Management of Finger Injuries

Peter M. Antevy

Richard A. Saladino

Introduction

Finger injuries occur frequently in children and may have significant functional or cosmetic morbidity associated with them. These injuries are often treated in an outpatient setting but are usually painful and almost always frightening to the child. For all such injuries, age-appropriate restraint may be necessary and should be considered for young or uncooperative patients. This chapter discusses the outpatient management of common finger injuries, including subungual hematomas, subungual foreign bodies, nail bed lacerations and avulsions, and the mallet finger deformity.

ANATOMY

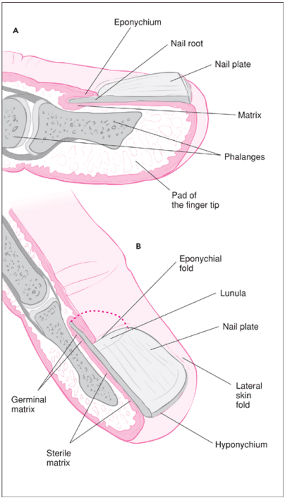

An understanding of the anatomy of the nail bed allows the clinician to appropriately plan treatment and/or repair injuries to the fingertip. The nail bed is a thin layer of epithelial tissue overlying the cortex of the distal phalanx (Fig. 103.1). The germinal matrix is the proximal element of the nail bed responsible for most of the nail formation (1). The distal end of the germinal matrix is marked by the lunula, the light semicircular area extending just distal to the eponychium. The eponychium is the fold of skin that covers the proximal nail. The sterile matrix is the distal tissue of the nail bed and is responsible for a small amount of nail growth. The nail is tightly adherent to the sterile matrix but loosely held to the germinal matrix. The lateral margins of the nail are held in place by the lateral skin folds of the fingertip.

Managing the injuries discussed in this chapter also requires knowledge of the motor and neurovascular anatomy of the finger. Extension of the finger is provided by the extensor tendon that inserts onto the epiphysis of the distal phalanx. Flexion of the fingertip occurs via the insertion of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon distal to the epiphyseal plate of the volar aspect of the distal phalanx. The flexor digitorum superficialis tendon divides and inserts on the bodies of the middle phalanges of the second through the fifth digits. A rich blood supply is afforded the fingertip by numerous branches of the ulnar and radial elements of the digital arteries. The pad of the fingertip is composed of fatty and soft tissues with dense sensory innervation.

Examination of the Digits

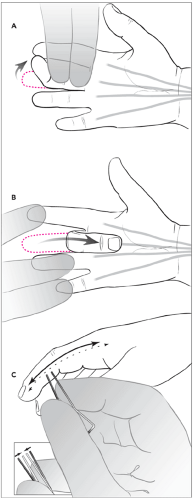

It is important to perform (and document) a thorough examination of the injured finger in order to plan appropriate treatment (Fig. 103.2). In most cases, once the sensory examination and the parts of the functional examination that require intact sensation have been performed, appropriate local anesthesia (see Chapter 35) and, if necessary, sedation (see Chapter 33) can be administered. Judicious use of sedation and local anesthesia will result in a more comfortable examination and will increase the likelihood that a child will cooperate with the remainder of the examination. The examination is focused on evaluation of motor function and neurovascular integrity. In particular, it is important to examine the fingers and hand both in the anatomic position and in the position of injury. Injured structures underlying a laceration, such as a tendon or joint capsule, may not be visible in the anatomic position but may move into the site of the laceration when the finger is placed in the position of injury.

Motor function of the fingers is assessed by testing both muscle strength and tendon function. With a cooperative child, the child is asked to place his or her hand on the examination table with the palm facing upward. The clinician then places two fingers on the involved finger just proximal to the distal interphalangeal joint, holding the finger firmly

against the table (Fig. 103.2A). The patient is then asked to flex the tip of the finger. If function is normal, the maneuver is repeated against resistance. In this way, both distal muscle strength and integrity of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon are assessed. Proximal muscle strength and integrity of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon are then tested by holding the child’s noninjured fingers against the examination table and again asking the child to flex the injured finger, first passively, then against resistance (Fig. 103.2B). Pain associated with these maneuvers in the presence of a laceration on the palmar or lateral portion of the finger may indicate a tendon injury. In younger children who are less likely to cooperate,

merely holding the child’s hand against the examination table may cause the child to flex the appropriate fingers. It may, however, be impossible to know whether associated pain is present. Consequently, lacerations of the palmar or lateral aspects of the fingers of young or uncooperative children must be thoroughly explored. Extensor tendon injuries do not require immediate repair in many cases, but a careful exam should be performed nonetheless to detect these injuries. Cooperative children are asked to close and open their hand or to curl and uncurl the affected finger. Pain or weakness with this maneuver raises the suspicion of extensor tendon injury.

against the table (Fig. 103.2A). The patient is then asked to flex the tip of the finger. If function is normal, the maneuver is repeated against resistance. In this way, both distal muscle strength and integrity of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon are assessed. Proximal muscle strength and integrity of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon are then tested by holding the child’s noninjured fingers against the examination table and again asking the child to flex the injured finger, first passively, then against resistance (Fig. 103.2B). Pain associated with these maneuvers in the presence of a laceration on the palmar or lateral portion of the finger may indicate a tendon injury. In younger children who are less likely to cooperate,

merely holding the child’s hand against the examination table may cause the child to flex the appropriate fingers. It may, however, be impossible to know whether associated pain is present. Consequently, lacerations of the palmar or lateral aspects of the fingers of young or uncooperative children must be thoroughly explored. Extensor tendon injuries do not require immediate repair in many cases, but a careful exam should be performed nonetheless to detect these injuries. Cooperative children are asked to close and open their hand or to curl and uncurl the affected finger. Pain or weakness with this maneuver raises the suspicion of extensor tendon injury.

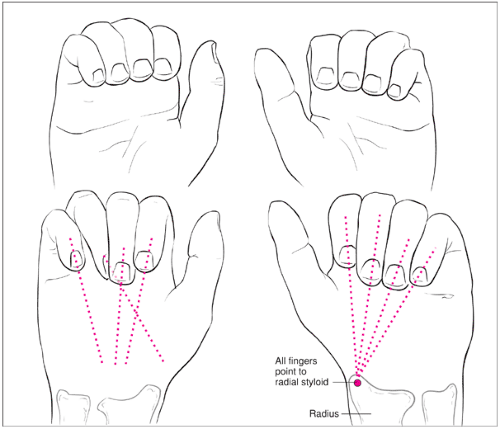

Injuries to the fingers commonly result in phalangeal fractures. Midshaft phalangeal fractures should be evaluated thoroughly for rotational deformity, angulation, or displacement and these findings clearly documented. To assess for rotational deformity, the patient is asked to slowly make a fist with the palm facing upward. As the fingertips approach the palm, they should all point toward the radial styloid. If the tip of the fractured finger points elsewhere, then a rotational abnormality is present (Fig. 103.3). Midshaft phalangeal fractures without rotation or displacement can be splinted using a dorsal foam splint that immobilizes joints on either side of the fracture. Those patients with rotational abnormalities or displacement should be referred to a hand surgeon to prevent permanent disability.

Evaluation of the sensory function of the fingers is also vitally important. In a finger with normal motor function but impaired sensation, the impairment may significantly limit the overall function of the individual digit and may affect the function of the hand itself. This part of the examination must obviously be performed prior to the administration of local anesthetic. In older children, two-point discrimination is tested using a paper clip opened and bent into a caliper with the points at 10 mm (see Fig. 103.2C). The child is asked to close his or her eyes, and the paper clip points are placed against the skin along the long axis of the finger. The touch should be relatively light so as to minimize the stimulation of pressure receptors. The patient is asked, “Do you feel one or two points?” The points of the paper clip are gradually brought closer together, and the test is repeated until the child reports feeling only one point. Two-point discrimination of 6 to 10 mm is normal for most children. It is important to assess sensation on both the radial and ulnar aspects of the finger as well as the dorsal and palmar sides. In cooperative younger children, it may only be possible to test light touch by asking the child whether he or she feels the touch of a finger or cotton-tipped swab on all aspects of the finger. With very young or uncooperative children, the clinician may not be able to discern the presence or absence of nerve injury. Indirect evidence of intact sensory innervation may be obtained by placing the finger in a bowl of warm water for 5 minutes. Intact innervation is indicated by wrinkling of the skin of the finger, whereas nerve injury results in persistence of smooth skin.

Vascular supply to the fingers is tested by assessing the capillary refilling time for the nail bed or fingertip pad. The tissue is compressed until it blanches and is then released. The

amount of time that it takes for the pink color to return is noted. Normal capillary refilling time is less than 2 seconds. In addition, if a sensory defect is noted in the context of a laceration, a vascular injury can be assumed.

amount of time that it takes for the pink color to return is noted. Normal capillary refilling time is less than 2 seconds. In addition, if a sensory defect is noted in the context of a laceration, a vascular injury can be assumed.

Subungual Hematoma

A subungual hematoma is an acute, painful collection of blood between the fingernail and the nail bed, typically the result of blunt trauma to the fingertip. A subungual hematoma collects when the highly vascular nail bed is transiently crushed and extravasation of blood occurs, creating a blue-black discoloration beneath the nail. The nail and its margins usually remain intact. Often, as the hematoma enlarges, pressure beneath the nail increases, which compresses highly sensitive nerve fibers in the nail bed and fingertip and results in significant pain. Typical mechanisms include trapping the fingertip in a closing door or window and blunt trauma from hammers and other heavy objects. Subungual hematomas are best treated by timely decompression. Nail trephination affords rapid and complete relief and is easily accomplished in an office or emergency setting.

In cases of subungual hematomas with disruption of the nail or its margins, the nail itself should be removed and the nail bed explored for lacerations requiring repair (2). An underlying distal phalanx fracture may be present, but hematoma size bears no direct correlation to the presence or absence of an underlying fracture (3). Any injury suspicious for fracture should be evaluated by plain radiography, as these injuries require immobilization (typically splinting). A displaced fracture of the distal phalanx can significantly disrupt the nail

bed. Historically, subungual hematomas larger than 50% of the nail plate were thought to require nail removal to assess and repair any underlying nail bed lacerations (4,5,6). However, a more recent study demonstrated that otherwise uncomplicated subungual hematomas of virtually any size can be adequately treated with trephination alone (3). No subsequent cosmetic deformities or complications were noted in this study, even in the presence of underlying nondisplaced fractures. Another study reported nail bed injuries in 11 of 94 patients with subungual hematoma, yet these injuries did not correlate with hematoma size or the presence of a fracture (7).

bed. Historically, subungual hematomas larger than 50% of the nail plate were thought to require nail removal to assess and repair any underlying nail bed lacerations (4,5,6). However, a more recent study demonstrated that otherwise uncomplicated subungual hematomas of virtually any size can be adequately treated with trephination alone (3). No subsequent cosmetic deformities or complications were noted in this study, even in the presence of underlying nondisplaced fractures. Another study reported nail bed injuries in 11 of 94 patients with subungual hematoma, yet these injuries did not correlate with hematoma size or the presence of a fracture (7).

A subungual hematoma usually remains liquefied for 24 to 36 hours (8). Therefore, drainage will still afford pain relief even if presentation is delayed. Relief of pain occurs rapidly once the hematoma is drained, and this should be performed as expeditiously as possible. However, trephination is unlikely to be successful beyond 48 hours after injury.

Equipment

Syringe with 27-gauge needle

Bupivacaine (0.25%) without epinephrine

Lidocaine (0.5% or 1%) without epinephrine

Antiseptic prep solution

Restraints (as needed)

Electrocautery device or, alternatively, a paper clip, butane lighter, and hemostats

Protective dressing

Procedure

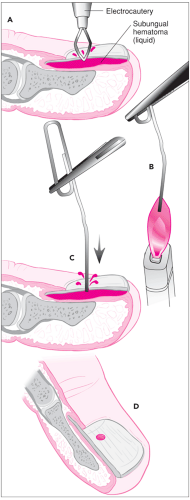

Nail trephination involves creating a hole in the nail over the hematoma to allow drainage of the underlying blood (Fig. 103.4). If the hole is too small, blood can clot within it, preventing complete drainage and adequate pain relief. A hole of 3 or 4 mm in diameter is usually adequate, and one large hole is better than several small ones, each of which may clot (2). Anesthetic blockade of the finger (see Chapter 35) should be considered for a highly anxious child or for a child with underlying fractures in whom pain will persist. Most children easily tolerate drainage, however, especially when performed quickly with an electrocautery wire device (9,10).

The overlying nail should be gently cleaned with antiseptic solution. If alcohol is used, it must be allowed to dry, as it can ignite when heated. The electrocautery wire is held perpendicular to the nail over the subungual hematoma (Fig. 103.4A). When the wire has heated sufficiently, gentle downward pressure is used to trephinate the nail. Blood will rapidly exit through the hole, and the remainder may be extruded by gentle pressure on the nail bed. A high-speed nail drill can also be used in a similar fashion. As an alternative, the clinician can apply an 18-gauge needle perpendicular to the nail plate and spin it back and forth between the fingers with gentle downward pressure until the nail is penetrated. While slower and more likely to cause pain to an unanesthetized finger, this method is effective. Finally, a paper clip held by hemostats

may be heated with a butane lighter and used to create a drainage hole using gentle downward pressure perpendicular to the nail. If performed correctly, the heated clip rapidly penetrates the nail and cools as it meets the underlying blood, with minimal discomfort to the patient. The paper clip must be steel and not aluminum, as aluminum will not generally stay hot enough to readily penetrate a fingernail.

may be heated with a butane lighter and used to create a drainage hole using gentle downward pressure perpendicular to the nail. If performed correctly, the heated clip rapidly penetrates the nail and cools as it meets the underlying blood, with minimal discomfort to the patient. The paper clip must be steel and not aluminum, as aluminum will not generally stay hot enough to readily penetrate a fingernail.

Perform a radiographic evaluation if a fracture is suspected.

Perform a digital nerve block if necessary.

Cleanse the area with an antiseptic preparation solution.

Trephinate the nail.

Apply a protective dressing.

Splint fractures for 14 days; instruct patient and parents to perform warm soaks.

After drainage, a protective dressing is applied, and the patient is instructed to soak the digit in warm water three times daily for 2 days, redressing it after each soak. Any underlying fracture requires splinting for at least 14 days and may require evaluation by a hand specialist.

Complications

Complications of nail trephination are rare. Some advocate routine antibiotic prophylaxis when a fracture accompanies a subungual hematoma to prevent infection, since trephination in such cases converts the underlying fracture into a potentially more serious open fracture (11). In a recent study, however, no infectious complications of trephination were noted in patients with underlying fractures who did not receive antibiotics (3). Routine antibiotic prophylaxis is probably unnecessary unless the child is immunocompromised or the vascular supply to the area is compromised (8). The parents and child should be warned that (a) blood may continue to ooze from the trephination site for 1 to 2 days; (b) the discoloration under the nail can persist days to weeks; and (c) the nail may fall off, and if so, it will take at least 3 to 4 months to grow in again (8). Carbon deposits may persist at the site of trephination but are benign (2).

Subungual Foreign Body

Foreign bodies lodged under the nail of either a finger or toe are painful and are a nidus for infection. Removal of the foreign body offers relief from pain, reduces the risk of infection, and can be performed in most outpatient settings.

Subungual foreign bodies are typically wedged between the nail and the nail bed, although penetration of either can occur. Mixed bacteria accompany the foreign body beneath the nail

and can cause infection. This is especially true of wooden foreign bodies. When a wooden foreign body is allowed to remain beneath the nail, subsequent infection is common.

and can cause infection. This is especially true of wooden foreign bodies. When a wooden foreign body is allowed to remain beneath the nail, subsequent infection is common.

The nail bed is highly innervated. Therefore, while removal of a subungual foreign body brings significant pain relief, inflammation of the nail bed typically results in some persistent discomfort. Importantly, timely removal limits the risk of infection. Radiographs are obtained to document the presence of a radiopaque foreign body or when a fracture is suspected. Consultation with a hand surgeon is advised for foreign bodies that are clearly infected, for foreign bodies that cannot be removed, or if concern exists regarding bony injury and possible subsequent osteomyelitis due to deep nail bed penetration.

Equipment

Syringe with 27-gauge needle

Bupivacaine (0.25%) without epinephrine

Lidocaine (0.5% or 1%) without epinephrine

Restraints as needed

Hemostats or fine forceps

Fine-tipped scissors

No. 11 scalpel blade

Sterile protective dressing

Procedure

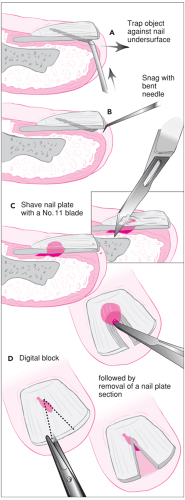

The finger with the foreign body is immobilized by taping the involved digit and adjacent finger(s) to a small pediatric arm board. The technique for removing the foreign body depends on the position of the foreign body beneath the nail (Fig. 103.5).

Perform a radiographic evaluation as needed to confirm the presence of a foreign body.

Perform a digital nerve block if necessary.

Remove the foreign body using appropriate technique based on nature of the object.

Clean and irrigate thoroughly.

Apply a protective dressing.

Prescribe antibiotic if there are signs of infection; instruct patient and parents to perform warm soaks.

A subungual foreign body that protrudes beyond the end of the nail is grasped with a hemostat or a pair of fine forceps and gently removed. If the protruding stump of the foreign body is not easily grasped at its distal aspect, it is pinned against the nail using the tip of fine-tipped scissors, a needle, or a No. 11 scalpel blade point. The foreign body is then gently drawn forward until it is out from beneath the nail (Fig. 103.5A).

Several methods can be used to remove a distal foreign body that cannot be grasped. A 25- or 27-gauge needle is bent at its tip to a 90-degree angle using a hemostat. The needle is inserted under the nail, rotated slightly to snag the object, and then gently withdrawn (Fig. 103.5B) (12). Alternatively, a No. 11 blade is held horizontally perpendicular to the nail and scraped proximally to distally across the nail overlying the foreign body (Fig. 103.5C). This procedure shaves down the nail until the foreign body is exposed and can be grasped and removed (10). Most children tolerate these methods without anesthesia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree