Intussusception

Daniel P. Doody

Robert P. Foglia

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114.

Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, Missouri 63110.

Intussusception, the invagination of the intestine into an adjoining intestinal lumen, is among the most common causes of acute abdominal pain in children younger than 5 years of age. It is a disease primarily of infants and toddlers, although intussusception can occur in utero, in neonates, and in adults. Eighty percent to 90% of intussusception cases occur in children between 3 months and 3 years of age.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of intussusception has been ascribed to an inhomogeneity of longitudinal forces along the intestinal wall. In the resting state, normal propulsive forces meet a certain resistance at any point. This stable equilibrium can be disrupted when a portion of the intestine does not appropriately promulgate peristaltic waves. Small perturbations provided by contraction of the circular muscle perpendicular to the axis of longitudinal tension result in a kink in the abnormal portion of the intestine, creating a rotary force (torque). Distortion may continue, in-folding the area of inhomogeneity and eventually capturing the circumference of the small intestine. This invaginated intestine then acts as the apex of the intussusceptum (1).

Intramural, intraluminal, or extramural processes may produce points of disequilibrium. Along with anatomic abnormalities, flaccid areas that follow a paralytic ileus can also create unstable segments because adjoining areas create discordant contractions with the return of bowel activity. Such a model offers an explanation as to the cause of postoperative intussusceptions, which are rarely found to have a surgical lead point, but can complicate any procedures that produce an ileus, including thoracotomies and cardiac procedures.

PATHOLOGY

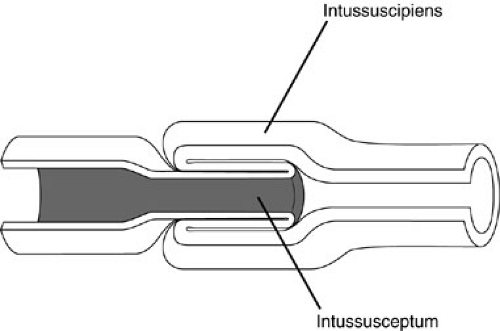

On sectioning, the tumor is composed of the internal layer, the returning middle layer, and the outer ensheathing layer (Fig. 82-1). The entering and returning layers, including the adjacent mesentery, are referred to as the intussusceptum and include any surgical lead point. The receiving or ensheathing layer is referred to as the intussuscipiens. With normal peristalsis, the length of the intussusception increases, and the cycle of venous congestion, lymphatic obstruction, and eventual arterial compromise is initiated. The vascular supply at the apex of the intussusceptum is the most compromised, and the mucosa of the apex experiences secondary sloughing. The combination of mucoid discharge from the bowel and vascular sloughing results in a currant jelly stool.

ETIOLOGY

The most common cause of intussusception is indeterminate and termed idiopathic. In a number of patients, particularly those younger than 3 years of age, there may be enlargement of Peyer’s patch. These children may have had a viral illness as a prodrome 5 to 10 days earlier.

In 2% to 12% of all pediatric cases, the intussusception has an anatomically identifiable lead point. Children with intussusception secondary to surgical lead points usually require operative treatment because the intussusceptum is rarely reduced by pressure reduction. The frequency of lead points as the cause of intussusception increases with age. This is particularly true in children older than 4 years of age, in whom the prevalence of lead points complicating intussusception has been reported to be as high as 57% (2). In adults, the incidence of lead points associated with intussusception is as high as 97% (3). Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common anatomic lead point identified in children. Other anatomic lead points include polyps of

the ileum and colon; benign hamartomas associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; submucosal hematomas associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura; lymphoma; lymphosarcoma; enteric cysts; ectopic, pancreatic, and gastric rests; inverted appendiceal stumps; and anastomotic suture lines. In adults, about one-half of surgical lead points are malignant, and there is a higher incidence of colocolic intussusceptions.

the ileum and colon; benign hamartomas associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; submucosal hematomas associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura; lymphoma; lymphosarcoma; enteric cysts; ectopic, pancreatic, and gastric rests; inverted appendiceal stumps; and anastomotic suture lines. In adults, about one-half of surgical lead points are malignant, and there is a higher incidence of colocolic intussusceptions.

Intussusception is a feature of the gastrointestinal (GI) problems associated with cystic fibrosis (CF) and Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Together, these medical processes account for 3% to 5% of cases of intussusception (4).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Although intussusception can occur at any age, it is convenient from the clinical perspective to divide these patients into those occurring in children younger than 3 years of age and those occurring in older children and adults. In children younger than 5 years of age, intussusception accounts for as many as 25% of abdominal surgical emergencies, exceeding the incidence of appendicitis. Therefore, the practitioner should always consider intussusception in the evaluation of young children and infants who present with acute abdominal pain.

The typical clinical history is that of a 6- to 9-month-old male infant who suddenly cries out, often drawing his or her knees up with the abdominal discomfort. Frequently, the child has emesis and often immediately evacuates. The child may appear diaphoretic during the crisis. The abdominal discomfort appears to last briefly, after which the infant is quiet and may appear well. The incident is repetitive, typically occurring in 15- to 30-minute intervals. As time passes, the child may become increasingly ill with abdominal distention, vomiting, and the eventual appearance of red currant jelly stools seen in approximately 30% of patients. With time, shock intervenes and cardiovascular collapse occurs.

At presentation, the infant is often exhausted and resting quietly. Occasionally and without stimulation, the child may arch and cry out. As the examination begins, the child appears irritable or diaphoretic. Tachycardia or hypotension can be found, even early in the illness, depending on the degree of bowel compromise. Pertinent physical findings are generally confined to the abdomen. A mass may be palpated in the right upper quadrant to midabdomen, but this finding may be difficult to appreciate because of the child’s irritability.

Rarely, a cervixlike mass may be seen protruding through the anus. For prolapse of the intussusception to occur, the mesentery is lax, and the progression of the intussusceptum to the rectosigmoid is rapid. The distinction between intussusception and rectal prolapse, an uncommon finding in infants, can often be made by careful examination of the anal crypts at the dentate line. This anatomic landmark is everted in rectal prolapse, but is not seen with intussusception. An applicator that passes into the space between the apparent prolapse and the anus is also diagnostic of a prolapsed intussusceptum.

Although hematochezia is not always seen with intussusception, 60% to 90% of children with intussusception have gross or occult blood on rectal examination (5). Thirty percent of infants have passed mucoid, bloody stools (red currant jelly stools), and the remaining infants have occult blood on testing.

The differential diagnosis at presentation includes intestinal colic, gastroenteritis, intestinal duplication, appendicitis, incarcerated hernia, and more unusual forms of intestinal obstruction, such as internal hernia and volvulus.

RADIOGRAPHIC DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Early in the course of the illness, supine and upright abdominal films show a normal or nonspecific bowel gas pattern. As the disease progresses, a more obvious pattern of small bowel obstruction with absence of gas in the colon is noted. The most predictive finding of the disease is the presence of a right upper quadrant soft-tissue density, found in 25% to 60% of cases (Fig. 82-2). The absence of bowel gas in the right lower quadrant (Dance’s sign) may be identified in the patient with intussusception. Other radiographic findings include reduced amount of gas in the jejunum, lateralization of the ileum into the right iliac fossa, indiscernible cecal shadow, and reduced amount of feces in the colon (6). Even using these radiographic indicators, 50% to 66% of children who undergo a diagnostic enema for suspected intussusception do not have the disease (7).

Supine cross-table lateral (horizontal-beam) radiographs provide two additional findings that can be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of intussusception (8).

A homogeneous water-density anterior abdominal mass may displace upper abdominal gas inferiorly, or the mass may demonstrate craniocaudal separation into distinct upper and lower bowel gas patterns. One of these two radiographic findings was identified in 75% of intussusceptions in a small series. Other researchers have noted that the intussusceptum may be seen only in this projection and recommend this view as an additional indicator to decide if a diagnostic enema is indicated (9).

A homogeneous water-density anterior abdominal mass may displace upper abdominal gas inferiorly, or the mass may demonstrate craniocaudal separation into distinct upper and lower bowel gas patterns. One of these two radiographic findings was identified in 75% of intussusceptions in a small series. Other researchers have noted that the intussusceptum may be seen only in this projection and recommend this view as an additional indicator to decide if a diagnostic enema is indicated (9).

TREATMENT

Often with a clinically suggestive story and nonspecific findings on plain abdominal radiographs, contrast enemas are performed for diagnosis and therapy. Only in children who have clinical peritonitis or radiographic evidence of perforation is an attempt at pressure reduction absolutely contraindicated. Intravenous access should be obtained prior to a contrast enema. The enema can cause a showering of bacteria into the portal circulator and has approximately a 1% chance of bowel perforation. Patients should receive a broad-spectrum antibiotic to cover enteric organisms prior to the study.

Hydrostatic Reduction

Hydrostatic reduction was proposed by Hirschsprung in 1876 for the treatment of intussusception. The contrast study can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. The use of contrast enemas allows direct visualization of the reduction under fluoroscopic control and is reported to be successful in 65% to 70% of cases. In the hands of an experienced pediatric radiologist, the ratio of successful reduction approaches 85%.

A noninflatable rectal tube is inserted in the rectum, and the buttocks are taped to prevent loss of distending pressure. Contrast enters the rectosigmoid by gravity under fluoroscopic guidance. In the usual case, the contrast column meets a concave filling defect in the transverse colon that can be reduced in a retrograde fashion to the cecum (Fig. 82-3).

A radiographic “rule of threes” applies to hydrostatic reduction in intussusception to minimize the risk of perforation: (1) the barium contrast column should be no greater than 3 ft above the table (100 cm), (2) each attempt should persist until reduction of the intussusceptum fails to progress for a period of 3 to 5 minutes, and (3) a maximum of three attempts should be made. The rule of threes prevents the reduction of necrotic bowel, while optimizing the care of the infant. Experimentally, hydrostatic columns less than 3.5 ft are unable to reduce gangrenous bowel (10). At this height, a 60% weight per volume barium suspension generates an intraluminal

pressure of 120 mm Hg. Dilute water-soluble solutions require a greater height to generate the same intracolonic pressures. A 20% weight per volume meglumine sodium diatrizoate solution (Gastrografin) or 17.2% iothalamate meglumine solution (Cysto-Conray II) achieves an intraluminal pressure of 120 mm Hg at a height of 150 cm (5 ft) (11). Because most intussusceptions are reduced within the first two attempts, successful hydrostatic reduction after three attempts is unlikely (12). The attempted reduction should cease if a progressive reduction of the intussusceptum does not occur after 3 to 5 minutes of constant pressure because the intussusception is unlikely to reduce. In practice, if two attempts at radiographic reduction are not successful, operation is warranted. A radiographic finding often associated with irreducible intussusceptions is the dissection sign, which occurs when barium intercalates between the intussusceptum and the intussuscipiens (13) (Fig. 82-4). Although successful reductions of intussusceptions demonstrating this radiographic finding have been reported (14,15), this feature, coupled with a clinical history greater than 48 hours or radiographic evidence of a complete bowel obstruction, is often associated with intestinal gangrene. Surgery, rather than repeated attempts at hydrostatic reduction, is indicated in this circumstance.

pressure of 120 mm Hg. Dilute water-soluble solutions require a greater height to generate the same intracolonic pressures. A 20% weight per volume meglumine sodium diatrizoate solution (Gastrografin) or 17.2% iothalamate meglumine solution (Cysto-Conray II) achieves an intraluminal pressure of 120 mm Hg at a height of 150 cm (5 ft) (11). Because most intussusceptions are reduced within the first two attempts, successful hydrostatic reduction after three attempts is unlikely (12). The attempted reduction should cease if a progressive reduction of the intussusceptum does not occur after 3 to 5 minutes of constant pressure because the intussusception is unlikely to reduce. In practice, if two attempts at radiographic reduction are not successful, operation is warranted. A radiographic finding often associated with irreducible intussusceptions is the dissection sign, which occurs when barium intercalates between the intussusceptum and the intussuscipiens (13) (Fig. 82-4). Although successful reductions of intussusceptions demonstrating this radiographic finding have been reported (14,15), this feature, coupled with a clinical history greater than 48 hours or radiographic evidence of a complete bowel obstruction, is often associated with intestinal gangrene. Surgery, rather than repeated attempts at hydrostatic reduction, is indicated in this circumstance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree