Law, Regulation, Quality Assurance, and Risk Management

Harold M. Ginzburg

Mhairi G. MacDonald

▪ BASIC LEGAL AND REGULATORY CONCEPTS

Introduction

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” is an insight often attributed to George Santayana, a 19th to 20th century philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. Edmund Burke wrote, in the 18th century, “Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.” Thus, a brief historical overview is provided in this chapter.

The Pharaohs had their physicians, the slaves did not. Throughout recorded history, the affluent had either sole or better access to medicinal herbs and health care advisors. Disappointed leaders banished or executed their unsuccessful health care providers. The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, estimated to have been written nearly 4,000 years ago, is generally considered the first codified legal document that addressed medical issues, including wages and scaled punishments (1). The entire document consisted of 282 laws chipped into stone and clay tablets. The Affordable Care Act, 2010, (also known as “Obamacare”) is more than 1,000 pages in length and is but one of thousands of legislative acts or laws that govern the 21st century practice of the healing arts within the United States (2). Each state functions as a sovereign nation and may have its own legal codes and regulations governing the healing arts and professions and the medications prescribed and dispensed. As medicine evolved from the domain of the priest or shaman herbalists to that of physician specialists, the remedies for medical injury adjudicated by the legal system also evolved, in Western Society, from the Code of Hammurabi (“an eye for an eye”/and/or coin(s) of silver and gold for permanent injury, untoward or unexpected consequences or death), to confinement for criminal activities such as assault and battery (unwanted or unauthorized touching of a patient), to pecuniary or monetary damages for reported present and future emotional and physical damages.

Community standards for what was considered the minimum threshold of care below which the conduct of a health care professional would be sanctioned were developed. In the Middle Ages, in England, compensation was to be paid for errors of medical judgment or perceived less than satisfactory results. In other domains, if a physician or barber-surgeon were found responsible for poor medical care, he or she could be deformed in a similar manner to the damaged patient. Thus, physicians and barber-surgeons were not motivated to treat patients with complicated illnesses unless the patient and his or her extended family clearly understood that treatment would be palliative at best.

Today, inadequate (from the patient or patient’s family’s perspective) communication, coupled with unrealistic expectations for treatment outcome, produces family anger and guilt and may lead to litigation. The family expects success, as they define it. The neonatologist’s definition of success in an individual case may differ substantially from that of the family. Litigation may be initiated when negligence has actually occurred or when it is perceived to have occurred. Poor communication and failure to convey empathy toward the family members can be as self-destructive for the health care provider as a faulty knowledge base, performing in an unprofessional manner, or functioning in an impaired capacity. Good medical knowledge and practical clinical skills alone are not sufficient to preclude involvement in a malpractice litigation.

Large institutions with a substantial number of health care providers can be perceived as being impersonal. If, in addition, the communication of members of the health care team with the patient or family members is inadequate, the lack of understanding that results may form the primary basis for litigation.

Patients, their families, and the public at large need to understand that health care providers are not able to succeed all the time. Sometimes, the nature and extent of the disease is too life threatening or debilitating; sometimes, the state-of-the-art knowledge of the pathophysiology and/or treatment is not yet adequately developed; sometimes, the treatment options are fraught with significant risks; sometimes, errors in judgment and skill are made. Over the past few years, some states (within the United States) have passed laws that are referred to as “I am sorry” laws, which allow health care providers to speak frankly with a patient and/or his or her family and explain what may have gone wrong in a manner that promotes dialogue and compassion and potentially avoids subsequent litigation. Coincident with the writing of this chapter, in March 2014, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom introduced regulations that mandate that health care providers reveal and explain all significant medical errors. In addition, the Joint Commission on Accreditation (TJC) in the United States now requires health care organizations to disclose unanticipated injuries or complications, perform root cause analyses as to what occurred and why it occurred, and institute an action plan to prevent future occurrences (3). In similar fashion, the Joint Commission International (TJCI) publishes the International Accreditation Standards for Hospitals in nations willing to accept their accreditation standards (see “Accreditation of Health Care Activities”) (4). It appears that regulatory agencies are developing an understanding that this level of transparency should be the gold standard, and frank communication has been shown to decrease the incidence of malpractice litigation (5). Prior to the middle of the 20th century, members of the healing profession functioned as an integral part of their local community. Since the 1940s, there has been a progressive separation of health care providers from the communities they serve; this process has been accelerated by the advent of highly subspecialized, expensive intensive care. Neonatologists function in a crisis environment with little or no prior knowledge of their patients’ family unit.

Isolation of patients from health care providers, except in times of crisis, can lead to poor or limited communication and unrealistic expectations.

Responsibility and Liability

The mundane aspects of health care and treatment, such as scheduling of appointments, documentation of procedures, and understanding of the federal, state, and local guidelines, procedures, policies, regulations, and laws, are frequently the basis for confrontations between members of the medical and legal professions.

The vast majority of health care education, within the United States, pertains to understanding basic sciences and providing clinical services. Little formal systematic attention and education, within the healing arts, are given to the myriad of governmental policies, procedures, and regulations that control all aspects of health care delivery.

Medical care is a legal contract between the health care professional and the patient. In almost all instances, if the patient is unable, because of age and/or illness and/or linguistic and/or cultural perspective, to render informed educated consent, then others must provide such consent. Thus, as a patient is registered into a health care system, examined, or interviewed, law and medicine become intimately intertwined.

The basic legal considerations relating to the care and treatment of any patient, and particularly, a neonate, flow from the following four concepts:

The duty to act. When does the health care professional-patient or health care facility-patient relationship commence?

Knowledge and application of hospital policies and local, state, and federal mandates. What resources are available to facilitate information transfer to health care facilities and service providers?

Responsibility and accountability of the health care provider (individual or organization) to provide adequate care and treatment. Who is responsible for the decisions made in the provision of health care? Who monitors the quality of the services provided? Who ensures that the services provided are consistent with hospital policies and local, state, and federal mandates?

Information transfer to patients and their families or guardians. Who obtains educated informed consent, in what manner, and with what documentation? Who is responsible for providing ongoing medical information to the families or guardians of neonates and ensuring that the information, and the implications of the information, are understood? State and federal legislation, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 (6) and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (OBAMACARE) (2), do not set standards for the manner in which a clinician may or should communicate with a patient, parent, or guardian.

Defensive Medicine

Defensive medicine has become a medical term of art. It should connote a thoughtful systematic approach to health care, rather than the demonstration of poor judgment such as the excessive ordering of investigatory studies because of anticipatory fear of litigation for malpractice. Medical malpractice lawsuits are based on the principle of negligence. Negligence implies some wrongful act of commission or omission. The essence of negligence is unreasonableness.

Due Care

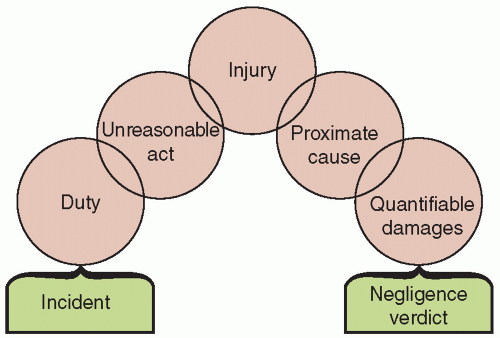

Due care is simply reasonable conduct (7). In order for negligence to be demonstrated in a courtroom, the injured person/plaintiff must demonstrate that (a) there was a legal duty owed to him or her; (b) there was a breach of that duty (a deviation from the accepted standard of care); (c) as a result of the duty and the breach thereof, damages or an injury occurred; and (d) the damages or injury can be determined to have been caused by, or shown to have flowed from, the care or lack of care provided by the health care provider(s) and/or organization responsible for the environment in which the health care was provided (Fig. 9.1).

Quality assurance and risk management aspects of medical care are relatively recent innovations designed to improve patient care and outcome. Quality assurance activities accept the legal and medical position that a health care provider owes a duty to the patient to provide reasonable medical care, consistent with available resources. There are inherent, irreducible risks in the delivery of health care and treatment, and quality assurance and risk management assessments are designed to identify and limit the risks.

Informed consent that includes a relative risk assessment of potential complications can be used to document educated (8), informed consent. The informed consent provides a written mechanism to explain to the patient and his or her family and guardians that there are always inherent risks involved in a medical intervention, which must be weighed against the inherent risks involved in not rendering that same medical intervention. The balance of relative risks needs to be understood by the health care provider and the patient and/or parent/guardian.

The Duty to Act

The duty to act is determined when the health care professional-patient or organization-patient relationship commences (7). A “duty” is a legal and ethical responsibility. There is no legal duty, under most circumstances, for a health care provider or institution to accept a patient for care unless they hold themselves out as providing emergency care or they are required to do so by law, regulation, or contract. The federal government, through the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), states that if a medical center, hospital, or physician represents themselves, to the public, as a source of emergency medical care and/or specialty care, and the community has come to expect such care, then a patient cannot be arbitrarily denied such services (9). Once a health care service is initiated, a health care provider/institution-patient relationship exists, a duty is created, and there is then a legal and moral obligation not to abandon the patient. Further, the care that is being provided must be adequate under the circumstances. The moral and legal obligation that attaches precludes abandonment or “dumping” of the patient (9). A referring hospital transferring an infant to another institution for further care is not perceived as abandoning the patient as long as the reason for transfer is medical and not financial. The senior medical person responsible for the transport, whether stationed at a hospital or directly providing patient care during transport, is deemed to be supervising the health care until the transport team transfers care to the clinical staff at the receiving medical facility.

The complexity of health care responsibility and liability increased rapidly during the 20th century. Public health care facilities have existed since the Middle Ages. Commencing in the 13th century, the Hotel Dieu in Paris provided indigent care for many centuries. In the United States, city, municipal, state, and federal public hospitals provided, and continue to provide, care for those unable to obtain it elsewhere. Historically, these physicians and hospitals were not held liable for the outcome of care that was provided free of charge. This doctrine of charitable immunity protected hospitals from legal liability if medical negligence occurred within their boundaries. However, an individual’s inability to pay for medical care no longer affects his or her ability to demand and receive services that are commensurate with those provided to patients who pay for their care directly or through third-party payment systems. Thus, providing care to patients who are unable to pay no longer protects a health care provider or medical institution from liability for negligence or malpractice. Physicians, other health providers, suppliers, and manufacturers of equipment, medical devices, and medicines can now all be sued for negligence and be held individually or jointly liable for their own actions, the actions of those that they supervise, and actions performed by members of their health care team.

Licensure; Interstate-International Practice

In the United States, health care providers (physicians, nurses, emergency medical technicians, respiratory therapists, etc.) may be licensed in more than one state. These health care providers, in general, must be licensed in the state in which they maintain their primary office or place of employment. The authorities in most, but not all, states are not concerned about whether a health care provider who enters the state solely to transport a patient to another health care facility is licensed in that state; however, they are concerned that the individuals involved in the transport are competent to perform their job.

An individual who enters a state, regardless of the reason, will be subject to the laws of that state. The most obvious analogy is that if a driver is involved in an accident, he or she is subject to the laws of the state in which the accident occurred, not those of the state that issued the driving license; this legal principle also applies to medical transport vehicle operators (10). Failure to obtain informed consent for transport may result in litigation in the state in which it was inadequately obtained or in the state to which the patient was transferred (see also Chapter 5).

Patients and their guardians may initiate medical malpractice litigation in the state in which they reside, the state in which the alleged negligence occurred, the state in which the hospital is located, or the state in which the physician resides. If the patient/plaintiff can show that his or her residence is in a different state from that of the defendant/hospital and defendant/health care provider, then the plaintiff may commence the litigation in a federal court because the matter involves diversity of jurisdiction, that is, opposing parties are located in two or more states. The defendant may also request that the matter be removed to the federal court system because of diversity of jurisdiction (11). Most plaintiffs prefer state courts, especially if the defendant is from a different state. Some state courts are known for their large awards to plaintiffs, whereas others are known to be more sympathetic to defendants/health care providers; forum shopping does occur.

Advances in what was previously called telephone-linked care (TLC) and is now referred to as “telemedicine,” include videoconferencing and sharing of electronic information across state, national, and international borders (see also Chapter 7). In the United States, final revisions to telemedicine standards, from The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), have hastened the expansion of data sharing. CMS has adopted new rules (and regulations) addressing credentialing for physicians involved in telemedicine (12). Home-bound patients can be brought into the electronic era with passive remote monitoring and active data access to their medical records. In the United States, the patients are generally perceived as “owning” their medical records. Licensing and scope of practice issues are beginning to transcend state and national borders, resulting in licensing and quality of care issues for state licensing authorities. For more than 15 years, throughout the world, telemedicine has been integrated into direct patient care, monitoring patient progress, and serving as an expander for specialized medical expertise and technology (e.g., the interpretation of neonatal radiologic or cardiologic films and tracings at a remote site with the results being electronically communicated back to the source hospital) (13). The American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Clinical Information Technology (COCIT) was established in 2002 and was instrumental in the development of the Academy’s Child Health Informatics Center (CHIC) whose goal it is to support the development of health information technology (HIT) and use of electronic health records (EHRs).

Telemedicine, as one would expect, shares the same issues that face-to-face medicine must address: regulatory issues including standard and quality of care, credentialing and licensure, liability and scope of practice, informed consent, confidentiality, privacy, and reimbursement.

Telemedicine has been practiced for as long as there has been the telephone. The neonatologist, especially at a tertiary medical center, can regularly be expected to engage in “telehealth.” This includes providing consultation, arranging transportation, and interpreting radiographic, cardiologic, and other data, as well as professional education, community health education, and public health activities. The American Medical Association and American Telemedicine Association have urged medical specialty societies to develop appropriate practice standards. U.S. federal health care agencies, such as the Indian Health Service and the Department of Veterans Affairs, and nongovernmental managed care organizations have embraced telemedicine. Louisiana, in 1995, became the first state to enact legislation dealing with telemedicine reimbursement (14) that specifies a certain reimbursement rate for physicians at the originating site and includes language prohibiting insurance carriers from discriminating against telemedicine as a medium for delivering health care services.

At the present time, issues relating to cross-state licensure are still perceived as potential barriers to the expansion of telemedicine (15), especially now that reimbursement is possible. States license physicians and other health care providers within their boundaries, but the federal government and, in particular, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have the authority to prepare national licensure standards as they relate to national programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. In the future, there may be alternative approaches to state licensure for health care professionals. Regardless of the legal issues surrounding telemedicine, neonatologists increasingly cross state and international boundaries. Thus, the need to appreciate that the laws of political jurisdictions other than their home state or country may significantly impact the manner in which they practice and the associated liability.

Medical Torts and Contracts

The legal system is divided into two broad areas—civil litigation and criminal prosecution. Civil litigation is based on the need to correct or remedy a wrong between one individual, corporation, or partnership and another individual, corporation, or partnership. Criminal prosecution is instituted to correct a wrong against the community. In a civil litigation matter (or case), the plaintiff is the party initiating the lawsuit and alleging the wrong; the lawsuit is filed against the party (defendant) who is accused of causing the damage. In a criminal prosecution, the plaintiff is the government (local, state, federal) alleging that the community has been harmed by the action or inaction of a party (also known as the defendant). Civil matters resulting in litigation generally are either contract disputes or torts. A contract dispute occurs when two or more parties have entered into an agreement and one or more parties believe that the terms and conditions of the agreement, either an oral or a written contract, have not been met. It is important to appreciate that, in a court, in general, most oral contracts have the same weight as written contracts (there are notable exceptions when it comes to the transfer of ownership of real property).

A personal tort is an injury to a person or his or her reputation or feelings that directly results from a violation of a duty owed to the plaintiff (in medical malpractice cases, this is usually the patient) and produces damage. The remedy in any civil matter, after the nature and extent of the damages have been proved to the court (a judge with or without a jury), is determined by a preponderance of evidence (more than 50.01%) (16). Thus, “to a reasonable medical degree of certainty” means that it is more likely than not “true” and it is that standard upon which there are usually monetary damages awarded if the matter is found in favor of the plaintiff. The preponderance of the evidence rule is a threshold test (17). In general, either the plaintiff proves that the damages were more likely to have been caused by the defendant than by

any other source and that he or she is, therefore, entitled to full compensation, or he or she fails to meet the burden of proof and is entitled to nothing (18). In most instances in the United States, each side pays for its own legal services, regardless of the outcome of the case. In other countries, such as in the United Kingdom, this is not usually the case.

any other source and that he or she is, therefore, entitled to full compensation, or he or she fails to meet the burden of proof and is entitled to nothing (18). In most instances in the United States, each side pays for its own legal services, regardless of the outcome of the case. In other countries, such as in the United Kingdom, this is not usually the case.

Battery

Battery is a tort; it is an intentional and volitional act, without consent, which results in touching that causes harm (e.g., the touching of a patient’s body without consent). A technical battery can occur when there is no actual harm but touching occurred without consent. Patient care, even with a beneficial outcome but without informed consent, is considered to be a battery.

Plaintiffs may sue for an injury that occurred as a result of negligence or a tort (physical or mental harm), or both. Because the criminal court usually will not award monetary damages to the victim of a crime and because the standard of proof for conviction, in the United States, is “beyond a reasonable doubt” (quantitatively, this can be conceptualized as at least 95% certain), plaintiffs usually prefer to sue for injuries from a tort in civil court. In civil litigation, monetary damages may be awarded, and if the injury is determined to be egregious, punitive damages as a punishment and example to others may also be awarded.

Professional Negligence

Negligence is “conduct, and not a state of mind” (19), and it “involves an unreasonably great risk of causing damage” (19) and is “conduct which falls below the standard established by the law for the protection of others against unreasonable risk of harm” (20,21).

Professional negligence, or medical malpractice, is a special instance or type of negligence. The medical profession is held to a specific minimum level of performance based on the possession, or claim of possession, of “special knowledge or skills” that have been accrued through specialized education, training, and experience.

Ely and associates (22) found that when family physicians recalled memorable errors, the majority fell into the following categories: physician distracters (hurried or overburdened), process of care factors (premature closure of the diagnostic process and thus failure to identify the appropriate diagnosis), patient-related factors (misleading normal laboratory results, incorrect or inadequate medical/psychosocial history), and physician factors (lack of knowledge, inadequately aggressive patient management). Understanding the common causes of errors alerts the practitioner to situations when and where, in the evaluation and treatment process, errors are most likely to occur.

The Elements of a Malpractice Case

To establish a prima facie medical malpractice case (one that still appears obvious after reviewing the medical evidence), the patient/plaintiff must demonstrate (Fig. 9.1) that (a) there is a duty on the part of the defendant/health care provider and/or defendant/health care facility to the patient/plaintiff, (b) the defendant failed to conform his or her conduct to the standard of care required by the relationship, (c) an injury to that patient/plaintiff resulted from that failure, (d) the injury was the proximate cause, without other extraneous interventions and as a result of that injury, and (e) quantifiable damages may be calculated—then a negligence verdict, in favor of the plaintiff, may be rendered (23).

Generally, in order for the plaintiff to establish a claim of medical malpractice, the plaintiff must establish by medical expert testimony (a) what the applicable standard of care/knowledge base was at the time of the injury, (b) how the defendant breached or violated that standard of care, and (c) that the breach or violation (also referred to as the negligence) was the proximate cause of the injury.

A medical malpractice action can only proceed if the court determines that there is a genuine issue of material fact and if damages are quantifiable (e.g., the future costs of treatment, economic lost value of productive activities, etc.).

The most difficult element to prove is whether or not the care was adequate. The plaintiff usually must provide expert witnesses to establish what a prudent health care provider in similar circumstances might have done; what would be considered an acceptable standard of care rather than ideal or extraordinary care.

More than 130 years ago, in Massachusetts, it was held that a physician in a small town was bound to have only the skill that physicians of ordinary ability and skill in similar localities possessed. The court believed that a small-town physician should not be expected to have the skill of a physician practicing the same specialty in a large city (24). It was also held that a physician was required to use only ordinary skill and diligence, the average of that possessed by the profession as a body, and not by the thoroughly educated (25). However, in the age of the Internet, and with continuing medical education classes available locally and at national medical conferences, a health care provider is no longer excused for failing to keep up with medical progress in his or her specialty area.

Courts admit medical evidence based upon rules of evidence. In 1993, the United States Supreme Court in Daubert v Merrill Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ruled that the Federal Rules of Evidence standards for acceptance of evidence would be used (26). In Daubert, the Supreme Court focused upon the admissibility of scientific expert testimony. It pointed out that such testimony is admissible only if it is both relevant and reliable. In 1996, Kumho Tire Corporation v. Carmichael, the Supreme Court addressed the issue of how Daubert applies to the testimony of engineers and other experts who are not scientists (27). The Supreme Court, in Kumho, concluded that Daubert‘s general holding—setting forth the trial judge’s general “gatekeeping” obligation—applies not only to testimony based on “scientific” knowledge but also to testimony based on “technical” and “other specialized” knowledge.

The Daubert case was an attempt to prevent junk science from distracting the jury. The court held that scientific (medical) evidence had to be grounded in relevant scientific principles. The four criteria the court established are as follows: (a) whether the theory or technique has been tested; (b) whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication; (c) the known or potential rate of error of the method used and the existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique’s operation; and (d) whether the theory or method has been generally accepted by the scientific community. Thus, publication in a peer-reviewed or peer-refereed journal alone is not sufficient qualification for acceptance of evidence in a courtroom. The state and federal district (trial) court judges maintain the latitude to permit or exclude experts, based on the perceived scientific merit of the information they intend to provide to the court and, thus, to the jury. The fundamental issue for a clinician is not an understanding of the rules of evidence and the workings of the civil justice system but practicing medicine and acting in a professional manner, as documented in a patient’s medical record. If there is missing information, the presumption is usually made that the clinical data was not obtained or the procedure was not performed.

Many states have medical peer-review panels in place. In these states, before a medical malpractice case may be heard in a court, the facts of the case are presented to the medical review panel on behalf of both the plaintiff and defendant. The medical facts often are buttressed by the opinions of retained medical experts for both sides. In some states, the medical review panel is composed of attorneys and physicians; in other states, the medical review panel is chaired by an attorney and comprises physicians in the same or similar medical specialty as the physician defendant. Even when there is a finding for the defendant by the medical review panel,

the plaintiff may continue litigation in the local court. However, the findings of the medical review panel are admissible on behalf of either the plaintiffs or defendants.

the plaintiff may continue litigation in the local court. However, the findings of the medical review panel are admissible on behalf of either the plaintiffs or defendants.

Res ipsa loquitur

There are circumstances in which no expert witness is required to corroborate the findings of negligence. The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur essentially means that the thing or deed speaks for itself. Under such circumstances, the negligence is inferred from the act itself, that is, proof from circumstantial evidence. In the classic case Ybarra v Spangard, a patient was well prior to being anesthetized for an appendectomy, and when he woke up, he had an injury to his arm (28). Clearly, the patient could not determine how his arm was injured; the operating room and recovery room staff either could not or would not explain the etiology of the injury. The court found for the injured plaintiff without the introduction of any expert witnesses because (a) the plaintiff had not done anything that in any way could have contributed to the injury, (b) the injury could not have occurred unless someone was negligent, and (c) the instrumentalities (hospital staff and physicians) that allegedly caused the injury were at all times under the control of the defendant hospital.

Informed Consent

Informed consent requires that sound, reasonable, comprehensible, and relevant information be provided by a health care professional to a competent individual (patient or parent/guardian) for the purpose of eliciting a voluntary and educated decision by that patient (or guardian) about the advisability of permitting one course of clinical action as opposed to another (20). Physicians and other health care providers are held to have a fiduciary duty to their patients. Such a duty exists when one individual relies on another because of the unequal possession of information. The failure to obtain proper informed consent may result in the defendant/health care provider (often the physician) or defendant/hospital being sued for battery in some states or for negligence in others.

According to the battery theory, the defendant is to be held liable if any deliberate (not careless or accidental) action resulted in physical contact. The contact must have occurred under circumstances in which the plaintiff/patient did not provide either express or implied permission and the defendant/health care provider knew or should have known that the action was unauthorized. If the scope of consent obtained from the patient is exceeded, a claim of battery is proper. The plaintiff in Mohr v Williams consented to have surgery performed on her right ear (29). During the procedure, the surgeon determined that the right ear was not sufficiently diseased to require surgery, but the left ear required surgery. Because the patient was already anesthetized, the surgeon performed the operation. The operation was a success, but the patient successfully sued for battery. The court held that there was no informed consent for an operation to the left ear. Thus, it is not necessary for injury to occur for damages to be awarded; demonstration that there was unauthorized touching may be sufficient. In this instance, the court found that there was no medical emergency that would have threatened the plaintiff/patient if the surgery had not immediately commenced. If there had been evidence of a medical emergency, the court’s decision might have been different.

Failure to specifically identify the risks that accompany a surgical procedure also can result in a successful claim of battery. In Canterbury v Spence, the plaintiff/patient successfully proved that he was not informed of the risks attendant to the surgical procedure and that had he known them he would not have given permission (30). The court held that the physician has a duty to disclose all reasonable risks of a surgical procedure and, because he failed to perform that duty, the court held him liable for damages to the patient. The court noted that the concept of informed consent might be more appropriately replaced with the concept of educated consent (8). The court also articulated an objective standard that could be used in legal cases involving informed consent. This objective standard is based on what a reasonable person in circumstances similar to that of the patient would have decided if he or she had been provided with an adequate amount of information. Therefore, the central issue in a medical battery case is whether an educated, effective, or valid consent was given for the procedure that actually was performed.

A physician is not required to disclose every possible risk to a patient for fear of being guilty of battery (31). The court in Cooper v Roberts held that “[t]he physician is bound to disclose only those risks which a reasonable man would consider material to his decision whether or not to undergo treatment” (32). Thus, the court stated that such a standard creates no unreasonable burden for the physician. However, the physician must disclose risks that are material and feasible alternatives that are available. The information should be provided in a language and manner that reflects the emotional and educational status of the patient or, when the patient is a neonate, the parent(s) or guardian(s). In Davis v Wyeth Laboratories, the Court held that any medical complication or risk that has a probability of greater than 1:1,000 should be included in the informed consent (33).

When a therapeutic procedure is for the benefit of a minor, the decision to proceed usually belongs to the parent or legal guardian. The failure of the parent or guardian to consent to blood transfusions or antibiotic treatment (even if the refusal is based on sincere religious convictions), or other now routine procedures for a small child that are clearly medically indicated and required for the maintenance of life, can be overridden, in the United States, by the physician and/or hospital petitioning a court of appropriate jurisdiction for the appointment of a temporary legal guardian (34) who is answerable to that Court.

The unavailability of a parent in a life-threatening circumstance should not preclude therapeutic action. Just as informed consent is imputed or attributed rational behavior to an unconscious accident victim who has a life-threatening condition that requires immediate surgery, such rational behavior can be imputed to the absent parent in the case of an acutely ill neonate. However, in such circumstances if time permits, detailed documentation and consultation with the hospital administration is recommended.

Informed consent in neonatal/perinatal medicine is not an empty gesture to reduce liability, but rather an opportunity for health care providers and parents or guardians to be partners in the decision-making process. Informed consent documents are intended to support decision makers in their choices, rather than merely to provide ratification of medical decisions already made (35). Informed consent documents need to be routinely reviewed to determine that the reading level required to understand them is consistent with the educational, linguistic, and cultural experiences of those being asked to read, understand, and sign or acknowledge the forms (36).

The informed consent process can be extremely complex, with several legal “gray areas.” For example, are maternal rights any more definitive in making critical decisions for a fetus or neonate than paternal rights? Conflicts can arise even when the putative or alleged father is not the legal spouse of the mother. Emergency hearings in front of local judges may be required to resolve conflicting opinions, especially when the decision of one parent may predictably lead, to a medical degree of certainty (more likely than not), significant adverse consequences to the infant. In January 2014, a Texas Court ordered a local hospital to accept that a pregnant mother was brain-dead and that the husband, not the hospital, could decide to end life support (37).

It is one of the ironies of the law, in most states, that an unwed teenage mother has the ultimate legal responsibility for the care of her child, unless the court is petitioned to appoint an alternative guardian. In many states, the live birth of a child, regardless of the age of the mother, results in the mother being declared an

emancipated minor. In contrast, a nonpregnant teenager, living at home and attending high school or college, under the age of majority (usually age 18) may not have the legal right to make decisions about many aspects of her own medical care.

emancipated minor. In contrast, a nonpregnant teenager, living at home and attending high school or college, under the age of majority (usually age 18) may not have the legal right to make decisions about many aspects of her own medical care.

The disclosure of risks in the informed consent process tends to underscore a parent’s sense of helplessness and to portray the physician as somewhat helpless as well. The powerlessness of the parents and their wish that the physician be omnipotent creates unrealistic expectations for the outcomes of procedures and treatment. Gutheil and associates (38) suggest that the physician acknowledge the parent’s wish for certainty and substitute the mystical with a physician-parent alliance in which uncertainty is accepted as an element in medical care.

Advanced Care Planning

Decision making in life and death situations is not easy. Advanced care planning efforts initially evolved in the care of the elderly (39). Advanced care planning, or contingency medical care planning, is no longer generally reserved for adults. The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee of Bioethics developed a policy statement about parental permission and informed consent (40). A distinction is made in this public policy statement and in case law in the United States between emergency medical treatment, life support efforts, and elective surgical procedures, such as circumcision or removing a kidney from one child to aid a sibling (41,42). Neonates need others to make decisions about their treatment and viability. Their treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is rarely a series of leisurely scheduled elective procedures. There must be a designated person with whom the health care providers regularly communicate and who is held to provide consensus about treatment. When potential conflicts in decision making are recognized, a conference among the concerned individuals, with representation from the hospital administration, may be a worthwhile endeavor to clarify who actually has the final decision-making authority. There may be times in the treatment of a patient when one person has to render an immediate decision, even if that decision is not by consensus. Decision-making issues are often confounded when the mother of the neonate is an adolescent herself and not married to the father.

While all 50 states in the United States and the District of Columbia have passed legislation on advance directives, reinforcing the fact that adherence to such directives is mandatory rather than optional continues to be problematic (39). The majority of states place restrictions on proxy decision making. If identification of the responsible party for decision making is not clear or keeps shifting, legal consultation, initiated by the health care providers, is recommended. Most jurisdictions have the ability to hold emergency judicial proceedings when an impasse has been reached and a medical decision must be made before irreversible damage or death occurs (34).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree