Menorrhagia and Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding

Deborah S. Lyon

Most gynecology textbooks begin a discussion of abnormal vaginal bleeding by first carefully outlining the endocrinology of normal bleeding and then detailing various pathologic conditions that can lead to menorrhagia. In addition, most texts clearly distinguish pregnancy-related bleeding from other vaginal bleeding problems and (depending on whether it is an obstetric or a gynecologic text) concentrate on only one of those categories.

For the emergency department (ED) physician, however, the proper focus is the patient and the chief complaint. This is one of many processes in which the initial focus should be stabilization and appropriate categorization (i.e., obstetric, gynecologic, or gastrointestinal) with later emphasis on more precise diagnosis and pathology-specific therapy.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND STABILIZATION

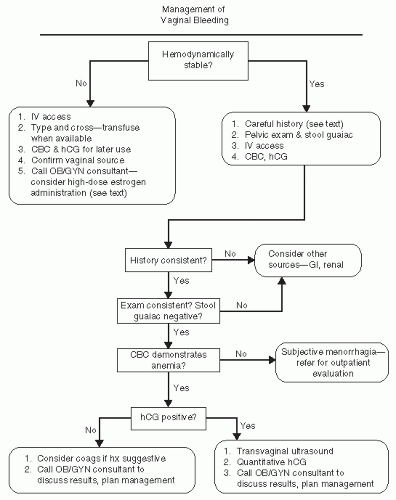

Vaginal bleeding is a common ED complaint and may represent anything from a catastrophic, life-threatening hemorrhage to a normal menstrual period in an anxious patient. An algorithm for patient assessment is presented in Fig. 21.1. To begin an assessment of the severity of the bleeding, the most helpful starting point is the patient’s vital signs. Of particular importance is the pulse rate, because many young patients demonstrate a hyperdynamic pulse well before blood pressure is affected. Some patients can tolerate remarkable anemia with relatively unchanged vital signs, but this generally occurs when bleeding is of a chronic nature. Acute bleeding episodes of hemodynamic consequence manifest themselves in vital signs before blood counts, and these should be the foundation of the initial assessment. If the vital signs point to an acute and profound process, the patient should be managed as a trauma patient, with large-bore intravenous lines, fluid resuscitation, and rapid transfusion.

The patient’s history is extremely important. Even though patients tend to exaggerate blood loss, semiquantitative evaluations such as pad counts and days of bleeding can be helpful in determining whether a vaginal bleeding episode is of clinical consequence. Of special concern is a patient whose stated history suggests less blood loss than her vital signs or her complete blood count (CBC) does; these patients may have a known problem, such as uterine leiomyomata, with a second hidden problem, such as gastrointestinal bleeding. Alternatively, the patient with an impressive history but normal vital signs may, in fact, be well compensated, and the CBC may be a better diagnostic tool.

While collecting the vaginal bleeding history, particularly if the report does not seem to accurately reflect the clinical picture, information that might elucidate other sources of bleeding should be sought. This might include gastrointestinal symptoms, hematuria, a history of liver disease or chronic illness, and a family history of blood dyscrasia.

EXAMINATION OF A PATIENT WITH VAGINAL BLEEDING

Many women are reluctant to be examined when they are actively bleeding, although in the case of an ED visit, this is less often a problem. Nonetheless, it is helpful to explain to the patient what you hope to accomplish by performing a

pelvic examination. This includes confirming the source of the bleeding, evaluating for areas of active bleeding, inspecting for anatomic abnormalities such as cervical lesions or large leiomyomata uteri, and evaluating for abdominal tenderness. In addition, a Hemoccult test should always be performed on a stool sample obtained with a fresh glove to avoid possible cross-contamination from the vagina.

pelvic examination. This includes confirming the source of the bleeding, evaluating for areas of active bleeding, inspecting for anatomic abnormalities such as cervical lesions or large leiomyomata uteri, and evaluating for abdominal tenderness. In addition, a Hemoccult test should always be performed on a stool sample obtained with a fresh glove to avoid possible cross-contamination from the vagina.

Conventional medical practice places the performance of an examination before obtaining laboratory tests. It is helpful, however, to know the results of a urine pregnancy test before examining the patient, because it may focus the physical examination on a more narrow, differential diagnosis.

A detailed examination is important. Abdominal tenderness should be noted. Even in the absence of pregnancy or trauma, intra-abdominal bleeding is possible (as in the case of a ruptured corpus luteum cyst or diverticulum). Active bleeding should be recorded, as should a quantification of the amount of blood in the vault. Point sources of bleeding should be sought. The cervix should be carefully inspected

for lesions as well as possible extruding products of conception. A bimanual pelvic examination should make a faithful attempt to identify the uterine size, recognizing that operator inexperience and patient body habitus may limit the utility of this step. Examiners who are not comfortable with the convention of sizing in comparison to weeks of pregnancy may use fruit (orange, grapefruit, honeydew, and watermelon) or sports equipment (golf ball, tennis ball, baseball, and basketball) to describe findings. Adnexal masses should be sought; although if ectopic pregnancy is on the differential diagnosis list, a vigorous adnexal examination is discouraged. Finally, a thorough rectal examination should be performed, with at tention to palpable lesions, as well as Hemoccult testing.

for lesions as well as possible extruding products of conception. A bimanual pelvic examination should make a faithful attempt to identify the uterine size, recognizing that operator inexperience and patient body habitus may limit the utility of this step. Examiners who are not comfortable with the convention of sizing in comparison to weeks of pregnancy may use fruit (orange, grapefruit, honeydew, and watermelon) or sports equipment (golf ball, tennis ball, baseball, and basketball) to describe findings. Adnexal masses should be sought; although if ectopic pregnancy is on the differential diagnosis list, a vigorous adnexal examination is discouraged. Finally, a thorough rectal examination should be performed, with at tention to palpable lesions, as well as Hemoccult testing.

ANCILLARY TESTING TO EVALUATE VAGINAL BLEEDING

Two laboratory tests are critical in the evaluation and management of vaginal bleeding: a CBC and a qualitative human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) measurement. A quantitative hCG test is not necessary to establish the diagnosis of pregnancy, because most commercial qualitative kits are sensitive to 25 IU. Most ectopic pregnancies do not become symptomatic until the hCG level reaches four-digit numbers, so a negative qualitative hCG makes ectopic pregnancy unlikely. Little diagnostic refinement and much delay result from conducting a quantitative test. There is a place for the quantitative test but not in the initial evaluation.

The CBC is useful in differentiating patients who are hemodynamically compromised from those who are well but concerned. Experienced gynecologists may be surprised when, in the course of an outpatient evaluation of vaginal bleeding, they encounter a hemoglobin of 5 or 6. These numbers occur in patients whose menorrhagia is long-standing and who are relatively well compensated but, nevertheless, require prompt therapy. By the same token, it is common for a woman to be seen in the ED with menorrhagia as her chief complaint, yet her hemoglobin is 12 or 13. In the event of an impressively acute history and an examination compatible with profound acute loss, this hemoglobin may be thought of as spurious, because blood loss takes time to be reflected in the blood count. If the history and examination are less impressive, however, the patient may be assumed to be stable. It is important in this setting to validate the patient’s concern, which may be legitimate in light of her past experience, while still providing her the reassurance she needs to pursue a more problem-specific outpatient evaluation.

The hCG serves a much more direct purpose. As mentioned earlier, many texts consider vaginal bleeding exclusively within the context of a positive or a negative hCG. A positive hCG demands a relatively immediate diagnosis, because therapy may be immediately necessary and will be tailored to the diagnosis.

If the hCG is positive for pregnancy, the likelihood is that either the pregnancy is intrauterine and threatening to abort or it is ectopically located. Physical examination may make this distinction, because incomplete spontaneous abortions often are seen with an open os and with tissue extruding. If physical examination is unrevealing, the next step in the workup is to identify the gestational age with reasonable assurance. This can sometimes be accomplished if the patient can confidently establish the date of her last menstrual period; often, laboratory testing is required. It is in this setting that a quantitative hCG is useful. Although not an accurate measure of gestational age per se, this test provides information regarding the quantity of hormone being produced, which is an indirect measure of fetal age as well as viability. The primary value of this test in the acute setting is in the context of the discriminatory zone. This is a level above which a pregnancy, if intrauterine, can confidently be

expected to be of such mass and development that it will be apparent on ultrasound. For most institutions with transvaginal ultrasound capability, this number ranges from 1,500 to 2,500 IU (see Chapter 3). If the facility has only transabdominal ultrasound capability, the range jumps to approximately 6,500 IU, and many ectopic pregnancies will have already ruptured by that level. Thus, the ability to detect ectopic pregnancies early and to manage them optimally is dependent on the presence of both quantitative hCG and transvaginal ultrasound capability.

expected to be of such mass and development that it will be apparent on ultrasound. For most institutions with transvaginal ultrasound capability, this number ranges from 1,500 to 2,500 IU (see Chapter 3). If the facility has only transabdominal ultrasound capability, the range jumps to approximately 6,500 IU, and many ectopic pregnancies will have already ruptured by that level. Thus, the ability to detect ectopic pregnancies early and to manage them optimally is dependent on the presence of both quantitative hCG and transvaginal ultrasound capability.

A full bladder is not required for a transvaginal probe scan. This is helpful, because many patients find it difficult to fill their bladders sufficiently to form a good acoustic window for a first-trimester scan. However, when necessary, the bladder can be filled by administering intravenous fluids or placing a transurethral catheter that fills it retrograde.

Having emphasized the importance of technology in discriminating between intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies, it should be repeated that this distinction can often be made on clinical grounds alone. Thus, the physical examination should always precede the ordering of a quantitative hCG or transvaginal probe ultrasound.

MANAGEMENT OF VAGINAL BLEEDING WITH A POSITIVE PREGNANCY TEST

Pregnancies with a quantitative hCG below the discriminatory zone must be evaluated strictly on clinical criteria. Certainly, an acute abdomen or a hemodynamically significant bleed must be addressed. On the other hand, a less significant bleed may be managed by observation and repeat quantitative hCG testing in 48 to 72 hours. This follow-up is best done by on obstetric care provider, and transfer of care may be arranged by telephone from the ED. It is important from a liability perspective that the ED provider documents explaining the differential diagnosis to the patient, along with the importance of keeping follow-up evaluation appointments. If the patient is stable, management of ectopic pregnancy may be conservative (methotrexate): otherwise, management should be surgical. Management of a spontaneous abortion may include dilation and curettage versus expectant management with close follow-up (Chapters 3 and 8).

MANAGEMENT OF VAGINAL BLEEDING WITH A NEGATIVE PREGNANCY TEST

If the pregnancy test is negative, follow-up is determined by the patient’s clinical condition. In terms of additional testing, a coagulation profile may be considered if the patient has a history or stigmata of liver disease, has a family history of blood dyscrasia, or is an adolescent just beginning menstruation (a time when many bleeding disorders are diagnosed). It is probably not cost effective in other settings. A patient with profound hemodynamic changes, a very low hemoglobin, or brisk bleeding is best managed by admission, whereas a less acute blood loss may easily be managed by prompt outpatient evaluation.

Acute bleeding in the nonpregnant patient is managed by liberal use of intravenous fluid replacement and blood products. Products other than packed red cells should be reserved for use in accordance with institutional protocols rather than by a preset formula. Appropriate indications for replacement of platelets or cryoprecipitate might be a diagnosed dyscrasia, need for immediate surgery, or ongoing bleeding not responding to other medical management (listed below).

There have been many proposed interventions to stop uterine bleeding in the nonpregnant patient. The most common of these is high-dose estrogen,

either intravenously or orally (1,2,3

either intravenously or orally (1,2,3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree