Inguinal Hernia Reduction

Sharon R. Smith

Introduction

Two common causes of scrotal swelling in children are inguinal hernia and hydrocele. Inguinal hernias, which are classified as direct or indirect, occur when abdominal contents are present within a patent processus vaginalis. With an indirect inguinal hernia, the most common type in children, abdominal contents pass through the internal inguinal ring, whereas with a direct inguinal hernia, abdominal contents pass through the external inguinal ring. Direct inguinal hernias are rare in children and often occur after an indirect inguinal hernia repair (1).

The incidence of inguinal hernias in children ranges from 0.8% to 4.4% (1) and is highest in premature infants (16% to 25%). About one third of inguinal hernias occur in children under 6 months of age (1,2), with a peak incidence during the first 3 months of life. Inguinal hernias are six times more common in boys than girls and are more common on the right side (60% right, 30% left, 10% bilateral) (3).

A hydrocele develops if peritoneal fluid fills the processus vaginalis. It may occur along the spermatic cord or within the scrotal sac itself. Hydroceles are usually present at birth and often are bilateral; however, noticeable scrotal swelling may not develop until later in childhood. The hydrocele may decrease in size during sleep or when the child is relaxed. A hydrocele generally requires no acute treatment but can pose a clinical challenge when it must be distinguished from an inguinal hernia.

An incarcerated inguinal hernia occurs when the abdominal contents cannot be easily reduced into the abdominal cavity. Incarcerations occur more frequently in girls, in premature infants, and during the first year of life. In girls, the hernia sac may contain the fallopian tube, ovary, or uterus (1,4,5,6,7,8,9). A strangulated hernia compresses structures passing through the inguinal canal, such as viscera and blood vessels. Vascular compromise can lead to necrosis of the viscera and perforation of herniated intestine (1). Unlike adults, most children with irreducible incarcerated hernias rapidly progress to strangulation. Injury can occur to the testes, spermatic cord, or ovaries. Prompt reduction of the inguinal hernia before ischemia develops is the main goal of management.

Anatomy and Physiology

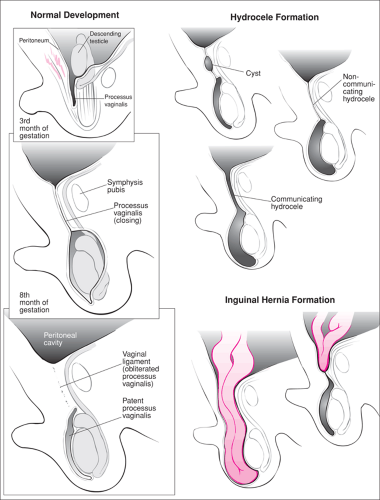

The processus vaginalis is an outpouching of the peritoneum that develops approximately 3 months before birth. It descends through the inguinal canal into the scrotum or the labia. In boys, the testes descend with the processus and enter the scrotal sac between the seventh and ninth months of gestation (10). In girls, the processus ends in the labia majora. Normally, the processus vaginalis obliterates spontaneously after birth. When it does not obliterate, a patent processus vaginalis is created. Patency may remain in as many as 20% of normal adults (11). It is estimated that 80% to 94% of infants have patency of the processus at birth (1).

The partial or complete failure of the obliteration of the processus vaginalis predisposes to the formation of indirect inguinal hernias and hydroceles (Fig. 87.1). The processus vaginalis may remain widely patent, resulting in a scrotal hernia (complete inguinal hernia). A communicating hydrocele may develop when the proximal processus vaginalis remains patent but the neck of the communication is quite narrow. This allows peritoneal fluid to enter and exit the scrotal sac, although the patent neck is not large enough to allow entry of abdominal viscera. The processus may obliterate distally, leaving a patent proximal sac and the potential for an inguinal hernia. A commonly observed type of isolated hydrocele (noncommunicating hydrocele) occurs when fluid collects within the tunica vaginalis, and the inguinal processus obliterates

proximally. A hydrocele of the cord occurs when the processus closes irregularly, leaving a patency and fluid collection isolated to the cord (12).

proximally. A hydrocele of the cord occurs when the processus closes irregularly, leaving a patency and fluid collection isolated to the cord (12).

TABLE 87.1 Conditions Associated with Inguinal Hernia | |

|---|---|

|

As mentioned previously, incarceration of a hernia rapidly progresses to strangulation in children. A strangulated hernia occurs when an incarcerated bowel or solid organ infarcts and becomes necrotic. This results from the following sequence of events: (a) pressure on the abdominal contents passing through the inguinal canal causes decreased lymphatic and venous drainage, (b) worsening edema of the surrounding tissues causes further compression, and (c) the pressure eventually becomes sufficient to prevent arterial blood flow.

Several conditions predispose children to develop inguinal hernias (Table 87.1), although most occur in healthy children. Those with connective tissue disorders such as Hunter-Hurler, Ehlers-Danlos, and Marfan syndromes have frequent hernias. Thirty-six percent of patients with Hunter-Hurler syndrome developed inguinal hernias in one study (13). Inguinal hernias also occur in 6% to 15% of children with cystic fibrosis (14). Most of the predisposing conditions increase intra-abdominal pressure or fluid, cause abdominal wall defects, or otherwise prevent the processus vaginalis from closing normally.

Indications

Inguinal hernias appear as a bulge in the inguinal, scrotal, or labial region and are often more apparent when a child is crying or straining (15,16). Parents may report seeing a lump or bulge that reduced spontaneously or that the parent manually reduced. When a child presents with such a history, the clinician must look for corroborative physical findings. Spermatic cord thickening, caused by the presence of a hernia sac, can be often be appreciated by rolling the proximal cord between the thumb and index finger. Another suggestive finding, the “silk glove” sign, is detected by rubbing the index finger over the spermatic cord at the pubic tubercle. The two layers of a hernia sac rubbing together are said to feel like rubbing two layers of silk cloth together. Neither of these signs is pathognomonic for a hernia but may be helpful in arriving at the diagnosis (17). A quiet infant will usually strain the abdominal muscles if stretched supine with legs extended and arms held straight above the head. Most infants struggle to get free, increasing intra-abdominal pressure and often causing the inguinal hernia to protrude. Older children may increase intra-abdominal pressure with a Valsalva maneuver such as blowing up a balloon or coughing while standing.

Children with incarcerated inguinal hernias often present with crying, irritability, and vomiting. The hernia will be tender to palpation and may be associated with scrotal edema and/or abdominal distention. Bowel obstruction can occur if the hernia is not reduced quickly. Strangulation should be suspected when the child has a fever, bloody stools, testicular swelling in addition to scrotal swelling, leukocytosis, or an inflamed scrotum or inguinal canal. The total time of incarceration is thought by most experts to be an unreliable predictor of bowel strangulation (18).

As mentioned previously, differentiating a hydrocele from an inguinal hernia is sometimes difficult. Although hydroceles are often described as inguinal masses that can be transilluminated, bowel will also transilluminate, and an incarcerated hernia cannot be ruled out based on this characteristic (19). A hydrocele usually has a definite upper limit and never extends into the internal ring of the inguinal canal. Additionally, a hydrocele is generally movable, smooth, and nontender and feels cystic. A rectal examination can sometimes help confirm an inguinal hernia by palpation of the bowel as it enters the internal ring of the inguinal canal. Listening for bowel sounds over the scrotum may also be helpful. However, it should be noted that a hydrocele of the cord can be clinically indistinguishable from an incarcerated inguinal hernia (10).

Acute scrotal and inguinal swelling includes a myriad of diagnostic possibilities (Table 87.2). One important diagnosis on this list that must be distinguished from an inguinal hernia is testicular torsion. Boys with testicular torsion typically have acute onset of painful scrotal swelling, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The testicle is exquisitely tender, but the tenderness does not usually extend to the external ring of the inguinal canal. There is often loss of the cremasteric reflex; however, this reflex may be absent in some patients with inguinal hernias (20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree