Conjoined Twins

John H.T. Waldhausen

Department of Surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine, Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle, Washington 98115.

Conjoined twins represent a fascinating challenge for the entire medical team involved in the care of these children. The separation of these children may in some cases be quite simple, whereas in others it is extremely complex. Meticulous planning and a team approach offer the best chance for a successful outcome to those infants who are separable.

HISTORY

Conjoined twins have been known since antiquity (1,2,3,4). Presently, more than 500 sets of twins have been described with more than 200 attempts at surgical separation. Since 1950, an increasing number of twins have undergone successful separation, yet the operations remain a distinct challenge with many ethical and surgical problems to consider (2).

INCIDENCE

The incidence of conjoined twinning varies in different parts of the world, from 1:100,000 to 250,000 in the United States to 1:50,000 in parts of Africa, with some isolated reports indicating a frequency as much as 1:14,000 (5). In the United States, 40% of these infants are stillborn and another 35% die within the first 24 hours of life (6). Prenatal diagnosis and planned cesarean section have increased survival over what was experienced with vaginal delivery (7). Seventy percent of conjoined twins who survive long enough to undergo separation are female, whereas most stillborn conjoined twins are male.

EMBRYOLOGY

Conjoined twins have been reported in both the plant and the animal kingdoms (8). The embryology of conjoined twins is controversial and is for the most part theoretical because, for ethical reasons, there is no model to study this in humans. Conjoined twinning occurs during the third to fourth week of gestation and may be considered either as a result of incomplete fission or of partial fusion. Much of the evidence for incomplete fission is circumstantial, although this has usually been viewed as the most likely cause (8). Conjoined twins are almost always monoamniotic and of the same sex, although diamniotic omphalopagus twins have been reported (9). Conjoined twins have been reported as one of a set of triplets or quadruplets and, in fact, there are rare reports of conjoined tripling and quadrupling (10). When a pair of conjoined twins is part of a set of triplets or quadruplets, the conjoined twins are always isosexual, whereas the other infant may be of the opposite sex. One would surmise that if conjoined twins occurred as a process of fusion, that opposite sex twins would be as likely to fuse as would same-sex infants. This has never, however, been noted to occur, although several cases of pseudohermaphroditism have been documented (10).

Conjoined twins are always joined in a homologous fashion; in other words, they are always fused back to back, front to front, cranial to cranial, or caudal to caudal. They are never fused head to tail and so on. Twins can be divided into two groups: those with ventral union of two early embryonic discs over a single yolk sac (cephalopagus, thoracopagus, omphalopagus, ischiopagus, and parapagus), and those fused dorsally by two originally separate neural tubes (craniopagus, rachipagus, pygopagus). Twins often have multiple anomalies in multiple organ systems. These anomalies are typically found in male infants and the right-sided twin (10).

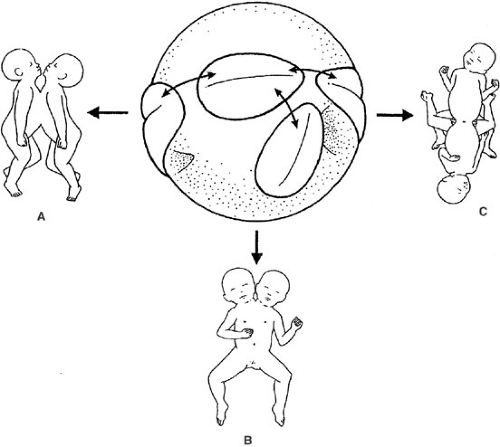

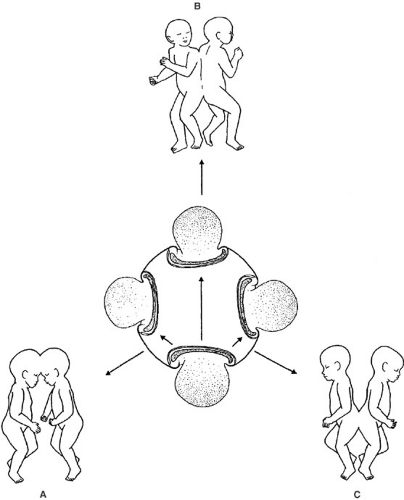

Development by fusion is supported by theoretical work performed by Dr. Rowena Spencer. The spherical theory

espoused by Dr. Spencer postulates that two monovulvar embryonic discs lie adjacent to each other either floating on the outer surface (yolk sac) or inner surface (amniotic cavity) of a sphere (10) (Figs. 109-1 and 109-2). The embryonic discs may unite in any one of several orientations. The union, however, is always homologous. Fusion between two embryonic discs cannot occur at random surfaces of the disc. Union can only occur where surface ectoderm is either absent or destined to break down, such as in the oropharyngeal and cloacal membranes or along the neural tube. Ventral union (union involving the yolk sac and the periphery of the disc) leads in general to twins sharing one abdomen and one umbilicus, whereas dorsal union (neural tube) leads to twins with separate abdomens and two umbilical cords.

espoused by Dr. Spencer postulates that two monovulvar embryonic discs lie adjacent to each other either floating on the outer surface (yolk sac) or inner surface (amniotic cavity) of a sphere (10) (Figs. 109-1 and 109-2). The embryonic discs may unite in any one of several orientations. The union, however, is always homologous. Fusion between two embryonic discs cannot occur at random surfaces of the disc. Union can only occur where surface ectoderm is either absent or destined to break down, such as in the oropharyngeal and cloacal membranes or along the neural tube. Ventral union (union involving the yolk sac and the periphery of the disc) leads in general to twins sharing one abdomen and one umbilicus, whereas dorsal union (neural tube) leads to twins with separate abdomens and two umbilical cords.

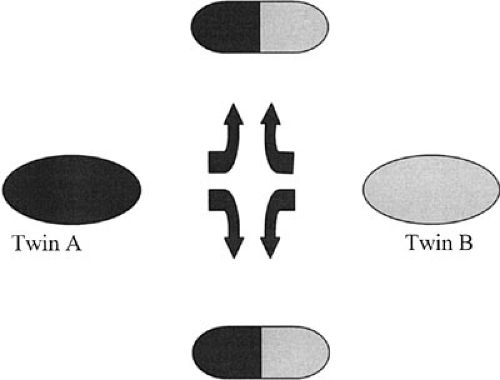

The development of certain types of twins may require what are termed adjustments to conjunction (11). These include division and diversion of midsaggital structures and aplasia of contiguous lateral anlagen. Division and diversion is best illustrated by cephalopagus twins. In this case as the oropharyngeal membrane fuses, it splits sagitally and diverts laterally to fuse with its compliment from the other twin (Fig. 109-3). In the case of cephalopagus twins, this results in a child with two faces, one on each side of the head, but one-half of each face is derived from each twin. This is supported by the neuroanatomy of these twins in which the brain is also found to split in a similar manner (11).

Aplasia is best demonstrated in parapagus twins. In this case, twins are fused laterally and, by an unexplained mechanism, the midline structures in the area of conjoinment disappear. These children may have two heads, but only one trunk and one set of legs. The arms and legs that lay centrally in the area of fusion fail to develop.

TERMINOLOGY

The terminology of conjoined twins may be confusing because there are many terms in the literature. Classification of the types of twins is based on anatomic description and describes the most prominent area of conjoinment. Confusion may arise because of a continuum between some of these twins, such as the thoracopagus and omphalopagus twins. The Greek term -pagus means to be fixed or joined with the prefix describing the area where the twins are joined. One frequently used classification system by Potter and Craig lists five major categories, omphalopagus or xiphopagus (umbilicus), thoracopagus (chest), ischiopagus (hip), craniopagus (helmet), and pygopagus (rump) (12). Spencer adds the additional categories of parapagus (side), cephalopagus (head), and rachipagus (spine) (13). In addition, parasites (teratomas and fetus-in-fetu) may be considered part of this process. Several suffixes are descriptive of certain areas of the body -prosopus (face), -brachius (upper limb), and -pus (lower limbs). The other

terms needed are -di, -tri, and tetra, to describe the number of the previous structures present (e.g., ischiopagus tetrapus).

terms needed are -di, -tri, and tetra, to describe the number of the previous structures present (e.g., ischiopagus tetrapus).

When discussing conjoined twins, it is important to use uniform terminology in describing structures shared between twins and structures that are completely separate. “Anterior” and “posterior” are not terms that apply to individual twins, but are used as points of reference looking at the twins as a whole. Twins lying in a position such that the abdomen is most fully exposed have this aspect identified as the secondary anterior and the opposite side as the secondary posterior. Using this anterior aspect as a reference, twins may then be identified as the “twin on their right,” or right twin and the “twin on their left,” or left twin. Structures in individual twins are identified as dorsal and ventral rather than anterior and posterior. This nomenclature tends to work for all conjoined twins, with the exception of craniopagus and rachipagus twins (13).

CLASSIFICATION AND ANATOMY

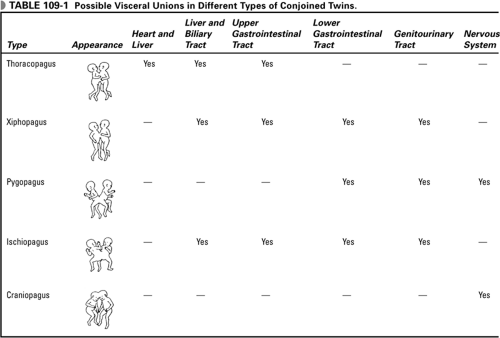

The various types of twins and the organ systems shared are listed in Table 109-1. There are two basic sets of conjoined twins, each set representing a continuum of fusion, either ventral to ventral or dorsal to dorsal. When the twins face each other, the union ranges from fusion at the rostral and midventral levels, such as in cephalopagus infants, to the caudal and caudolaterally fused infants, such as ischiopagus and parapagus infants. The infants in this continuum share some common aspect of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and most share a single umbilicus. The second basic set involves twins conjoined at the neural tube and craniovertebral axis. These infants face away from each other and have separate umbilical cords and GI tracts. The critical anatomic point that is key in determining separability for either set of twins is the degree of union of vital organs, especially the heart and central nervous system (CNS). When there is one heart for two infants or there is significant union of the CNS, it is unlikely that both or even one infant will survive surgical separation.

The most common type of conjoined twins is thoracopagus twins, comprising 40% of all such infants. Frequently, they are classified with omphalopagus twins and together these two types account for ∼75% of these infants (14). For purposes of clinical discussion, however, it is best to consider these two types separately because, although omphalopagus twins can usually be separated, thoracopagus twins usually cannot. Thoracopagus twins share the heart in more than 75% of cases, and it is this union that usually makes separation difficult or impossible and survival of both twins extremely unlikely (15). Survival of even one twin when the heart is fused is unusual (Table 109-2). The pericardial sac is shared in 90% of thoracopagus twins, the biliary tree in 22%, and the upper GI tract in 50%. The

stomach and esophagus may be shared on occasion, but union usually starts at the level of the distal duodenum and ends near the level of a Meckel’s diverticulum (14). These infants almost always have a shared bridge of the liver between them and union of the biliary tree should be suspected if the infants have a common duodenum at the area of the ampulla of Vater.

stomach and esophagus may be shared on occasion, but union usually starts at the level of the distal duodenum and ends near the level of a Meckel’s diverticulum (14). These infants almost always have a shared bridge of the liver between them and union of the biliary tree should be suspected if the infants have a common duodenum at the area of the ampulla of Vater.

TABLE 109-2 Survival Rates for Conjoined Twins. | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Omphalopagus (also called xiphopagus) twins account for ∼35% of conjoined twins (14). These children also face each other and share a common umbilicus, but the heart is never joined. They tend to be the least complicated infants to separate. The union usually extends from the xiphoid to the umbilicus and an omphalocele may be present. There is usually a connecting bridge of liver and the diaphragm is likely shared, but the upper GI tract is usually separate.

Twenty percent of conjoined twins are pygogagus, and only 7% of the typical cases are boys (16). These twins face away from each other and have a separate umbilicus. They are joined at the sacrum, buttocks, and perineum. Most commonly, there are two sets of external genitalia united back to back in the area of the forchette in girls. Typically, the urethral orifice is separate, although when junction is more extensive, the vagina and urethra may become fused. The anus is usually single and empties posterior to the urogenital fusion. The GI tracts are for the most part separate, but unite at the rectum several centimeters proximal to the anal canal. Twenty five percent of pygopagus twins have renal anomalies, including renal agenesis, ectopia, and fusion. Forty percent of these twins share a single dural mater, and there may be a fused or continuous spinal cord (16). The pelvic rings are separate with the osseous fusion involving the lateral portion of the sacrum and coccyx. Almost one-half of these twins have significant anomalies of the CNS and/or vertebral column, including hydrocephalus, myelomeningocele, spina bifida, and rachischisis (16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree