Disorders of the Epidermis

Kristen E. Holland

Primary skin diseases that principally affect the epidermis may be categorized as either a dermatitis or a papulosquamous disorder. Dermatitis commonly denotes inflammation of the epidermis. Eczema generically denotes edema within the epidermis. Many primary dermatitides are eczematous in nature, although the term eczema is often misused interchangeably for atopic dermatitis.  Vesicles are often subclinical in subacute or chronic eczemas where edema is mild but present as grossly evident vesicles and bullae in acute eczemas. Papulosquamous eruptions are characterized by the presence of erythematous papules or plaques with overlying scale. While eczematous processes clinically manifest with weeping or crusting, papulosquamous disorders are associated with little to no edema and thus clinically tend to be dry.

Vesicles are often subclinical in subacute or chronic eczemas where edema is mild but present as grossly evident vesicles and bullae in acute eczemas. Papulosquamous eruptions are characterized by the presence of erythematous papules or plaques with overlying scale. While eczematous processes clinically manifest with weeping or crusting, papulosquamous disorders are associated with little to no edema and thus clinically tend to be dry.

ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Atopic dermatitis is the most common chronic inflammatory childhood skin disease, characterized by intense itching, dry skin, inflammation, and exudation. The typical clinical finding is an ill-defined patch or plaque of scaling and erythema. Pruritus is a constant feature. Chronic scratching results in dramatic accentuation of the skin markings (lichenification), sometimes with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, whereas the chronic eczematous process itself may result in hypopigmentation.

The pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis is not completely understood. It is likely multifactorial involving interplay between immune, genetic, metabolic, infectious, and environmental factors.2 Abnormalities of the epidermal barrier paired with immune dysregulation culminate in expression of this disease. A genetic basis for abnormal barrier function in some patients with atopic dermatitis has recently been linked to the FLG gene, the gene in which null mutations result in ichthyosis vulgaris, a scaly skin disorder in which 20% to 25% of people are also atopic.3 The FLG gene encodes filaggrin, a protein essential for epidermal barrier formation and hydration. The role of filaggrin (or of its absence) in the development of atopic dermatitis is not completely understood.

In infancy, involvement of the face, particularly the cheeks (Fig. 358-1), and of extensor surfaces of the extremities is typical, but involvement of the scalp and trunk is also common. In older children, atopic dermatitis favors the flexures such as the antecubital and popliteal fossae. Ankles, wrists, and dorsa of hands and feet are also commonly involved (eFig. 358.1  ). Occasionally, disease is widespread and severe. A papular variant may be seen, particularly in African American patients (eFig. 358.2

). Occasionally, disease is widespread and severe. A papular variant may be seen, particularly in African American patients (eFig. 358.2  ). Several subtle physical findings may support the diagnosis, including accentuation of skin markings on palms and soles, double or triple creases under the lower eyelid (Dennie-Morgan folds), conspicuous sparing of the central face (“headlight sign”), and small fissures at the base of the ear lobe. Generalized xerosis (dry skin) is almost invariably present. Other primary skin diseases that can mimic atopic dermatitis include seborrheic dermatitis (particularly in infants), scabies, allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis, ichthyoses, cutaneous lymphoma, and immunodeficiency. Atopic dermatitis is a clinical diagnosis because there are no specific diagnostic tests.

). Several subtle physical findings may support the diagnosis, including accentuation of skin markings on palms and soles, double or triple creases under the lower eyelid (Dennie-Morgan folds), conspicuous sparing of the central face (“headlight sign”), and small fissures at the base of the ear lobe. Generalized xerosis (dry skin) is almost invariably present. Other primary skin diseases that can mimic atopic dermatitis include seborrheic dermatitis (particularly in infants), scabies, allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis, ichthyoses, cutaneous lymphoma, and immunodeficiency. Atopic dermatitis is a clinical diagnosis because there are no specific diagnostic tests.

The treatment of infants and children with atopic dermatitis must be individualized and based on disease severity. It is useful to divide therapeutic strategies into those aimed at treating the rash and those aimed at preventing future disease. Parents tend to focus on identification of “the cause.” It is unusual, however, that one or a few environmental factors can be identified that, when eliminated, will lead to a “cure.” Rather, this is a condition of inherited skin “sensitivity”; that is, a variety of precipitating factors, such as dry skin (xerosis), heat, infection, specific allergens, topical irritants, and/or psychological state may be responsible, to varying degrees, for a given flare of the disease. Once established, the dermatitis tends to be self-perpetuating such that elimination of the original inciting factors may not lead to resolution of the rash. Therefore, it is important that initial efforts be directed toward treatment of the dermatitis and its complications.

FIGURE 358-1. Typical facial erythema and crusting in an infant with atopic dermatitis.

The most significant aspect of preventive therapy is decreasing skin dryness. This aim may be achieved by the liberal and frequent (2–3 times daily) use of emollients (ointments are preferred to creams and particularly to lotions) and by avoidance of strongly alkaline soaps. Daily baths in warm (not hot) water can hydrate skin and débride crust and will not adversely affect disease, provided moisturizing cleansers are used and emollients are applied immediately after. Emollients are first-line agents in the management of atopic dermatitis and may be steroid sparing. Attention to other factors that induce pruritus, such as woolen or synthetic fabrics, heat, sweating, and stress, is also important in the management of atopic dermatitis. Most children respond to standard dermatologic therapy and do not require investigation of dietary triggers or food avoidance.

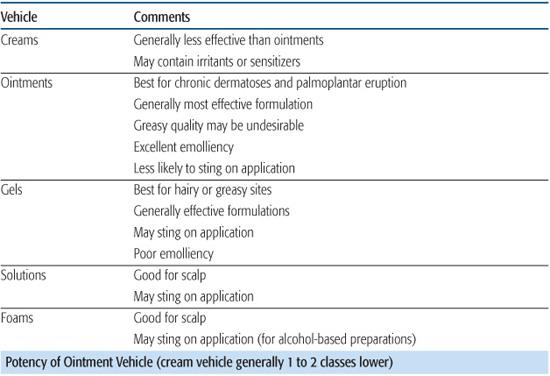

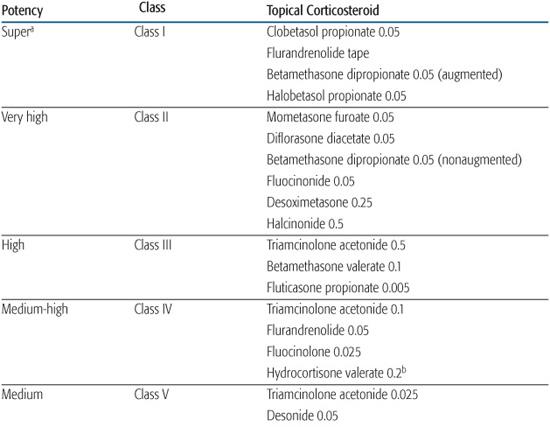

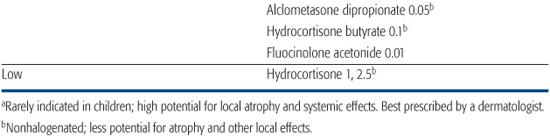

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line therapy for management of disease exacerbations. For most patients, atopic dermatitis can be adequately and safely controlled with low- and medium-potency topical corticosteroids (Table 358-1). Twice daily application is recommended; there is no evidence that more frequent application enhances efficacy.2 In general, the mildest corticosteroid that will be effective should be chosen. In more severe flares or on unresponsive lesions, a medium- to high-potency steroid may be indicated. Once control is achieved, patients should be switched to a milder corticosteroid; thereafter, use of higher-potency steroids should be limited to focal, resistant lesions.

Because of their better emolliency and greater potency, ointments are generally preferred over creams. However, some patients with atopic dermatitis may not tolerate ointment vehicles because of increased pruritus. The prolonged use of potent corticosteroids can result in local skin atrophy, manifested by transparent skin with prominent blood vessels, telangiectasia, and cigarette paper–like wrinkling, which is indicative of epidermal thinning. Atrophy, if unrecognized, may progress to permanent striae formation. Topical steroids must be used cautiously on the face and groin, where side effects are more common. Systemic effects depend on the inherent potency of the corticosteroid, its percutaneous transport, the relative surface area treated, and the surface area–body volume ratio. With appropriate use, topical corticosteroids are not associated with significant adverse effects (eg, suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis or growth).2

Topical calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus (0.03% and 0.1% ointment) and pimecrolimus (1% cream), are considered as second-line therapy for the management of atopic dermatitis. Topical tacrolimus 0.03% and pimecrolimus are approved for use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in children over 2 years old. Concern about potential long-term adverse effects exists, and these agents carry a warning from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stating that rare cases of malignancy (eg, skin cancer and lymphoma) have developed in patients treated with these agents, although a causal relationship has not been established.  Future studies examining systemic absorption of these agents in infants and young children and evaluating their long-term safety are needed to better define their role in the management of atopic dermatitis.

Future studies examining systemic absorption of these agents in infants and young children and evaluating their long-term safety are needed to better define their role in the management of atopic dermatitis.

Oral antihistamines are useful adjuncts to therapy for control of pruritus. Nonsedating antihistamines are not particularly effective. Oral antibiotics may be indicated in children who show evidence of superinfection, such as serous crusting of lesions or follicular pustules, or in children who are not responding to therapy. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy is not advisable because of the potential for emergence of antibiotic resistance. Dilute bleach baths (1/4 to 1/2 cup of a 6% sodium hypochlorite solution in a bathtub of water) for 10 to 15 minutes, 2 to 3 times a week, may decrease bacterial colonization and need for systemic antibiotics.

Although systemic corticosteroids almost invariably result in rapid improvement, attempts to taper or discontinue the drug are very commonly associated with a severe rebound flare. Because of this problem, and in view of the numerous side effects associated with their long-term use, systemic corticosteroids should be avoided in the management of atopic dermatitis. Most patients experiencing a severe generalized flare will respond within 3 to 5 days to a course of intensive topical therapy using wet wraps. This treatment consists of application of the topical steroid to affected areas (typically triamcinolone 0.1% ointment) followed by wrapping the areas with soft cotton cloths soaked in warm tap water and then an outer occlusive plastic wrap, leaving the wraps in place for 20 to 30 minutes and repeating this 3 times a day. In cases of a severe flare, antihistamines should be given in sedative doses, and any secondary bacterial, fungal, or viral infections treated. Patients in whom this regimen fails at home will invariably respond in the hospital.

For older patients with moderate to severe disease recalcitrant to topical therapies, ultraviolet light therapy may be beneficial.  Long-term concerns regarding the use of phototherapy include photodamage and the potential increased risk of skin cancer.

Long-term concerns regarding the use of phototherapy include photodamage and the potential increased risk of skin cancer.

Systemic immunomodulators, including cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, can be effective for severe atopic dermatitis unresponsive to other therapies. Limited studies of their efficacy and safety in children exist. Use of these medications requires close monitoring for potential side effects and prevention of long-term sequelae.

Atopic individuals are at risk for widespread cutaneous infection with molluscum contagiosum and herpes simplex (eczema herpeticum). The latter presents as multiple vesicles or punched-out erosions that may be grouped or dispersed and are found on both normal and eczematized skin (eFig. 358.3  ). Whereas Staphylococcus aureus is not normally resident on skin, both uninvolved and involved areas in atopic individuals can be colonized with S aureus. Impetiginized lesions are a frequent complication of atopic dermatitis and manifest as serous crusting.

). Whereas Staphylococcus aureus is not normally resident on skin, both uninvolved and involved areas in atopic individuals can be colonized with S aureus. Impetiginized lesions are a frequent complication of atopic dermatitis and manifest as serous crusting.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by frequent remissions and exacerbations. Parents and children must understand that the treatments outlined here suppress the disease process but do not result in cure. Fortunately, the majority of children improve with age, and most are free of disease by adolescence. A national support group, the National Eczema Association (http://www.nationaleczema.org), provides patient information and support.

Table 358-1. Topical Corticosteroid Therapy

Several other skin disorders are more common in children with atopic dermatitis or with a familial atopic diathesis. Pityriasis alba is common in school-aged children and is characterized by ill-defined areas of hypopigmentation, often with a fine scale (Fig. 358-2). It occurs most commonly on the cheeks but may be seen in other locations. The pathologic process is that of a mild eczema, often caused by overdrying of the skin, which may be subclinical, and is followed by postinflammatory hypopigmentation, most evident in dark-skinned children. While bland emollients are often helpful and important for maintenance, a mild topical corticosteroid ointment (eg, 1% hydrocortisone) may be used to treat the dermatitis; with time repigmentation will follow.

CONTACT DERMATITIS

Contact dermatitis occurs when the skin adversely reacts with outside agents either from direct irritation (irritant contact dermatitis) or as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction (allergic contact dermatitis). Primary irritant contact dermatitis is caused by the direct effects of chemicals or physical substances on the skin. Irritant diaper dermatitis is the most common and classic example of a primary irritant contact dermatitis occurring from contact with urine and feces (see “Diaper Dermatitis” in this chapter). Liplicker’s dermatitis is another common example of an irritant contact dermatitis that occurs as a result of repeated contact of saliva with perioral skin (eFig. 358.4  ). Other common primary irritants are detergents, acids, alkalis, and harsh soaps. It is uncommon to see frank vesiculation in irritant contact dermatitis compared to allergic contact dermatitis.

). Other common primary irritants are detergents, acids, alkalis, and harsh soaps. It is uncommon to see frank vesiculation in irritant contact dermatitis compared to allergic contact dermatitis.

FIGURE 358-2. Pityriasis alba. Note ill-defined hypopigmented macules on cheek of young child. Preceding eczematous changes are also evident as erythema with slight scale.

Historically, allergic contact dermatitis has been considered to be rare in children, but recent studies suggest it occurs more commonly than previously thought.6,7 A study of asymptomatic general pediatric patients under 5 years of age found a sensitization rate of 24.5% with sensitization demonstrated as young as 6 months.8 As a result of increased exposures and sensitization, the prevalence of allergic contact dermatitis generally increases with advancing age. It is a form of delayed T-cell hypersensitivity reaction (type IV).7

Acute allergic contact dermatitis is characterized by intense pruritus, erythema, and vesiculation in contrast to chronic reactions, which are scaly rather than vesicular. An intensely pruritic eruption begins 7 to 14 days after exposure in primary sensitization reactions and after 1 to 4 days in subsequent exposures.  Transfer of antigen to areas of sensitive skin (eg, face and eyelids, penis and scrotum) may result in marked dermal edema and swelling. Widespread papular eruptions or “id” reactions characterized by pruritic papules in nonexposed areas can be triggered by a local atopic dermatitis. At times, the diagnosis of contact dermatitis may be evident by the presence of geometric shapes or linear configurations, which suggest an external cause, but it can often be difficult to distinguish from other eczematous conditions, such as atopic or irritant dermatitis.

Transfer of antigen to areas of sensitive skin (eg, face and eyelids, penis and scrotum) may result in marked dermal edema and swelling. Widespread papular eruptions or “id” reactions characterized by pruritic papules in nonexposed areas can be triggered by a local atopic dermatitis. At times, the diagnosis of contact dermatitis may be evident by the presence of geometric shapes or linear configurations, which suggest an external cause, but it can often be difficult to distinguish from other eczematous conditions, such as atopic or irritant dermatitis.

The most common cause of acute allergic contact dermatitis among children in the United States is exposure to poison ivy, oak, or sumac, all members of the genus Toxicodendron (formerly, Rhus) (eFig. 358.6  ). Nickel allergy is the most common cause of subacute or chronic allergic contact dermatitis and is usually localized to sites where earrings, bracelets, necklaces, or the metal clasp or zipper of a garment comes into contact with the skin (Fig. 358-3). Id reactions are particularly common with nickel-induced atopic dermatitis, developing in as many as 50% of affected children (eFig. 358.7

). Nickel allergy is the most common cause of subacute or chronic allergic contact dermatitis and is usually localized to sites where earrings, bracelets, necklaces, or the metal clasp or zipper of a garment comes into contact with the skin (Fig. 358-3). Id reactions are particularly common with nickel-induced atopic dermatitis, developing in as many as 50% of affected children (eFig. 358.7  ).9 Earlobe involvement commonly presents with redness and oozing at the pierced site and can be mistaken for bacterial infection. Jewelry made of surgical stainless steel or 24-karat gold is usually tolerated. Other common causes of allergic contact dermatitis include preservatives and vehicle chemicals in topical preparations and cosmetics, fragrances, and adhesives in tapes or bandages. Shoe allergy presents as a scaly, pruritic eruption on the dorsum of feet and toes (eFig. 358.7

).9 Earlobe involvement commonly presents with redness and oozing at the pierced site and can be mistaken for bacterial infection. Jewelry made of surgical stainless steel or 24-karat gold is usually tolerated. Other common causes of allergic contact dermatitis include preservatives and vehicle chemicals in topical preparations and cosmetics, fragrances, and adhesives in tapes or bandages. Shoe allergy presents as a scaly, pruritic eruption on the dorsum of feet and toes (eFig. 358.7  ). The antigen may be rubber or rubber accelerators, adhesives, tanning agents, dyes, or leather. Neomycin and the “-caine” type of topical anesthetics are frequent sensitizers.

). The antigen may be rubber or rubber accelerators, adhesives, tanning agents, dyes, or leather. Neomycin and the “-caine” type of topical anesthetics are frequent sensitizers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree