Jejunoileal Atresia

Milissa A. McKee

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06520.

The evolution of the management of neonatal intestinal atresia parallels the development of pediatric surgery as a specialty and illustrates the necessity of surgeons dedicated to the care of children. Prior to 1950, the mortality rate in cases of atresia exceeded 90%. Since the mid-1960s, advances in surgical technique have allowed successful surgical treatment of this condition. Advances in general neonatal intensive care have been instrumental in further improving survival. The ability to provide total parenteral nutrition (TPN) as well as mechanical ventilation and general anesthesia to these vulnerable infants has reduced mortality to 1% to 10% in most series (1,2). Although the diagnosis of intestinal atresia or stenosis is a classic cause of neonatal intestinal obstruction, it remains a relatively rare occurrence. The estimated incidence ranges from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 5,000 births in population-based studies (3). This incidence is similar to the overall incidence of duodenal atresia and far higher than colonic atresia. Knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of these abnormalities continues to be essential to provide afflicted infants with the necessary treatment to achieve the expected successful outcome. The pediatric surgeon plays a central role in initial lifesaving surgical intervention, as well as in the recognition and management of the potential for long-term morbidity. Although most of these patients will recover over the initial hospitalization, a subset of these children will have prolonged needs related to malabsorption, short gut, TPN cholestasis, limited venous access, and infectious complications. Most cases are sporadic without specific etiologic agent or genetic pattern identified. There have been reports of familial cases and a higher incidence in twins. The ratio of males to females is equal. Associated extraintestinal anomalies are rare with a few notable exceptions, such as cystic fibrosis (4). As many as 20% of infants with one atresia will have multiple atresias (1).

ETIOLOGY

Normal development of the midgut is a complicated process (5). First recognizable by the third week in gestation, the midgut begins as a simple tubular structure. It then elongates considerably, herniating from the abdominal cavity where it undergoes rotation. It then returns to the abdomen and develops fixation to attain its normal configuration. Rapid epithelial proliferation between the fifth and eighth weeks may result in transient obliteration of the intestinal lumen. Somatic growth continues throughout gestation. Insults during this normal development are believed to result in the pathology seen in humans. The vast majority of patients demonstrate complete atresias with a smaller proportion (less than 10%). having stenosis or webs. These abnormalities may be seen anywhere in the jejunum or ileum.

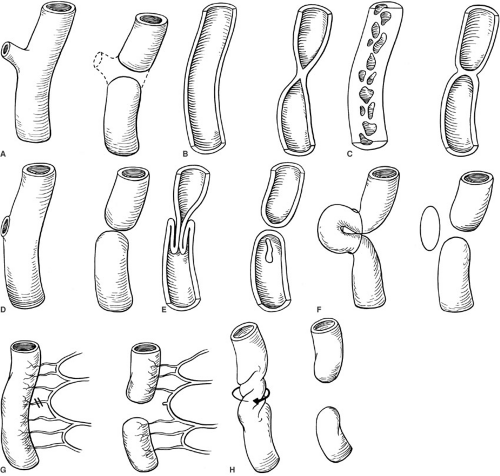

There are many theories to explain the pathogenesis of jejunoileal atresia; however, no one concept has been universally accepted to account for the entire spectrum of anomalies seen in clinical practice. Figure 78-1 summarizes a variety of proposed theories. The best evidence to date implicates in utero vascular accidents resulting in intestinal atresia. In a seminal work by Louw and Barnard (6), the mesenteric vascular supply of fetal dogs was ligated late in gestation. The intestine was then examined after birth and noted to demonstrate the variety of anatomic defects seen in human clinical practice. Similar trials have been designed in many different animal models confirming the development of intestinal atresias in the setting of in utero mesenteric ischemia (7,8,9). The anatomic, functional, and pathologic findings are all strikingly similar to the clinical condition found in humans.

Additional observations in these models indicate that in utero intestinal perforation may heal with a variety of outcomes in the intestine, ranging from stenosis and atresia to normal appearance of involved segments with no evidence of injury. Furthermore, intestinal atresia has been noted to occur in association with a variety of insults that

have in common mesenteric ischemia, such as volvulus, intussusception, internal hernia, and abdominal wall defects with constriction at the fascial defect (5,10).

have in common mesenteric ischemia, such as volvulus, intussusception, internal hernia, and abdominal wall defects with constriction at the fascial defect (5,10).

Clinical evidence also supports the idea that atresia results from an insult late in gestation. It has been noted by many authors that bile, hair, and epithelial cells are commonly found distal to the atretic region, suggesting the lumen was patent at some time. Other extraabdominal anomalies are rare, likewise suggesting a late insult.

The main alternative theory is failure of recanalization. First hypothesized in 1900, this theory is a very plausible explanation for duodenal atresia, but is difficult to

correlate with the previously mentioned clinical observations and the extensive evidence that mesenteric ischemia is involved in the pathogenesis of jejunoileal atresia.

correlate with the previously mentioned clinical observations and the extensive evidence that mesenteric ischemia is involved in the pathogenesis of jejunoileal atresia.

Current research is ongoing to further elucidate the functional abnormalities associated with intestinal atresia. This will hopefully improve our understanding and management of these patients. Intestinal dysmotility (11), altered brush-border enzyme function, and malabsorption have all been noted in patients with atresia (12,13,14). Successful treatments for these abnormalities would be a tremendous step forward in the care of these patients with the potential to reduce long-term morbidity.

CLASSIFICATION

Jejujunoileal atresia is separated into four major groups, following the classification system revised by Grosfield into its current form (15). This classification is also summarized in Fig. 78-2.

Type I: Membranous atresia or web with intact mesentery The bowel and its mesentery remain in continuity to visual inspection. The proximal bowel dilates, depending on the degree of obstruction that may be partial if the web is fenestrated or complete. The web may be stretched for some distance within the lumen

creating a windsock deformity. Overall, the bowel length is normal.

Type II: Blind ends of the bowel with intact mesentery The proximal and distal loops of bowel are blind ending, typically connected by a fibrous cord. The underlying mesentery remains intact, and the bowel length is again usually normal.

Type IIIa: Blind ending loops with mesenteric defect This form of atresia results in an often largely dilated blind proximal loop completely separated from a collapsed distal loop. There is an intervening mesenteric defect of variable size, and the total length of bowel may also be affected.

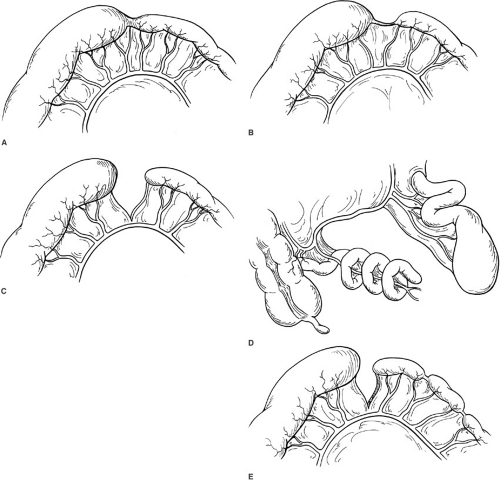

Type IIIb: Blind ending proximal loop, absent superior mesenteric artery, distal corkscrew bowel around marginal vessel, so-called “apple peel” atresia or Christmas tree deformity

This is a much more complex form of atresia likely related to a near catastrophic in utero vascular event, such as complete occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery based on thrombosis, embolic phenomena, or volvulus. The proximal bowel is dilated and bulbous in appearance, and ends blindly in a proximal location, often just past the ligament of Treitz or equivalent length. The distal bowel is quite small and wrapped around a marginal vessel from the ileocolic or right colic vessels, which is the entire blood supply to the midgut. This results in the typical appearance described as an “apple peel” atresia. An example of type IIIb atresia is shown in Fig. 78-3. In almost all cases, there is a significant loss of overall bowel length. Owing to both the large disparity in size between the proximal and distal bowel, as well as the tenuous vascular supply, the technical aspects of repair are challenging. These infants tend to be premature, small for gestational age, malrotated, and have a much higher potential for morbidity and mortality than other types of atresia. Also, in contrast to other forms of atresia, type IIIb atresias are believed to be associated with some form of genetic inheritance with a complex form of penetrance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree