Maternal Obesity: Effects on Pregnancy

Amy H. Picklesimer

Karen Dorman

The recognition of obesity as a major public health issue has only emerged in the past two decades, although overweight status and obesity have long been known to be significant causes of chronic disease. Some of the most common obesity-related health complications are hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea and related respiratory disorders, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease and stroke. Esophageal, colon, hepatic, renal, pancreatic, and endometrial cancers are more common in obese individuals who also, when compared with normal weight subjects are at a higher risk of death from cancer.1,2,3 Women who are overweight or obese during their childbearing years are, therefore, at increased risk for pregnancy related complications and present management challenges for perinatal clinicians. This chapter focuses on the specific combination of obesity and pregnancy and delineates separate discussions of potential effects on the mother, fetus, and newborn.

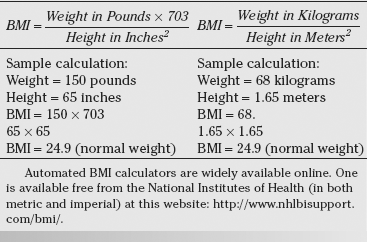

Standard measurements for relating individual body weight to height are the basis for determining body mass index (BMI) which is calculated utilizing the standard formulas depicted in Table 22-1. This creates an objective measure of weight, scaled according to height, and is commonly used to categorize individuals into underweight (BMI <18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9), and obese (BMI ≥30). Additionally, obese individuals are further subcategorized into Class I (BMI 30 to 34.9), Class II (BMI 35 to 39.9), and Class III or severe obesity (BMI greater than 40) (Table 22-2).4 These categories are applied universally to adult men and women. Children and teenagers younger than age 20 are classified by a separate set of standards that are specific for both age and gender. Although BMI does not account for differences in body muscle mass, it provides a reasonably good approximation of population-level measures of fitness and has been used by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for this purpose.

The prevalence of obesity in the United States for adults of both sexes aged 20 to 74 years in 1962 was 13.4%. By 1994, the rate of obesity had more than doubled to 23.3%. This rate continues to increase, and was measured at 32.2% in the year 2004.5,6 Not surprisingly, the obstetric population has seen an increase in the prevalence of obesity that parallels that seen in the general population. Data from 495,051 women in Utah documented the increase in rates of prepregnancy obesity (based on self-reported prepregnancy weights) from 25.1% in 1991 to 35.2% in 2001.7 These rates are similar to the rates of 51.7% for overweight, 21.9% for obesity and 8.0% for extreme obesity found in a national survey of reproductive age women (age 20 to 39) in 2004.5,8,9,10,11

Antepartum Complications of Obesity During Pregnancy

Several of the adverse health outcomes that affect nonpregnant obese individuals, like coronary artery disease or colon cancer, develop slowly and are more commonly seen outside of the reproductive years. Others, like hypertension and diabetes, are commonly seen in overweight or obese women who are of reproductive age. This population of women, as well as their fetuses and newborns, is at greater risk for medical and obstetric complications during and after pregnancy.

Maternal Complications

Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy include a spectrum that ranges from gestational hypertension, characterized by transient mild elevations in blood pressure, to preeclampsia and eclampsia, which are characterized by elevation of blood pressure and renal, hepatic and central nervous system end-organ involvement. See Chapter 7 for a complete discussion of hypertension in pregnancy.

Table 22.1 Calculation of Body Mass Index (BMI) | |

|---|---|

|

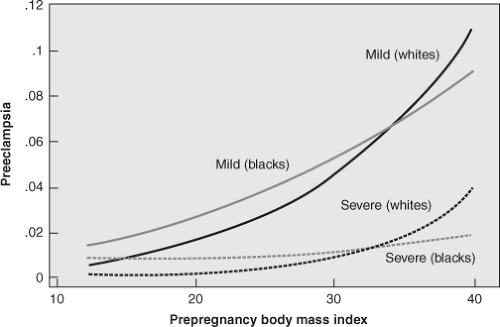

Multiple studies have documented an increased risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in obese women. Bodnar and colleagues reported on a cohort of 38,188 pregnant women, 19% of whom were overweight or obese, in which they found a strong relationship between increasing prepregnancy BMI and increasing risk for both mild and severe preeclampsia (Figure 22-1). These authors found a twofold increase in risk for mild or severe preeclampsia for overweight women (BMI 25.0–25.9), approximately a threefold increase for obese women (BMI 30.0–34.9), and a fivefold increase in the risk for preeclampsia for severely obese women (BMI 35.0–39.9).12 Similar findings were reported by Callaway and associates in a cohort of 11,252 Australian women, 34% of whom were overweight or obese, as well as by Cedergren and associates in a cohort of 621,221 Swedish women, 14% of whom were obese.11,13

Table 22.2 Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Obese gravidas are not only at higher risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, but also are more likely to begin pregnancy with a known diagnosis of chronic hypertension. It is well established that increasing BMI is strongly associated with an increased incidence of hypertension. Evidence from the Framingham Heart Study, a prospective population-based cohort study, demonstrated that hypertension and coronary artery disease were more common in obese and overweight individuals at all ages. Relative risk for hypertension in overweight adults was found to be 1.5 to 1.7, and 2.2 to 2.6 for obese adults, respectively. Additionally, population-attributable risk estimates from this cohort found that obesity or overweight status accounted for 34% of the risk in men and 62% in women.14 The prevalence of chronic hypertension in the United States among all adults aged 18 to 39 years has been estimated at 7.2%, although almost half of hypertensive patients in this age group are not aware of

their diagnosis and fewer than one third are adequately treated for their disease.15

their diagnosis and fewer than one third are adequately treated for their disease.15

Management of the obese gravida is complicated by both the increased incidence of pre-existing hypertensive disease as well as the increased risk for development of hypertensive diseases of pregnancy. It is important to establish baseline blood pressure values in early pregnancy, and care should be taken to use properly sized blood pressure cuffs in order to ensure accurate measurements.16 Additionally, evaluation of end-organ effects of hypertensive disease, such as heart failure or nephropathy, should be considered. Comprehensive evaluation of cardiac function may require electrocardiographic or echocardiographic testing. Renal function is commonly assessed by a 24-hour urine evaluation to measure total protein excretion. Establishing these parameters early in pregnancy will not only allow for optimal medical management during gestation, but also expedites identification of developing signs and symptoms of pregnancy-induced hypertensive disease and preeclampsia later in the pregnancy. Further discussion of blood pressure measurement and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy is found in Chapter 7.

Diabetes Mellitus

The second trimester of pregnancy is a physiologic state of insulin resistance. Hormones produced by the placenta lead to mild levels of maternal hyperglycemia in order to promote adequate fetal growth and development. Most gravidas adapt readily to this event. In some women, however, pancreatic insulin secretion is not adequate to counter the diabetogenic hormones. Women who have normal serum glucose levels prior to pregnancy demonstrate abnormally high postprandial and fasting serum glucose levels during pregnancy. This transient disease process is known as gestational diabetes. Although this condition resolves after delivery, untreated hyperglycemia in pregnancy is associated with a number of adverse maternal, fetal, and/or neonatal outcomes. These include: preeclampsia, disordered fetal growth, neonatal metabolic complications such as hyperbilirubinemia and hyperglycemia, and even fetal death.

The metabolic pathways in the development of obesity are complex, but adipocytes participate in several important signaling pathways that influence insulin sensitivity in the peripheral tissues.17 As a result, obese women are at increased risk for developing gestational diabetes. Sebire and colleagues reported a retrospective study of 287,213 British women in which they found the relative risk of developing gestational diabetes in obese women (prepregnancy BMI 25 to 30) to be 1.68 (99% confidence interval [CI] 1.53 to 1.84) and severely obese women (prepregnancy BMI greater than 30) to be 3.6 (99% CI 3.25 to 3.98).18 These findings were confirmed in a separate retrospective study of 1,644 American women by Rudra and associates, in which obese women (BMI greater than 29) demonstrated a relative risk for developing gestational diabetes of 4.53 (95% CI 1.25 to 16.43). Additionally, these authors found that weight gain between the age of 18 years and the study pregnancy of greater than or equal to 10 kilograms conferred a relative risk of 3.43 (95% CI 1.60 to 7.37) when compared with women who had less than a 3-kilogram weight change over the same period.19

Obese gravidas are not only at higher risk for developing gestational diabetes, but also are more likely to begin pregnancy with a known diagnosis of pre-existing Type II diabetes. Evidence from the Nurses’ Health Study, a prospective population-based cohort study of 43,581 women, demonstrated a linear relationship between increasing BMI and increasing incidence of diabetes. Even after adjusting for family history, levels of exercise, and dietary habits, the relative risk of future development of type II diabetes was 11.2 for women in the top tenth percentile of BMI when compared with women in the lowest tenth percentile.20 In a prospective study by Rode and colleagues of 8,092 Danish women, the relative risk for a diagnosis of diabetes during pregnancy for overweight women (prepregnancy BMI 25 to 30) was found to be 3.4 (95% CI 1.7 to 6.8) and for severely obese women (prepregnancy BMI greater than 30) was found to be 15.3 (95% CI 8.2 to 28.6) when compared with normal weight women.21

Management of the obese gravida includes consideration of early screening for diabetes, rather than waiting for the traditional screening window for gestational diabetes of 24 to 28 weeks. A large number of obese women may in fact have undiagnosed Type II diabetes, which is manifest by abnormal glucose tolerance testing prior to 20 weeks of gestation. For obese women who develop gestational diabetes, promoting tight control of blood glucose values optimizes both maternal and fetal outcomes. The most successful management approaches are multidisciplinary and include physicians, nurse-educators, and dietitians. By strict adherence to diet, the incidence of fetal growth disorders, stillbirth, and maternal complications such as preeclampsia can be minimized. (Further discussion on diabetes in pregnancy can be found in Chapter 10.)

Nutrition and Weight Gain

Pregnancy is a period of rapid weight gain. Increases in blood volume, enlargement of the breasts and uterus, expansion of fat stores, as well as the weight of the fetus, placenta, and amniotic fluid all contribute to total weight gain during pregnancy. Current recommendations for weight gains in pregnancy are based on a report originally published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 1990 and updated in 2009. These guidelines have been adopted by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). These recommendations

are based on observational studies of prepregnancy weight, pregnancy weight gain, and birth outcomes. Using these data, the IOM categorized women by prepregnancy BMI with a different target weight gain for each category. (Table 22-3)22 The 2009 updated recommendations also include an optimal rate of weight gain for each category of maternal BMI, which allows greater flexibility for counseling of patients who are already in their second or third trimester.

are based on observational studies of prepregnancy weight, pregnancy weight gain, and birth outcomes. Using these data, the IOM categorized women by prepregnancy BMI with a different target weight gain for each category. (Table 22-3)22 The 2009 updated recommendations also include an optimal rate of weight gain for each category of maternal BMI, which allows greater flexibility for counseling of patients who are already in their second or third trimester.

Table 22.3 Recommended Gestational Weight Gain Based on Prepregnancy Body Mass Index (BMI) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In a survey of 1,198 pregnant women, Stotland and associates found that those with a high prepregnancy BMI were more than four times as likely to report target gains above IOM guidelines.23 A similar study of more than 7,000 pregnant women by Abrams and colleagues found that weight gains above the IOM recommendations were observed for 23% of the underweight women, 49% of the normal weight women, 70% of the overweight women, and 57% of the obese women.24,25 Many women cite pregnancy as a cause of their obesity, which contributes to the widely held belief that childbearing leads to overweight status and obesity.26,27 While several studies have found the average postpartum weight retention one year after delivery of approximately 0.5 kilograms, there is a wide variation in weight retention between individual women.28,29 In a large Swedish study of 1,423 women using self-reported prepregnancy weights, 30% weighed less one year after delivery than they did before pregnancy, 56% gained 0 to 5 kilograms over the same time period, and 14% gained more than 5 kilograms.29 Risk factors for postpartum weight retention in this study were excessive pregnancy weight gain, high prepregnancy BMI, and maternal age greater than 36 years.

From these data, it appears that overweight and obese women are at increased risk for excessive pregnancy weight gain and elevated postpartum weight retention. While pregnancy is not the ideal time for weight loss, adherence to a healthy diet will allow women to optimize pregnancy outcomes and decrease the risk for excessive weight gain. These goals can be achieved by providing specific weight gain goals in conjunction with nutritional guidance as necessary.

Fetal Complications

Macrosomia

Large for gestational age and fetal macrosomia are separate but overlapping descriptions of accelerated fetal growth that are associated with shoulder dystocia, birth trauma, and/or Cesarean delivery. Based on data from the National Center for Health Statistics, ACOG recommends using the term large for gestational age to describe an infant with a birth weight equal to or greater than the 90th percentile for any given gestational age. Their recommendation for the term fetal macrosomia, on the other hand, is that it should be reserved for those infants weighing more than 4,000 or 4,500 grams at birth.30

Factors that may predispose to fetal macrosomia include: pregestational or gestational diabetes, prepregnancy maternal obesity or overweight status, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, multiparity, male fetus, as well as constitutional factors such as ethnicity, maternal birth weight, and maternal height.8,18,31,32 Many of these predisposing factors may coexist within a single pregnancy, confounding understanding of the relative importance of each factor. It appears, however, that increasing maternal weight is an independent variable for a macrosomic or large for gestational age infant. Cedergren and colleagues, in a study of more than

15,000 pregnant women with normal glucose tolerance testing, described odds ratios for large for gestational age infants to be increased for women with a BMI 29.1 to 35 OR 2.20 (95% CI 2.14 to 2.26), a BMI 35.1 to 40 OR 3.11 (95% CI 2.96 to 3.27), and women with a BMI greater than 40 OR 3.82 (3.56 to 4.16).13

15,000 pregnant women with normal glucose tolerance testing, described odds ratios for large for gestational age infants to be increased for women with a BMI 29.1 to 35 OR 2.20 (95% CI 2.14 to 2.26), a BMI 35.1 to 40 OR 3.11 (95% CI 2.96 to 3.27), and women with a BMI greater than 40 OR 3.82 (3.56 to 4.16).13

Congenital Anomalies

Population-based estimates for congenital anomalies, which include malformations, deformations, and chromosome anomalies present at birth, vary by organ system, but the overall incidence ranges from 2% to 4% of all pregnancies. The most common anomalies are neural tube defects, congenital cardiac malformations, orofacial clefts, and Trisomy 21, also known as Down syndrome.33 These and other anomalies are one of the leading causes of infant mortality in the United States, and are indirectly or directly responsible for 21% of neonatal deaths and 18% of post-neonatal infant deaths.34

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree