Intestinal Duplications

John J. Aiken

Department of Surgery/Pediatric Surgery, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53226.

Enteric duplications and mesenteric, omental, and retroperitoneal cysts are rare developmental anomalies that frequently present a diagnostic as well as therapeutic challenge to the clinician and surgeon. These lesions vary greatly in appearance, size, location, and presentation. Although most enteric duplications are symptomatic and present at an early age, some remain undiagnosed into adulthood. These lesions can present with severe and even life-threatening complications, and some have been demonstrated to harbor malignancy. They are frequently misdiagnosed as more common intestinal conditions and are not suspected until encountered intraoperatively. The goals of surgical management are to relieve symptoms, to preserve intestinal function, and to prevent future complications. Due to the potentially complex anatomy and a shared blood supply between intestinal duplications and the native intestine, appropriate management requires familiarity with the anatomic and clinical characteristics of this entity. This chapter reviews the incidence, anatomic location, theories of disordered embryology likely to give rise to these lesions, modes of clinical presentation, and general principles of diagnosis and treatment of intestinal duplications and mesenteric, omental, and retroperitoneal cysts.

INTESTINAL DUPLICATIONS

Intestinal duplications are rare congenital developmental abnormalities that can occur anywhere from the mouth to the anus (1). The first report of an intestinal duplication was by Calder in 1733 (2). The medical literature describes a wide variety of lesions, and the nomenclature includes terms such as enteric cyst, enterogenous cyst, diverticula, giant diverticula, ileum duplex, jejunal duplex, inclusion cyst, unusual Meckel’s diverticula, and others (3). Ladd is credited with unifying the nomenclature in 1937 when he suggested the term duplication of the alimentary tract be used to encompass this constellation of abnormalities (4). Ladd’s inclusive terminology emphasized that these lesions were congenital developmental anomalies that shared several characteristics: (1) the presence of a well-developed smooth muscle component, (2) the epithelial lining represents some portion of the alimentary tract, and (3) most duplications are intimately attached to some portion of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In modern practice, the defining characteristics of intestinal duplications are their location in close proximity to the alimentary tract and a common muscular wall and shared blood supply with the adjacent intestine. The usual location is dorsal to the normal intestine—that is, related to the mesenteric aspect, in contrast to vitelline duct remnants, such as Meckel’s diverticula, which lie on the antimesenteric aspect of the bowel (5). They may be either cystic or tubular in shape. Because these are rare lesions, there are few large patient series reported (Table 85-1) (1,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14). The epithelial lining is variable, but most often reflects the epithelium of the adjacent intestine. Multiple mucosal types have been identified in the same lesion and the presence of heterotopic tissue of diverse origins, including thyroid stroma, lymphoid aggregates resembling Peyer’s patches, ciliated bronchial epithelium, lung tissue, and cartilage, has been reported (3). Communication with the normal GI tract may also occur, although this is not common. A critical feature of as many as one-third of intestinal duplications is the presence of ectopic gastric mucosa, predisposing the cyst to ulceration, bleeding, and perforation if communication with the native bowel exists. In addition, alimentary tract duplications are frequently associated with vertebral abnormalities and other congenital malformations. In 10% to 20% of cases, multiple duplications are present in a single individual. Intestinal duplications are named for the associated GI structures rather than for the type of mucosa lining the cyst. The most common location for an intestinal duplication is the small intestine, in particular, the ileocecal region. Thoracic duplications are the most frequent duplications to be

associated with vertebral abnormalities and may communicate with the spinal canal, or transdiaphragmatically with the abdominal cavity.

associated with vertebral abnormalities and may communicate with the spinal canal, or transdiaphragmatically with the abdominal cavity.

TABLE 85-1 A Summary of Several Reports of Enteric Duplications. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The symptoms and clinical presentation of intestinal duplications vary greatly depending on size, location, presence of gastric mucosa, and communication with the normal bowel. A mass discovered on physical examination or radiographic examination of the chest or abdomen is a common mode of discovery. Specific symptoms are often related to the location of the duplication. Cervical and thoracic duplications may cause respiratory symptoms or dysphagia, or may be an incidental finding on chest radiograph (15,16). Gastric and duodenal duplications may present as a palpable abdominal mass or due to symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction. Pain is the most common symptom and may be caused by distension of the duplication or result from a complication such as intestinal obstruction, peptic ulceration, or perforation. Intestinal obstruction may result from compression of the adjacent bowel lumen or due to the mass effect of the duplication leading to volvulus or intussusception. GI bleeding is also a common complication of enteric duplications. The bleeding can be acute and severe, presenting as hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia, depending on location and magnitude of bleeding. Chronic occult bleeding may present as anemia. The cystic lesions most often do not communicate with the normal intestine. These may achieve a large size and create a mass effect on plain radiographs or be noted as a palpable mass on physical exam. The tubular duplications of the small intestine more frequently communicate with the native bowel and have a high incidence of heterotopic gastric mucosa (17,18). Peptic ulceration can lead to perforation and free intraperitoneal hemorrhage or fistulization into adjacent structures. The majority of alimentary tract duplications that cause clinical symptoms are diagnosed in infancy (greater than 80% before 2 years of age) (19). Older infants and children with intestinal duplications may experience indolent and vague abdominal complaints over prolonged periods or intermittent GI bleeding and anemia. Colonic or presacral duplications typically present due to obstruction, constipation, or prolapse through the anus. Enteric duplications are frequently associated with vertebral abnormalities such as spina bifida or missing, fused, or hemivertebrae. Rarely, there may be an intraspinal component causing neurologic symptoms from spinal cord compression. Myelomeningocele is associated with some enteric duplications, especially in the thoracic cavity. Some duplications remain silent and persist into adulthood (20). Neoplastic changes have been reported in duplications diagnosed in adulthood—most in duplications of the colon and rectum (21,22). Hindgut duplications may be associated with splitting of the lower vertebrae and sacrum and severe urogenital abnormalities, such as doubling of the external genitalia or other perineal abnormality.

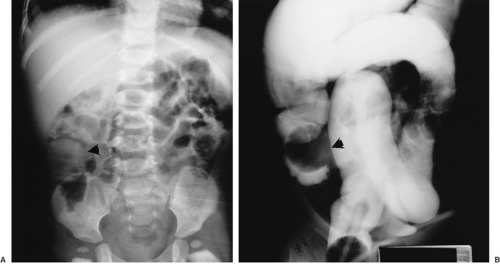

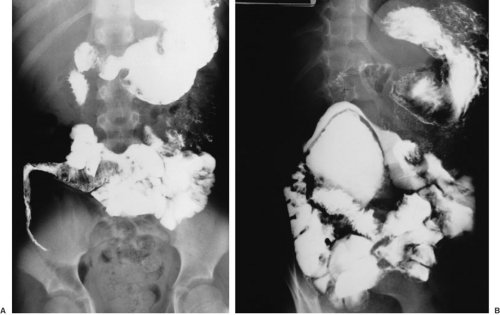

Intestinal duplications are often difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Common intestinal conditions, such as appendicitis, pyloric stenosis, intussusception, or malrotation, are frequent misdiagnoses when the duplication is found at laparotomy. In cases of large lesions, the diagnosis may be suspected by the finding on plain radiographs of a chest or abdominal mass with displacement of adjacent structures. This finding in the abdomen may prompt GI contrast studies, which may demonstrate the impression of a mass lesion on normal bowel (Fig. 85-1) and possibly communication with the lumen of the native bowel (Fig. 85-2), which is diagnostic of an intestinal duplication. Ultrasound has proven to be an excellent diagnostic modality

for enteric duplications, and the classic triple-layer image (Fig. 85-3) is pathoneumonic of intestinal duplications (23). Ultrasound is also useful to evaluate for possible associated genitourinary anomalies in cases of hindgut duplications and should be done routinely. Thoracic duplications are often apparent on routine chest radiography. Axial imaging with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also good tests to demonstrate thoracic duplication cysts and their relationship to adjacent structures, and are particularly helpful in evaluating for possible associated vertebral abnormalities or central nervous system (CNS) lesions. In cases that present with GI bleeding, radionuclide technetium scanning can be very helpful in diagnosing and localizing duplications in the thorax, small bowel, and hindgut (24). Enteric duplications have been diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound examinations (25).

for enteric duplications, and the classic triple-layer image (Fig. 85-3) is pathoneumonic of intestinal duplications (23). Ultrasound is also useful to evaluate for possible associated genitourinary anomalies in cases of hindgut duplications and should be done routinely. Thoracic duplications are often apparent on routine chest radiography. Axial imaging with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also good tests to demonstrate thoracic duplication cysts and their relationship to adjacent structures, and are particularly helpful in evaluating for possible associated vertebral abnormalities or central nervous system (CNS) lesions. In cases that present with GI bleeding, radionuclide technetium scanning can be very helpful in diagnosing and localizing duplications in the thorax, small bowel, and hindgut (24). Enteric duplications have been diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound examinations (25).

FIGURE 85-3. Ultrasound study of a patient with gastric duplication demonstrating the classic findings of triple layering. |

Duplications in the pediatric population are benign lesions, and therefore, the surgical therapy should aim primarily to eliminate symptoms, preserve function, and prevent future complications and recurrence. There have been a small number of case reports of an intestinal duplication harboring malignancy, almost exclusively adenocarcinoma in adult patients (16). Mortality due to bleeding or sepsis from perforation is related to delay in diagnosis and definitive treatment. Although some of these lesions are technically challenging, morbidity and mortality should be rare in modern practice.

INCIDENCE

Enteric duplications are rare lesions and their exact incidence is difficult to determine. They are reported in 1 of every 4,500 autopsies (26). They appear to be most often seen in white males; the exception being complex hindgut duplications, which are more common in females. There does not appear to be a familial incidence. Alimentary tract duplications are most commonly located in the small intestine and mediastinum (posterior), whereas rectal, duodenal, gastric, and thoracoabdominal locations are extremely rare. Synchronous duplications are reported in as many as 15% of patients.

ASSOCIATED ANOMALIES

Associated anomalies are common with alimentary tract duplications. Most important is an association between thoracic and thoracoabdominal duplications and vertebral anomalies, such as missing, bifid, or fused vertebrae (12,27). Esophageal duplications are seen in association with other esophageal malformations, such as esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, and pulmonary agenesis. Small intestine cystic duplications have been reported with coexisting intestinal atresias and malrotation (11,13). Tubular hindgut duplications are an extremely complex and diverse group of anomalies frequently associated with genitourinary and other severe malformations (28,29).

EMBRYOLOGY

The embryogenesis of intestinal duplications is not known. There are many theories, but none adequately explains the origin of all lesions in this diverse constellation of anomalies, suggesting that more than one pathogenic possibility may be necessary to explain the anatomic variability. The following is a brief discussion of the more common theories of disordered embryogenesis resulting in intestinal duplications.

Split Notochord Theory

Bentley and Smith proposed the “split notochord syndrome” in an attempt to explain the frequent association between developmental anomalies of the skin, spine, CNS, and the GI tract (30). The dorsal location and relatively frequent (15%) association of enteric duplications with vertebral abnormalities provide support for this theory. The

notochord is formed during the third week of the gestation when a proliferation of cells from the primitive streak of the ectoderm develops as a midline structure separating the lining of the yolk sac (primitive endoderm) from the lining of the amniotic cavity (primitive ectoderm). A transient opening, the neurenteric canal, appears and connects the neural ectoderm with the GI endoderm. The notochord is at first in intimate association with the endodermal cells, but normally it later migrates and separates from them as part of the process of cephalic growth of the ectoderm and notochord mesoderm. Persistence of the neurenteric canal causes the notocord to split as it migrates, resulting in the development of spina bifida or other vertebral anomalies and anterior and posterior meningomyelocele. If the notochord fails to detach from the endoderm, adherent endodermal cells may be pulled anterior and cephalad as the tissues separate. These endodermal cells, detached from the roof of the developing gut, may form an intestinal duplication. If they remain attached to the notochord, they may also act as a local barrier to the later fusion of the vertebral mesoderm, resulting in vertebral abnormalities. Beardmore and Wigglesworth (31) proposed that there was adherence of the ectoderm and endoderm in the neural plate that caused the notochord to “split” as it grew. The splitting of the notochord by the persistent neurenteric canal as it migrates may result in a vertebral anomaly (Fig. 85-4). The resulting tubular structure may extend through the diaphragm, connecting abdominal viscera to the thoracic or cervical spine. If the connection is lost, an isolated mediastinal duplication or an intramesenteric abdominal diverticulum may result, and the vertebral anomaly may resolve. Failure of regression of the neurenteric canal and persistent attachment to the notochord may prevent closing of the vertebral bodies, resulting in a spectrum of neurenteric pathology, including occult anterior spina bifida, intraspinal enteric cyst, dorsal enteric sinus, neurenteric cyst, diastematomyelia, or a complete dorsal enteric fistula. The absence of spinal defects in many alimentary tract duplications makes the split notochord theory less tenable as a unifying model of origin for alimentary tract duplications (32).

notochord is formed during the third week of the gestation when a proliferation of cells from the primitive streak of the ectoderm develops as a midline structure separating the lining of the yolk sac (primitive endoderm) from the lining of the amniotic cavity (primitive ectoderm). A transient opening, the neurenteric canal, appears and connects the neural ectoderm with the GI endoderm. The notochord is at first in intimate association with the endodermal cells, but normally it later migrates and separates from them as part of the process of cephalic growth of the ectoderm and notochord mesoderm. Persistence of the neurenteric canal causes the notocord to split as it migrates, resulting in the development of spina bifida or other vertebral anomalies and anterior and posterior meningomyelocele. If the notochord fails to detach from the endoderm, adherent endodermal cells may be pulled anterior and cephalad as the tissues separate. These endodermal cells, detached from the roof of the developing gut, may form an intestinal duplication. If they remain attached to the notochord, they may also act as a local barrier to the later fusion of the vertebral mesoderm, resulting in vertebral abnormalities. Beardmore and Wigglesworth (31) proposed that there was adherence of the ectoderm and endoderm in the neural plate that caused the notochord to “split” as it grew. The splitting of the notochord by the persistent neurenteric canal as it migrates may result in a vertebral anomaly (Fig. 85-4). The resulting tubular structure may extend through the diaphragm, connecting abdominal viscera to the thoracic or cervical spine. If the connection is lost, an isolated mediastinal duplication or an intramesenteric abdominal diverticulum may result, and the vertebral anomaly may resolve. Failure of regression of the neurenteric canal and persistent attachment to the notochord may prevent closing of the vertebral bodies, resulting in a spectrum of neurenteric pathology, including occult anterior spina bifida, intraspinal enteric cyst, dorsal enteric sinus, neurenteric cyst, diastematomyelia, or a complete dorsal enteric fistula. The absence of spinal defects in many alimentary tract duplications makes the split notochord theory less tenable as a unifying model of origin for alimentary tract duplications (32).

A second theory suggests that failure of the normal regression of embryonic diverticula may occur. Diverticula are common in the developing human GI tract (33). Their finding at numerous sites around the circumference of the gut wall provides a potential explanation for small cystic duplications noted in the intestinal wall, and for enteric cysts located in the presacral space. However, this theory does not explain the propensity for the location of enteric cysts within the leaves of the bowel mesentery, or the finding of multiple types of mucosa lining the wall of some enteric duplications.

The theory of median septum formation suggests that the walls of adjacent fetal bowel may be flattened by extrinsic compression with subsequent adherence and fusion resulting in doubling of the lumen. Although this would explain the occurrence of adjacent or side-by-side tubular duplications, there is no embryonic evidence for this theory.

The association of complex tubular duplications of the colon and rectum with urogenital anomalies and doubling of other body parts may best be explained by the theory of partial or abortive twinning (5,9,28,29,34,35,36,37,38). This theory suggests that the axial structures in hindgut duplications are “twinned” because of a split in the primitive streak, resulting in two notochords, separated at their caudal ends, which later fuse during cranial elongation of the embryo. This would result in the duplication of structures derived from the hindgut, including distal ileum, colon, rectum, and anus. With this anomaly, doubling of the genitalia and of the bladder and urethra, exstrophy of the bladder, spina bifida, omphalocele, and other lesions are observed with extraordinary frequency. It is speculated that twinning early in the hindgut’s caudal growth may result in duplication of other pelvic organs, including genital structures, whereas later twinning may result only in colorectal duplication. Doubling of the anus, vagina, bladder, lower trunk, and extremities (dipygus) all have been described and can be associated with rare cases of double spines and two heads.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree