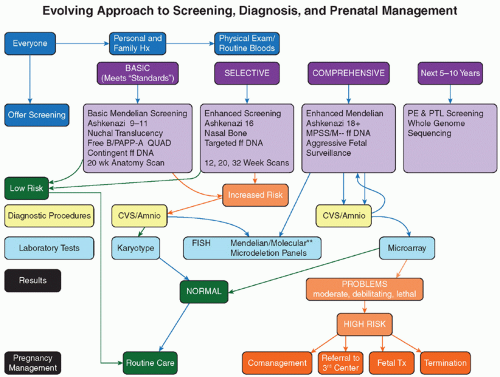

35). In many instances, clinicians are experts in one diagnostic modality or the other; there are a very limited number who are experts in both. As a result, there is often huge variability in approach to screening and diagnosis depending upon by whom and where a patient is seen. We can, oversimplistically, divide overall approaches into “basic,” “selective,” and “comprehensive.” As they internalize reproductive risks, both physicians and patients have to decide how much effort they are willing to exert to evaluate those risks and what they would do with the results (

Fig. 10.2). As with all advances in medicine and science and culture within any society, there is a gradual acceptance and incorporation of new technologies that proceed at highly different paces in different locales. The Internet has hastened the dissemination process; sophisticated patients even from remote areas can now access information on what is available if they are willing to travel to get it. At tertiary/“quaternary” centers such as ours, a significant proportion of patients travel considerable distances for services that are not available at home (

4,

5).

Thousands of papers and hundreds of textbooks have been written over the past decades about the subjects addressed in this chapter, but only a miniscule percentage of the available literature can be cited here. We will provide a summary of key points, but no short chapter can possibly do justice to the enormous technical advances in multiple disciplines that have contributed to our abilities to screen, diagnose, and treat fetal conditions. In this chapter, we concentrate on “classic” genetics, while in

Chapter 12, the focus is on US and other imaging techniques.

▪ GENETIC COUNSELING

As the complexity of genetic information has increased massively in scope and amount, the need to explain it has skyrocketed in parallel. The best analogy is to computers, for which “Moore law” predicted that capabilities would double every 18 to 24 months and cost would decrease by 50%. At least the first half of the equation has applied in genetics. The situation has been made even more challenging because currently advances in clinical medicine are often beholden to technologic advances in disciplines that are outside the “culture” of medicine (

6). For example, many of the noninvasive screening techniques rely upon the ingenuity and intellectual capabilities of electrical engineers and venture capitalists who do not necessarily adhere to the ethos of putting patient care above all else and who have pushed to introduce tests into practice without sufficient testing, medical peer review, and user/patient education. Numerous direct-toconsumer genetic companies have emerged that provide frequently alarming information—often without context. Likewise, shopping mall US “boutiques” have emerged to supply “baby pictures” (

7). In both instances, patients often believe they have received complete services when in fact important questions about their specific situation have neither been asked nor answered (

7).

Genetic counseling is the foundation of educating patients as to the risks of reproduction, opportunities to investigate those risks, and options for dealing with the information obtained. There is no one standard for what genetic counseling is in practice. Numerous studies have documented that the education of most obstetricians in genetics is suboptimal; thus, relatively few physicians caring for pregnant women are in a position to have a substantive discussion about complex genetic issues (

8). There are approximately 200 obstetrician-gynecologists in the United States who are also trained and board certified in genetics, so that the approximately 2,000 maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists perform a disproportionate proportion of genetic evaluations. However, while they often have considerably more knowledge than general obstetricians, perinatologists are commonly very time challenged and may not maintain a state-of-the-art understanding of the rapid changes

in screening and testing technology options or have the time for in-depth, unrushed discussions with patients.

Genetic counseling as a profession emerged over the past few decades. Genetic counselors are master’s trained individuals who have both an in-depth knowledge of genetic fundamentals and an understanding of screening principles and testing options. Their credo includes respect for one of the key tenets of genetics, that is, nondirective presentation of information. In many settings, the counselors have far more understanding of genetic issues than does the attending physician, which can be the cause of quality of patient care issues if care is not regarded as a team effort. The authors, all of whom have received formal training in genetics, believe that it is optimum to have a coordinated team approach to patient care. What too frequently occurs is that a “vending machine” selection of possible testing options is offered to the patient without adequate guidance. Only when there is an abnormal result does the primary medical provider call for help to explain to an often panicked patient what the results actually mean. When possible, we believe that dedicated centers providing the continuum of genetic counseling, diagnosis, and treatment are optimal. Alternatively, in this digital age, it should be possible to create a hierarchy of services from networked providers that approximates the kind of care that would be available in a comprehensive center.