Herpes simplex virus (HSV) esophagitis occurs primarily in immunocompromised patients, who may have life-threatening disease at the time of diagnosis.2 In immunocompetent patients, the infection is self-limited and resolves spontaneously in 1 to 2 weeks.3 Concomitant herpes labialis or oropharyngeal ulcers may be present. Symptoms include odynophagia, dysphagia, fever, and epigastric pain. Coalescent superficial ulcers with exudate are seen on endoscopy. Culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or in situ hybridization confirms the diagnosis. In biopsies, ulcers and acute inflammatory exudate are present. Viral cytopathic effects are present in the squamous epithelium and include multinucleated cells, ground-glass nuclei, and dense eosinophilic inclusions with a thickened nuclear membrane and clear halo (Cowdry type A inclusions), which are best identified at the edge of the ulcer (Fig. 1.2).

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis affects primarily immunocompromised patients who frequently have multisystem involvement. Symptoms and endoscopic findings are similar to HSV esophagitis. Viral cytopathic changes are best seen in endothelial and stromal cells deep within the ulcer base rather than at the edges and include basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions and the characteristic intranuclear “owl’s eye” CMV inclusion. Viral inclusions may be rare or atypical. Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy because cultures may reflect latent infection and not necessarily active disease.2,4

STOMACH

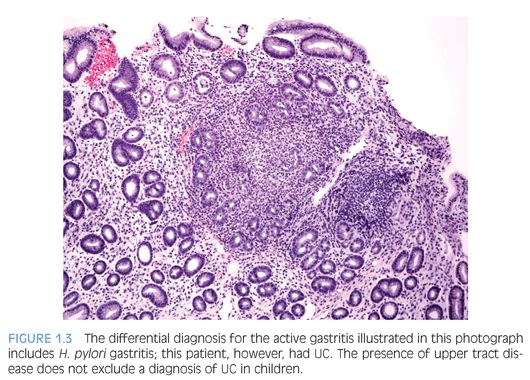

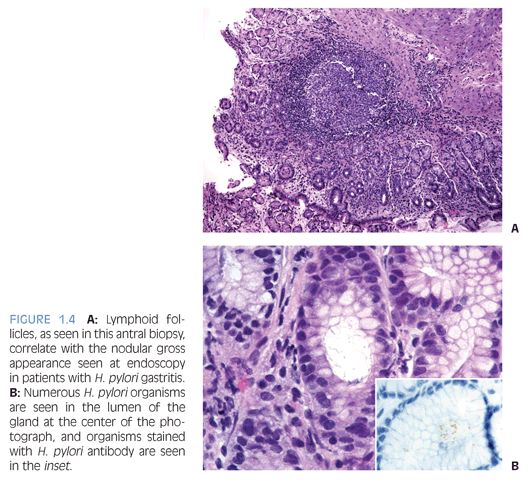

Children who have Helicobacter pylori infection may have high-grade gastritis5 (Fig. 1.3). At least four biopsies, two from the antrum and two from the body, are recommended to increase the diagnostic yield because the infestation may be patchy.6 Special stains and immunohistochemistry may be helpful to identify the organisms in biopsies, and in some cases, there are sufficient numbers of bacteria to be recognized on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain (Fig. 1.4). The urease/Campylobacter-like organism (CLO) test is frequently positive in infected patients. Children may also have infections with Helicobacter heilmannii organisms.7

DUODENUM

Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated enteropathy that is triggered by ingestion of gluten.8 The population prevalence of CD is approximately 1% in the United States and 1.5% in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom.9 CD occurs with higher frequency in certain populations, including patients who have immune disorders including diabetes mellitus, certain chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 21, selective immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency, etc.10

Serologic tests may be helpful to evaluate patients suspected to have CD. Antigliadin (IgA) antibodies are the first autoantibodies to appear following intestinal exposure to gluten11 but are diagnostically useful only in children younger than age 18 months. Tissue transglutaminase (tTGA) and endomysial antibodies (EMA) are the most sensitive antibody tests detecting IgA-class antibodies. Patients who have IgA deficiency should have immunoglobulin G (IgG) class CD-specific antibodies (IgG tTGA or IgG EMA) tests.10 Most patients who have CD have HLADQ2/8 haplotype.

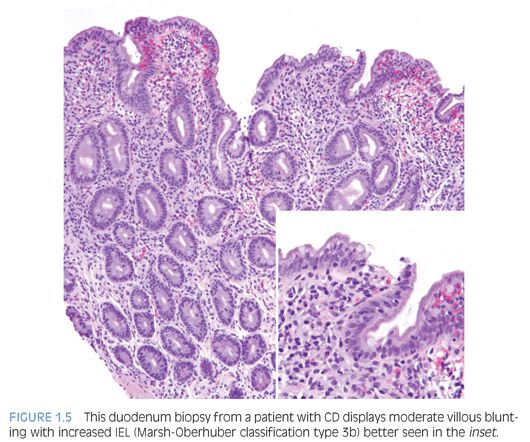

Duodenal biopsies from children and adults who have CD show similar changes, except that neutrophils are more prevalent and abundant in biopsies from children.12 The pathologic changes may be patchy, of variable severity, and in some cases, restricted to the duodenal bulb.10 The pathology report should include evaluation of biopsy orientation, degree of villous atrophy and crypt elongation, the villous–crypt ratio, number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL), and grade based on Marsh-Oberhuber classification10,13 (Fig. 1.5).

IEL are increased in CD duodenal biopsies. In normal duodenum, IEL are more prominent along the lateral edges of villi, decreasing from the base to the tip, the so-called decrescendo pattern. The original threshold value for CD diagnosis was 40 IEL per 100 enterocytes.14 More recently, 25 or more IEL per 100 enterocytes are considered abnormal11 (Table 1.1). Counting IEL per 20 epithelial cells at the tips of five villi or IEL per 50 enterocytes at the tips of two villi may substitute for counts per 100 enterocytes.9 Immunohistochemistry to count IEL has been advocated, but it is not common practice.15

The histologic features of CD are not pathognomonic, and the diagnosis must be confirmed by response to gluten-free diet. The differential diagnosis includes cow’s milk allergy, immunodeficiency, drug reaction, and infections.10,16 eFigure 1.1 illustrates small bowel pathology in cystic fibrosis.

ILEUM

Infections that are associated with granulomatous inflammation, including infections with organisms such as Histoplasma,17 Mycobacterium,18 and Yersinia,19 may occur in the terminal ileum and mimic Crohn disease. Special stains and/or microbiologic culture may be helpful to correctly identify the causative agents.

COLON

Hirschsprung disease (HD), a major genetic cause of functional intestinal obstruction with an incidence of 1 per 5,000 live births, is characterized by absence of intramural ganglion cells in the myenteric (Auerbach) and submucosal (Meissner) plexuses in the rectum and, in many cases, varying lengths of bowel proximal to the rectum.20 HD may be familial; associated with syndromes such as trisomy 21, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, Waardenburg syndrome, etc.; or associated with other anomalies such as congenital heart disease, malrotation, genitourinary anomalies, etc.21 Genes that have been implicated in isolated HD include RET and EDNRB.21,22

HD can be classified, according to the extent of aganglionic bowel, as short segment (SSHD, 80% of HD) and long segment (LSHD, 20% of HD).21 Rarely, HD can involve the entire colon (total colonic aganglionosis) or entire bowel (total intestinal HD). The strong male preponderance in SSHD patients significantly decreases with more extensive aganglionosis.23 Ultrashort segment HD involving the distal rectum24 below the pelvic floor and aganglionic colon proximal to a normal segment of colon25 have also been reported.

HD most commonly presents in newborns as failure to pass meconium, abdominal distension, bilious vomiting, or neonatal enterocolitis but may also be manifest as chronic constipation, abdominal distension, failure to thrive, and recurrent enterocolitis in older children (eFig. 1.2). In affected patients, contrast enema shows dilated proximal colon with narrowing toward the distal aganglionic bowel.26

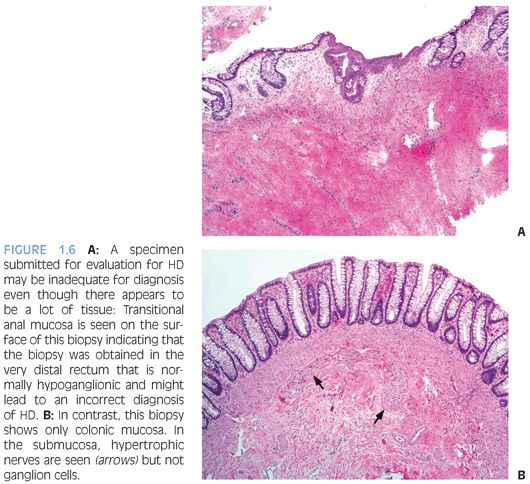

The diagnosis of HD requires demonstration of the absence of ganglion cells from the rectum—a negative characteristic. The diagnosis is most commonly made in rectal biopsies20,27 and must be confirmed by careful examination of the distal end of the resected bowel following surgical therapy. Rectal suction biopsies (RSB) procurement has low morbidity, does not require general anesthesia, and is preferred for neonates and young children.28 However, interpretation of RSB is more challenging than full-thickness surgical biopsies because RSB contain only the superficial portion of the submucosa and not the more abundantly ganglionated deep submucosal and myenteric plexuses. Ideally, RSB measure at least 3 mm in diameter and contain an adequate amount of submucosal tissue that has at least the same thickness as the overlying mucosa.20 In order to avoid false-positive results, RSB should be obtained 2 to 3 cm proximal to the pectinate line because the distal 1 to 2 cm of rectum is normally hypoganglionic.29 Therefore, a specimen containing squamocolumnar junction or transitional anal epithelium (Fig. 1.6) should be considered inadequate for evaluation if ganglion cells are not seen. RSB obtained after an initial inadequate specimen are often of better quality. Nevertheless, transmural rectal biopsies may be required in some cases.

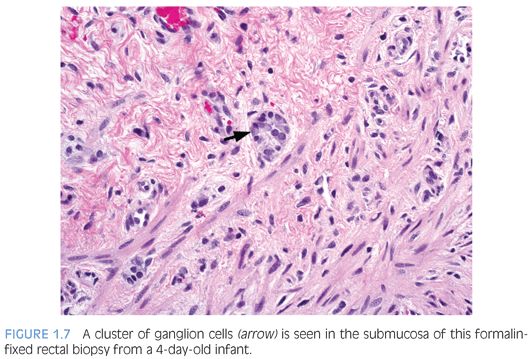

There are various methods to histologically evaluate RSB for ganglion cells (Fig. 1.7). Most laboratories use H&E stains of serial sections, commonly over 50 but up to several hundred, or all sections obtained to exhaust the paraffin block.30 If H&E stains only are used, numerous serial sections must be examined in order to establish the negative characteristic that a normal component of the tissue—ganglion cells—is absent from the tissue. Submucosal hypertrophic nerves (>40µ in diameter) are present in 90% of rectal biopsies from patients with HD and support the diagnosis30,31 (see Fig. 1.6B). However, the original measurements were obtained from infants and young children32 and may be less suitable for older children.33

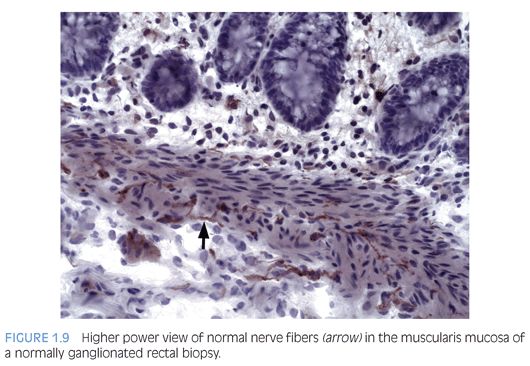

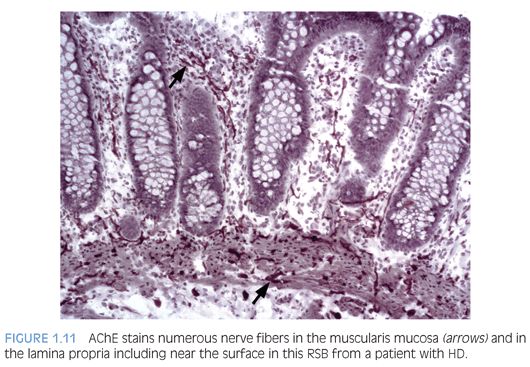

Some laboratories use alternative methods to establish the diagnosis of HD, and some use a combination of serial H&E sections and other stains. The most widely used stain other than H&E is acetylcholinesterase (AChE) histochemistry, which requires frozen tissue. Most laboratories that use AChE on RSB request several pieces to freeze one or more pieces for AChE stains and to fix one or more pieces in formalin; transmural biopsies may be divided with half frozen and half fixed in formalin. In our institution, a series of alternating H&E and AChE stains are prepared on pieces that are frozen and H&E stains are performed on pieces that are fixed in formalin. In a laboratory with experience performing AChE stains and with adequate biopsies, AChE stains combined with H&E stains have been shown to provide a diagnostic yield of 99%.34 The advantage of AChE histochemistry is that it provides a positive finding (Figs. 1.8 to 1.11). In HD, AChE stains identify increased numbers of abnormally thick nerve fibers in the muscularis mucosa and lamina propria that are not seen on H&E stains. Conversely, normal RSB display relatively sparse, delicate AChE-positive fibers limited to the deep muscularis mucosa.

Nonetheless, interpretation of AChE stains is highly dependent on experience interpreting the stain and proper staining technique. Potential pitfalls are the lack of abnormal AChE pattern and absence of submucosal hypertrophic nerves in patients with total colonic aganglionosis,35 equivocal AChE pattern in patients with trisomy 21,36 and low sensitivity of AChE in biopsies from neonates.34 Different diagnostic patterns encountered in RSB are summarized in Table 1.2.

Antibody to the calcium-binding protein calretinin stains delicate nerve fibers in the lamina propria of ganglionated rectal biopsies but not biopsies from HD—a negative finding37–39 (Figs. 1.12 and 1.13). More studies evaluating the clinical use of this stain are required, but some advantages over AChE reaction are easier reproducibility and interpretation and its use in paraffin-embedded tissues. Currently, calretinin immunohistochemistry is an adjunct to and not a substitute for traditional methods of examining RSB.

HD therapy is surgical resection of the aganglionic bowel and creation of a neorectum that includes ganglionic bowel. Definitive surgical procedures (so-called pull-through operations) are performed if RSB or deeper rectal biopsies suggest the diagnosis and should be guided by intraoperative frozen section consultations to identify normally innervated bowel to create the neorectum. In HD, a transition zone occurs between aganglionic bowel and histologically normal bowel and contains varying numbers of ganglion cells and hypertrophic hyperplastic submucosal nerves; the number of ganglion cells increases, and the number of abnormal nerves decreases, with increasing distance from the aganglionic bowel. However, the transition zone length varies, and it commonly does not have a sharp proximal margin but an irregular boundary with normal bowel.40 Therefore, intraoperative seromuscular biopsies or even transmural biopsies can result in the false conclusion that transition zone is not present because the entire circumference of the bowel wall is not examined. The goal of intraoperative frozen section consultation during pull-through procedures for HD is to avoid incorporating transition zone into the neorectum and the subsequent risk for persistent postoperative symptoms sometimes requiring reoperation33,41–43; the best method to achieve this goal is to examine a circumferential transmural section, or doughnut, of bowel that is being considered intraoperatively to become the lead point for the pull-through to document that ganglion cells are present and hypertrophic/hyperplastic nerves are not.

ACUTE SELF-LIMITED COLITIS

Biopsies from patients who have acute self-limited colitis, most often due to infection, may show acute inflammation, even crypt abscesses and mucin depletion, but do not show more specific signs of chronicity such as basal plasmacytosis or basal lymphoid aggregates, crypt distortion, and increased chronic inflammation in the lamina propria.44

IDIOPATHIC INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Bowel preparation is required for adequate examination of colonic and ileal mucosa and may cause mucosal changes that can be distinguished from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) by the lack of signs of chronicity.45,46

There are many similarities between pediatric and adult IBD, but there are several important differences that have resulted in the Paris classification (a modification of the Montreal classification) that more adequately accommodates the differences.47 For example, in children younger than age 10 years at the onset of IBD, Crohn disease is predominantly manifest as colitis.48 Also, histologic evidence of chronicity may be less apparent in biopsies from children who have IBD perhaps because they have not been sick as long as adults.49

Patients who have IBD may have primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC); the outcome for patients who have PSC and IBD is worse than for those who do not have IBD.50

Patients who have glycogen storage disease type 1b may develop bowel inflammation that resembles either Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis.51

Crohn Disease

Upper tract biopsies are helpful to distinguish Crohn disease from UC if granulomas are found.46,52 The association of gastric granulomas with Crohn disease appears to be stronger among children than among adults.53 Dermatologic manifestations, including granulomas, may precede the diagnosis of Crohn disease in children.54 Strictures and penetrating disease are more common in children than adults who have CD.55 Strictures are more common in children older than the age of 10 years.56

The differential diagnosis includes infections associated with granulomatous inflammation17–19 and chronic granulomatous disease (see the following section).

Normal small bowel biopsies do not rule out disease in bowel that is not accessible endoscopically (Fig. 1.14). Computed tomography enteropathy (CTE) is used increasingly to identify small bowel disease in pediatric Crohn disease patients.57

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) tends to be more extensive (pancolitis) in children compared to adults, and children more commonly require hospitalization48,52,58 (Fig. 1.15). Atypical pediatric UC phenotypes include cecal patch in patients with otherwise typical left-sided disease, macroscopic rectal sparing, and upper tract involvement including erosions and ulcers59 (see Fig. 1.3). Rectal biopsies from children who have UC less commonly show diffuse chronic changes compared to adults perhaps because they have not been ill as long as adults.49

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome is uncommon in children and adolescents but may be mistaken clinically for UC; biopsies show features of rectal prolapse.60,61

EOSINOPHILIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASES

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis was originally described in the first half of the 20th century largely based on examination of resected bowel segments. Eosinophil infiltrates concentrated in the mucosa, muscularis propria, or serosa formed the basis for classification, and the protean signs and symptoms were correlated with the layer that was predominantly inflamed.62 In contrast, our knowledge of eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGID) is based on histopathologic examination of exclusively mucosa.63,64 Mural biopsies therefore may be required to identify deeper infiltrates. Nevertheless, a recent review of eosinophilic gastroenteritis concluded that the mucosal form of the disease has increased.62

EGID may be divided into primary forms that include atopy-induced disease and secondary forms that are related to conditions such as hypereosinophilic syndrome, parasitic infections, connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, etc.64,65

Few studies report the number of eosinophils in biopsies that appear to be normal from patients who do not have EGID.66–70 The lack of these data has hampered the ability to develop diagnostic criteria for EGID. The term mucosal eosinophilia may be used to describe biopsies in which eosinophils appear numerous but are distributed normally. However, abnormal numbers of eosinophils in parts of the GI tract where they normally reside in the mucosa (stomach, small and large intestine) may not be required for eosinophil-related bowel dysfunction or a diagnosis of EGID. For example, subcryptal eosinophil aggregates are found in small and large intestine biopsies from patients with diarrhea, some with systemic connective tissue disorders71; this disorder is steroid responsive, and subcryptal eosinophils recur during relapse.

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS. Only in the last decade was eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) recognized as a chronic relapsing antigen-driven disease, not or incompletely responsive to acid suppression therapy.72,73 A threshold value of 15 intraepithelial eosinophils per high-power field (hpf) is recommended for diagnosis. Esophageal biopsies exhibited numerous intraepithelial eosinophils and the associated pathologic changes prior to the recognition of EoE.74–76 Children who had esophageal biopsies that exhibited intraepithelial eosinophils were more likely to have signs of esophageal dysfunction in subsequent years compared to those who did not have intraepithelial eosinophils77 emphasizing the importance of reporting any intraepithelial eosinophils in esophageal biopsies.

The pathologic alterations in esophageal biopsies from patients who have primary or allergic EoE are highly characteristic but not pathognomonic72,73 (Fig. 1.16). Eosinophilic inflammation in the proximal as well as distal esophagus is characteristic of EoE but may occur in other conditions.78 There aren’t any significant differences in the histopathology of EoE in children compared to adults.79

Some patients who have signs of esophageal dysfunction have numerous intraepithelial eosinophils in esophageal epithelium and respond clinically and histologically to PPI therapy, including patients who have, or do not have, abnormal pH monitoring results.73,78,80–82 These patients are currently classified as having PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia; it is not known if they have an unusual form of GERD, an unusual form of EoE, or both.

In addition to eosinophils, other inflammatory cells are increased in EoE and decrease following appropriate therapy.79 The use of antibodies to identify those cells or extracellular eosinophil granule products is not required for diagnosis but may be useful as research tools.

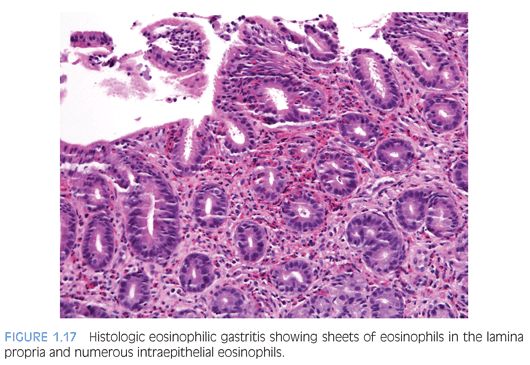

EOSINOPHILIC GASTRITIS. A recent study of gastric biopsies from children and adults that were diagnosed as “histologic” eosinophilic gastritis (EG) suggested an eosinophil count of more than 30 per hpf, based on a count of at least 5 per hpf, is a useful diagnostic criterion.70 In that study of symptomatic patients, eosinophils in epithelium as well as muscularis mucosa and eosinophil sheets in the lamina propria were frequently found (Fig. 1.17). Mural eosinophil infiltrates are found in some patients with gastric outlet obstruction.83–85