Hypospadias

David Pinkstaff

John Noseworthy

Department of Urology, Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, Jacksonville, Florida 32244.

Mayo Medical School, Thomas Jefferson University, Nemours Foundation, Jacksonville, Florida 32246.

DEFINITION AND TERMINOLOGY

Hypospadias is defined as a developmental anomaly characterized by a defect in the wall of the urethra so the (urethral) canal is open for a greater or lesser distance on the undersurface of the penis. It also applies to a condition in the female in which the urethra opens into the vagina. It is derived from the Greek word meaning “to draw away from under or having the orifice of the penis too low” (1). The following discussion focuses on the condition in the male and will not discuss female hypospadias.

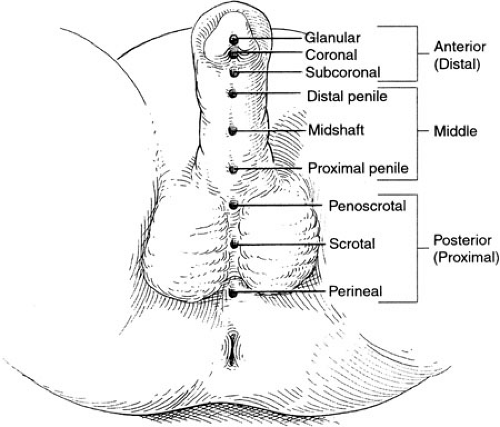

A spectrum of severity of hypospadias exists, ranging from minor abnormalities involving the position of the urethral meatus on the proximal portion of the glans penis to severe forms in which the urethra opens in the peroneum just anterior to the anus. Classifications of severity separating the various forms of hypospadias into first degree, second degree, and third degree have been employed, but such general categories tend to obscure rather then illuminate the spectrum. More apropos is the descriptive terminology that is in wide use today. In this system of classification, the location of the hypospadias defect is described. Glanular hypospadias, proximal glanular hypospadias, coronoglanular hypospadias, subcoronal hypospadias, distal shaft hypospadias, midshaft hypospadias, proximal shaft hypospadias, penoscrotal hypospadias, scrotal hypospadias, and perineal hypospadias are all terms that have been used to more precisely characterize and categorize the degree of severity of the urethral abnormality (Fig. 99-1). Using such descriptive classification avoids ambiguity, imprecision, and the need for translation of such terms as third-degree hypospadias into a more anatomically accurate and consistent category. Precision in classification is important because the severity of the defect dictates the complexity of the repair and aids in clarifying the need for surgical intervention with the patients’ parents. Also, it allows a more accurate comparison between analyses of outcomes in treatment of the disorder. As described in this chapter, the results of surgical repair of hypospadias, the occurrence of complications, the effort and time involved in caring for these children, and the expectations of the parents varies in a stepwise, linear fashion with increasing degrees of severity. Thus, accurate descriptions of the defect are important from the very outset of evaluation.

Two additional descriptive factors add meaning to the evaluation of hypospadias. The first involves the presence or absence of chordee. As applied to hypospadias, chordee is defined as “the ventral curvature of the penis, most apparent on erection, due to congenital shortness of the urethra and on rare occasions in patients with a normally situated meatus” (1). In the field of hypospadiology, chordee is also the term for the dense, scarlike tissue present to a variable degree around and adjacent to the hypospadic urethra, which produces restriction and “bow stringing” of the penile shaft, limiting full, straight extension of the phallus during erection. Chordee is usually present to one degree or another with those forms of hypospadias involving the penile shaft and more proximal (and thus more severe) forms. Hypospadias may occur in the absence of chordee, but this is unusual. Each patient presenting with hypospadias must be carefully examined for chordee and an accurate estimate made preoperatively to include the surgical treatment of chordee in the preoperative planning and in the discussion with the parents.

An accurate assessment of the extent of chordee may not be possible until the child is examined under anesthesia at the time of surgery. The use of an artificial erection, created by the injection of sterile saline and/or heparinized sterile saline into the erectile tissue may be the most accurate method of demonstrating the true extent of chordee (2).

Chordee can occur without hypospadias. In this circumstance, the chordee tissue may create significant curvature of the penis in erection despite a normally

positioned urethral meatus. Correction of “chordee without hypospadias” may necessitate division of the foreshortened urethra and lengthening it with an interposition urethroplasty.

positioned urethral meatus. Correction of “chordee without hypospadias” may necessitate division of the foreshortened urethra and lengthening it with an interposition urethroplasty.

The second, additional element of hypospadias evaluation is an assessment of the quality of the distal hypospadic urethra, particularly with regard to the degree of associated deficiency of the corpus spongiosum because this is often significantly deficient for a variable length. This aspect of evaluation may be deferred until the operation has begun; however, some approximation of this associated defect is important preoperatively to allow a full discussion with the parents regarding the potential surgical options and the extent of the operation that may be necessary to repair the defect.

EMBRYOLOGY

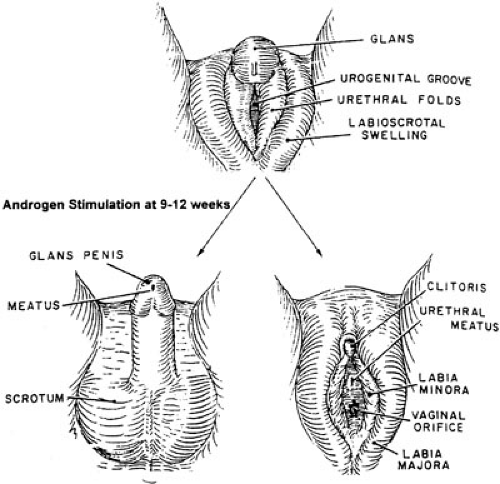

Fetal external genitalia are initially indifferent and are programmed to develop the female phenotype unless androgen stimulation occurs. The indifferent genital tubercle becomes evident at about 6 weeks’ gestation. Outgrowth of endodermal cells from the walls of the cloaca and urogenital sinus along the ventral midline surface of the tubercle forms the urethral plate (3). Mesodermal proliferation on either side of the plate creates urethral folds. Around 8 weeks, the superficial layer of cells within the plate dies, forming the urethral groove (Fig. 99-2).

The interstitial (Leydig) cells of the testis increase in number, size, and function between the ninth and twelfth weeks of development. Testosterone stimulation induces the urethral folds to begin fusing ventrally in the midline to create the urethra. This process begins proximally and continues to the level of the glans penis. The glanular urethra distal to the fossa navicularis, however, is formed by ingrowth of surface epithelium (ectoderm), which invaginates through the glans to meet the more proximal urethra. The epithelium becomes stratified squamous epithelium at the completion of development. The classic “ectodermal

ingrowth theory” has more recently been challenged by the “endodermal differentiation theory.” Immunohistologic studies by Kurzrock and associates (4) suggest that the entire male urethra, including the glanular portion, forms by tubularization of the urethral plate. Cell differentiation rather than ectodermal ingrowth is responsible for the stratified squamous epithelium of the distal glanular urethra.

ingrowth theory” has more recently been challenged by the “endodermal differentiation theory.” Immunohistologic studies by Kurzrock and associates (4) suggest that the entire male urethra, including the glanular portion, forms by tubularization of the urethral plate. Cell differentiation rather than ectodermal ingrowth is responsible for the stratified squamous epithelium of the distal glanular urethra.

Mesenchymal tissue of the urethral folds differentiates into corpus spongiosum, which fuses with the glans, completely surrounding the urethra. The dorsal and ventral aspects of both the preputial skin and the corpora cavernosa have been found to have different growth rates. As a result, significant ventral curvature exists in the developing phallus (5,6). The dorsal ectodermal tissue of the prepuce proliferates at a faster rate than the mesoderm forming the corpora cavernosa. Thus, folds of skin extend over the glans. Hunter noted that the prepuce does not uniformly surround the glans during penile development (6). The skin travels obliquely on either side of the penis back to the urethral opening ventrally. As the urethra tubularizes distally, the ventral extensions fuse in the midline and create the frenulum. Complete preputial covering of the glans occurs at approximately the twentieth week of development (7).

Arrest of urethral formation at any time during development results in hypospadias. The urethral meatus can be located anywhere on the ventral midline from the perineum to the glans as shown in Fig. 99-1. The urethral plate extends from the urethral opening to the tip of the glans. The appearance of the plate will depend on the extent of development of the urethral groove. It may appear as a flat surface or deep cleft.

The ventral glans does not fuse in the midline in hypospadias. Also, the corpus spongiosum usually does not cover the ventral aspect of the most distally formed portion of the urethra and diverges laterally to join the glans “wings.” In most cases of hypospadias, the prepuce is only a dorsal hood, reflecting developmental arrest prior to ventral fusion and formation of the frenulum. Ventral angulation, called chordee, may persist as another indicator of arrested penile development.

INCIDENCE

Various reports have estimated the incidence of hypospadias between 1 and 10 per 1,000 live births. This range presumably reflects variation in the severity of the defects reported. Some series may exclude the less severe glanular forms and thus not include all types of the defect. An incidence of 1 per 100 to 150 live births is frequently cited and appears reasonably accurate (8). This is helpful in discussions with parents because it gives them an appreciation that this congenital abnormality is not particularly uncommon and that it can be dealt with successfully.

Thus, a children’s health care center serving a combined obstetrical experience of 20,000 births per year might well see on the average 100 patients with hypospadias annually. The 20-year experience reported by Gross in his classic textbook The Surgery of Infancy and Childhood (9) included 392 patients with hypospadias. One hundred of these patients were classified as penoscrotal or perineal, 32 in the shaft, and 260 as frenular (distal, less severe).

ASSOCIATED ANOMALIES

Cryptorchidism and Inguinal Hernia

Both hypospadias and cryptorchidism may be the result of androgen deficiency. A coexisting undescended testicle has been noted in 8% to 9% of boys with hypospadias. The incidence varies with the severity of the hypospadias defect, and males with more proximal lesions have a significantly increased rate of cryptorchidism. Inguinal hernia and/or hydrocele has been an associated finding in up to 10% of cases (10).

Prostatic Utricle

This structure is the remnant of the fused caudal ends of the paramesonephric ducts. Enlargement of the utricle can be seen in boys with hypospadias. Devine et al. reported enlargement of the prostatic utricle in 10% of boys with penoscrotal and 57% with perineal hypospadias. This may result from delayed or inadequate secretion of müllerian inhibiting factor or incomplete masculinization of the urogenital sinus (11). Stasis of urine in the utricle may be a rare cause of urinary tract infection or even stone formation (12). Usually, however, there is no clinical significance except that it may complicate catheterization during hypospadias repair.

Syndromes

There are 49 syndromes described in which hypospadias is an associated finding (13). The Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome includes multiple congenital anomalies due to a deficiency of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase causing impaired cholesterol synthesis. This condition has an incidence of 1 in 20,000 births and is the third most prevalent autosomal-recessive inherited condition in whites. Manifestations include mental retardation, small stature, facial deformities, syndactyly of the second and third toes, and male genital anomalies. External genital findings can range from hypospadias in approximately 70% of cases to micropenis to female phenotype (14).

The Opitz-Frias syndrome is characterized by hypertelorism and hypospadias. Additional findings include mild to moderate mental retardation and swallowing

difficulties resulting in aspiration. Inheritance includes both X-linked and autosomal-dominant forms that have similar clinical manifestations. Cryptorchidism is frequently seen in these patients as well.

difficulties resulting in aspiration. Inheritance includes both X-linked and autosomal-dominant forms that have similar clinical manifestations. Cryptorchidism is frequently seen in these patients as well.

Trisomy 13 (Patau’s syndrome) and trisomy 18 (Edwards’ syndrome) are severe genetic conditions that are usually fatal within the first few years of life. Cryptorchidism is noted in at least 50% of each of these populations. Hypospadias is seen in less than 50% of patients with trisomy 13 and less than 10% of boys with trisomy 18.

Intersex States

Isolated hypospadias on the shaft of a normal-size phallus and two palpable gonads should not raise concern for an intersex disorder. A meatus positioned in the scrotum or perineum increases the likelihood of intersexuality. A high index of suspicion for an intersex state should be maintained for infants with any degree of hypospadias associated with cryptorchidism.

Kaefer et al. evaluated 79 presumed males with hypospadias and unilateral or bilateral cryptorchidism (15). Intersex conditions were identified in 30% of 44 patients with unilateral and 32% of 35 patients with bilateral undescended testes. Patients with one or more nonpalpable testes were approximately three times more likely to have an intersex state (with an incidence of 47% to 50%) than patients with palpable undescended gonads. In addition, a more posterior meatal position was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of intersex.

A newborn with hypospadias and bilateral nonpalpable testes must be evaluated for female pseudohermaphroditism. Male pseudohermaphroditism should be considered with scrotal or perineal hypospadias with palpable gonads or after the adrenogenital syndrome has been ruled out in newborns with nonpalpable testes. True hermaphroditism may present with asymmetric gonadal descent and hypospadias. Patients with mixed gonadal dysgenesis have unilateral cryptorchidism, representing the dysgenetic streak gonad, and often have a small phallus.

EVALUATION

Routine imaging of the urinary tract with ultrasonography or intravenous urography is not required in children with isolated anterior or middle ureteral hypospadias. Radiologic studies are only obtained in boys who develop urinary tract infection or whose hypospadias is part of a malformation syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree