Otolaryngologic Disorders

David E. Tunkel

Austin S. Rose

Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21287.

Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 07599-7070.

Pediatric otolaryngology encompasses the diagnosis and treatment of childhood head and neck disease. This expanding discipline includes the management of acquired and congenital cervicofacial masses, inflammatory and neoplastic diseases of the upper aerodigestive tract (including ears, pharynx, nose, sinuses, larynx), and communication disorders affecting hearing and speech. The broad scope of pediatric otolaryngology cannot be covered in a single chapter. Thus, more recent advances in the management of laryngotracheal disorders and inflammatory sinus disease are described comprehensively, and several other topics within pediatric otolaryngology are more briefly discussed.

PEDIATRIC LARYNGOTRACHEAL DISORDERS

Pediatric upper airway disease can be congenital or acquired. Prominent symptoms include impaired ventilation, stridor, and voice abnormalities, and even hypoxemia in severe cases. The following section details an approach to evaluating the young child with stridor.

The Evaluation of Stridor

The infant with stridor requires a systematic evaluation dictated by the severity of airway compromise. When airway obstruction is severe or rapidly progressive, the evaluation often consists of immediate endoscopy in the operating suite with stabilization of the airway. Subacute or chronic stridor without airway compromise can be evaluated with an orderly history and physical examination, airway endoscopy, and radiographic studies (1).

The etiology of stridor can be suggested by history, and attention is placed on the time of onset, the duration of stridor, and any aggravating or alleviating factors. Stridor that starts at or near the time of birth suggests the presence of a congenital laryngotracheal anomaly, such as laryngomalacia, vocal cord paralysis, congenital subglottic stenosis, or a compressive vascular ring. A history of endotracheal intubation is associated with acquired subglottic stenosis. The details of intubation, such as tube size, duration of intubation, and the reasons for intubation should be documented. Hoarseness or absent cry are symptoms of glottic lesions, such as vocal cord paralysis, laryngeal papillomatosis, or a glottic web. Low-pitched barky cough associated with stridor suggests a subglottic lesion, such as subglottic stenosis, edema, or hemangioma.

When stridor occurs suddenly in a previously asymptomatic child, foreign-body aspiration must be considered. A negative history does not rule out this possibility. Acute inflammatory laryngotracheal disease such as viral laryngotracheobronchitis (croup) or bacterial epiglottitis should also be considered.

Examination of the child with stridor involves a full head and neck evaluation, looking for head and neck masses and stigmata of craniofacial syndromes (Fig. 55-1). Stridor should be defined in regard to the portion of the respiratory cycle involved with noisy breathing. Inspiratory stridor usually suggests obstruction at or above the level of the glottis, either in the larynx or pharynx. Biphasic stridor (both inspiratory and expiratory) occurs with subglottic lesions. Expiratory stridor accompanies airway obstruction in the intrathoracic tracheobronchial tree. Changes in stridor with positioning, agitation, or feeding may suggest the type of airway lesion present. Stridor from laryngomalacia usually worsens in the crying child, particularly when supine, and such stridor usually improves with prone positioning.

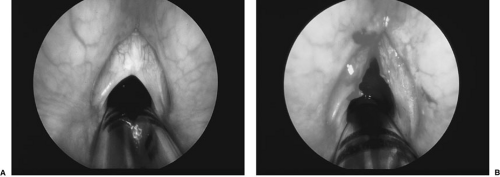

FIGURE 55-1. (A) Infant with extensive cervicofacial hemangioma. (B) Endoscopic view of larynx of same child showing extensive circumferential subglottic hemangioma. |

Examination of the larynx can be performed with indirect mirror techniques in cooperative older children, but most young children require fiberoptic laryngoscopy to visualize the dynamic larynx. This technique is performed on awake children with topical anesthesia and allows an assessment of the airway from the nasal vestibule to the glottis. The supraglottic larynx can be seen during all phases of breathing. True vocal cord anatomy and motion is documented.

Soft-tissue lateral and anteroposterior neck radiographs are useful in outlining epiglottis size, retropharyngeal profile, and subglottic and tracheal anatomy. Chest radiographs can suggest vascular ring compression of the trachea and can rule out concomitant pulmonary disease. Mediastinal masses, an uncommon but serious cause of childhood stridor, can be seen on chest radiographs. Inspiratory/expiratory and lateral decubitus chest radiographs can display air trapping suggestive of bronchial foreign-body aspiration.

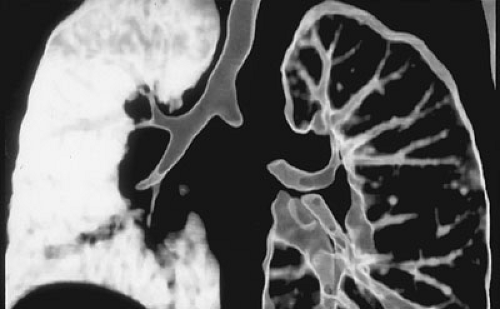

Airway fluoroscopy, usually combined with barium esophagography, can image changes in airway caliber during active respiration. A barium esophagram can be diagnostic for a compressive vascular ring. Gastroesophageal reflux or aspiration can also be detected. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging are used when a neck or chest mass that needs anatomic definition is found. Although direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy remain the gold standard, “virtual endoscopy” based on high-resolution spiral CT scanning provides a less invasive means of increasingly detailed airway evaluation (Fig. 55-2) (2).

The most definitive evaluation of static airway anatomy is obtained with direct laryngoscopy and rigid bronchoscopy performed in the operating room under general anesthesia. Rigid telescopes combined with operative microscopes, laryngoscopes, or bronchoscopes provide a magnified assessment of hypopharyngeal, laryngeal, and tracheobronchial anatomy. Direct palpation of laryngeal structures, assessment of airway diameters, biopsy of masses, and even electromyography of laryngeal muscles can be performed intraoperatively.

Some laryngeal lesions can be treated endoscopically at the time of assessment using general anesthesia. This includes drainage of laryngeal cysts, division of laryngeal

webs (Fig. 55-3), or removal of laryngeal masses, such as papilloma. The carbon dioxide (CO2) laser or conventional microlaryngeal surgical techniques are used in these cases. Table 55-1 outlines the usefulness of several radiographic and endoscopic tests for diagnosing the most common pediatric laryngeal disorders. Operative direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy are the gold standard for diagnosing fixed laryngotracheal lesions, whereas flexible awake fiberoptic laryngoscopy is more useful for dynamic processes.

webs (Fig. 55-3), or removal of laryngeal masses, such as papilloma. The carbon dioxide (CO2) laser or conventional microlaryngeal surgical techniques are used in these cases. Table 55-1 outlines the usefulness of several radiographic and endoscopic tests for diagnosing the most common pediatric laryngeal disorders. Operative direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy are the gold standard for diagnosing fixed laryngotracheal lesions, whereas flexible awake fiberoptic laryngoscopy is more useful for dynamic processes.

Differential Diagnosis of Stridor in Infants

Laryngomalacia is the most common congenital laryngeal anomaly, comprising about 60% of all laryngeal problems in neonates. Coarse, high-pitched, inspiratory stridor is caused by supraglottic obstruction from flaccid laryngeal structures. Inward prolapse of the aryepiglottic folds and arytenoids with curling of the epiglottis is seen on awake fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Additional sites of airway pathology have been found in up to 20% of infants with laryngomalacia; hence, a complete airway evaluation is advisable even after this diagnosis is made. Laryngomalacia usually resolves spontaneously by age 2 years. In some children, feeding problems, cyanosis, apnea, or failure to thrive from this condition may warrant surgical intervention. Continuous pH monitoring with simultaneous pharyngeal and esophageal probes has demonstrated an association of gastroesophageal and laryngopharyngeal reflux in children with laryngomalacia. Treatment for acid reflux may be useful in these children (3).

Vocal cord paralysis is the second most common cause of neonatal stridor. Vocal cord motion abnormalities can be either unilateral or bilateral. Bilateral paralysis is the most common cause of severe upper airway obstruction at birth. Vocal cord paralysis can be either congenital or acquired, and diagnosis is best made by observing vocal cord motion with the flexible laryngoscope in awake, spontaneously breathing children. Stridor from vocal cord paralysis is usually inspiratory or biphasic, and in unilateral paralysis, it can be accompanied by a weak, breathy cry. The inability of vocal cords to abduct leads to airway obstruction with stridor. The inability of the vocal cords to completely adduct and close the glottis can cause hoarseness and aspiration. Congenital unilateral vocal cord paralysis can be associated with intrathoracic congenital abnormalities, whereas bilateral vocal cord paralysis can be associated with central nervous system abnormalities (i.e., Arnold-Chiari malformation). Acquired vocal cord paralysis can occur following traumatic injury to the larynx and following surgical procedures to the chest or neck where the laryngeal nerve is injured.

TABLE 55-1 Usefulness of Various Diagnostic Tests for Children With Stridor. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unilateral vocal cord paralysis is usually well compensated for in children, and only conservative feeding intervention and airway monitoring are necessary. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis in infants usually causes severe respiratory compromise, and tracheotomy is usually necessary until vocal cord motion returns spontaneously or until a surgical procedure is performed to improve the glottic airway.

Subglottic stenosis is a congenital or acquired narrowing of the subglottic airway. Biphasic stridor and barky cough, often with apparent crouplike illnesses, is a common presentation. In the neonatal intensive care unit, subglottic stenosis usually presents as extubation failure. Congenital subglottic stenosis is characterized by abnormal shape and size of the cricoid cartilage and the associated soft tissues. Acquired subglottic stenosis, with subglottic scarring secondary to laryngeal injury from endotracheal intubation, is more common and usually more severe.

The diagnosis of subglottic stenosis is suggested by neck radiographs and confirmed by direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy in the operating room (Fig. 55-4). Severe cases require tracheotomy and subsequent laryngotracheal reconstruction. Moderate airway obstruction from subglottic stenosis can be relieved by endoscopic methods or anterior cricoid split. Mild cases can be observed without specific treatment because laryngeal growth may allow resolution of symptoms.

Subglottic hemangioma is an uncommon benign lesion that causes biphasic stridor, usually presenting within the first 3 to 6 months of life. Cutaneous hemangiomas are found in one-half of these infants. A submucosal mass is seen in the subglottis at direct laryngoscopy. Tracheotomy is performed for severe airway compromise. Intralesional or systemic steroids and endoscopic laser excision can play a role in management. These lesions usually regress during the second year of life. Interferon has been used to enhance hemangioma regression in severe cases (4). Open surgical excision of laryngeal hemangioma through an anterior cricotracheal incision has been advocated by some surgeons as a means of rapid surgical cure of airway obstruction from these lesions (5).

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) is the most common pediatric laryngeal tumor. Papillomas are typically confined to the larynx, but in severe cases they can extend throughout the tracheobronchial tree and pharynx. Hoarseness and stridor are common symptoms, and presentation almost always occurs before age 3 years. A maternal history of genital papilloma exists for 60% of patients with RRP. Diagnosis is made by laryngoscopy (Fig. 55-5). Laryngoscopic removal of papilloma is necessary to prevent severe airway compromise. Repeated surgery is the

rule, and periods of rapid papilloma growth are intermittent and unpredictable. A national task force on RRP has noted a mean age at diagnosis of 3.8 years, a mean duration of disease of 4.4 years, and an average number of procedures per child of more than 20 (6).

rule, and periods of rapid papilloma growth are intermittent and unpredictable. A national task force on RRP has noted a mean age at diagnosis of 3.8 years, a mean duration of disease of 4.4 years, and an average number of procedures per child of more than 20 (6).

FIGURE 55-4. Endoscopic view of near-complete combined glottic and subglottic stenosis in a 4-week-old. This child required tracheotomy to relieve airway obstruction. |

Although laser ablation using laryngoscopes and the CO2 laser has been the mainstay of treatment for RRP, rapid precise removal of papilloma has been achieved using a microsurgical debrider originally designed for arthroscopic surgery (7). Tracheotomy should be avoided because it has been associated with tracheobronchial dissemination of papilloma in RRP patients. Although medical adjuvant therapies have been used with mixed results, intralesional injection of the antiviral agent cidofovir has shown promise in more recent reports (8).

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF CHILDHOOD LARYNGOTRACHEAL DISORDERS

Laryngomalacia

Most children with laryngomalacia require no treatment, but some children experience episodic cyanosis or apnea, feeding difficulties, or failure to thrive. Although tracheotomy has been performed for airway obstruction due to laryngomalacia, epiglottoplasty techniques developed in the past decade can improve respiratory function without tracheotomy (9). Operative endoscopy is performed, and redundant supraglottic soft tissues in the region of the aryepiglottic folds are trimmed using microlaryngeal scissors or the CO2 laser. These patients have less stridor, improved feeding, and less obstruction according to postoperative sleep studies (10,11,12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree