Delivery in the Emergency Department

Isaac Delke

In the United States, 99% of all births have been in hospitals over the past several decades (1). In many areas, the emergency department (ED) is where the obstetric patient enters the hospital. These patients are subsequently sent to the labor and delivery suite if the hospital has an obstetric service. Sometimes, however, emergency medical system (EMS) personnel and/or ED staff are faced with a gravida ready to deliver, and they must be prepared to handle such a situation. The apprehension experienced by emergency birth attendants is not simply due to the lack of expertise with normal deliveries but also is due to the awareness of the potential for serious maternal and perinatal complications.

This chapter presents basic steps in the management of imminent delivery. It focuses on (i) EMS preparedness, (ii) normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, and (iii) complications of vaginal delivery (shoulder dystocia, breech presentation, cord prolapse, and postpartum hemorrhage and/or perineal lacerations). Preparedness and knowledge of the management of obstetric emergencies that commonly confront the ED staff maximize the potential for effective intervention and optimal outcome.

EMS PREPAREDNESS

EMS personnel must be trained to recognize and manage precipitate delivery appropriately. This requires knowledge by EMS personnel of available obstetric and neonatal units in the system’s catchment area for appropriate transport. The transport team should be trained to assist in the precipitate delivery of an infant and skilled in the use of basic obstetrical kits. Prehospital protocols should be reviewed often so that EMS personnel remain prepared for the rare and potentially catastrophic pregnancy-related events. Whether patients deliver in the prehospital setting or on immediate arrival to the ED, every ED should be ready for emergency delivery by preparing a basic delivery kit, along with resources for the initial care and potential resuscitation of the newborn (Table 12.1). Because of the relatively infrequent delivery in the prehospital setting or ED, extra care should be taken to educate EMS and ED personnel through educational programs, annual in-services, and equipment orientation sessions.

SPONTANEOUS VAGINAL DELIVERY

The initial step in the management of a woman in active labor is to obtain vital signs and initiate supportive therapy, including obtaining venous access and monitoring the mother and fetus. Pelvic examination should reveal fetal presentation, including visible or palpable head or, in the case of breech presentation, the fetal buttock or extremity. Sometimes, confirmation of fetal cardiac activity and presentation may be accomplished using portal ultrasound. The stage of labor and the parity of the patient should be taken into account when considering transport of a patient in labor to another facility or to the labor and delivery suite.

TABLE 12.1 Basic Emergency Delivery Kit | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Delivery of the Head

If delivery of the head is already well on its way, the attending physician should prepare for the delivery after a stat call to obstetric and pediatrician staff. Ideally, the patient should be on the delivery table in the lithotomy position. If the patient is on a bed or stretcher, her legs should be supported. As time allows, the perineum may then be prepared by washing with mild soap and water and swabbing with povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine topical solution. Drapes should be placed over the patient, and the birth attendant should use gowns, masks, and gloves. The mother should be informed, assured, and instructed to enhance maternal cooperation to accomplish a controlled delivery. If the fetus is dead, there is no risk of further fetal trauma, and focus is totally on the mother.

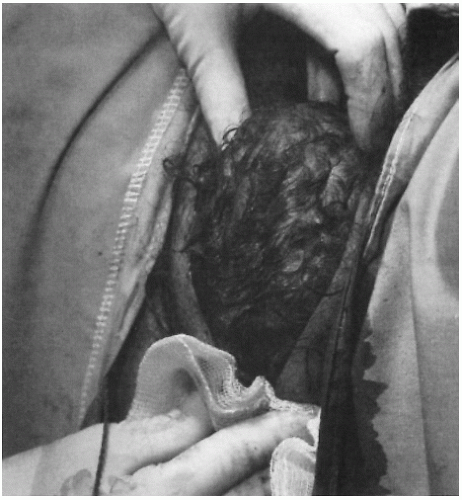

The Ritgen Maneuver

As the head becomes increasingly visible, the vaginal outlet and vulva are stretched until they ultimately encircle the largest diameter of the baby’s head (crowning). As the infant’s head emerges from the introitus, the perineum should be supported by placing a sterile towel along the inferior portion of the perineum. Forward pressure should be extended on the chin of the fetus through the perineum just in front of the coccyx, while the other hand exerts mild counterpressure superiorly against the occiput to prevent rapid expulsion of the fetal head, which may lead to perineal or periurethral tears (Fig. 12.1). It also favors extension of the head, so that delivery occurs with its smallest diameters passing through the introitus and over the perineum. The head is delivered slowly, with the base of the occiput rotating around the lower margin of the symphysis pubis as a fulcrum, while the bregma (anterior fontanel), brow, and face pass successively over the perineum (2,3). The mother is then asked to breathe through contractions rather than bearing down and attempting to push the baby out rapidly.

The use of routine episiotomy for a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery has been discouraged in recent years, because it has been demonstrated to

increase the incidence of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations occurring at the time of delivery. If an episiotomy is necessary, it may be performed as follows: 5 to 10 mL of 1% lidocaine solution is injected with a 25-gauge needle into the posterior fourchette and perineum. While protecting the fetal head, a 2 to 3 cm midline cut is made with scissors to extend the vaginal opening. The incision must be supported with manual pressure from below, taking care not to allow the incision to extend into the rectum.

increase the incidence of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations occurring at the time of delivery. If an episiotomy is necessary, it may be performed as follows: 5 to 10 mL of 1% lidocaine solution is injected with a 25-gauge needle into the posterior fourchette and perineum. While protecting the fetal head, a 2 to 3 cm midline cut is made with scissors to extend the vaginal opening. The incision must be supported with manual pressure from below, taking care not to allow the incision to extend into the rectum.

Delivery of the Shoulders

After delivery of the head, the occiput promptly turns toward one of the maternal thighs, so that the head assumes a transverse position. The successive movements of restitution and external rotation indicate that the bisacromial diameter (transverse diameter of the thorax) has rotated into the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis. The anterior shoulder should then be delivered by gentle downward traction in concert with maternal expulsive efforts. Traction should be exerted only in the direction of the long axis of the infant, because, if applied obliquely, it causes bending of the neck and excessive stretching of the brachial plexus. The posterior shoulder is then delivered by upward traction. Some practitioners, including the author, prefer to deliver the anterior shoulder prior to its external rotation (head-and-shoulder delivery) to avoid potential shoulder dystocia. The rest of the body almost always follows the shoulders without difficulty. A point of practical concern is the need to maintain control of the newly born infant such that inadvertent dropping does not occur.

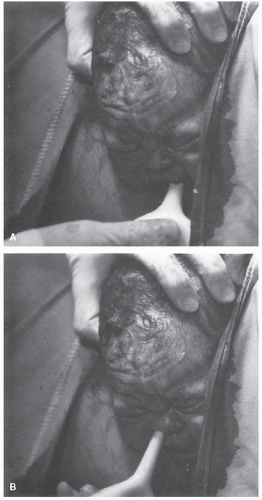

Clearing the Nasopharynx

To minimize the likelihood of aspiration of amniotic fluid debris, meconium, and blood that might occur once the thorax is delivered and the infant can inspire, the face is quickly wiped and the nares and mouth are aspirated (Fig. 12.2). A soft rubber ear syringe or its equivalent, inserted with care, is suitable for this purpose.

Nuchal Cord

After delivery of the head and anterior shoulder, check for a nuchal cord by passing a finger around the fetal neck. A nuchal cord occurs in about 25% of cases and ordinarily does no harm. If a cord is felt, it should be drawn down between the fingers and, if loose enough, slipped over the infant’s head. If it is applied too tightly to the neck to be slipped over the head, it should be cut between two clamps only after delivery of the anterior shoulder and the infant should be delivered promptly.

Clamping the Cord

The timing of cord clamping should be dictated by convenience, and cord clamping is usually performed immediately after delivery of infant. The cord is clamped after thoroughly clearing the infant’s airway, which usually takes about 30 seconds. The infant is not elevated above the introitus at vaginal delivery. The umbilical cord is cut between two clamps placed 4 or 5 cm from the fetal abdomen. Later, an umbilical cord clamp is applied 2 or 3 cm from the fetal abdomen. A segment of the umbilical cord is saved for blood gas analysis.

Delivery of the Placenta

The placenta should be allowed to separate spontaneously. Immediately after delivery of the infant, the height of the uterine fundus and its consistency are ascertained. As long as the uterus remains firm and there is no unusual bleeding, the usual practice is to watch carefully for any of the following signs of placental separation.

1. The uterus becomes globular and firm. This sign is the earliest to appear.

2. There is often a sudden gush of blood.

3. The uterus rises in the abdomen because the placenta, having separated, passes into the lower uterine segment and vagina, where its bulk pushes the uterus upward.

4. The umbilical cord protrudes farther out of the vagina, indicating that the placenta has descended.

These signs usually appear within 5 minutes. The mother may be asked to bear down, and the intra-abdominal pressure so produced may be adequate to expel the placenta. If these efforts fail, the attendant, again having made certain that the uterus is contracted firmly, lifts the fundus cephalad with the abdominal hand, keeping the umbilical cord slightly taut (Brandt-Andrews method). Aggressive traction on the cord risks uterine inversion, tearing of the cord, or disruption of the placenta, which can result in severe vaginal bleeding (2,3). As the placenta passes through the introitus, pressure on the uterus is stopped. The placenta is then gently lifted away from the introitus. Care is taken to prevent the membranes from being torn off and left behind. If the membranes start to tear, they are grasped with a ring forceps and removed by gentle traction. After removal of the placenta, the uterus should be massaged gently to promote contraction. The placenta, membranes, and umbilical cord should be examined for

abnormalities of cord insertion, confirmation of a three-vessel cord, and completeness of removal of placenta and membranes.

abnormalities of cord insertion, confirmation of a three-vessel cord, and completeness of removal of placenta and membranes.

Oxytocin Agents

After delivery of the placenta, the primary mechanism by which hemostasis is achieved at the placental site is by a well-contracted myometrium. Oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon, etc.), ergonovine maleate (Ergotrate), methylergonovine maleate (Methergine), and misoprostol (Cytotec) are used in various ways in the conduct of the third stage of labor, principally to stimulate myometrial contractions and thereby reduce the blood loss (Table 12.2).

Oxytocin, ergonovine, methylergonovine, and misoprostol are all used widely in the conduct of the normal third stage of labor, but the timing of their administration differs at various institutions. Oxytocin, and especially ergonovine, given before delivery of the placenta will decrease blood loss somewhat. However, the use of oxytocin, and especially ergonovine or methylergonovine, before delivery of the placenta may entrap an undiagnosed, and therefore undelivered, second twin. This may prove injurious, if not fatal, to the entrapped fetus. In most cases following uncomplicated vaginal delivery, the third stage of labor can be conducted with reasonably little blood loss.

TABLE 12.2 Medications for Emergency Delivery and Indications for Use | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|