Malrotation

Paul T. Stockmann

Wayne State University, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, Michigan 48201.

Malrotation is the term used to define the group of congenital anomalies resulting from aberrant intestinal rotation and fixation that occurs during the first 3 months of gestation. In 1932 and 1937, William Ladd reported a series of surgically treated infants with congenital duodenal obstruction, including malrotation (1,2). His operation, the Ladd procedure, included unrotating the midgut volvulus, mobilization of the duodenum and right colon by division of the congenital adhesive bands, and placement of the colon in the left side of the abdomen. This operation remains the standard treatment for this malformation.

“Bilious emesis in a newborn is a surgical emergency until proven otherwise” is a classic axiom in pediatric surgery. Due to the risk for significant adverse outcome, malrotation should be the first consideration in the differential diagnosis. The anomalies of intestinal rotation and fixation consist of a spectrum of anatomic defects with a wide range of clinical findings. Patients can be entirely asymptomatic or may be extremely ill, with an acute midgut volvulus and impending intestinal necrosis or death. Although patients may present at any age, most of these anomalies become apparent clinically during infancy and early childhood. Prompt recognition and treatment should result in a satisfactory outcome with low morbidity and mortality in the majority of cases. Conversely, diagnostic or therapeutic delay can result in death or permanent disability such as short bowel syndrome.

The true incidence of the malrotation variants is not known, but symptomatic lesions have an incidence of approximately 1 in 6,000 live births. Nonrotation, a common form of malrotation, has been noted in 0.5% of large autopsy series and in 0.2% of gastrointestinal (GI) contrast studies. Incomplete rotation is the most common form leading to early (i.e., neonatal) symptomatic disease and surgery, and nonrotation is the more common variant seen in asymptomatic cases. For surgically treated cases, 70% to 80% are classified as incomplete rotation, and 10% to 20% are nonrotation. Malrotation is more common in males than in females. It is estimated that this anomaly is the cause of 6% of all neonatal intestinal obstructions (3,4,5).

EMBRYOLOGY

An understanding of the embryology of the intestinal tract in the first 3 months of fetal life is necessary to accurately identify and adequately treat the various types of malrotation (8). In the third week of gestation, the primitive alimentary tract is a simple tube lined with endoderm. It is divided into three distinct regions. The foregut is located within the headfold, and the hindgut is located within the tailfold. The midgut is the portion of bowel in between and is that part of the primitive GI tract that will herniate into the umbilical cord. This portion is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and will give rise to the alimentary tract extending from the duodenum to the transverse colon. The intestine returns into the abdomen by the twelfth week of gestation. Subsequently, a specific sequence of events occurs allowing rotation and fixation of the intestine and leading to the final position of the small and large bowel in postnatal life. Malrotation occurs when this dynamic sequence is incomplete or altered. This process is separated into three stages: herniation, return to the abdomen, and fixation.

Herniation

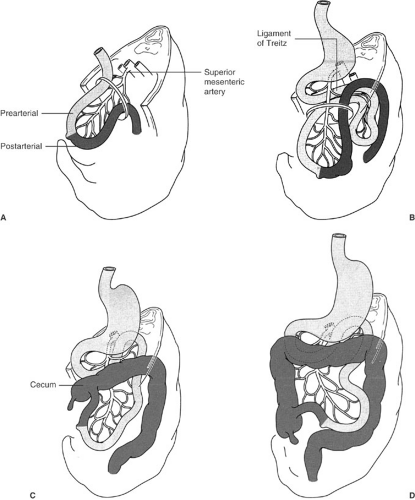

The midgut herniates into the yolk sac during the fifth week of gestation, led by the vitelline or omphalomesenteric duct at the apex. The SMA and its branches are centered within the primary loop and represent the axis for rotation. The proximal midgut is designated the duodenojejunal or prearterial limb, and the distal portion as the cecocolic or postarterial limb (Fig. 81-1A). The imaginary line of demarcation connects the omphalomesenteric duct and the origin of the SMA. Disproportionate growth and

elongation of the duodenojejunal segment occurs with an initial 180-degree counterclockwise rotation of the limb to the right of the SMA (Fig. 81-1B). The proximal portion of the duodenojejunal limb will eventually rotate 270 degrees to become fixed in the retroperitoneum posterior and to the left of the SMA. The prearterial limb will ultimately give rise to the duodenum, the jejunum, and the majority of the ileum (Fig. 81-1C). The cecocolic segment undergoes reciprocal 180-degree counterclockwise rotation of the limb to the left of the SMA. The ileocecal junction, located within the postarterial limb, will eventually rotate 270 degrees (Fig. 81-1D), moving anterior to the SMA and descending into the retroperitoneal position in the right iliac fossa. The cecocolic limb will ultimately give rise to the terminal ileum, cecum, and right and proximal transverse colon.

elongation of the duodenojejunal segment occurs with an initial 180-degree counterclockwise rotation of the limb to the right of the SMA (Fig. 81-1B). The proximal portion of the duodenojejunal limb will eventually rotate 270 degrees to become fixed in the retroperitoneum posterior and to the left of the SMA. The prearterial limb will ultimately give rise to the duodenum, the jejunum, and the majority of the ileum (Fig. 81-1C). The cecocolic segment undergoes reciprocal 180-degree counterclockwise rotation of the limb to the left of the SMA. The ileocecal junction, located within the postarterial limb, will eventually rotate 270 degrees (Fig. 81-1D), moving anterior to the SMA and descending into the retroperitoneal position in the right iliac fossa. The cecocolic limb will ultimately give rise to the terminal ileum, cecum, and right and proximal transverse colon.

Return to the Abdomen

The herniated midgut returns to the abdominal cavity between the tenth and twelfth week of gestation. Most of the important rotational anomalies are believed to occur due to altered or arrested development in this stage. The first segment to return to the abdomen is the duodenojejunal limb. During this process, the final 90 degrees of rotation occur to complete the 270-degree counterclockwise rotation around the SMA. The final configuration places the third portion of the duodenum posterior to the SMA and the ligament of Treitz in the left upper quadrant. The distal cecocolic limb returns next and also completes the terminal 90 degrees of the 270-degree rotation. The cecum and terminal ileum are the last portions of the midgut to return to the abdominal cavity. As a result, the transverse colon lies anterior to the SMA and the cecum is positioned in the right lower quadrant at level of the iliac fossa (Fig. 81-1E).

Fixation

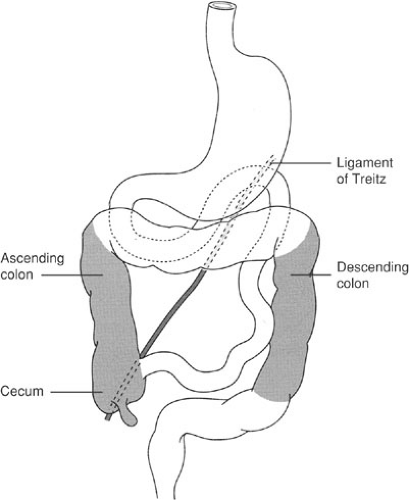

The final stage in the process of development of the midgut is fixation of the duodenojejunal junction in the left upper quadrant and the ileocecal junction in the right lower quadrant. This process begins during the twelfth week of gestation and continues until after birth. Normal fixation can occur only if midgut rotation has been completed appropriately. The majority of the duodenum, as well as the ascending and descending colon, become fixed to the retroperitoneum. The jejunum, ileum, and transverse colon remain the mobile, intraperitoneal portions of the midgut. With normal intestinal rotation and fixation, the root of the mesentery of the small intestine stretches from two fixed, retroperitoneal structures—the ligament of Treitz in the left upper abdomen and the cecum in the right lower quadrant (Fig. 81-2). The normal, broad-based small bowel mesentery is not at risk to undergo axial rotation and form a midgut volvulus. Aberrant intestinal rotation and fixation produce anatomic variations prone to intestinal obstruction. Inadequate rotation and fixation result in the formation of an abnormal small bowel mesentery: The proximal and distal midgut may be fused together with a common mesentery encircling the SMA. This narrowed, mobile mesenteric pedicle is prone to clockwise rotation around the axis of the SMA, with subsequent compression and obstruction of both the intestinal tract and the mesenteric vessels. The end result can be an acute closed-loop intestinal obstruction with vascular occlusion. These anomalies are also known to cause extrinsic compression and obstruction of the duodenum secondary to anomalous peritoneal (Ladd’s) bands. The bands extend from the retroperitoneum in the right upper quadrant and attach to the right colon, thus compressing the underlying duodenum.

CLASSIFICATION

Malrotation represents a spectrum of anomalies of intestinal rotation and fixation. The most common and clinically significant

abnormalities include nonrotation and incomplete rotation. Less common and more variable malformations include mixed rotational and fixation anomalies, as well as mesocolic hernias.

abnormalities include nonrotation and incomplete rotation. Less common and more variable malformations include mixed rotational and fixation anomalies, as well as mesocolic hernias.

Nonrotation

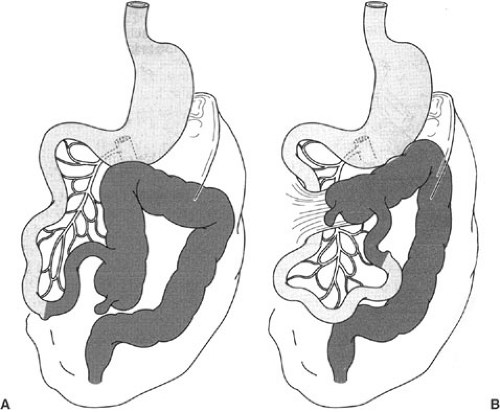

Nonrotation occurs as the result of failure of counterclockwise rotation of the midgut loop around the SMA. The duodenojejunal and cecocolic limbs undergo less than 90 degrees of counterclockwise rotation, and the cecocolic limb returns to the abdomen first instead of last. The duodenum does not rotate posterior to the SMA, and the ligament of Treitz fails to reach its normal position in the left upper quadrant. As a result, the colon resides in the left side of the abdomen with the cecum at or near the midline, and the small intestine rests in the right side of the abdomen (Fig. 81-3A). The duodenum can be compressed in the right upper quadrant by abnormal peritoneal bands. In addition, the normal C-shaped configuration is lost, and the duodenum may have a tortuous course along the right side of the abdomen. Portions of the duodenum and proximal jejunum are often fused to the ascending colon by anomalous peritoneal attachments. The midgut mesentery is narrow and highly mobile.

Patients with nonrotation have the anatomic risk factors for the development of acute midgut volvulus and extrinsic duodenal obstruction. Nonrotation is a common form of malrotation, reported to occur in approximately 0.5% of autopsies and in 0.2% of GI contrast studies (5). It is about twice as frequent in males as in females, and is commonly associated with both abdominal wall defects and diaphragmatic hernias. Affected individuals may be asymptomatic; others can present with symptomatic anomalies at any age, but most become evident in early childhood. Nonrotation is less commonly associated with obstruction and volvulus than incomplete rotation.

Incomplete Rotation

This variation of malrotation occurs as the result of partial rotation of the cecocolic and duodenojejunal limbs around the SMA. The counterclockwise rotation occurs only to approximately 180 degrees rather than the normal 270-degree rotation arc. As a result, there is abnormal positioning of the proximal small bowel and the cecum (Fig. 81-3B). The cecum and the first part of the ascending colon are located in the epigastrium against the third portion of the duodenum and override the superior mesenteric vessels. The configuration of the duodenum is abnormal, with the ligament of Treitz displaced inferiorly, to the right of the midline, and anterior to its normal position in the left upper quadrant. Retroperitoneal bands originating from the right upper quadrant to the cecum and ascending colon can compress the second portion of the duodenum. Incomplete rotation is a common variant of malrotation. The majority of patients present with symptomatic lesions during infancy. Incomplete rotation is the most common form of malrotation treated surgically.

The distinction between nonrotation and incomplete rotation is primarily arbitrary and based on the extent of inadequate midgut rotation and fixation rather than distinct pathologic entities. Approximately 90% of patients with symptomatic malrotation will have either nonrotation or incomplete rotation.

Mixed Rotational and Fixation Anomalies

The mixed anomalies are less common than nonrotation and incomplete rotation, and the anatomic variations are more diverse. These malformations result from arrested or aberrant rotation, or fixation of either the duodenojejunal limb or the cecocolic limb, or both. These anomalies also have a wide range of clinical presentations. Patients may be asymptomatic with trivial defects or develop intestinal obstruction resulting from a volvulus or extrinsic compression.

Reverse rotation is one type of mixed rotational anomaly (3). In this rare variant, midgut rotation occurs in a clockwise rather than a counterclockwise direction around the SMA axis so the duodenojejunal loop ultimately resides anterior rather than posterior to the SMA. If the cecocolic limb also undergoes reverse rotation, the transverse colon lies posterior to the SMA. Therefore, the anatomic arrangement is exactly reversed from normal. That is, the third portion of the duodenum is anterior to the SMA, which is anterior to the transverse colon. The clinical presentation is that of intestinal obstruction resulting from extrinsic compression of the transverse colon by the overriding superior mesenteric vessels or an ileocecal volvulus caused by inadequate fixation of the right colon. If reverse rotation of the duodenojejunal limb occurs in association with normal clockwise rotation of the cecocolic limb, a right mesocolic hernia will result. The hernia sac is formed by the mesentery of the right colon as it rotates to the right lower quadrant.

Another mixed anomaly occurs with incomplete rotation of the duodenojejunal limb, and normal rotation and fixation of the cecocolic limb. The ligament of Treitz is abnormally positioned inferiorly and to the right of the midline. The midgut mesentery is narrowed even though the ileocecal junction is fixed in the normal location in the right lower quadrant. Ladd’s bands may be present and cause partial obstruction of the duodenum. These anomalies have a variable clinical presentation ranging from no symptoms to duodenal obstruction. The small bowel mesentery is somewhat narrow, but the risk of a volvulus is fairly low.

Another variation includes normal rotation and fixation of the duodenojejunal limb with nonrotation of the cecocolic limb, resulting in a malpositioned cecum in the epigastrium with Ladd’s bands extending across the second portion of the duodenum. In this instance, the mesenteric pedicle is narrowed with the cecum and terminal ileum adjacent to the proximal jejunum. Therefore, patients with this malformation are at risk for a midgut volvulus.

Mesocolic Hernias

Mesocolic or paraduodenal hernias are another rare anomaly associated with abnormal development and fixation of the right or left mesocolon. Normally, the ascending and descending colons are fixed to the retroperitoneum. In mesocolic hernias, abnormalities in rotation and fixation lead to the development of potential spaces formed between the mesocolon and the retroperitoneum.

Right mesocolic hernias occur as a result of nonrotation (or reverse rotation) of the duodenojejunal segment combined with incomplete rotation and fixation of the cecocolic segment. The cecum has attachments to the retroperitoneum in the right upper quadrant, and the incompletely rotated small intestine becomes trapped within a hernia sac formed from the right mesocolon. The ligament of Treitz is absent, and the small bowel resides on the right side of the abdomen, posterior to the cecum and right colon.

A left mesocolic hernia occurs when the duodenojejunal segment rotates posterior and to the left of the SMA, but then invaginates into the left mesocolon posterior to the inferior mesenteric vein and into the retroperitoneum. The cecocolic segment rotates normally and becomes fixed in the retroperitoneum. The small bowel becomes trapped within a sac formed by the left mesocolon with the inferior mesenteric vein forming the anterior aspect of the neck of the sac. All mesocolic hernias are true internal hernias that can cause incarceration, obstruction, and strangulation of the intestine.

ASSOCIATED ANOMALIES

Rotational anomalies are associated with many other congenital malformations. Nonrotation is present in nearly all cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, and omphalocele. In addition, 30% to 60% of patients with malrotation have other anomalies or conditions (6,7,8,9,10). The malformations involve the GI tract (50%), central nervous system (12%), cardiac (12%), respiratory (12%), and genitourinary (6%) systems. Atresia of the small bowel has an association with malrotation. In some cases, the cause of the atresia may be due to malrotation with antenatal midgut volvulus and intestinal ischemia, infarction, and resorption.

Other anomalies reported with malrotation include Meckel’s diverticulum, duodenal web or stenosis, Hirschsprung’s disease, imperforate anus, esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula, congenital short gut, biliary atresia, prune belly and megacystis-microcolon syndrome, cardiac anomalies, situs inversus, mesenteric cyst, pyloric stenosis, intussusception, and abnormalities of the biliary tree (11,12,13,14,15,16). A genetic basis has been proposed for a familial form of malrotation (17).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Patients with malrotation may have one of several clinical presentations. The range includes the asymptomatic adult

to the critically ill newborn with an abdominal catastrophe. Typical presentations involve newborns and infants with acute intestinal obstruction secondary to midgut volvulus or duodenal compression. Atypical presentations include older individuals with chronic or intermittent symptoms and less specific findings. Malrotation may be discovered incidentally during radiographic studies or operative exploration.

to the critically ill newborn with an abdominal catastrophe. Typical presentations involve newborns and infants with acute intestinal obstruction secondary to midgut volvulus or duodenal compression. Atypical presentations include older individuals with chronic or intermittent symptoms and less specific findings. Malrotation may be discovered incidentally during radiographic studies or operative exploration.

Approximately 66% of patients with malrotation become symptomatic during the first month of life, and nearly 90% present within the first year of life. Symptoms usually result from duodenal obstruction. The duodenum is the point of obstruction, and acute midgut volvulus with intestinal ischemia is the most significant and potentially life-threatening complication of malrotation. Although the majority of patients with acute midgut volvulus present within the first year of life, patients with malrotation are at risk to develop a volvulus at any age. Partial or complete duodenal obstruction also occurs from extrinsic compression from abnormal peritoneal (Ladd’s) bands.

Atypical presentations are more common in older children and adults. The symptoms are more chronic and intermittent and result from partial or intermittent duodenal obstruction or a chronic midgut volvulus. These include abdominal pain and vomiting associated with weight loss or failure to thrive, and other nonspecific GI complaints (11,12).

Midgut Volvulus

Acute midgut volvulus is a true surgical emergency. Torsion of the narrow mesenteric pedicle produces an acute closed-loop intestinal obstruction and vascular insufficiency. Intestinal ischemia and necrosis may proceed rapidly unless treated promptly. Midgut volvulus is present in up to 50% of patients operated on for malrotation (7,9,11). The presentation of midgut volvulus commonly begins with the sudden onset of bilious vomiting in a previously healthy newborn. Bilious emesis is the cardinal feature of neonatal intestinal obstruction, and mandates urgent evaluation to exclude malrotation with volvulus. Although bilious vomiting may be due to nonsurgical disorders such as sepsis, intracranial hemorrhage, and electrolyte abnormalities, malrotation must be rapidly excluded from the differential diagnosis in order to prevent significant morbidity and mortality. Occult or gross blood in the stool may be due to intestinal ischemia and mucosal injury. Initially, the abdomen is nondistended, but persistent intestinal obstruction and vascular insufficiency leads to abdominal distention and tenderness with lethargy and other signs of shock. Abdominal radiographs initially may not be diagnostic. A high index of suspicion is important because the complications of vascular compromise can advance rapidly. Transmural intestinal necrosis and sepsis occur with hypotension, metabolic acidosis, respiratory and renal failure, and thrombocytopenia, all consistent with the abdominal catastrophe. If the history and physical findings are highly suspicious for acute midgut volvulus, urgent operative intervention is indicated without confirmatory radiographic studies. This is justified due to the disastrous consequences related to delayed treatment of this potentially correctable process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree