Management of Priapism

James F. Parker

Introduction

Priapism is defined as a sustained, unwanted, painful erection that continues hours beyond or is unrelated to sexual stimulation. It is characterized by a soft glans penis and spongy urethra in the presence of two erect corpora cavernosa.

Priapism is a relatively uncommon complaint presenting to the emergency department (ED). While the incidence of priapism in the general male population is reported as 1.5 episodes per 100,000 person years, children with sickle cell disease have an incidence in the range of 6% to 27% (1).

Priapism is a true urologic emergency that requires urgent intervention to avoid irreversible ischemic penile injury, scarring, and impotence. Numerous modes of therapy have been utilized in the treatment of priapism, with variable success. However, these therapies are not predictably effective at relieving priapism and may delay procedures that allow reperfusion of the corpora cavernosa.

Anatomy and Physiology

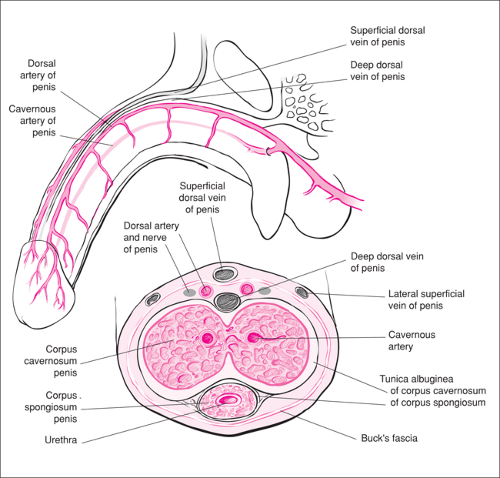

The anatomy of the penis is shown in Figure 97.1. The penis consists of the two lateral corpora cavernosa, each with a centrally located deep artery and surrounded by the tunica albuginea. Located within the ventral aspect of the penis is the urethra, which is surrounded by the corpus spongiosum. These structures are enclosed within the Buck fascia, a septum of which also separates the corpus spongiosum from the corpora cavernosa. Of particular importance in the discussion of the treatment of priapism are the structures located in the dorsal aspect of the penis. The subcutaneous dorsal vein and the deep dorsal vein course along the midline of the penis. Immediately lateral to the deep dorsal vein are the dorsal artery and the dorsal nerve, structures that must be avoided when attempting aspiration of the penis during priapism. Finally, one must be aware of the lateral superficial veins of the penis, which are depicted in the illustration in approximately the 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock positions.

Physiologically, priapism is engorgement of the corpora cavernosa, resulting in dorsal penile erection with a relatively flaccid ventral penis and glans (Fig. 97.2). This engorgement may be the result of many factors, depending on the etiology of the priapism. Perhaps the most common etiology in the pediatric population is sickle cell disease, which accounts for 28% of all cases. Up to 64% of male patients with sickle cell disease will develop priapism at some point in their lives (2). Additional hematologic causes of priapism include anemia, leukemia, and multiple myeloma.

Other sources of priapism include pharmacologic agents (antihypertensives, psychotropic medications, hormones, etc.), illicit drug use (cocaine, marijuana), trauma, infectious agents (rabies, malaria), neurologic causes (cerebrovascular accidents, spinal stenosis), bladder tumors, black widow spider envenomation, and carbon monoxide poisoning (3).

Priapism can be classified into two types: low flow and high flow. The distinguishing characteristic between these two types is whether there is too much inflow of blood to the corpora or not enough outflow of blood from the corpora. Low-flow priapism (also referred to as “ischemic priapism” and “veno-occlusive priapism”) is caused by little or no cavernous blood flow, resulting in the accumulation of hypoxic, hypercarbic blood. In this form of priapism, the corpora are rigid and tender to palpation. High-flow priapism is usually the result of trauma that causes unregulated inflow of arterial blood into the corpora. This results in corpora that are not fully rigid and are usually not painful (4). The best ways to distinguish between these two types are to use color duplex ultrasound and to measure blood gases from the corpora (2).