● COARCTATION OF THE AORTA

Definition, Spectrum of Disease, and Incidence

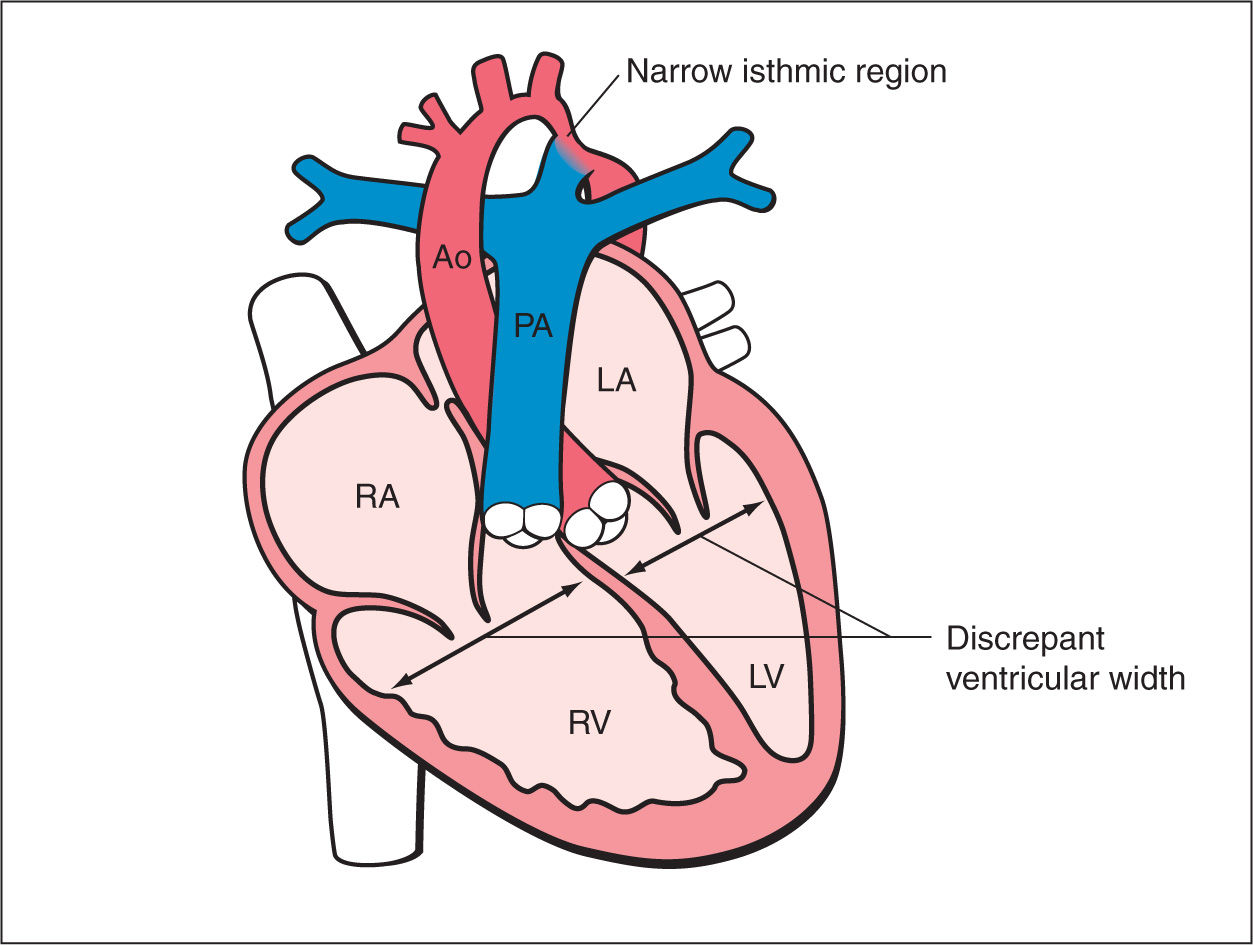

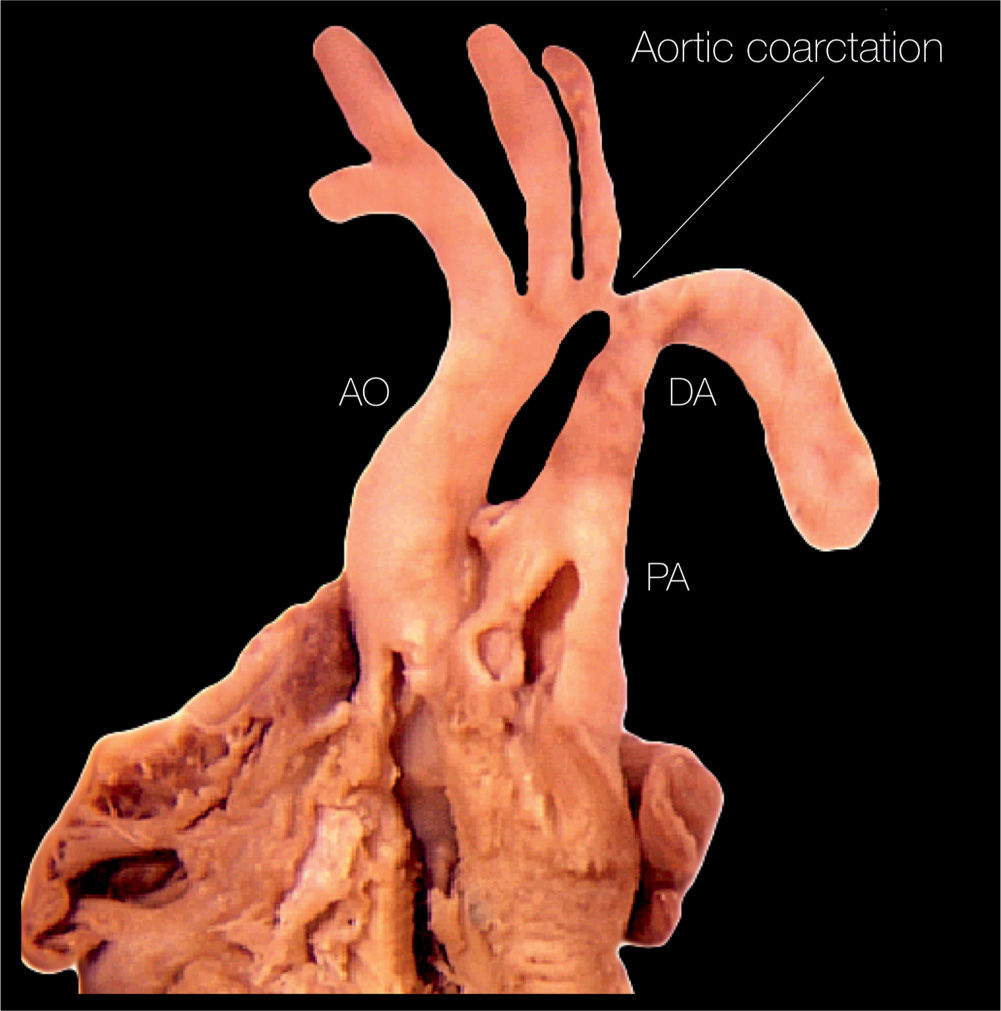

Coarctation of the aorta is a common anomaly, found in about 5% to 8% of newborns and infants with congenital heart disease (1, 2). Coarctation of the aorta involves narrowing of the aortic arch, typically located at the isthmic region, between the left subclavian artery and the ductus arteriosus (2) (Fig. 23.1). Alternatively, coarctation of the aorta may involve a long segment of the aortic arch, termed tubular hypoplasia of the aortic arch. Coarctation of the aorta occurs more commonly in boys, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.27 to 1.74 (3). The anomaly has a fairly high recurrence risk, between 2% and 6% for a previously affected child and 4% for an affected mother (4, 5). Chromosomal and extracardiac abnormalities are commonly associated with coarctation of the aorta (6). The embryologic origin of coarctation of the aorta is complex and not well understood, with two proposed concepts; the ductus tissue theory proposes that aortic constriction is due to migration of ductal smooth muscle cell into the aorta (7), whereas the hemodynamic theory proposes that coarctation results from reduced flow through the aortic arch in fetal life (8). Coarctation of the aorta can be classified as simple when it occurs without important intracardiac lesions and complex when it occurs in association with significant intracardiac pathology. When associated with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and aortic atresia, hypoplastic aortic arch should not be classified as coarctation of the aorta but rather as part of the main cardiac anomaly. Table 23.1 lists cardiac malformations that may include aortic coarctation or tubular aortic hypoplasia as part of the main cardiac anomaly. Figure 23.2 demonstrates coarctation of the aorta in an anatomic specimen of a fetal heart.

Figure 23.1: Schematic drawing of coarctation of the aorta. See text for details. RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; Ao, aorta.

Ultrasound Findings

Gray Scale

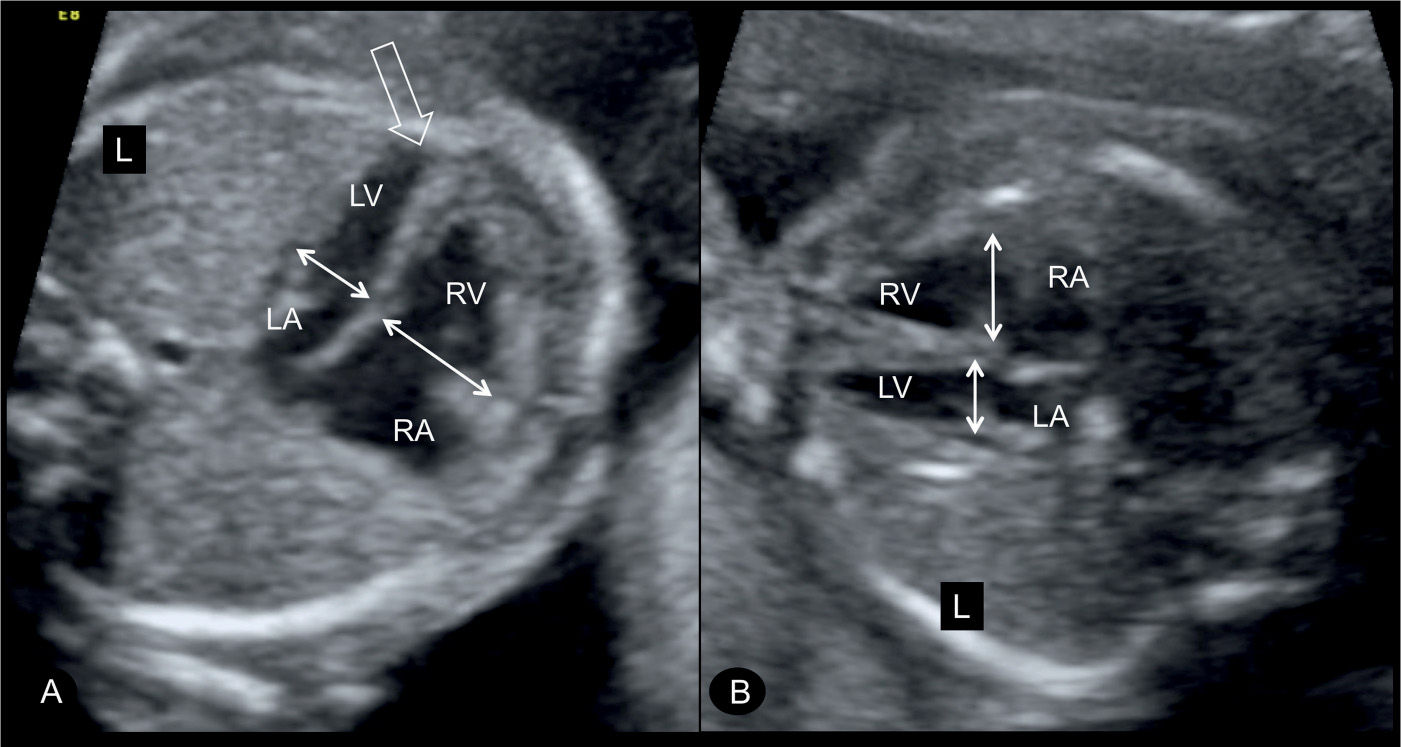

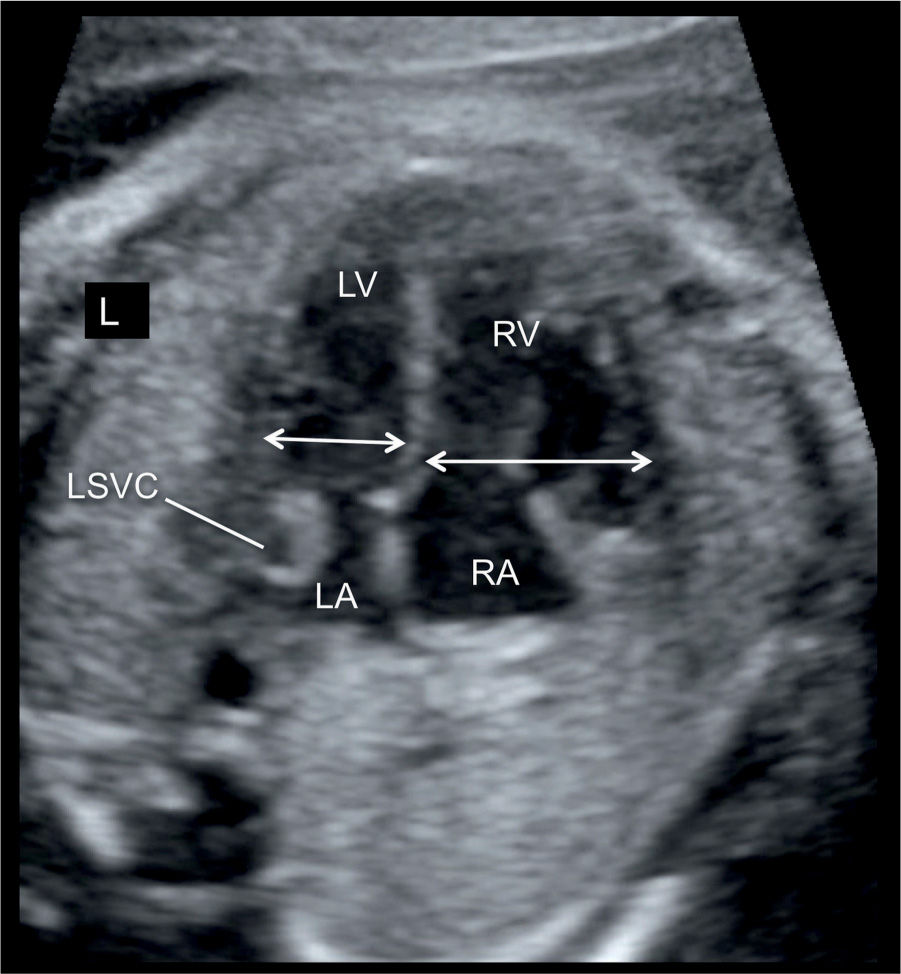

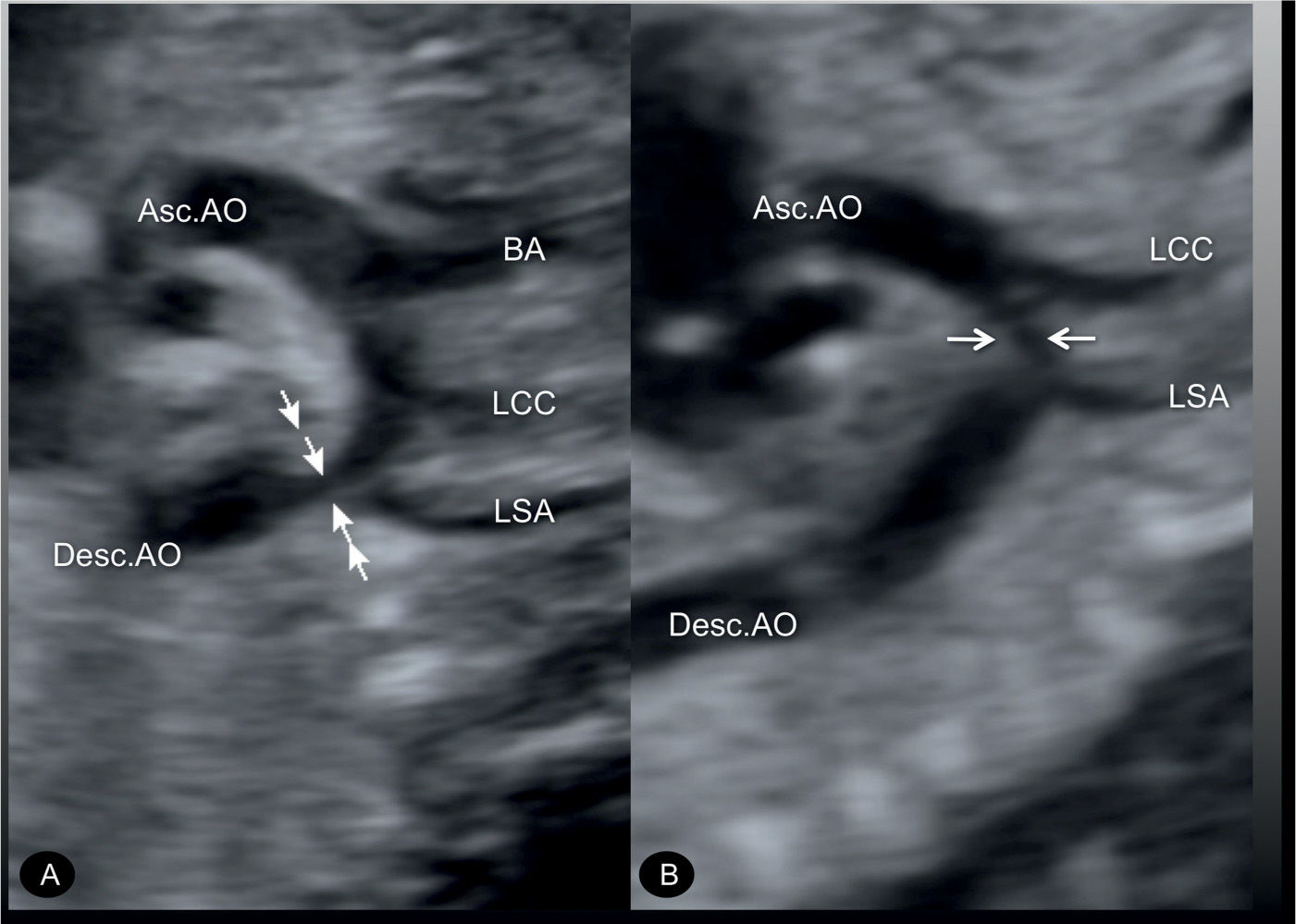

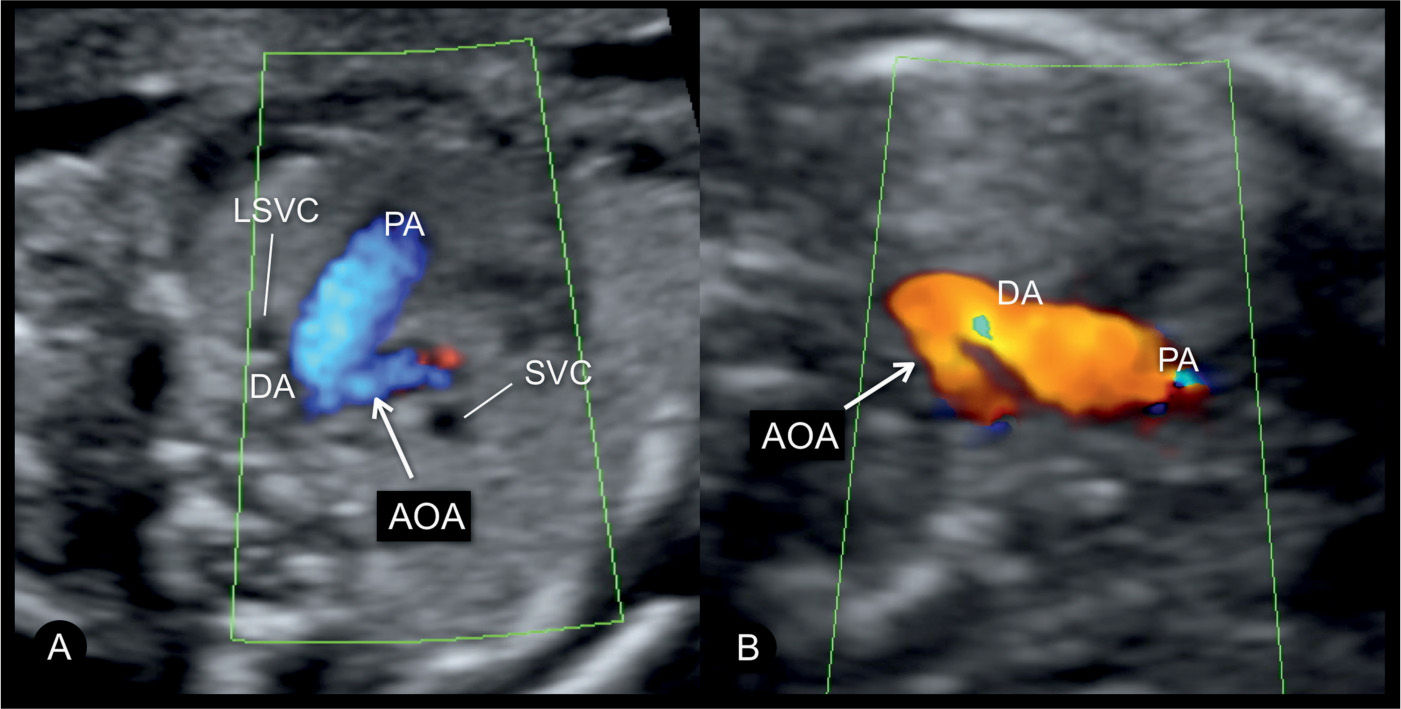

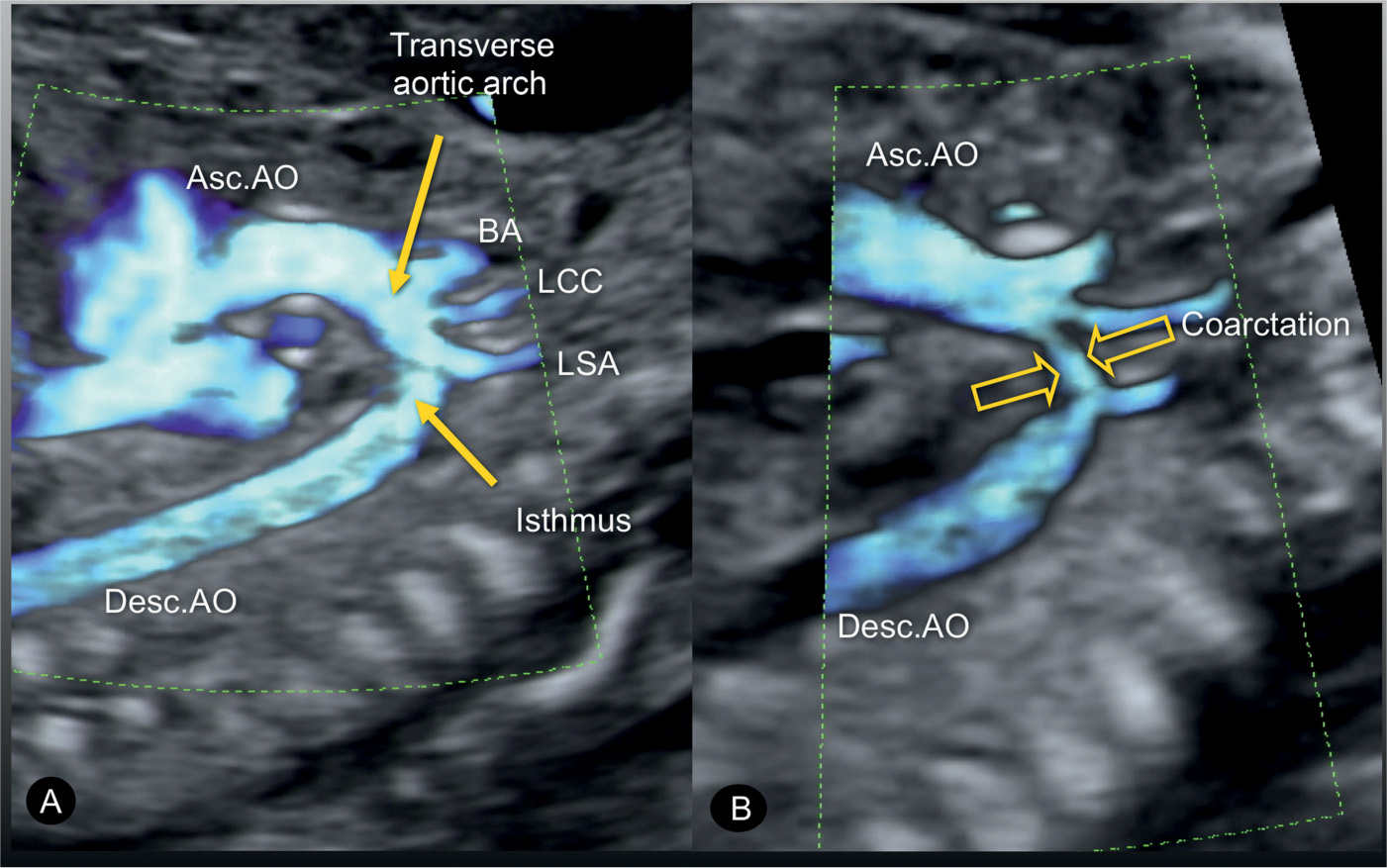

Ventricular disproportion is the leading sign for the suspicion of coarctation of the aorta in the four-chamber view. In this view, the left ventricle appears narrow when compared to the right ventricle (9–11) (Figs. 23.3 and 23.4). The ratio of right ventricular–to–left ventricular width, reported as 1.19 in normal fetuses, is at or greater than 1.69 in fetuses with coarctation of the aorta (12). Conversely to hypoplastic left heart syndrome, in coarctation of the aorta, the contractility of the left ventricle is normal and the mitral valve is patent (see also Chapter 22). Aortic coarctation in the fetus is occasionally seen in association with a persistent left superior vena cava (LSVC). In this association, a cross section of the LSVC can be seen at the level of the four-chamber view, bulging into the external border of the left atrium and resulting in narrowing of the inflow of the mitral valve (Fig. 23.4) (see also Chapter 31). The five-chamber view shows the ascending aorta with typically a normal diameter. The aortic root can be narrow on occasions, especially when a perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD) and/or aortic stenosis are present. The aortic valve is occasionally bicuspid, an anatomic finding that is difficult to diagnose antenatally. In the three-vessel-trachea view, the diameter of the transverse aortic arch, in a tangential section, is narrow when compared to the diameter of the main pulmonary artery (12), and this narrowing of the transverse aortic arch is most impressive in the isthmus region (Figs. 23.5 and 23.6). In the diagnosis of aortic coarctation, the three-vessel-trachea view, depicting the great vessel disproportion, is more specific than ventricular disproportion alone, noted on a four-chamber view. Occasionally in this plane, also a persistent LSVC can be found left to the pulmonary artery (Fig. 23.6). Once coarctation of the aorta is suspected in the transverse planes (four-chamber and three-vessel-trachea views), a longitudinal view of the aortic arch should be attempted. In this plane, the length and degree of the narrowing can be better assessed and the junction of the aortic isthmus and the ductus arteriosus with the descending aorta is better evaluated (Figs. 23.7 and 23.8, see also Color Doppler section). In this longitudinal view of the aortic arch, the narrowing is commonly located between the left subclavian artery and the origin of the ductus arteriosus. The aortic arch appears narrow and occasionally tortuous, termed contraductal shelf, an important clue for the presence of coarctation of the aorta (13). In the presence of severe coarctation of the aorta, the transverse arch between the left common and left subclavian arteries (Figs. 23.7B and 23.8) is elongated and narrow, and the left subclavian artery is found to arise at the junction of the ductus arteriosus with the descending aorta. Z-scores for the measurements of the size of the aortic isthmus, the transverse arch, and the angle between the aortic isthmus and the ductus arteriosus were proposed to improve the accurate description of this cardiac anomaly (14–16).

Cardiac Anomalies Associated with Coarctation of the Aorta or Tubular Aortic Hypoplasia |

• Unbalanced atrioventricular defect with a narrow left ventricle • Hypoplastic left heart syndrome • Double outlet right ventricle • Tricuspid atresia with ventricular septal defect and malposition of great vessels (type II) • Corrected transposition of the great arteries • Double inlet ventricle (single ventricle) |

Figure 23.2: Anatomic specimen of a fetal heart with coarctation of the aorta. Note the presence of aortic narrowing at the level of the aortic isthmus (labeled aortic coarctation). AO, aorta; PA, pulmonary artery; DA, ductus arteriosus.

Figure 23.3: Four-chamber view in two fetuses (A and B) with coarctation of the aorta showing the typical ventricular disproportions. The left ventricle (LV) is small in width when compared to the width of the right ventricle (RV) (double arrows). Note that the LV is apex forming (open arrow in A). RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; L, left.

Figure 23.4: Apical four-chamber view in a fetus with ventricular disproportion and coarctation of the aorta in combination with the presence of a persistent left superior vena cava (LSVC). The width of the left ventricle (LV) is smaller in comparison with the right ventricle (RV) (double arrows). A cross section of the LSVC can be seen at the border of the left atrium (LA). RA, right atrium; L, left.

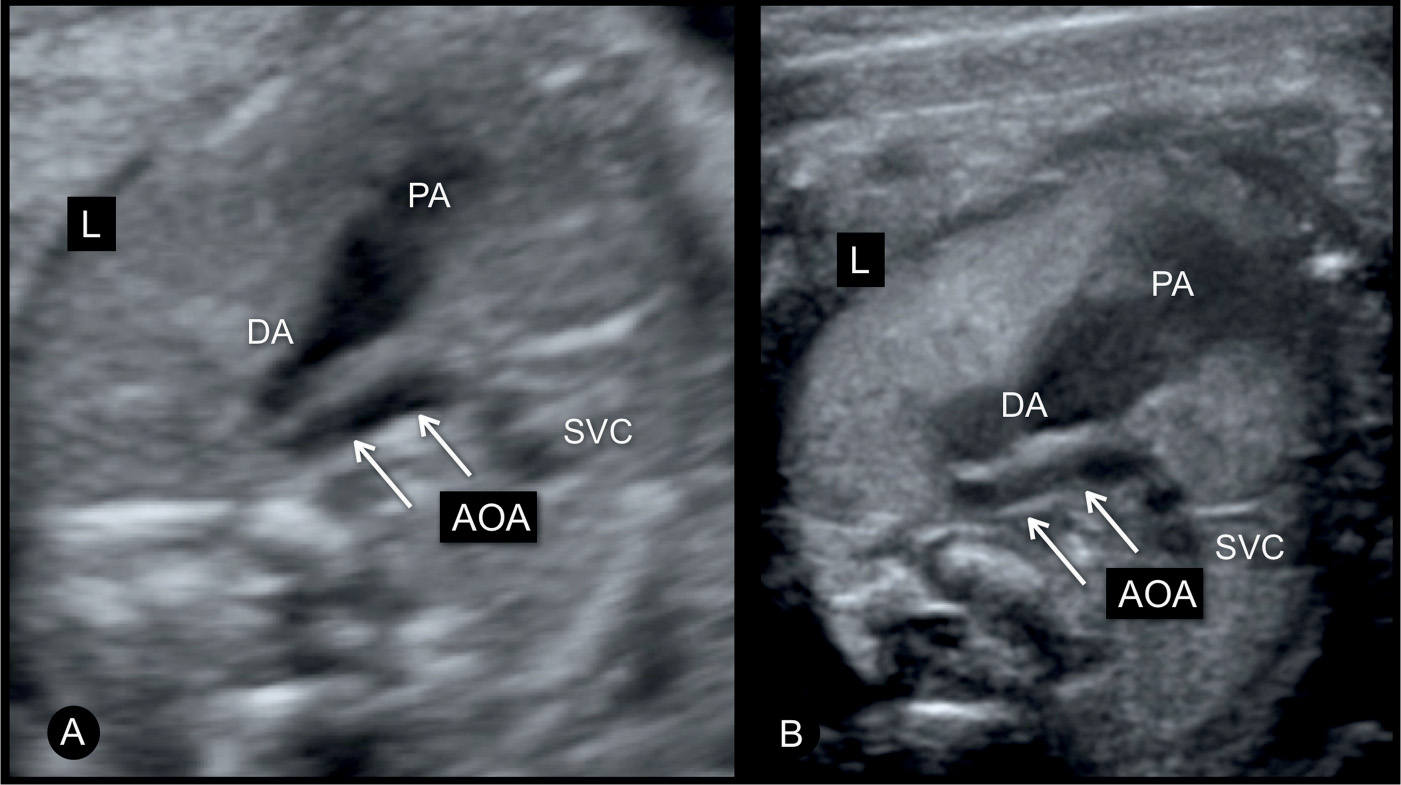

Figure 23.5: Three-vessel-trachea view in two fetuses (A and B) with moderate coarctation of the aorta. The transverse aortic arch (AOA) is narrow when compared to the size of the pulmonary artery (PA) and ductal arch (DA). The authors recommend lateral three-vessel-trachea views for better demonstration of small vessels in the upper chest. SVC, superior vena cava; L, left.

Figure 23.6: Three-vessel-trachea view in two fetuses (A and B) with severe coarctation of the aorta. Note the presence of tubular hypoplasia of the aortic arches (AOA) in A and B. A large segment of the transverse AOA is narrow when compared to the size of the pulmonary artery (PA) and ductal arch (DA). The fetus in B has a persistent left superior vena cava (LSVC). The presence of a LSVC increases the risk for aortic coarctation. SVC, superior vena cava; L, left.

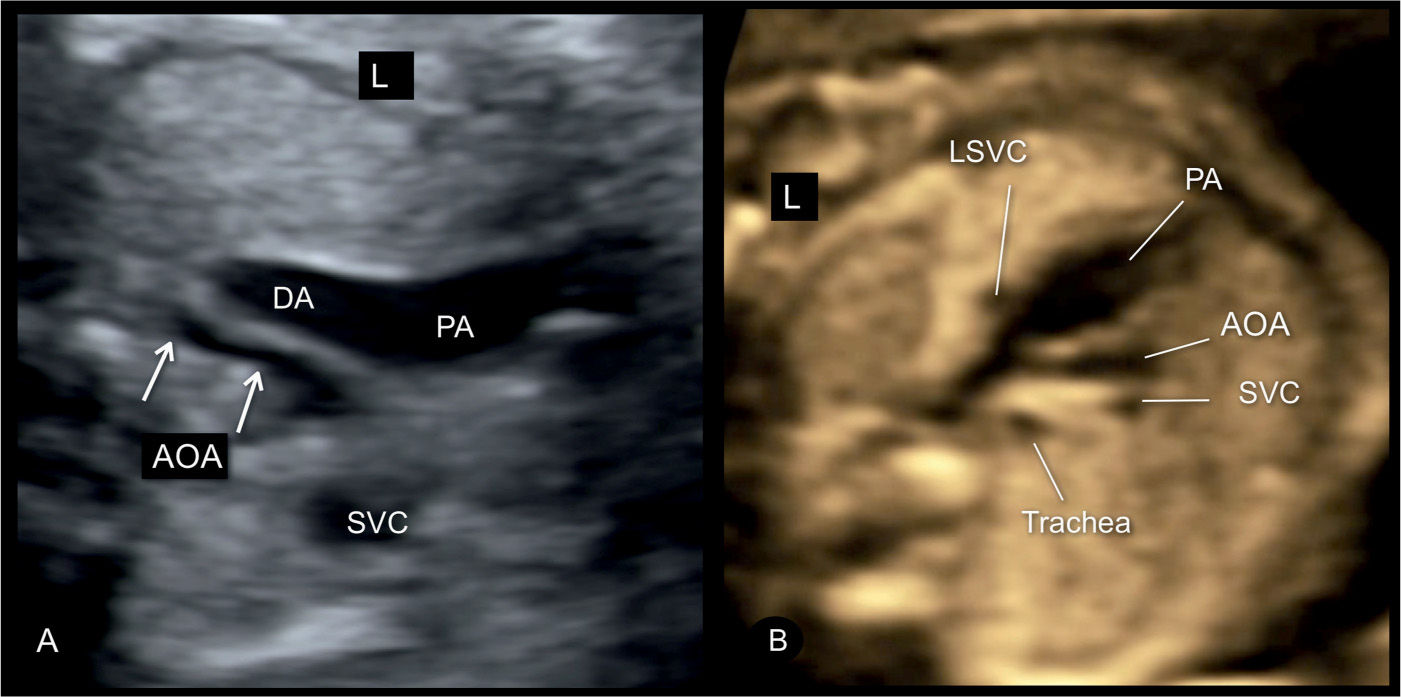

Figure 23.7: Sagittal views of the aortic arches in two fetuses (A and B) with coarctation of the aorta. In A, the narrowing is mainly in the aortic isthmic region (arrows) following the origin of the left subclavian artery (LSA). In B, the narrowing is in the middle portion of the transverse aortic arch (arrows) between the origins of the LSA and the left common carotid artery (LCC). Asc.AO, ascending aorta; Desc.AO, descending aorta; BA, brachiocephalic artery.

Figure 23.8: Sagittal view from the dorsal aspect of the aortic arch in a fetus with coarctation of the aorta in gray scale (A) and power Doppler (B). The narrowing is in the distal transverse aortic arch (short arrows) in the region of the left subclavian artery (LSA). The long yellow arrow points to the presence of a shelf, noted as a “shelf sign.” LCC, left common carotid artery; Desc.AO, descending aorta.

Color Doppler

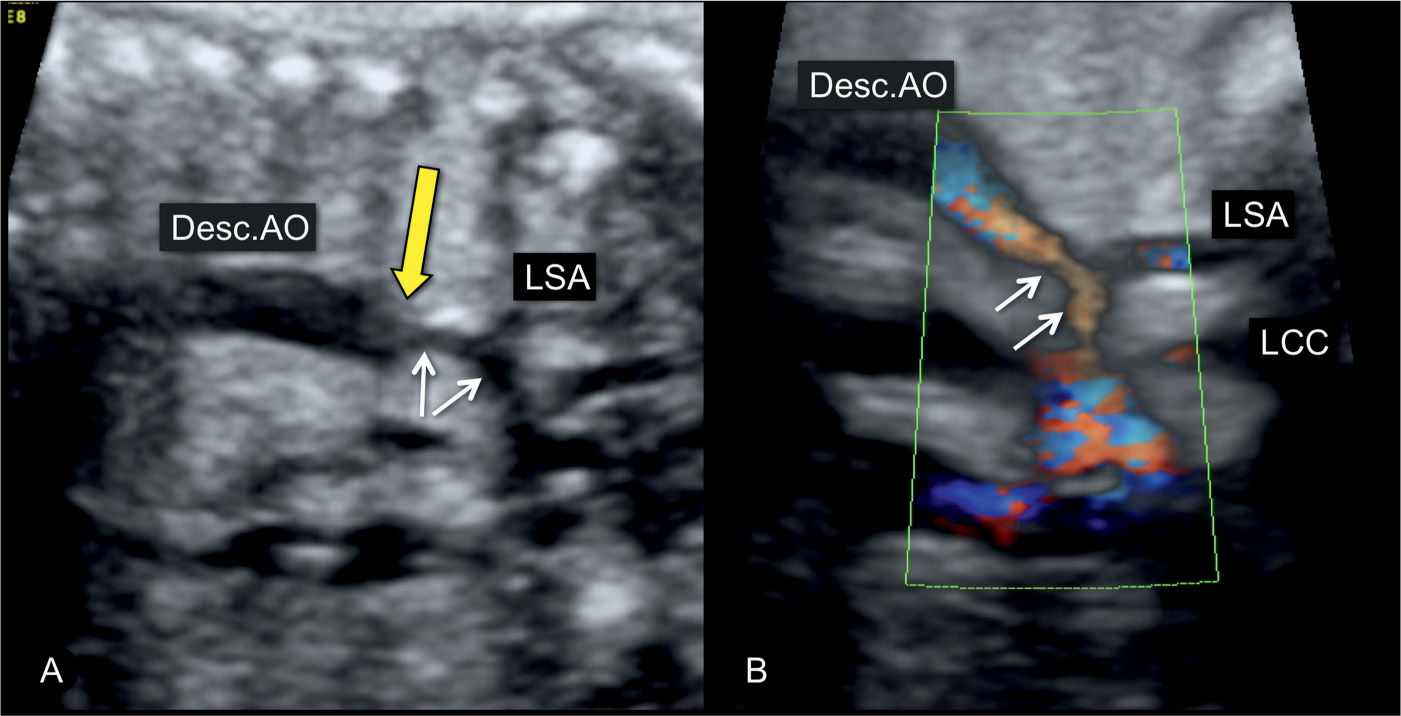

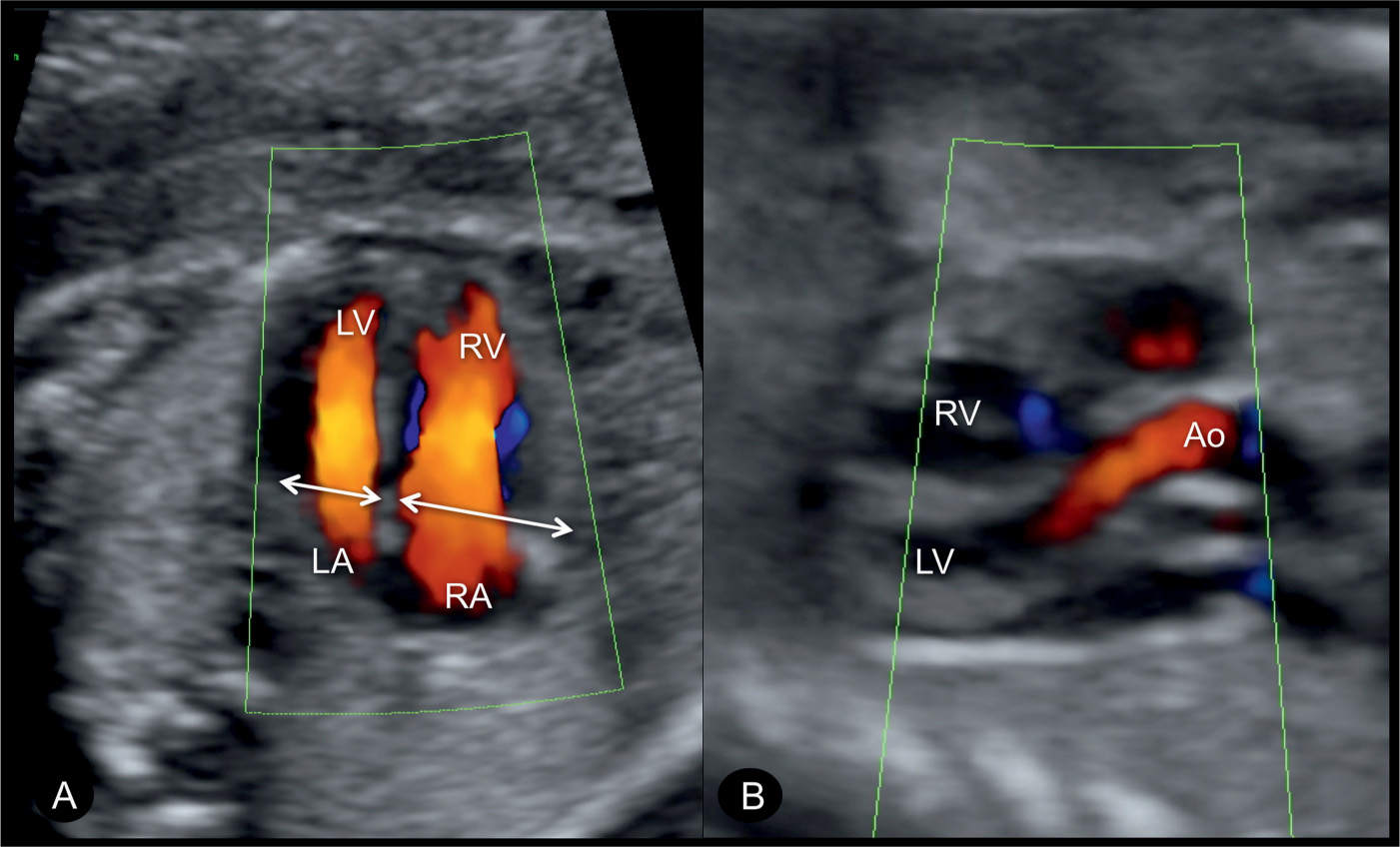

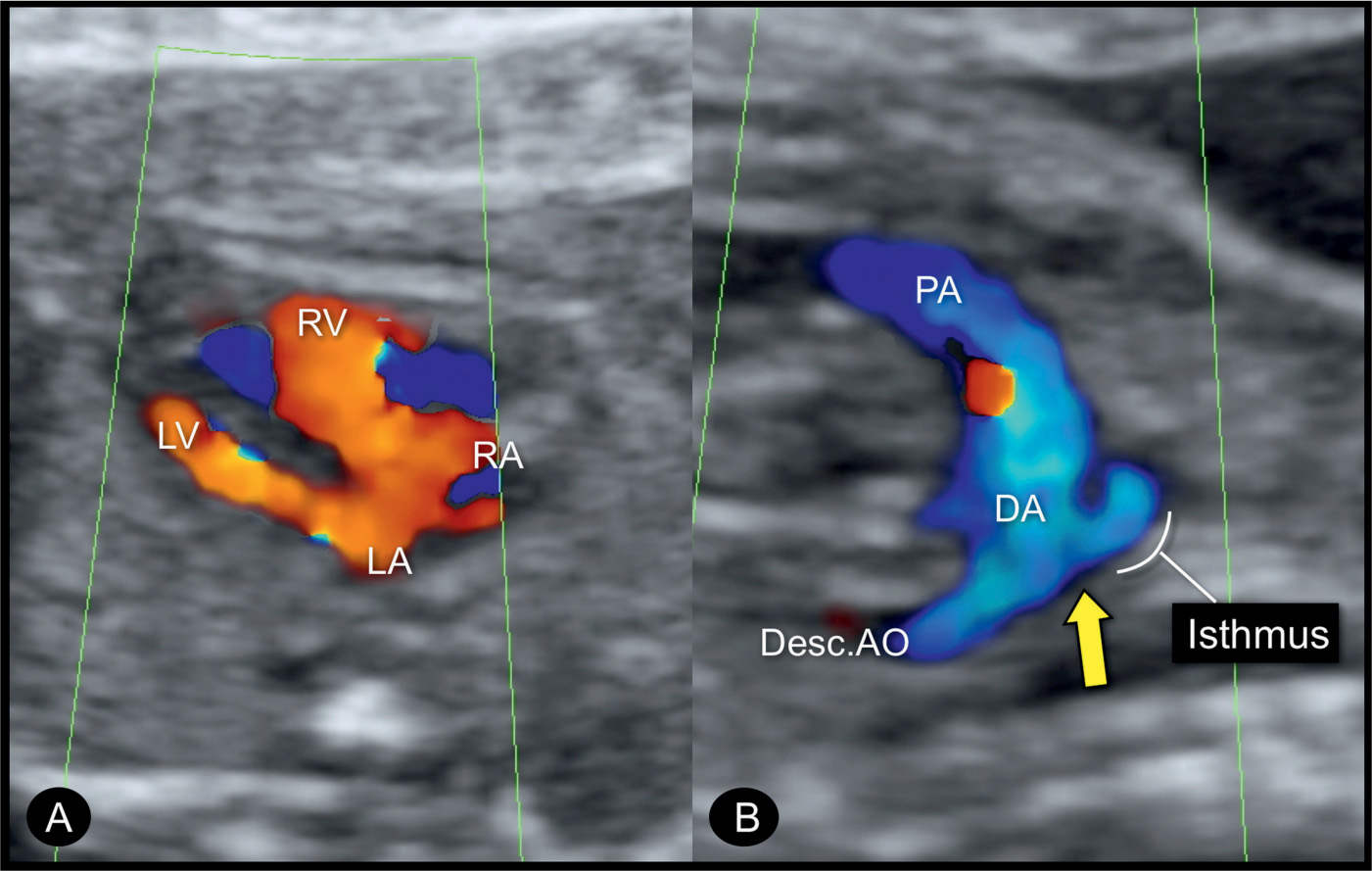

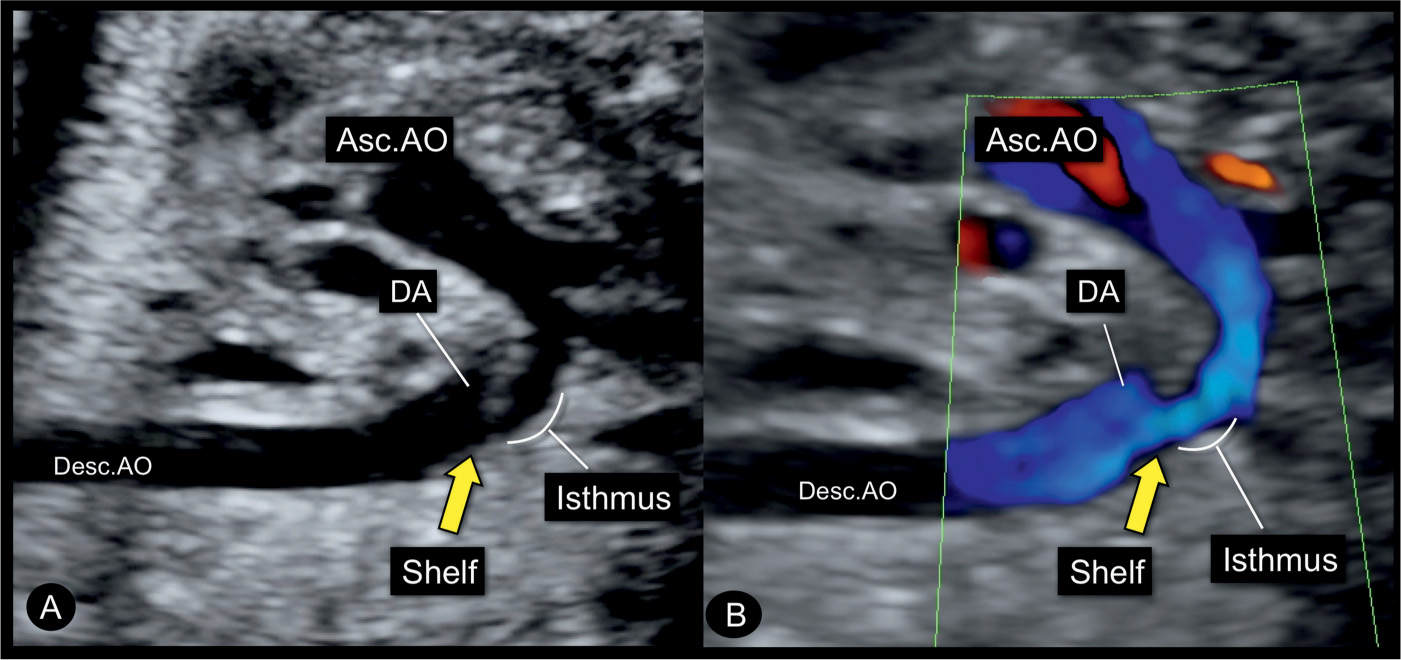

Color Doppler helps in differentiating coarctation of the aorta from other cardiac abnormalities and in demonstrating the narrow isthmic region. Applied to the four-chamber view, color Doppler confirms normal left ventricular filling in diastole and thus differentiates aortic coarctation from hypoplastic left heart syndrome (Figs. 23.9 and 23.10) (see Table 22.1 in Chapter 22). At the level of the five-chamber view, color Doppler demonstrates forward flow across the aortic valve (Fig. 23.9) and a perimembranous VSD when present, in association with coarctation of the aorta. Often the ascending aorta appears narrow at its root. In the three-vessel-trachea view or the transverse aortic arch view, a narrow transverse aortic arch can be recognized, which progressively becomes smaller in diameter as it approaches the aortic isthmus (Fig. 23.11). Despite the narrowing in the isthmic region, typically the blood flow velocities are not increased and color Doppler aliasing is not present in prenatal cases. When the aortic arch is visualized in a longitudinal plane, the use of power Doppler is preferred for a better demonstration of the aortic coarctation (Fig. 23.12). Care should be given to recognize the typical “shelf sign,” which is seen at the junction between the ductus arteriosus and the descending aorta (Figs. 23.8, 23.10, and 23.13), as this finding makes the diagnosis of aortic coarctation most likely.

Figure 23.9: Color Doppler at the level of the four-chamber (A) and five-chamber (B) views in a fetus with coarctation of the aorta. Note in A, the narrow width of the left ventricle in comparison to that of the right ventricle (double arrows) and the filling of both the left (LV) and right (RV) ventricles during diastole confirming patency of the atrioventricular valves. In the five-chamber view (B), the ascending aorta (Ao) is visualized in normal size and normal antegrade flow. LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

Figure 23.10: Color Doppler at the level of the four-chamber view (A) and sagittal aortic arch view (B) in a fetus with coarctation of the aorta. Color Doppler demonstrates the narrow width of the left ventricle (LV) and filling of the LV and the right ventricle (RV) during diastole. The sagittal arch view (B) shows the narrow aortic isthmic region and the ductus arteriosus (DA) entering the descending aorta (Desc.AO). The narrow isthmic region forms the “shelf sign” (arrow). PA, pulmonary artery; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

Figure 23.11: Color Doppler at the three-vessel-trachea view in two fetuses (A and B) with coarctation of the aorta. Fetus A is in a dorsoposterior position with blood flow into the aortic arch (AOA) and ductal arch (DA) shown in blue. Fetus B is in a dorsoanterior position with blood flow into the AOA and DA shown in red. In both fetuses, a small AOA is documented in this plane. Fetus A has a persistent left superior vena cava (LSVC). PA, pulmonary artery; SVC, superior vena cava.

Figure 23.12: Power Doppler in a sagittal view of the aortic arch in a normal fetus (A) and in a fetus with coarctation of the aorta (B). In the normal fetus (A), power Doppler displays the ascending aorta (Asc.AO), the transverse aortic arch, the aortic isthmus, and the descending aorta (Desc.AO). A also shows the three arteries that arise from the transverse arch: the brachiocephalic artery (BA), the left common carotid artery (LCC), and the left subclavian artery (LSA). In the fetus with coarctation of the aorta (B), the narrowing in the transverse aortic arch (open arrows) is shown between the left common carotid and the left subclavian artery.

Early Gestation

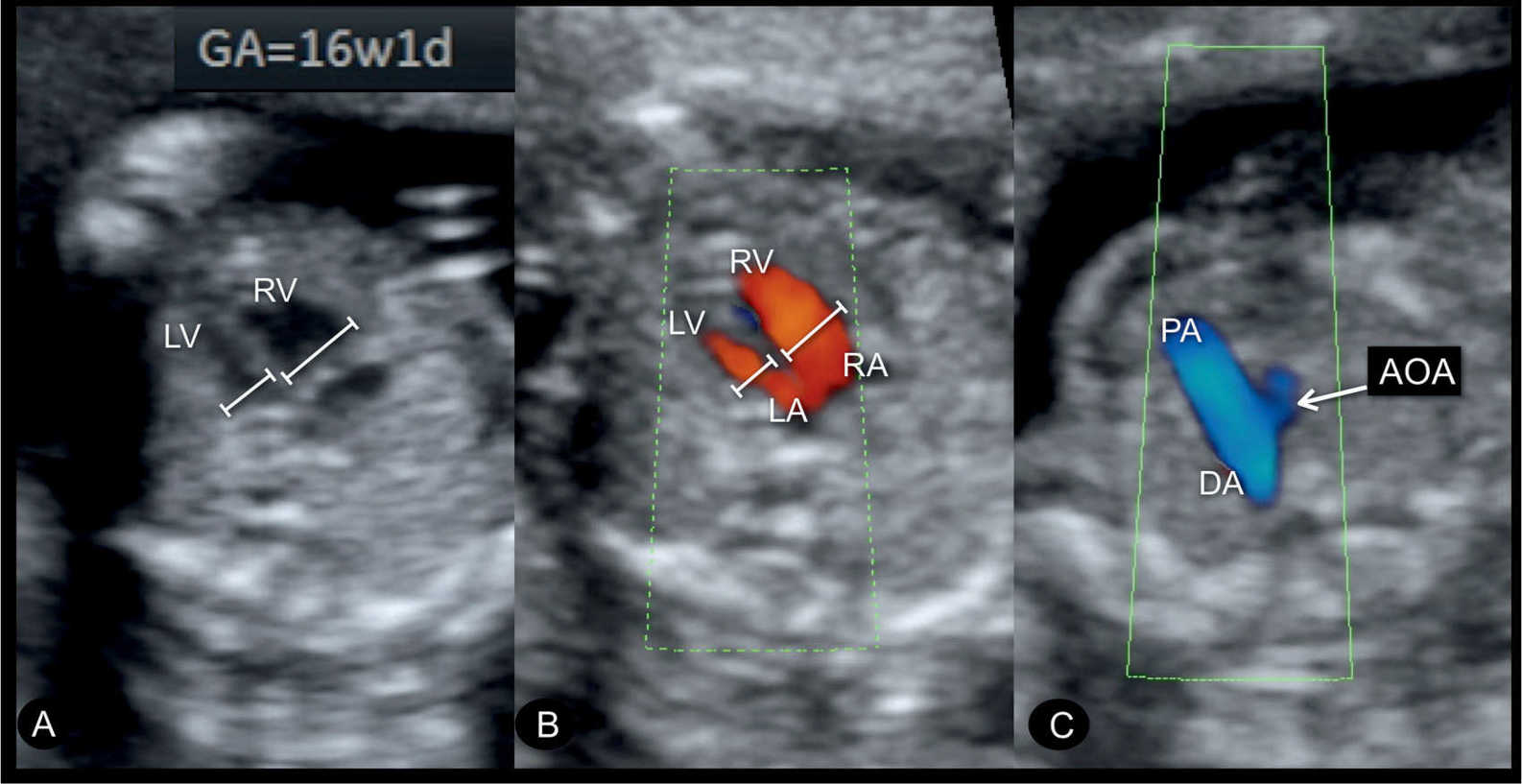

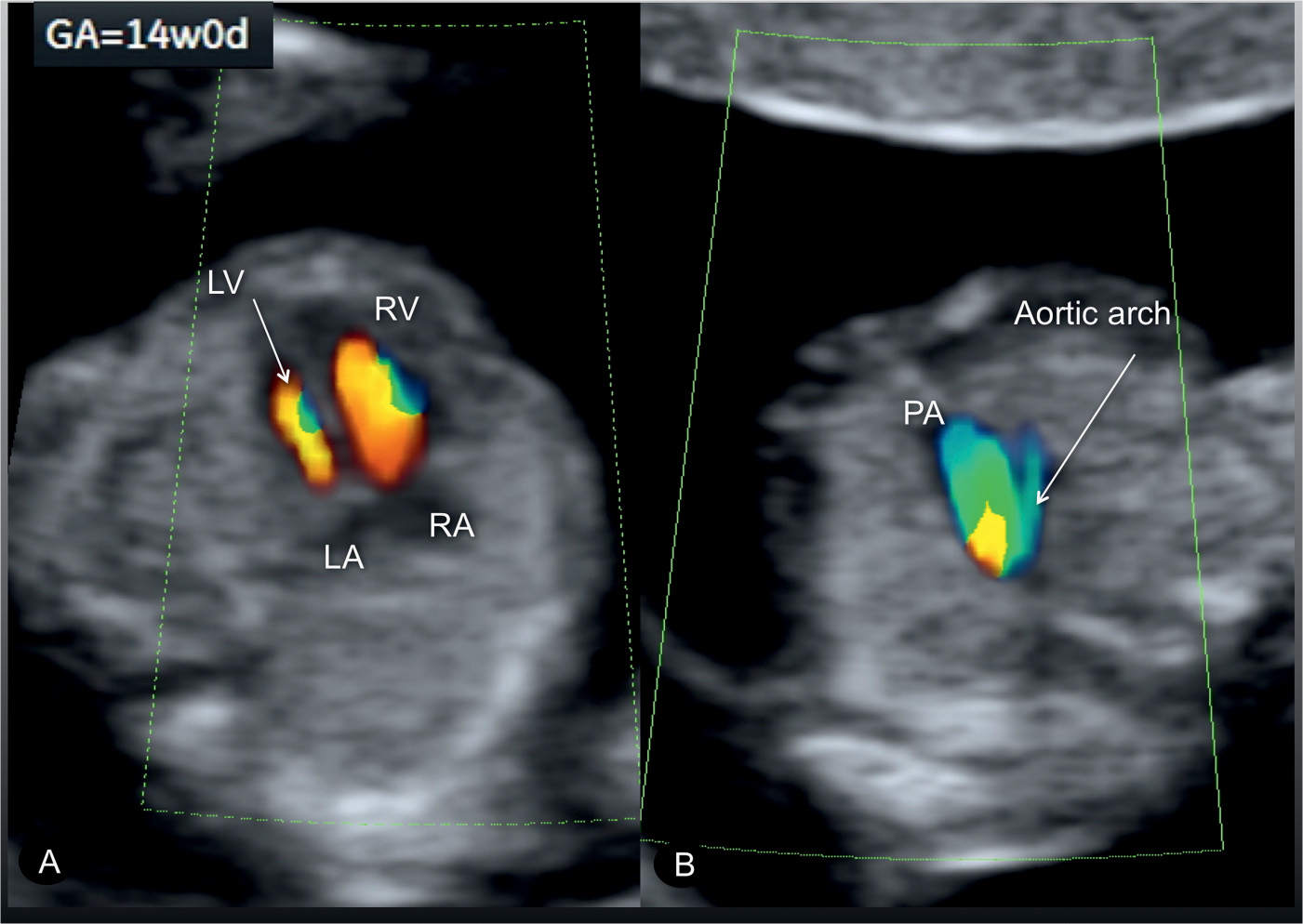

Coarctation of the aorta can be suspected in early pregnancy (Fig. 23.14) by demonstrating ventricular discrepancy as well as narrowing of the aortic arch in the three-vessel-trachea view (Fig. 23.15). Color Doppler is very helpful in early gestation in identifying the vessels in the three-vessel-trachea view (Figs. 23.14 and 23.15). The longitudinal view of the aortic arch in early gestation may support in the diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta (17). Confirming the presence of coarctation of the aorta in the second trimester is critical because ventricular discrepancies found in early pregnancy may resolve with advancing gestation. An accurate differentiation between a normal finding and a true coarctation is difficult in early gestation, making such false-positive diagnoses unavoidable. If, however, coarctation of the aorta is suspected in the presence of other findings such as cystic hygroma and/or early fetal hydrops, Turner syndrome is a likely diagnosis (18), or, when combined with impaired fetal growth and multiple structural anomalies, trisomy 13 is a likely diagnosis, since both are commonly associated with coarctation of the aorta.

Figure 23.13: Sagittal views in gray scale (A) and color Doppler (B) of the aortic arch in a fetus with coarctation of the aorta showing the narrow isthmic region. Note the typical shelf (yellow arrow) in the region of the junction of the aortic arch and the ductus arteriosus (DA) into the descending aorta (Desc.AO). Asc.AO, ascending aorta.

Figure 23.14: Gray scale (A) and color Doppler (B) at the level of the four-chamber view and the three-vessel-trachea view (C) in a fetus with coarctation of the aorta at 16 weeks’ gestation. A diminutive left ventricle (LV) is noted in the four-chamber view (A and B). Color Doppler in B shows blood filling during diastole into the LV and right ventricle (RV). A small aortic arch (AOA) is noted in the three-vessel-trachea view in C. DA, ductus arteriosus; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; PA, pulmonary artery.

Figure 23.15: Color Doppler at the level of the four-chamber view (A) and three-vessel-trachea view (B) in a fetus with coarctation of the aorta at 14 weeks’ gestation. A diminutive left ventricle (LV) is noted in the four-chamber view (A), and a small aortic arch is noted in the three-vessel-trachea view (B). RV, right ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; PA, pulmonary artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree