Colon

James D. Geiger

University of Michigan, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109–0245.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

The primitive gut, which is divided into the foregut, the midgut, and the hindgut, develops during the fourth week of gestation. The midgut develops into the small intestine (beginning at the entrance of the common bile duct), and the large intestine develops proximal to the midtransverse colon. This intestinal segment receives blood from the superior mesenteric artery. The hindgut develops into the large bowel distal to the midtransverse colon, as well as the proximal anus and the lower urogenital tract, and receives its main blood supply from the inferior mesenteric artery.

The developing midgut migrates out of the abdominal cavity during the sixth week of pregnancy. During the ensuing 4 weeks, the midgut rotates 270 degrees in a counterclockwise direction about the superior mesenteric artery before assuming its final anatomic position in the abdominal cavity, which leaves the cecum positioned in the right side of the abdomen.

Anatomy

The colon is a tubular structure approximately 30 to 40 cm in length at birth that reaches 1.5 m in length in the adult. It is continuous with the small intestine at the ileocecal valve proximal and ends distally at the anal verge. The external appearance of the colon is differentiated from the small bowel because of differences in their musculature. Although both organs have inner circular and outer longitudinal muscle layers, the colonic longitudinal muscle fibers coalesce into three discrete bands, termed teniae, located at 120-degree intervals about the colonic circumference. The teniae start at the base of the appendix and run continuously to the proximal rectum and are important for identification of the colon during surgery. Outpouchings of the colon (haustra) separate the teniae. The folds between the haustra have a semilunar appearance when viewed from within the colon. On the outside of the colon are fatty-filled sacs of peritoneum called appendices epiploicae or omental appendices; these are more prominent in older children and in children with obesity.

The first portion of the colon, the cecum, lies in the right iliac fossa, and is slightly dilated compared with the rest of the colon. The cecum is more mobile in neonates, even with normal rotation, and may be located toward the right upper abdomen. The vermiform appendix is a blind outpouching of the cecum that begins inferior to the ileocecal valve. The ascending colon extends cranially from the cecum along the right side of the peritoneal cavity to the undersurface of the liver. In most individuals, the mesentery of the ascending colon has fused with the parietal peritoneum, making this segment of the colon a retroperitoneal structure. At the hepatic flexure, the colon turns medially and anterior to emerge into the peritoneal cavity as the transverse colon, which supports the greater omentum. The transverse colon can be quite mobile on its mesentery, even dropping below the pelvic brim before reaching its attachment to the diaphragm at the splenic flexure. The descending colon travels posterior and then inferior in the retroperitoneal compartment to the pelvic brim. There it reemerges into the peritoneal cavity as the sigmoid colon. This is an S-shaped segment of variable length. Its mobility and tortuosity can be a challenge during endoscopy, also causing it to be susceptible to volvulus.

The arterial supply to the colon is derived from the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. The superior mesenteric artery provides the blood supply to the colon from the ileocecal area to the distal third of the transverse colon. The cecum is supplied by the anterior and posterior cecal arteries, the ascending colon by the ileocolic and right colic branches, and the transverse colon by the middle colic artery. The distal transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon are all supplied by the superior and inferior

left colic branches of the inferior mesenteric artery. There is communication among arterial branches through the marginal arteries, which extend from the ileocolic junction to the distal sigmoid colon (Fig. 88-1).

left colic branches of the inferior mesenteric artery. There is communication among arterial branches through the marginal arteries, which extend from the ileocolic junction to the distal sigmoid colon (Fig. 88-1).

ANATOMIC CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Colonic Atresia

Of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract atresias, only gastric atresia is more uncommon than colonic atresia. Acquired obstruction of the colon, usually secondary to necrotizing enterocolitis, is significantly more common than congenital atresia. Isolated colonic atresia may be associated with ophthalmologic defects, skeletal anomalies, jejunal atresia, aganglionosis, and abdominal wall defects. Colonic atresia presents as distal intestinal obstruction in the neonate, with abdominal distention, bilious emesis, and absent passage of meconium (1,2). It must be differentiated from other causes of ileal or colonic obstruction. Contrast enema is useful in the evaluation of these neonates, revealing a distal microcolon with incomplete colonic filling. Importantly, in neonates with clinically apparent small bowel atresia, either a contrast enema or intraoperative evaluation of the colon must be completed to rule out a concurrent more distal obstruction such as colonic atresia (Fig. 88-2). Failure to establish distal patency produces a predictable postoperative failure.

Optimal management techniques are determined by the location of the colon atretic segment, as well as other medical problems. Generally, simple atresia of the colon is managed by limited segmental resection of the dilated proximal segment and with primary end-oblique anastomosis. Rarely, exteriorization as a colostomy with distal mucous fistula is employed because of prohibitive luminal discrepancy, if there are concerns about abnormalities in vascularity or innervation adjacent to the atretic segment, or if the patient has other confounding medical risks.

ROTATIONAL ANOMALIES

Abnormalities of intestinal rotation represent a spectrum of incomplete or nonrotation of either (or both) the duodenojejunal or cecocolic intestinal limb and are discussed in detail elsewhere (see Chapter 87). With reverse rotation, the duodenum and jejunum lie anterior to the superior mesenteric vessels, which may then obstruct the posteriorly placed transverse colon. This can result in chronic colonic obstruction, which requires reflection of the colon and reversal of the rotation. Cecal volvulus, with associated obstruction and distention, results from lax fixation of the right colon and cecum in the retroperitoneum, leading to a freely mobile cecum. Ninety percent of patients with cecal volvulus have a full axial volvulus; 10% have a cecal bascule (cecum folded on itself in an anterior cephalad direction). Treatment includes reduction of the volvulus, followed generally by resection and possibly by fixation.

Sigmoid volvulus is the most common form of colonic volvulus and typically results from acquired redundancy of

the sigmoid colon mesentery in children with chronic constipation and neurologic disorders such as cerebral palsy. Plain abdominal radiographs may be diagnostic. The dilated sigmoid appears as an inverted dilated U-shaped, sausagelike intestinal loop. Water-soluble contrast enema may be diagnostic, but should not be performed on patients with suspected colonic necrosis. Reduction of the volvulus may occur during the examination. If necrosis or perforation is suspected, reduction should not be attempted, and the patient should undergo emergency laparotomy. If peritonitis is not apparent, rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy should be performed in an attempt to reduce the volvulus. Unsuccessful detorsion, bloody discharge, or evidence of mucosal ischemia indicates strangulation or necrosis, and the patient should undergo emergency exploration.

the sigmoid colon mesentery in children with chronic constipation and neurologic disorders such as cerebral palsy. Plain abdominal radiographs may be diagnostic. The dilated sigmoid appears as an inverted dilated U-shaped, sausagelike intestinal loop. Water-soluble contrast enema may be diagnostic, but should not be performed on patients with suspected colonic necrosis. Reduction of the volvulus may occur during the examination. If necrosis or perforation is suspected, reduction should not be attempted, and the patient should undergo emergency laparotomy. If peritonitis is not apparent, rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy should be performed in an attempt to reduce the volvulus. Unsuccessful detorsion, bloody discharge, or evidence of mucosal ischemia indicates strangulation or necrosis, and the patient should undergo emergency exploration.

PHYSIOLOGY

The colon is much more than a receptacle and conduit for the end products of digestion. It absorbs water, sodium, and chloride, and secretes potassium, bicarbonate, and mucus. In addition, it is the site of digestion of certain carbohydrates and proteins and provides the environment for the bacterial production of vitamin K.

Water and Electrolyte Exchanges.

The major absorptive function of the colon is the final regulation of water and electrolyte balance in the intestine. The colon reduces the volume of enteric contents by absorbing greater than 90% of the water and electrolytes presented to it.

Sodium and Potassium.

The colon is able to absorb sodium against very high concentration gradients, especially the distal colon, which shares many basic cellular mechanisms of sodium and water transport with the distal convoluted tubule of the kidney, including the ability to respond to aldosterone. A patient with an ileostomy loses this absorptive capacity and may not tolerate increased sodium losses or decreased sodium intake (3). Potassium transport in the colon is mainly passive, along an electrochemical gradient generated by the active transport of sodium.

Chloride and Bicarbonate.

Chloride, like sodium, is actively absorbed across the colonic mucosa against a concentration gradient. Chloride and bicarbonate are

exchanged at the luminal border. Chloride absorption is facilitated by an acidic environment, and the secretion of bicarbonate is enhanced by increased concentration of luminal chloride.

exchanged at the luminal border. Chloride absorption is facilitated by an acidic environment, and the secretion of bicarbonate is enhanced by increased concentration of luminal chloride.

Short-chain Fatty Acids.

Although active absorption of nutrients is minimal, the colon can passively absorb short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) formed by intraluminal bacterial fermentation of unabsorbed carbohydrates, particularly fiber. The absorbed SCFAs butyrate, acetate, and propionate are the major fuel sources of the colonic epithelium. They provide the energy required for active sodium transport, and altered SCFA metabolism or SCFA deficiency may result in impaired colonic sodium absorption. There is evidence that SCFA metabolism is impaired in patients with ulcerative colitis and that intraluminal infusion of SCFAs can be of benefit in patients with colitis. SCFAs have also been shown to be effective in treating diversion colitis (which can occur after a diverting ileostomy or colostomy) (4).

Diarrhea.

A number of agents can stimulate fluid and electrolyte secretion in the colon, including bacteria, enterotoxins, hormones, neurotransmitters, and laxatives. Gut hormones, particularly vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, have been shown to have significant effects on colonic absorption and secretion. Prostaglandins play a role in the pathogenesis of diarrhea associated with ulcerative colitis and several laxatives. Bile salt malabsorption after terminal ileal resection and long-chain fatty acid malabsorption in steatorrhea are clinically important examples of secretory diarrhea induced by colonic mucosal inflammation. The colonic mucus and fluid are high in potassium and may result in potassium depletion in chronic cases.

Colonic Microflora.

The human colon is sterile at birth, but is colonized within a matter of hours from the environment in an oral to anal direction. Bacteroides, destined to be the dominant bacteria in the colon, is first noted at about 10 days after birth. By 3 to 4 weeks after birth, the characteristic stool flora is established and persists into adult life. The large intestine harbors a dense microbial population, with bacteria accounting for approximately one-third of the dry weight of feces. Each gram of feces contains 1011 to 1012 bacteria, with anaerobic bacteria outnumbering aerobic organisms by a factor of 102 to 104. Bacteroides species are the most common colonic organisms, present in concentrations of 1011 to 1012 organisms per milliliter of feces. The complex and important symbiotic relationship between humans and colonic bacteria is not completely defined, but it is recognized that endogenous colonic bacteria suppress the emergence of pathogenic microorganisms, play an important role in the breakdown of carbohydrates and proteins that escape digestion in the small bowel, participate in the metabolism of numerous substances that are salvaged by the enterohepatic circulation (including bilirubin, bile acids, estrogen, and cholesterol), and produce certain beneficial elements such as vitamin K (5).

CHRONIC IDIOPATHIC INTESTINAL PSEUDOOBSTRUCTION

Chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudoobstruction (CIP) is a clinical syndrome defined by the presence of signs and symptoms characteristic of intestinal obstruction in the absence of anatomic obstruction (6). Patients most frequently present with abdominal pain and distention, failure to thrive, and vomiting and constipation. Most cases are congenital and of either myopathic or neuropathic origin (rarely both). Most are sporadic, with no obvious family history. Histologic findings can include muscle fibrosis, vacuolar degeneration and disorganization of myofilaments, maturational arrest of myenteric plexuses, neuronal intestinal dysplasia, or a completely normal intestinal wall. In addition to these idiopathic cases, pseudoobstruction can be seen in association with Down syndrome, neurofibromatosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B, Russell-Silver syndrome, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, acute viral gastroenteritis, and extreme prematurity.

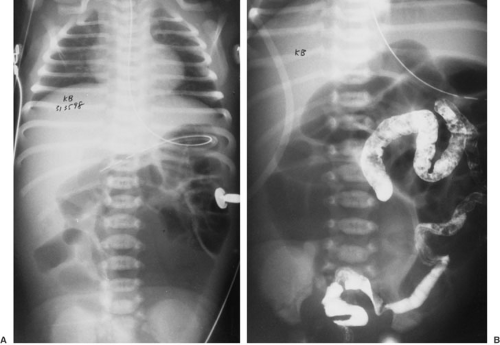

The clinical presentation is one of abdominal distention and vomiting (Fig. 88-3). More than one-half of affected infants develop symptoms within a few days of birth. Of these, about 40% have associated malrotation. Some less severely affected infants present with vomiting and failure to thrive within the first few months of life. Notably, more than three-fourths of affected infants present during the first year of life. Although laparotomy for biopsy alone is not indicated, many of these children undergo surgery for treatment of malrotation or evaluation of intestinal obstruction. When this scenario develops a full-thickness, biopsy of bowel wall should be obtained. The tissues should be processed for conventional histology, appropriate histochemistry, electron microscopy, and silver stains to evaluate for myopathic or neuropathic processes.

Although CIP is a clinical diagnosis, manometric studies can be useful in documenting abnormalities in amplitude or coordination of contractions. Esophageal, antroduodenal, colonic, and anorectal manometry can help determine the site and type of pseudoobstruction and assist in evaluating the response to therapy. Contemporary prokinetic drugs may be helpful, but are not sufficient in most affected children. Erythromycin is not effective for generalized motility disorders or those with isolated colonic involvement, but can bring relief in neuropathic gastroparesis. Nutritional support is vital because the clinical course is often characterized by unpredictable remissions and exacerbations, and malnutrition can result. Most

children tolerate all or some of their nutrition enterally, and this is desirable because it is less morbid than parenteral nutrition. Surgery should play a limited role in the long-term treatment of CIP, although one or more laparotomies are common prior to establishing the diagnosis. Even though gastrostomy tube placement can be useful in allowing a convenient access for long-term tube feeding or venting, other procedures, such as fundoplication, pyloroplasty, or gastrojejunostomy, have proved less useful. Colectomy has been helpful in a few children with isolated colonic pseudoobstruction (7). Prolonged postoperative ileus is to be expected in these patients, and the development of adhesions makes evaluation of future episodes of acute pseudoobstruction increasingly difficult. Almost all mortality is related to complications of total parenteral nutrition (8).

children tolerate all or some of their nutrition enterally, and this is desirable because it is less morbid than parenteral nutrition. Surgery should play a limited role in the long-term treatment of CIP, although one or more laparotomies are common prior to establishing the diagnosis. Even though gastrostomy tube placement can be useful in allowing a convenient access for long-term tube feeding or venting, other procedures, such as fundoplication, pyloroplasty, or gastrojejunostomy, have proved less useful. Colectomy has been helpful in a few children with isolated colonic pseudoobstruction (7). Prolonged postoperative ileus is to be expected in these patients, and the development of adhesions makes evaluation of future episodes of acute pseudoobstruction increasingly difficult. Almost all mortality is related to complications of total parenteral nutrition (8).

FIGURE 88-3. Supine (A) and decubitus (B) abdominal radiographs of a child with chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudoobstruction demonstrate marked bowel distension. |

A relatively well-defined subset of CIP patients includes neonates with megacystis-microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. This rare cause of functional neonatal intestinal obstruction is associated with hypoperistalsis, malrotation, dilated proximal ileum, narrow distal ileum and colon, and bladder distention. The cause of this syndrome is unknown, but possible mechanisms include visceral myopathy, imbalance in gut peptides, defective autonomic inhibitory neuroeffector activity, and destruction of hollow viscus smooth muscle and neural network by an in utero intramural inflammatory process with resultant fibrosis. This disorder appears to be autosomal recessive and is usually lethal; most deaths occur within the first year of life. Mortality is primarily related to complications of total parenteral nutrition, including sepsis, liver disease, and catheter complications. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis allows counseling in subsequent pregnancies in affected families (9,10).

COLITIS

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Although more than 60% of neonates may be colonized with Clostridium difficile,it is usually asymptomatic due to immaturity of the neonatal intestine receptor sites for C. difficile toxins (11). Pseudomembranous colitis is the most common clinical presentation and is almost invariably caused by toxin-producing C. difficile infection after antibiotic usage. Toxigenic Clostridium perfringens type C and Shigella dysenteriae type 1 may also be responsible for the development of pseudomembranous colitis. Nearly all

antimicrobial agents have been implicated in the disorder, including antifungal, antiviral, and antimicrobial agents to which C. difficile is susceptible, including vancomycin and metronidazole. Pseudomembranous colitis has also been reported in infants whose only exposure to antibiotics was through breast milk. The risk of development appears unrelated to the dose or duration of antibiotic treatment. The protection against C. difficile proliferation provided by normal intestinal flora can be disrupted by antibiotic usage, increasing susceptibility to pseudomembranous colitis (12,13).

antimicrobial agents have been implicated in the disorder, including antifungal, antiviral, and antimicrobial agents to which C. difficile is susceptible, including vancomycin and metronidazole. Pseudomembranous colitis has also been reported in infants whose only exposure to antibiotics was through breast milk. The risk of development appears unrelated to the dose or duration of antibiotic treatment. The protection against C. difficile proliferation provided by normal intestinal flora can be disrupted by antibiotic usage, increasing susceptibility to pseudomembranous colitis (12,13).

The pathogenicity of C. difficile is due to its production of toxins. Toxin A is an enterotoxin that binds to receptors on the mucosal epithelial surface, resulting in severe inflammation and fluid secretion. Toxin B is a cytotoxin that induces alterations in cell shape and causes diffuse enterocyte cell damage. Although the production of toxin is necessary for the development of colitis, the titer of toxin found in a patient’s stool does not necessarily correlate with the severity of disease. Extraintestinal circulation of toxin after mucosal and submucosal invasion may be responsible for the shock state and sudden death that infrequently accompany severe disease.

Pseudomembranous colitis most frequently presents with mild to moderate, watery, nonbloody diarrhea beginning 7 to 10 days after the initiation of antibiotics, although the spectrum of disease can vary widely. Some patients present with fulminant disease and an acute abdomen with signs of toxic megacolon or perforation, even in the absence of preceding diarrhea. It is frequently among the potential diagnoses in patients evaluated for surgical disease, so it is essential for surgeons to be knowledgeable of its clinical features. In unrecognized and untreated catastrophic disease, mortality rates are as high as 20%. The diagnosis should also be considered in any child with a severe, protracted course of debilitating diarrhea, especially after antibiotic treatment. The diagnosis can be established by visualizing classic yellowish white, plaquelike pseudomembranes on endoscopy. More frequently, the diagnosis is made noninvasively in the appropriately suspicious clinical setting. Plain films of the abdomen may reveal “thumbprinting,” reflecting a markedly edematous colonic wall. Computed tomography of the abdomen may demonstrate colonic wall thickening and inflammation. The most sensitive method to establish a diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis is by C. difficile toxin detection. The most accurate method of toxin detection remains the cytotoxin tissue culture assay. The latex agglutination test is less reliable, although it can be used as a rapid screening test (14).

Patients who have mild pseudomembranous colitis, typically with fever, mild abdominal pain, and diarrhea, may respond to discontinuation of the implicated antibiotic. In more severe disease, treatment should include oral vancomycin, 40 mg per kg per day in three divided doses, or metronidazole, 20 to 30 mg per kg per day in three divided doses, continued for 7 to 10 days. The addition of this specific therapy allows for continued treatment with the inducing antibiotic, if necessary. Enteral administration of these therapeutic antibiotics, including by rectal or stomal irrigation if the oral route is unavailable, is much more effective than intravenous administration in reaching effective intraluminal concentrations. When parenteral therapy must be given, as with severe ileus, intravenous metronidazole achieves therapeutic fecal concentrations; intravenous vancomycin is less effective and does not reach adequate intraluminal concentrations. Relapse after treatment occurs in 10% to 20% of patients and is most often due to sporulation of C. difficile. These spores are resistant to treatment, and either longer courses of treatment or pulsed doses of antibiotics may be effective (12,15).

Children who have undergone definitive surgical treatment for Hirschsprung’s disease, have significantly prolonged carriage of C. difficile and may develop “post pull-through enterocolitis.” The cause of this increased sensitivity to pseudomembranous colitis is unclear. Because the clinical picture of C. difficile-associated pseudomembranous colitis can be indistinguishable from that of Hirschsprung’s enterocolitis, with fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, empiric but specific therapy should be started while awaiting results of stool evaluation in patients who are seriously ill (16,17).

ENTERIC INFECTIONS

Viral gastroenteritis is the second most common illness in the United States, where it accounts for 300 to 400 annual childhood deaths (18). Worldwide, viral gastroenteritis is responsible for more than 4 million childhood deaths per year. Rotavirus is responsible for more cases of diarrheal disease in infants and children than any other single cause. Norwalk virus and enteric adenoviruses are other relatively common viral pathogens that cause acute gastroenteritis. Rotavirus accounts for the winter peak in childhood gastroenteritis, whereas the enteric adenoviruses are responsible for the summer peak. Both tend to affect children younger than 2 years of age, are accompanied by significant diarrhea, and not uncommonly result in dehydration. Treatment is supportive; oral rehydration solutions are extremely useful and are often lifesaving in cases of dehydration.

Whereas viral agents invade villus enterocytes along the entire span of the small intestine, infecting bacterial agents often act in the colon. Several bacterial virulence mechanisms act specifically on the colon, causing cytotoxin injury, direct epithelial cell invasion, and enteroadhesive activity. Salmonella sp is the most common cause of bacterial diarrhea in children in the United States, and the incidence of this disease appears to be increasing. Because of the

invasiveness of this organism, infection can result in colitis and bacteremia, especially in patients with lymphoproliferative diseases and sickle cell anemia. Antibiotic treatment, with ampicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, is recommended in patients at high risk for the development of disseminated disease, those who appear septic, neonates, and those with complicated cases of gastroenteritis (19). Shigella sp is the second most common pathogen identified in cases of bacterial diarrhea in children and is an especially common cause of outbreaks of diarrhea in day-care settings. Although Shigella sp most frequently causes a mild, self-limited diarrhea, antibiotics are sometimes appropriate for patients who are severely ill to shorten the course of disease and to decrease the period of shedding of the organism. Nonpathogenic strains of Escherichia coli are among the most common bacteria in the normal flora of the human intestine, but pathogenic strains are an important cause of diarrheal disease. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli can occur in sporadic cases and in food-borne outbreaks. These bacteria produce a range of symptoms from watery diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis. Verotoxic serotype 0157:H7 is implicated in the development of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome, characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, uremia, and thrombocytopenia. It is the most common cause of acute renal failure in children. Antibiotic treatment does not hasten resolution of this disease, but aggressive, supportive measures are required because hemolytic-uremic syndrome is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates (20). Significant medical complications include encephalopathy, pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and seizures. Most patients can be treated successfully nonoperatively, but surgery may be required to support dialysis or for treatment of the acute abdomen with colonic microvascular injury leading to inflammation or necrosis. Acidosis, peritonitis, or obvious perforation or obstruction are reported and may require emergent colonic resection with or without diversion. Resection for late stenosis after resolution of the acute illness has also been reported (21).

invasiveness of this organism, infection can result in colitis and bacteremia, especially in patients with lymphoproliferative diseases and sickle cell anemia. Antibiotic treatment, with ampicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, is recommended in patients at high risk for the development of disseminated disease, those who appear septic, neonates, and those with complicated cases of gastroenteritis (19). Shigella sp is the second most common pathogen identified in cases of bacterial diarrhea in children and is an especially common cause of outbreaks of diarrhea in day-care settings. Although Shigella sp most frequently causes a mild, self-limited diarrhea, antibiotics are sometimes appropriate for patients who are severely ill to shorten the course of disease and to decrease the period of shedding of the organism. Nonpathogenic strains of Escherichia coli are among the most common bacteria in the normal flora of the human intestine, but pathogenic strains are an important cause of diarrheal disease. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli can occur in sporadic cases and in food-borne outbreaks. These bacteria produce a range of symptoms from watery diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis. Verotoxic serotype 0157:H7 is implicated in the development of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome, characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, uremia, and thrombocytopenia. It is the most common cause of acute renal failure in children. Antibiotic treatment does not hasten resolution of this disease, but aggressive, supportive measures are required because hemolytic-uremic syndrome is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates (20). Significant medical complications include encephalopathy, pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and seizures. Most patients can be treated successfully nonoperatively, but surgery may be required to support dialysis or for treatment of the acute abdomen with colonic microvascular injury leading to inflammation or necrosis. Acidosis, peritonitis, or obvious perforation or obstruction are reported and may require emergent colonic resection with or without diversion. Resection for late stenosis after resolution of the acute illness has also been reported (21).

GI manifestations of AIDS are often like bacterial colitis, with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Cytomegalovirus is the most common associated colonic pathogen and can cause necrotizing lesions that can lead to hemorrhage or perforation. Treatment with ganciclovir is often effective, although relapses are common (22).

Polyps and Polypsosis Syndromes

Juvenile Polyp

Solitary polyps of the colon are common during childhood, usually presenting with painless rectal bleeding. These lesions, known as juvenile polyps, are most commonly hamartomas; solitary adenomas are extremely rare. More than one polyp is found 40% to 50% of the time (23). The typical clinical presentation is intermittent, involving painless rectal bleeding or perianal polyp protusion between 2 and 5 years of age (24,25,26,27). The differential diagnosis of rectal bleeding is broad and includes anal fissure, Meckel’s diverticulum, vascular malformations, allergic enteropathy, colitis, and trauma. Juvenile polyps can be found throughout the colon, but are most common in the rectosigmoid region.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree