Gastrostomy Tube Replacement

John W. Graneto

Introduction

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement was introduced in 1980 in Cleveland, Ohio, as a procedure for children who required long-term nutritional support (1,2). The endoscopically placed PEG tube was found to be simpler and safer than surgical gastrostomy tube placement (3). It quickly became popular as a method of providing enteral access for children suffering from chronic illnesses that lead to impaired and insufficient oral intake, the most common being anoxic brain injury (3). Nutritional support and medication administration—either long term or for brief periods postoperatively—are easily achieved in these patients with a PEG tube. The increasing frequency with which these tubes are being used in pediatric patients, combined with the tendency of the tubes to dislodge or malfunction, make replacement of gastrostomy tubes a common procedure for the emergency physician.

Anatomy and Physiology

Children can have impaired swallowing function for a variety of reasons, including anoxic brain injury, gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal injury from lye ingestion, congenital esophageal anomalies (e.g., stenosis, stricture, duplication, tracheoesophageal fistula), achalasia, familial dysautonomia, and any disease that interferes with oropharyngeal muscle tone and coordination (e.g., muscular dystrophy, Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, myasthenia gravis). These children may be unable to achieve sufficient oral intake to prevent eventual dehydration, or they may have such uncoordinated swallowing reflexes that they are highly prone to aspirate orally ingested substances into the lungs. Using a PEG tube avoids these problems by allowing direct access to the stomach, obviating the need for oral administration of medications and feedings.

The anterior or anterolateral surface of the stomach wall is the usual site of insertion of a PEG tube. The PEG site stoma traverses the stomach wall beginning at the internal mucosa and extending outward to the visceral lining, fixes these layers to the parietal peritoneal lining of the abdominal wall, and finally emerges through the skin surface externally. After several weeks, a fistulous tract forms, and adherence of these layers to each other becomes permanent.

Indications

PEG tubes require replacement for several reasons. Tubes can deteriorate over time and become dysfunctional during the natural course of their use (4). PEG tubes also can become blocked, usually because of formula accumulations that dry and solidify. Certain formulas (Ensure, Pulmocare, and Osmolite) are more prone to clogging than others when exposed to acidic stomach contents (5). Tubes also can become blocked because of mechanical twisting, kinking, and undissolved medications. In general, attempts to unstop these types of blockages should not be made with stylets or other probing devices, as these efforts can potentially rupture the feeding tube below the skin surface, leading to intra-abdominal leakage. A blocked tube that cannot be made functional should be removed and replaced. Attempts to remove a well-positioned yet malfunctioning tube should be made only after assurance that the replacement equipment and personnel to perform the replacement are readily available.

Active children may cause their PEG tubes to become accidentally dislodged from the stomach. Although the specific incidence of this event is not known, it is likely a relatively frequent occurrence. Inadvertent dislodgement of a PEG tube

requires timely tube replacement, because the stoma site will begin to close over in a short time (usually within hours). Furthermore, delays in tube replacement will increase the difficulty of passing a temporizing device such as a Foley catheter (6). If a Foley catheter is placed promptly, replacement of the PEG tube can usually be accomplished in the emergency department (ED) or office setting without requiring anesthesia or intervention by a subspecialist.

requires timely tube replacement, because the stoma site will begin to close over in a short time (usually within hours). Furthermore, delays in tube replacement will increase the difficulty of passing a temporizing device such as a Foley catheter (6). If a Foley catheter is placed promptly, replacement of the PEG tube can usually be accomplished in the emergency department (ED) or office setting without requiring anesthesia or intervention by a subspecialist.

Immediate Postoperative Period

Although PEG tube replacement is usually a simple procedure, spontaneous expulsion of a tube that was recently placed (within 1 to 2 weeks of the initial operative procedure) is a special case. In such situations, the stomach wall may not have had time to adhere to the peritoneal lining and overlying skin. Attempts at re-establishing a PEG tube or temporizing with a Foley catheter can disrupt the fistula tract, resulting in the formation of a false lumen into the peritoneum. Instillation of formula through the improperly positioned tube can cause a chemical and bacterial peritonitis, with potentially life-threatening consequences. Therefore, patients requiring PEG tube replacement in the immediate postoperative period should have consultation from the ED with the surgeon, gastroenterologist, or interventional radiologist who originally placed the tube.

Equipment

Replacement tube

Lubricant (e.g., K-Y Jelly, viscous lidocaine)

10-mL syringe

30- to 60-mL syringe

Stethoscope

Tape

Benzoin

Absorbent dressing

Replacing a gastrostomy tube in the ED does not necessarily mean that the dislodged tube must be replaced with the same type of tube. If the original type of tube is available, however, this is preferred. Additionally, a replacement tube that is the same size as the original should be used when possible. Usual catheter sizes range from 18 to 28 Fr.

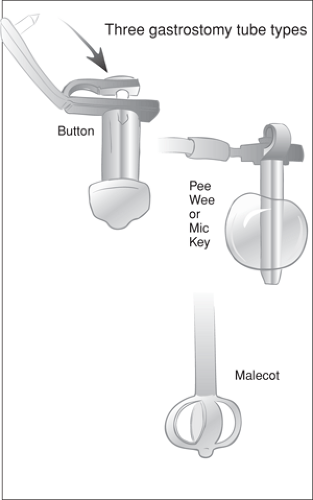

A variety of PEG tubes are currently available on the market, most of which are made of silicone, rubber, or polyurethane. Many tubes are similar, with only minor differences in their design, connectors, and lengths (Fig. 85.1). The more common types are (a) balloon-ended, such as the MIC-KEY (Kimberly Clark, Roswell, GA); (b) mushroom-shaped (dePezzer), such as the Button (BARD Peripheral Vascular, Tempe, AZ); and (c) with collapsible wings, such as the Malecot.

The Button was first developed in 1984 (7). Its advantages over conventional gastrostomy tubes include less skin irritation, fewer problems with migration and dislodgment, and no awkward lengthy tube exposed externally. The Button tube does not have to be changed as frequently as other devices (8,9,10). The Button has gained popularity and is favored by both patients and families.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree