Forensic Examination of the Sexual Assault Victim

Robert A. Shapiro

Charles J. Schubert

Introduction

Physicians are often called on to evaluate children who may have been victims of sexual abuse. It is estimated that 20% of American women and 5% to 10% of American men will experience some form of sexual abuse as children (1). Evaluation for sexual abuse includes a history from the alleged victim and/or guardian and a physical examination. When indicated, laboratory tests for sexually transmitted diseases and forensic specimens for the police are obtained. In this chapter, the term “forensic specimens” refers to samples collected for a police investigation, not for medical treatment. The procedure must be performed with precision and documentation must be complete because the evaluation may later be scrutinized in a court of law. Procedures presented in this chapter will satisfy legal requirements when performed properly.

Many communities have a multidisciplinary facility designated as a child advocacy center (CAC) that is equipped to evaluate allegations of sexual abuse. The medical evaluation of nonacute alleged sexual abuse, and in some communities acute assault, can often be provided by the CAC, and such an evaluation would be preferred to an evaluation in the emergency department. Protocols with the local CAC should be written so that guidelines for triage of alleged sexual abuse/assault patients are created.

Sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) are available to assist in the evaluation of forensic evidence in many communities. Because the evaluation of the child abuse victim is different from that of the adult victim, SANE nurses who evaluate children for suspected child sexual abuse/assault should complete appropriate training and demonstrate competency in child sexual abuse evaluations. Pediatric SANEs can collect laboratory specimens, forensic specimens, and diagnostic-quality photo documentation. If trained in forensic interview methods, the Pediatric SANE can also obtain a history from the child. Pediatric SANEs should document their involvement in the medical record using standard nursing methods and vocabulary. The interpretation and diagnosis should be made by an experienced physician or clinical nurse practitioner.

Anatomy and Physiology

Before conducting an evaluation, the anatomy of the genitalia and the examination techniques presented in Chapters 91 and 93 should be reviewed. The appearance of the normal genitalia changes dramatically from infancy to childhood to adolescence. Many “normal” variants of the prepubertal and adolescent hymen are encountered, as well as great variation in the normal color and skin appearance of the anus. Errors in clinical judgment may occur if the physician is unfamiliar with the normal range of anatomic findings and the changes that occur with age.

The physical examination of most victims of sexual abuse will be normal (see Fig. 91.2) (2,3). Abuse by fondling and oral contact, for example, usually causes no identifying physical signs. Penetration of a young child’s vagina may result in injury and recognizable findings on examination. Penetration of the vulva without introitus penetration in the young child, or introitus penetration in the pubertal female, most often causes no injury. Rectal and penile injuries are unusual. The amount of force used, the frequency of abuse, the use of lubricants, the size of the object penetrating the child, and the child’s age are factors that will determine the likelihood of injury and an abnormal examination. Furthermore, when injuries heal, findings of trauma are often absent.

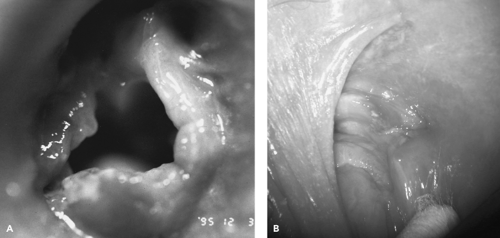

The most specific indicators of vaginal penetration are injuries to the hymeneal ring. Acute trauma is indicated by bleeding, fresh tears, abrasions, or bruising to the hymen or to one of the structures immediately adjacent to the hymen (Fig. 94.1). Healed trauma from vaginal penetration is difficult to recognize and should be diagnosed by a physician or clinical nurse practitioner skilled in this field. Small notches, bumps, minor irregularities, absence of hymen between 10 and 2 o’clock, redundant hymeneal tissue, labial adhesions, and erythema are examples of nonspecific findings (4). Speculum examinations in the prepubertal patient are indicated only when internal injury is suspected. An internal vaginal exam in the prepubertal patient will require anesthesia.

Penetration of the rectum in sexual abuse may cause lacerations or perianal bruising. Normal exams are common. Rectal tone should be assessed by observation of the anal diameter as the buttocks are spread apart. Stool in the rectal vault may cause decreased rectal tone and should be ruled out by re-examining the child after voluntary defecation. A digital rectal examination and anoscopy are necessary only when serious internal trauma is suspected.

Straddle injuries to the genitalia are a common cause of genital trauma and result in asymmetric bruising of and lacerations to (a) the skin overlying the pubic symphysis or (b) the labia majora. Because these injuries generally only involve the surface structures, sexual abuse should be suspected if the trauma involves the hymen.

Indications

Evaluation for sexual abuse or assault is needed whenever illegal sexual activity has been alleged, disclosed, or discovered. The definition of illegal sexual activity varies from state to state. When in doubt about whether a crime has been committed, police or social services from that jurisdiction should be consulted. In most states, any sexual activity with a child under 13 years of age is illegal and requires an evaluation. Teenagers between the ages of 13 and 15 who have sexual activity with a partner 4 or more years older may be engaging in illegal activity. Incest and any sexual activity that is forced on a minor against his or her will must be evaluated and reported.

Children who are victims of sexual abuse frequently report fondling of their genitalia or rectum, oral sex, attempted intercourse, sodomy, or demands to masturbate the perpetrator. Most often the perpetrator is a male who has access to the child, such as a member of the child’s family, a close family friend, or one of the child’s caretakers. Sexual abuse occurs in children of all ages. Of the victims, 85% are female. The child may disclose the abuse, or it may be discovered by others. The last incident of abuse before evaluation may have been years ago or within hours of presentation.

Experts differ on the indications for sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing in cases of sexual abuse. A suggested approach is presented in Figure 94.2. Testing all adolescent victims is warranted given the high incidence of STIs in this population. If the victim is an asymptomatic prepubertal child, testing is recommended if the prevalence of STIs is high in the community in which the child lives or if the history suggests an increased risk of infection. Symptomatic prepubertal children should have infections documented by culture or another gold standard test. Children diagnosed with one STI should be tested for others.

In most locations, forensic specimens must be collected if the last abuse or assault occurred within 72 to 96 hours of

the evaluation and if the history suggests that semen, saliva, blood, or hair of the alleged perpetrator may be found on the victim’s body or clothing (5,6).

the evaluation and if the history suggests that semen, saliva, blood, or hair of the alleged perpetrator may be found on the victim’s body or clothing (5,6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree