Male Genital Tract

Julian Wan

David A. Bloom

Department of Urology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-0330.

Department of Urology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-0330.

Sexual differentiation begins at fertilization. The fertilizing sperm carrying either an X or Y chromosome joins the X chromosome of the egg to determine the karyotype (XX for female or XY for male). Chromosomal sex guides gonadal differentiation. The gonads are initially bipotential and indistinguishable. Local influences engendered by the chromosomal sex direct the development of either an ovary or testicle. The SRY gene on the short arm of chromosome Y influences the gonad to become a testis. Gonadal sex in turn produces the appearance of anatomic characteristics known as phenotypic sex. Each step in this sequence depends on the preceding step.

The fetal testis produces two important products. The Leydig cells secrete testosterone and the Sertoli cells produce müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS). Both are crucial for normal male phenotypic development. MIS causes local regression of the paramesonephric ducts (müllerian system), and testosterone stimulates ipsilateral mesonephric (wolffian) duct development. The male genital tract is formed largely between the sixth and thirteenth weeks of gestation. During the latter two thirds of gestation, the testicles descend to the scrotum and the external genitalia undergo differential growth.

Although internal ductal development is testosterone mediated, virilization of the male external genitalia is governed by dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Normal external genitalia development requires the presence and cellular recognition of DHT. The enzyme 5-α reductase converts testosterone into DHT. Androgen receptors sensitive to DHT are then stimulated and institute the changes in external genitalia: the genital tubercle becomes the penis, the urethral folds tabularize, and the genital swellings gather to form the scrotum.

PHALLUS

Embryology

The genital tubercle forms ventral to the cloaca by the fourth week of gestation and is identical in both sexes until age 9 weeks. Under the influence of DHT, the male genital tubercle enlarges, elongates, and assumes a cylindrical shape. A circumferential groove demarcates the glans. Elongation pulls the urethral folds forward, creating the lateral walls of the urethral groove. The folds migrate toward the midline and fuse by 12 weeks forming the penile urethra, the ventral surface of the phallus, and median raphe. Mesenchyme coalesces around the deepening groove to form the corpus spongiosum. The urethral groove, having originated from endoderm grows toward but does not reach the tip of the phallus. The distal end of the urethra is formed during the fourth month of gestation, when an invagination at the glans penis forms the external meatus. This part of the urethra is ectodermal in origin. The glanular invagination meets the elongating urethral groove to complete the urethra and simultaneously preputial development begins as an epithelial fold growing over the glans. The surrounding pleat of skin is completed at birth.

Anatomy

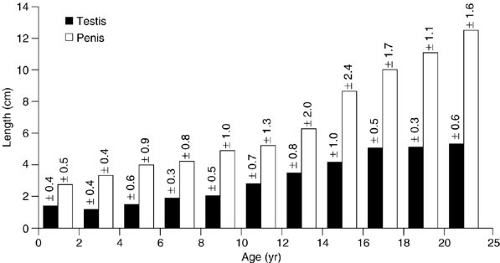

The normal full-term infant penis is 3.5 cm in stretched length and 1.1 cm in diameter. Stretched penile length from the pubic symphysis to the tip of the glans correlates with erect length. Care should be taken to depress the suprapubic fat pad completely to get an accurate measurement and a length less than 2.5 cm is abnormal. Penile size often increases during the first 6 months after delivery, because of the physiologic surge of testosterone in the male infant at 2 to 3 months of age. From this time until puberty, however, only modest phallic growth occurs (Fig. 98-1). The urethra and external meatus of a premature or infant male should

accommodate a 5F feeding tube. An 8F tube should pass without difficulty by age 1 year.

accommodate a 5F feeding tube. An 8F tube should pass without difficulty by age 1 year.

The prepuce protects the delicate urethral meatus from minor trauma. The inner epithelial surface is fused to the glans penis in infancy, obscuring the glans and meatus. This normal anatomic condition should not be confused with phimosis. True phimosis is a pathologic condition seen later in life, wherein a fibrotic preputial ring develops. During the first 3 to 5 years of life, the natural process of intermittent erections and progressive accumulation of desquamated residue (smegma) separate the inner epithelial surface of the prepuce from the glans. By 3 years of age, 90% of foreskins are easily retractable. However, many boys have persistent isolated areas of adhesion, particularly around the coronal margin.

CIRCUMCISION

Circumcision is the most common surgical procedure in the United States. It is usually performed because of religious preference or for social reasons (i.e., older brothers and father are circumcised). In 1999, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) observed that routine newborn circumcision may not be necessary (1). Families should be instructed in care of normal foreskin. The American Academy of Pediatrics brochure is a good instructional guide (2). Forcible retraction of the prepuce is painful, harmful, and unnecessary. Tearing the prepuce places the child at risk for cicatrix formation and phimosis, and is therefore inadvisable. Medical benefits of circumcision include prevention of penile carcinoma, phimosis, balanoposthitis, and neonatal urinary tract infection (UTI) (1,3,4). An uncircumcised male neonate is 20 times more likely to have a UTI than a circumcised infant, because of preputial colonization of the prepuce by urinary pathogens (2,3). The higher incidence of UTI occurs only during the first year of life, and beyond that time, circumcision has not been shown to decrease infections. Circumcision should be discussed with the family of any male infant with a UTI or vesicoureteral reflux, although suppressive antibiotics for the first year of life are an option. Disadvantages of neonatal circumcision include meatitis and meatal stenosis because the protective covering of the prepuce is lost. In addition, a boy may develop chordee or concealed penis, and the procedure is not without discomfort.

Circumcision is usually performed in one of two ways. Clamp or bell circumcision is reserved for infants younger than a few months of age. A freehand technique by dorsal slit or sleeve method is preferred for older children. It is important to recognize the features of a normal and abnormal penis. Children with chordee, hypospadias, and buried or webbed penises should not undergo routine neonatal circumcision. The clamp and bell devices commonly used in neonatal circumcision were designed for use on a normal penis and when applied inappropriately can cause injury to the urethra or yield a poor cosmetic result. The prepuce may be an important source of tissue for later reconstruction. No patient who may need future hypospadias repair should undergo routine circumcision. Be wary of the child described as having a “natural circumcision.” Usually these are boys with a prominent dorsal hooded foreskin and a subtle distal hypospadias, and a hypoplastic corpus spongiosum. Whenever a circumcision is performed, the surgeon must carefully examine the underlying glans and meatus for occult hypospadias with normal foreskin.

Neonatal Circumcision

Infant circumcision is not without complications and should be performed by persons experienced in the technique who will evaluate the child postoperatively to gauge the results. The infant is placed on a papoose board restraint. Local anesthesia can be safely administered, with

1 mL or less of 0.25% lidocaine as a dorsal nerve block or circumferential subcutaneous block. The anesthetic must not be injected intravascularly or into the corporal body. A small dorsal slit is usually required to expose the glans, and all adhesions are detached by blunt dissection. The clamp or bell is applied visually; experience helps in judging the proper amount of skin to excise. With the clamp technique, the clamp is left in place for 5 minutes for hemostasis before redundant skin is excised. A suture with surgeon’s knot is applied on the bell device. Topical anesthesia (eutectic mixture of local anesthetic—EMLA) applied directly to the penile skin is an alternative form of anesthesia. Although easy to administer, it may not be as effective as injection blocks (5). Electrocautery should never be used when a metal clamp technique is employed. To guard against meatal stenosis, petroleum, or antibiotic ointment should be daubed on the meatus at each diaper change.

1 mL or less of 0.25% lidocaine as a dorsal nerve block or circumferential subcutaneous block. The anesthetic must not be injected intravascularly or into the corporal body. A small dorsal slit is usually required to expose the glans, and all adhesions are detached by blunt dissection. The clamp or bell is applied visually; experience helps in judging the proper amount of skin to excise. With the clamp technique, the clamp is left in place for 5 minutes for hemostasis before redundant skin is excised. A suture with surgeon’s knot is applied on the bell device. Topical anesthesia (eutectic mixture of local anesthetic—EMLA) applied directly to the penile skin is an alternative form of anesthesia. Although easy to administer, it may not be as effective as injection blocks (5). Electrocautery should never be used when a metal clamp technique is employed. To guard against meatal stenosis, petroleum, or antibiotic ointment should be daubed on the meatus at each diaper change.

Freehand Circumcision

Circumcision after 3 months of age is best performed under general anesthesia with a freehand sleeve technique. Adhesions between glans and prepuce are gently reduced using a mosquito clamp dipped in iodine solution, and the location of the meatus should be ascertained. A circumferential incision of the prepuce is made 6 to 8 mm proximal to the coronal sulcus, carried to the relatively avascular subcutaneous plane. The prepuce is then reduced and a parallel incision is made in the distal penile skin overlying the prepuce, at the level of the coronal sulcus. The isolated sleeve of tissue is removed. Compression is applied to the exposed shaft for several minutes, and larger vessels are ligated or fulgurated. Particular attention should be directed to the skin edges, where small vessels may retract. The proximal and distal skin edges are aligned and reapproximated with an interrupted, small (6–0 or 7–0) absorbable suture. Compressive dressings are rarely needed. If ventral skin is deficient or bleeding is difficult to control at the frenulum, this area can be reapproximated with vertical sutures to control bleeding and create additional ventral skin.

Complications

Careful neonatal circumcisions have a low rate of complications (less than 0.5%) (6). Fortunately, the complications are usually minor and heal with conservative management. Excessive skin resection can lead to tension and skin separation, which usually heals well by secondary intention particularly in the newborn. When separation occurs after neonatal circumcision, apply copious amounts of antibiotic salve with each diaper change and be patient. After 2 to 3 weeks, the edema subsides allowing better assessment of the penis. Often the separation will have closed. Postoperative bleeding often responds to manual pressure or suture ligation and rarely requires exploration. Postoperative dressings are not required, which obviates the chance of urinary retention from a constrictive dressing.

Complications that require intervention include urethrocutaneous fistula, concealed penis, dense adhesions between glans and shaft, and meatal stenosis. A fistula is often the result of unrecognized deficient spongiosum. Concealed penis occurs following overzealous skin excision, or when a scarred preputial ring forms distal to the glans. Dense adhesions may cause pain with erection and should be divided. Meatal stenosis may ensue because of irritation of the unprotected meatus; liberal use of ointment postoperatively prevents this complication.

Prepuce Abnormalities

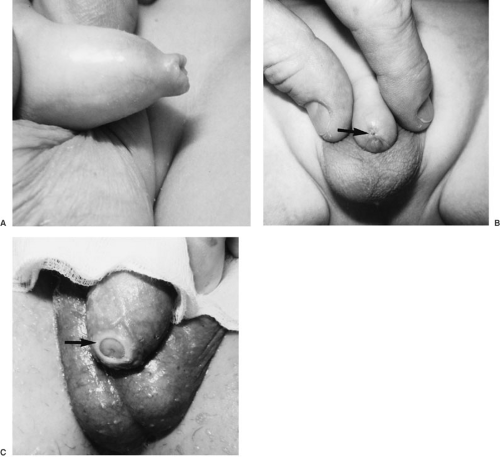

True phimosis refers to a circumferential preputial ring that prevents foreskin retraction. This differs from the physiologic inability to retract the foreskin in male infants. Preputial tears or cracks from natural erection, forcible retraction, or infection can lead to cicatrix formation and narrowing of the preputial aperture (Fig. 98-2). Circumcision or dorsal slit effectively corrects the abnormality.

Phimosis is the leading cause of preputial inflammation, or posthitis. Balanitis is inflammation or infection of the glans penis. The terms posthitis and balanitis are often used interchangeably, and may coexist when posthitis to involve the glans. The inflammation is usually self-limited and responds to topical or oral antibiotics. Recurrent episodes are managed with circumcision following resolution of acute inflammation. Infection that spreads to the penile shaft and abdominal wall should be managed aggressively with parenteral antibiotics. Uncontrolled cellulitis may progress proximally, along tissue planes, to form a necrotizing fasciitis that requires operative intervention.

STRUCTURAL ABNORMALITIES

Microphallus

A penis smaller than two standard deviations below mean normal length is termed a microphallus (7). This term excludes hypospadias, ambiguous genitalia, buried penis, webbed penis, and other abnormalities. These conditions can confuse and mislead the casual examiner. Normal neonatal mean stretched penile length is 3.5 cm, and an infant male penis should measure at least 2.5 cm. During the second and third trimester, fetal androgens stimulate penile growth. Any condition that interferes with fetal testicular testosterone production after organogenesis is complete (first trimester) can cause micropenis. Hypogonadism also produces an underdeveloped scrotum and small, undescended testes.

An abnormality in the hypothalamus–pituitary–testis axis can result in testicular failure. Primary testicular failure (end-organ hypogonadism) can be determined by measuring serum testosterone before and after human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is administered. The normal response is a fourfold increase in testosterone within 24 hours of the final dose of hCG. Secondary gonadal failure (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) with microphallus occurs in conditions such as anencephaly; pituitary agenesis; and Kallman, Noonan, and Prader-Willi syndromes. Microphallus is described as idiopathic when no deficit is found in the endocrine axis. Because differential diagnosis includes the intersex disorders, an appropriate evaluation should include karyotype and endocrine status.

The growth potential of a small penis can be assessed by evaluating for a response to androgen administration. Testosterone may be given as a topical or parenteral preparation. Because the absorption of testosterone creams is variable, a 3-month trial of monthly intramuscular testosterone enanthate, 25 to 50 mg, is more dependable. Such a short course of androgens does not result in premature closure of the epiphyseal growth plates. Management of boys who do respond is controversial because many show no significant response to the androgen surge at puberty. However, many men with microphallus are sexually active and well adjusted, showing that penile function is satisfactory despite the small size (8).

Buried and Concealed Penis

The terms buried penis and concealed penis are often used interchangeably; however, they describe different conditions (9). A buried penis is normal in size, but appears small because of an overlying generous suprapubic fat pad

that hides the normal penile shaft. Occasionally, a large hydrocele may obscure the shaft, resulting in a buried penis. Manual depression of the fat pad, an important maneuver when measuring penile length, reveals the normal penis. For many of these boys, the melting away of baby fat with growth, genital lengthening and pubic hair growth solve the cosmetic dilemma at adolescence. For some boys and parents, however, the embarrassment and emotional trauma of an obscured penis mandate repair. Successful surgical correction can produce enormous improvement in a boy’s self-esteem. Circumcision will unmask the glans, and liposuction or excision of the suprapubic fat will address the obscuring panniculus. Occasionally, additional surgical maneuvers are required, including release of dysgenetic Scarpa’s fascia below the fat pad, where it continues as the dartos layer of the penis, and anchoring suprapubic skin to the fascia overlying the pubis and anterior abdominal wall. There has to be a strong commitment to a diet and exercise weight reduction program as part of the overall treatment plan; otherwise, the fat pad will rapidly reform.

that hides the normal penile shaft. Occasionally, a large hydrocele may obscure the shaft, resulting in a buried penis. Manual depression of the fat pad, an important maneuver when measuring penile length, reveals the normal penis. For many of these boys, the melting away of baby fat with growth, genital lengthening and pubic hair growth solve the cosmetic dilemma at adolescence. For some boys and parents, however, the embarrassment and emotional trauma of an obscured penis mandate repair. Successful surgical correction can produce enormous improvement in a boy’s self-esteem. Circumcision will unmask the glans, and liposuction or excision of the suprapubic fat will address the obscuring panniculus. Occasionally, additional surgical maneuvers are required, including release of dysgenetic Scarpa’s fascia below the fat pad, where it continues as the dartos layer of the penis, and anchoring suprapubic skin to the fascia overlying the pubis and anterior abdominal wall. There has to be a strong commitment to a diet and exercise weight reduction program as part of the overall treatment plan; otherwise, the fat pad will rapidly reform.

Concealed (trapped) penis occurs after circumcision. A cicatrix forms at the anastomotic line, and the penis retracts proximal to the scar. Surgical revision may be challenging because a limited amount of shaft skin remains. Dorsal slit or removal of the cicatrical ring is required.

FUNCTIONAL DEVIATION

Penile Torsion

Penile torsion is a rotational defect of the penile shaft that is of more cosmetic than functional significance. The anomaly occurs in 1% to 2% of males and is more common in patients with hypospadias. The median raphe spirals obliquely around the shaft, producing a rotation that is usually less than 90 degrees. If the erections are straight and the child can void without difficulty, mild forms of penile torsion can be left alone. Mild forms are usually repairable by penile degloving and skin reorientation. Severe rotational defects of 90 to 180 degrees are repaired by mobilizing penile skin to the base of the penis, incising any chordee, and resecting Buck’s fascia. Torsion also occurs iatrogenically following circumcision or hypospadias repair. Most cases are minimally rotated, not associated with chordee, and rarely are a functional problem.

Penile Bending (Chordee)

The term chordee refers to a ventral bend of the shaft on erection. Chordee is a normal stage in embryonic penile development; the ventral bend may persist in premature male infants, but it usually corrects spontaneously within several months. Chordee is usually associated with hypospadias, in which deficient ventral penile development includes skin, spongiosum, Buck’s fascia, and urethra. Hypospadias should not be corrected without fixing the chordee.

Chordee may also occur in spite of a normal urethra, although a preputial dorsal hood and thin ventral skin often coexist. Such chordee result from skin tethering, a urethral bowstring defect, or corporal disproportion. Vaginal penetration is difficult with an erect penile bend of greater than 45 degrees. Release of skin and dysgenetic bands may not completely straighten the penis. In such cases, dorsal plication or elliptical wedge excision of the corporal body at the point of maximum bend may be required. Another technique is to place a plicating stitch exactly in the midline of the degloved dorsal penis. This position avoids the neurovascular bundles that pass slightly lateral on each corporal body (10). If urethral tethering exists, mobilization of the urethra within the spongiosum corrects the bend. Occasionally the urethra must be divided and repaired. Intraoperative erections induced by saline injection of the corpora must be performed to gauge the defect and repair.

MEATAL STENOSIS

Stenosis of the urethral meatus usually occurs years after neonatal circumcision. The delicate meatus is susceptible to inflammation from local trauma such as from rubbing against a diaper or underwear. Meatitis progresses to cicatrix formation, with narrowing of the orifice. Deflected urinary stream and prolonged voiding times are typically noted by parents after a child is toilet trained. The classic history is that the urine stream deflects upward or sprays. A fine, forceful stream may emanate from a pinpoint meatus. Irritative voiding symptoms, such as dysuria and urgency, rarely occur without a concomitant UTI. Isolated meatal stenosis without infection does not require radiographic assessment of the urinary tract or cystoscopy. When stenosis is suspected, the meatus can be calibrated with small catheters or sounds. If stenosis is not severe, parents can be taught to perform daily obturation with a feeding tube or the tip of an ophthalmic ointment tube. Significant stenosis should be surgically corrected by a ventral incision, followed by a 3-month program of daily calibration of the urethra with a catheter, to ensure adequate opening.

PRIAPISM

Priapism is the involuntary and prolonged erection of the corpora cavernosa. Recurrent and prolonged bouts of priapism can lead to corporal fibrosis and impotence. The causes of priapism can be categorized into two broad groups: low flow or high flow. The majority of patients have low-flow priapism. Decreased venous outflow leads

to increased intracavernous pressure and subsequent decreased arterial inflow. The venoocclusion leads to stasis of blood, hypoxia, and acidosis. The glans penis and spongiosum are flaccid. The most common low-flow situation in pediatric patients occurs with sickle cell disease or trait; about 5% of these patients experience priapism. The erection occurs as part of a diffuse sickle crisis or as an isolated event. Sickle crisis is managed by transfusion to reduce the hemoglobin S level, as well as oxygenation, hydration, alkalinization, and pain control. Aspiration with irrigation of the corporal bodies with an α-adrenergic agent can also be tried, but is usually unsuccessful in sickle cell patients unless systemic management of the crisis has been also started. Phenylephrine, 100 to 200 μg, can be used; patients need careful monitoring, particularly those with a history of cardiovascular disease. When conservative management fails, surgical construction of a shunt connecting the corpora cavernosa to the spongiosum may be effective temporarily; ultimately, however, these close. Recurrent bouts of priapism can result in impotence due to the repetitive pressure damage to the corporal bodies.

to increased intracavernous pressure and subsequent decreased arterial inflow. The venoocclusion leads to stasis of blood, hypoxia, and acidosis. The glans penis and spongiosum are flaccid. The most common low-flow situation in pediatric patients occurs with sickle cell disease or trait; about 5% of these patients experience priapism. The erection occurs as part of a diffuse sickle crisis or as an isolated event. Sickle crisis is managed by transfusion to reduce the hemoglobin S level, as well as oxygenation, hydration, alkalinization, and pain control. Aspiration with irrigation of the corporal bodies with an α-adrenergic agent can also be tried, but is usually unsuccessful in sickle cell patients unless systemic management of the crisis has been also started. Phenylephrine, 100 to 200 μg, can be used; patients need careful monitoring, particularly those with a history of cardiovascular disease. When conservative management fails, surgical construction of a shunt connecting the corpora cavernosa to the spongiosum may be effective temporarily; ultimately, however, these close. Recurrent bouts of priapism can result in impotence due to the repetitive pressure damage to the corporal bodies.

Leukemia is another cause of childhood priapism. Although chronic granulocytic leukemia accounts for only a small percentage of pediatric leukemias, one-half of all leukemic priapism occurs in these patients. Leukemic cells appear to cause microvascular occlusion within the corporal bodies, but other possible factors include leukemic infiltration of the sacral nerves or central nervous system as well as abdominal and pelvic venous obstruction. Treatment is directed at lowering the circulating leukocyte count. Shunts may be necessary for refractory cases. Other etiologies for priapism in the child include blunt perineal trauma, spinal cord injury, medications (tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, hydralazine, prazosin, guanethidine, heparin, and cocaine), and retroperitoneal fibrosarcomas. As with sickle cell disease and leukemia, treatment is aimed at the underlying disease process. Fat emulsions of 20% infused as part of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) have been associated with priapism. It is believed that the fat emulsion increases blood coagulability, distorts erythrocytes, and, promotes adhesion and clumping. Antidepressants, such as trazadone, and antipsychotics, such as chlorpromazine have also been associated with priapism.

High flow priapism is caused by unrestrained arterial inflow. Because the problem is not one of venoocclusion, there is no hypoxia and acidosis. Almost all cases of high-flow priapism are due to penile and perineal trauma. An injury to the cavernosal artery results in a cavernosus-to-corporal body fistula. The key diagnostic finding in high-flow priapism is the discovery of well-oxygenated red blood upon corporal aspiration. In contrast to the flaccidity found in low-flow priapism, the glans and spongiosum in high-flow priapism is engorged with blood and is quite firm.

TESTIS

Embryology

The SRY gene facilitates gonadal differentiation into a testis such that Sertoli cells develop in weeks 6 and 7, and shortly thereafter produce MIS, which causes ipsilateral müllerian duct regression. By the ninth week, Leydig cells produce testosterone, which stimulates wolffian duct development. The testis and caput epididymis arise from the genital ridge, whereas the epididymal body and vas deferens originate from mesonephric tubules. Canalization of the rete testis and mesonephric tubules begins about week 12 and is complete by puberty. Testicular descent is a third-trimester event; prenatal ultrasounds typically show no descent prior to 28 weeks. Many theories have been proposed to explain testis descent, including gubernacular traction, differential somatic growth, intraabdominal pressure, epididymal maturation, and hormone milieu. In all likelihood, a combination of events and influences under androgen regulation leads to normal testis descent.

Anatomy

The average length of the infant testis is 1.4 to 1.6 cm. The testis grows minimally in the prepubertal years; significant growth is not noted until onset of puberty (Fig. 98-1). In boys with monorchidism, a solitary testis may undergo compensatory hypertrophy, and any solitary infant testis longer than 2 cm suggests contralateral testicular absence (11).

Appendages of the testis and epididymis are vestigial embryologic remnants (Fig. 98-3). An appendix testis, present on approximately 90% of testes, is a remnant of the müllerian ducts. The müllerian system completely regresses in males, except for its cranial remnant, which persists as the appendix testis, and the extreme lower end remnant, which forms the prostatic utricle. The appendix testis is located on the cranial surface of the testis, and occasionally at the testis–epididymal junction. The remaining appendages are vestigial remnants of the mesonephric tubules. An appendix epididymis is located on the globus major of the epididymis in 34% of males. The paradidymis is a remnant structure found at the junction of the epididymis and vas deferens. These remnants serve no known function, except to confound the differential diagnosis of an acute scrotum.

Physiology

The infant testis is hormonally active, not quiescent as was once believed. Normal activity in the first 6 months of postnatal life seems to be crucial for the testis to develop normal adult function. A postnatal surge of gonadotropins at 60 to 90 days results in proliferation of Leydig cells by 3 months (12). Leydig cells respond with a testosterone

surge that triggers germ cell development. The first step in postnatal germ cell development is the transformation of gonocytes to adult dark (Ad) spermatogonia, which is completed by 6 months. These spermatogonia may represent the pool of stem cells that replenish germ cells throughout life. The second stage of development occurs around 3 years of age, when the Ad spermatogonia transform to primary spermatocytes. Alterations in this normal cascade of events may result in a dysfunctional adult testis (12). As the child matures, spermatogonia populate the base of the seminiferous tubules, and spermatogenesis begins at puberty.

surge that triggers germ cell development. The first step in postnatal germ cell development is the transformation of gonocytes to adult dark (Ad) spermatogonia, which is completed by 6 months. These spermatogonia may represent the pool of stem cells that replenish germ cells throughout life. The second stage of development occurs around 3 years of age, when the Ad spermatogonia transform to primary spermatocytes. Alterations in this normal cascade of events may result in a dysfunctional adult testis (12). As the child matures, spermatogonia populate the base of the seminiferous tubules, and spermatogenesis begins at puberty.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree