INTRODUCTION

The lower reproductive tract, comprising the vulva, vagina, and cervix, exhibits a wide spectrum of benign and neoplastic diseases. Disorder characteristics often overlap, and thus differentiating normal variants, benign disease, and potentially serious lesions can be challenging. Lower reproductive tract infection is a frequent cause and discussed in Chapter 3, whereas congenital anomalies and preinvasive neoplasia are infrequent and described in Chapters 18 and 29. The benign lesions highlighted in this chapter are common, and mastery of their identification and treatment is essential.

VULVAR ASSESSMENT

Vulvar skin is more permeable than surrounding tissues because of differences in structure, hydration, occlusion, and friction susceptibility (Farage, 2004). Accordingly, pathology can develop in this area, although frequency estimates are difficult because of patient underreporting and clinician misdiagnosis. Lesions may result from allergen or irritant exposure, infection, trauma, or neoplasia. As a result, symptoms may be acute or chronic and include pain, pruritus, dyspareunia, bleeding, and discharge. Effective therapies are available for most disorders, yet embarrassment and fear may prove significant roadblocks to care for many women.

The initial encounter includes reassurance that the patient’s complaints will be investigated thoroughly. Women often minimize and may be uncomfortable with describing their symptoms. They may relate protracted histories of assorted diagnoses and treatments by numerous providers and may voice frustration and doubt that relief is possible. Patients are not promised a cure but rather that every effort will be made to alleviate their symptoms. This can require multiple visits, tissue sampling, treatment attempts, and even a multidisciplinary plan. A patient-provider partnership approach to management enhances compliance and care satisfaction.

During counseling, the suspected diagnosis, current treatment plan, and recommended vulvar skin care are outlined. Printed materials that explain common conditions, medication use, and skin care are helpful. Patients are often relieved to learn that their complaints and conditions are not unique. Thus, referral to national websites and support groups is usually welcomed.

Scheduling adequate time for the initial evaluation is a wise investment, as detailed information is essential. Symptom characterization includes descriptions of abnormal sensations, duration, precise location, and associated vaginal pruritus or discharge. Patients often refer to vulvar pruritus as vaginal, and symptom location should be clarified. A thorough medical history addresses systemic illnesses, medications, and known allergies. Obstetric, sexual, and psychosocial histories and any potentially provocative events around the time of symptom onset often suggest etiologies. Hygiene and sexual practices should be investigated in detail.

Of symptoms, vulvar pruritus is frequent with many dermatoses. Patients may have been previously diagnosed with psoriasis, eczema, or dermatitis at other body sites. Isolated vulvar pruritus may be associated with a new medication. Patients may identify foods that provoke or intensify symptoms, and in such cases, a food diary may be helpful. Most often, vulvar pruritus is due to a contact or allergic dermatitis. Common offenders include strongly scented body soaps and laundry products. Excessive washing and use of wash cloths can result in skin drying and mechanical trauma. Washing often becomes more aggressive with pruritus as patients assume their hygiene is lacking. Any of these practices can create an escalating itch-scratch cycle or exacerbate the symptoms of other preexisting dermatoses. Last, patients frequently use nonprescription remedies for relief of vulvovaginal itching or perceived odor. These products commonly contain multiple known contact allergens, and their use is discouraged (Table 4-1).

| General Categories | Examples of Specific Agents |

| Antiseptics | Povidone iodine, hexachlorophene |

| Body fluids | Semen, feces, urine, saliva |

| Colored or scented toilet paper | |

| Condoms | Latex, lubricant, spermicide, thiuram |

| Contraceptive creams, jellies, foams | Nonoxynol-9, lubricants |

| Dyes | 4-Phenylene diamine |

| Emollients | Lanolin, jojoba oil, glycerin |

| Laundry detergents, fabric softeners, dryer sheets | |

| Rubber products | Latex, thiuram |

| Sanitary baby or adult bathroom wipes | |

| Sanitary pads or tampons | |

| Soaps, bubble bath and salts, shampoos | |

| Topical anesthetics | Benzocaine, lidocaine |

| Topical antibacterials | Neomycin, bacitracin, polymyxin, framycetin, tea tree oil |

| Topical corticosteroids | Clobetasol propionate |

| Topical antifungal creams | Ethylene diamine, sodium metabisulfite |

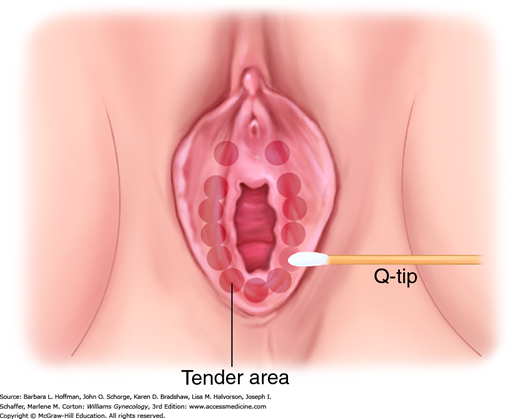

Examination of the vulva and surrounding skin is completed using adequate lighting, optimal patient positioning, and a magnifying lens or colposcope. Both focal and generalized skin changes are carefully noted, as neoplasia may arise within a field of generalized dermatosis. Abnormal pigmentation, skin texture, nodularity, or vascularity is evaluated. Touch with a small probe such as a cotton swab defines the anatomic boundaries of generalized symptoms and precisely locates focal complaints (Fig. 4-1). A medical record diagram noting vulvar findings and symptoms aids treatment assessment over time.

Vaginal complaints or vulvar conditions without obvious etiology typically prompt vaginal examination. Careful inspection may reveal generalized inflammation or atrophy, abnormal discharge, or focal mucosal lesions such as ulcers. In these cases, saline preparation of secretions for microscopic evaluation (“wet prep”), vaginal pH testing, and aerobic culture to detect yeast overgrowth are collected. A general skin examination, including the oral mucosa and axillae, may suggest the cause of some vulvar conditions. A focused neurologic examination to evaluate lower extremity sensation and strength as well as perineal sensation and tone may help evaluate vulvar dysesthesias.

Vulvar skin changes are frequently nonspecific and typically require biopsy for accurate diagnosis. Biopsy is strongly considered if the cause of symptoms is not obvious; if initial empiric treatment fails; if the cause of symptoms is not obvious; or if focal, exophytic, or hyper-/hypopigmented lesions are present. During biopsy, ulcerative lesions are sampled at their edges, and hyper- or hypopigmented areas at their thickest region (Mirowski, 2004). Conditions with variable histologic appearance may require multiple biopsies for correct disorder classification.

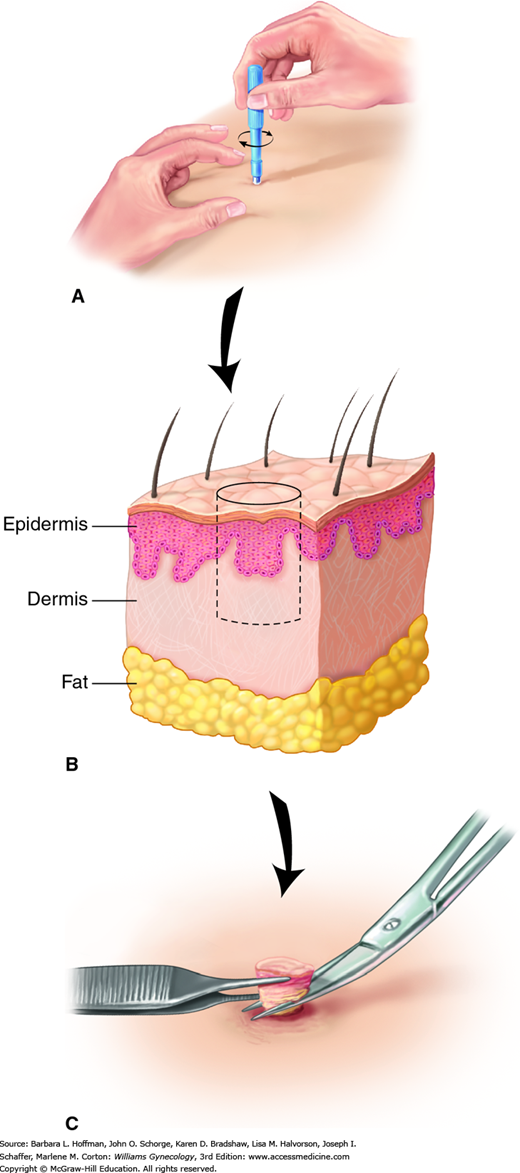

The steps for vulvar biopsy are shown in Figure 4-2. First, the biopsy site is cleaned with an antimicrobial agent and infiltrated with a 1- or 2-percent lidocaine solution. Biopsy is performed most easily with a Keyes skin punch. The open, circular blade is designed to remove a shallow disc of tissue when gently pressed against the skin and rotated. Keyes punches are available in various diameters, ranging from 2 to 6 mm, and size selection is based on lesion dimensions and on whether sampling or excision is the goal. Vulvar skin and lesion thicknesses are variable, and over-rotation of or undue pressure on the Keyes punch is avoided. Too deep a biopsy will leave a depressed scar. Rotation and pressure should stop when decreased resistance is felt, signaling the dermis has been reached. The tissue disc core is then freed at its base with fine scissors. Larger punch biopsies (4 to 6 mm) may require closure with an absorbable suture.

FIGURE 4-2

Vulvar biopsy steps. A. A Keyes punch biopsy is placed against the biopsy site. Gentle downward pressure is exerted as the punch is rotated. B. A core biopsy is created that extends through the epidermis and into the dermis. C. The tip of a fine needle or fine forceps is used to elevate the core, while fine scissors incise its base.

For raised or pedunculated lesions, fine scissors may be used. Occasionally, a No. 15 blade scalpel is selected for larger focal lesions. Tissue is excised parallel to the natural vulvar skin folds, and the defect is sutured to aid healing and minimize scarring. Larger lesions, for which simple closure would create significant incision tension, are best excised by clinicians experienced in more advanced plastic surgery techniques.

Following biopsy, bleeding may be controlled with direct pressure, silver nitrate stick, or Monsel paste. Silver nitrate may permanently discolor the skin, which may upset the patient and confuse subsequent examinations. If needed, simple interrupted stitches using a fine, rapidly absorbable suture provide hemostasis and edge approximation. Nonnarcotic oral analgesics usually suffice to relieve postbiopsy discomfort.

VULVAR DERMATOSES

The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) provides classification systems for vulvar abnormalities. Their 2006 Classification of Vulvar Dermatoses specifically focuses on dermatoses and divides these based on biopsy-obtained histology. Their more recent terminology and organization system does not supplant the 2006 system. Instead, it classifies a broader group of dermatologic disorders that includes dermatoses, infections, and neoplasias by their similar clinical presentations to aid identification and management (Lynch, 2007, 2012). The next sections describe the more frequently encountered conditions.

An itch-scratch cycle typically leads to chronic trauma from rubbing and scratching (Lynch, 2004). Early examination reveals excoriations within a background of erythema. With chronic trauma, the skin responds by thickening, termed lichenification. Thus, in long-standing cases, vulvar skin is thick with exaggerated skin markings causing a leathery, gray appearance. Skin changes are usually bilateral and symmetric and may extend beyond the labia majora. Intense vulvar pruritus causes functional and psychologic distress, and sleep is often disrupted. Potential pruritus triggers include irritation from clothing, heat, or sweating; chemicals contained within hygiene products and topical medications; laundry products; and even food sensitivities (Virgili, 2003). A detailed history typically leads to the diagnosis.

Treatment involves halting the itch-scratch cycle. First, provocative stimuli are eliminated, and topical corticosteroid ointments help to reduce inflammation. In addition, lubricants, such as plain petrolatum or vegetable oil, and cool sitz baths help to restore the skin’s barrier function. Oral antihistamine use, trimmed fingernails, and cotton gloves worn at night can help decrease scratching during sleep. If symptoms fail to resolve within 1 to 3 weeks, biopsy is indicated to exclude other pathology. Histology classically shows thickening of both the epidermis (acanthosis) and the stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis). In these refractory cases, a trial of higher-potency corticosteroid may improve symptoms.

This classically presents in postmenopausal women, although cases are less often found in premenopausal women, children, and men (Fig. 14-8). In a referral dermatologic clinic, lichen sclerosus was found in 1:300 to 1:1000 patients with a tendency toward whites (Wallace, 1971). Others estimate an incidence of childhood lichen sclerosus to be 1 in 900 (Powell, 2001).

The cause of lichen sclerosus remains unknown, although infectious, hormonal, genetic, and autoimmune etiologies have been suggested. Approximately 20 to 30 percent of patients with lichen sclerosus have other autoimmune disorders, such as Graves disease, types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, and achlorhydria, with or without pernicious anemia (Bor, 1969; Kahana, 1985; Poskitt, 1993). Accordingly, concurrent testing for these is indicated if other suggestive findings are present.

Although sometimes asymptomatic, most individuals with lichen sclerosus complain of anogenital symptoms that often worsen at night. Inflammation of local terminal nerve fibers is suspected. Pruritus-induced scratching creates a vicious cycle that may lead to excoriations and vulvar skin thickening. Late symptoms can include burning and dyspareunia due to vulvar skin fragility and structural changes.

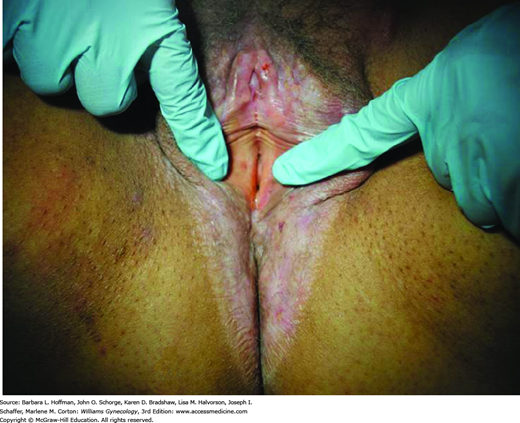

Perianal involvement is frequently seen. The typical white, atrophic papules may coalesce into porcelain-white plaques that distort normal vulvar anatomy. As a result, labia minora regression, clitoral concealment, urethral obstruction, and introital stenosis can develop. The skin generally appears thinned and crinkled. Over time, involvement may extend to the perineum and anus to form a “figure-eight” or “hourglass” shape (Fig. 4-3) (Clark, 1967). Thickened white plaques, areas of erythema, or nodularity should prompt biopsy to exclude preinvasive and malignant lesions. This characteristic clinical picture and histologic findings typically confirm the diagnosis. In long-standing cases, histologic findings may be nonspecific, and clinical suspicion will guide treatment.

Curative therapies are not available for lichen sclerosus. Thus, treatment goals are symptom control and prevention of anatomic distortion. Despite its classification as a nonneoplastic dermatosis, patients with lichen sclerosus demonstrate an increased risk of vulvar malignancy. Malignant transformation within lichen sclerosus develops in 5 percent of patients. Histologic cellular atypia may precede a diagnosis of invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Scurry, 1997). Accordingly, lifetime surveillance of women with lichen sclerosus every 12 months is prudent (Neill, 2010). Persistently symptomatic, new, or changing lesions should be biopsied (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2010).

As with all vulvar disorders, hygiene recommendations focus on minimizing chemical and mechanical skin irritation (Table 4-2). The chronicity of lichen sclerosus and lack of cure elicits an array of emotions. Support groups dedicated to this condition, such as that found at www.lichensclerosus.org, offer needed psychologic support.

| Avoid using gels, scented bath products, cleansing wipes, and soaps, as they may contain irritants Use aqueous creams to clean the vulva Avoid using a harsh washcloth to clean the vulva Dab the vulva gently to dry Avoid wearing tight-fitting pants Select white cotton underwear Avoid washing undergarments in scented washing detergents. Consider using a multirinse process with cold water to remove any remaining detergent Consider wearing skirts and no underwear at home and at night to avoid friction and aid drying |

First-line therapy for lichen sclerosus is an ultrapotent topical corticosteroid preparation such as 0.05-percent clobetasol propionate (Temovate) or 0.05-percent halobetasol propionate (Ultravate). Ointment formulations are preferred by some providers over creams due to their protective and less irritating properties (Table 4-3). Clobetasol propionate offers effective antiinflammatory, antipruritic, and vasoconstrictive properties. Theoretic adrenocorticosuppression and iatrogenic Cushing syndrome may be risks if it is used in large doses for extended periods.

| Steroid Class Potency | Generic Name | Brand Names (available forms) |

| Low | Alclometasone dipropionate 0.05% Betamethasone valerate 0.01% Fluocinolone acetonide 0.01% Hydrocortisone 1%, 2.5% | Aclovate (cream, oint.) Valisone (cream, lotion) Synalar (solution) Generic OTC versions 1% or 2.5% (cream, oint., lotion) |

| Intermediate | Betamethasone valerate 0.1% Desonide 0.05% Fluocinolone acetonide 0.025% Flurandrenolide 0.025%, 0.05% Fluticasone 0.005%, 0.05% Hydrocortisone butyrate 0.1% Hydrocortisone valerate 0.2% Mometasone furoate 0.1% Prednicarbate 0.1% Triamcinolone 0.025%, 0.1% | Valisone (cream, lotion, oint.) DesOwen (cream, oint., lotion) Synalar (cream, oint.) Cordran (cream, oint.) Cutivate 0.005% (oint.), 0.05% (cream) Locoid (cream, oint., solution) Westcort (cream, oint.) Elocon (cream, oint., lotion) Dermatop (cream, oint.) Aristocort, Kenalog (cream, oint., lotion) |

| High | Amcinonide 0.1% Betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% Desoximetasone 0.05%, 0.25% Diflorasone diacetate 0.05% Fluocinonide 0.05% Fluocinolone acetonide 0.2% Halcinonide 0.1% Triamcinolone 0.5% | Cyclocort (cream, oint., lotion) Diprolene, Diprosone (cream) Topicort (cream) Psorcon (cream, oint.) Lidex (cream, gel, oint.) Synalar-HP (cream) Halog (cream, oint., solution) Aristocort, Kenalog (cream, oint.) |

| Ultrapotent | Betamethasone dipropionate augmented 0.05% Clobetasol propionate 0.05% Diflorasone 0.05% Halobetasol propionate 0.05% | Diprolene (ointment, gel) Temovate (cream, gel, oint.) Psorcon (cream, oint.) Ultravate (cream, oint.) |

Treatment initiation within 2 years of symptom onset usually prevents significant scarring, but no treatment scheme is universally accepted for topical corticosteroid use. The currently recommended dosing schedule of the British Association of Dermatologists is 0.05-percent clobetasol propionate once nightly for 4 weeks, followed by alternating nights for 4 weeks, and finally tapering to twice weekly for 4 weeks (Neill, 2010). After this initial therapy, recommendations for maintenance therapy vary and range from tapering corticosteroids to “as needed” use to ongoing once- or twice-weekly applications. During initial treatment, some patients may also require oral antihistamines or topical 2-percent lidocaine jelly particularly at night to control itching.

Corticosteroids can also be injected into affected areas, a treatment offered by specialty clinics familiar with techniques and potential complications. One study of eight patients evaluated the efficacy of once-monthly intralesional infiltration of 25 to 30 mg of triamcinolone hexacetonide for a total of 3 months. Severity scores decreased in all categories including symptoms, gross appearance, and histopathologic findings (Mazdisnian, 1999).

Estrogen cream is not a primary therapy for lichen sclerosus. However, its addition is indicated for menopausal atrophy, labial fusion, and dyspareunia. Testosterone ointment has failed to show efficacy in trials and is no longer recommended (Bornstein, 1998; Sideri, 1994).

Retinoids are reserved for severe, nonresponsive cases of lichen sclerosus or for patients intolerant of ultrapotent corticosteroids. Topical tretinoin reduces hyperkeratosis, improves dysplastic changes, stimulates collagen and glycosaminoglycan synthesis, and induces local angiogenesis (Eichner, 1992; Kligman, 1986a,b; Varani, 1989). Virgili and colleagues (1995) evaluated the effects of topical 0.025-percent tretinoin (Retin-A, Renova) applied once daily, 5 days a week for 1 year. Complete remission of symptoms was seen in more than 75 percent of women. However, more than one quarter of patients experienced skin irritation, which is common with retinoids.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) have antiinflammatory and immunomodulating effects. These are indicated for moderate to severe eczema and have been evaluated for lichen sclerosus (Goldstein, 2011; Hengge, 2006). Moreover, these agents, compared with topical corticosteroids, theoretically lower the risk of skin atrophy, since collagen synthesis is unaffected (Assmann, 2003; Kunstfeld, 2003). However, from a double-blind, randomized, prospective study, Funaro and associates (2014) concluded that topical clobetasol propionate was more effective in treating vulvar lichen sclerosus than topical tacrolimus. In the face of recent Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concerns regarding its link to various cancers, clinicians should exercise caution when prescribing tacrolimus for extended periods (Food and Drug Administration, 2010).

Last, phototherapy after pretreatment using 5-aminolevulinic acid was investigated in one small series of 12 postmenopausal women with advanced lichen sclerosus. Significant reductions in patient symptoms and short-term improvement for up to 9 months were noted (Hillemanns, 1999).

Surgical intervention should be reserved for significant sequelae and not for primary treatment of uncomplicated lichen sclerosus. For introital stenosis, Rouzier and coworkers (2002) described marked improvements in dyspareunia and quality of sexual intercourse if perineoplasty was performed (Section 43-22). Vaginal dilation and corticosteroids are recommended following most surgical corrections of introital stenosis. For clitoral adhesions, surgical dissection can be used to free the hood from the glans. Reagglutination can be averted using initial nightly application of ultrapotent topical corticosteroid ointment (Goldstein, 2007).

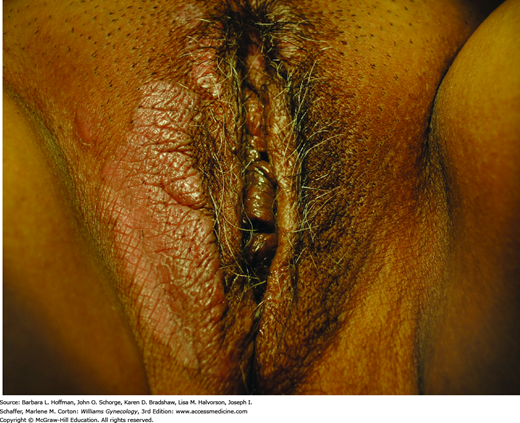

A primary irritant or allergen creates vulvar skin inflammation, termed contact dermatitis (Fig. 4-4). This condition is common, and in unexplained cases of vulvar pruritus and inflammation, irritant contact dermatitis is diagnosed in up to 54 percent of patients (Fischer, 1996).

Irritant contact dermatitis classically presents as immediate burning and stinging upon exposure to an offending agent. In contrast, patients with allergic contact dermatitis experience a delayed onset and an intermittent course of pruritus and localized erythema, edema, and vesicles or bullae (Margesson, 2004). A detailed history will help distinguish between the two, and an inquiry for potential offending agents can help identify the irritant (see Table 4-1).

With allergic contact dermatitis, patch testing may aid in identifying responsible allergen(s). Alternative conditions, such as candidiasis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and squamous cell carcinoma, can be excluded through appropriate use of cultures and biopsy.

Treatments for both entities involve elimination of the offending agent(s), restoration of the natural protective skin barrier, inflammation reduction, and scratch cessation (Table 4-4) (Farage, 2004; Margesson, 2004).

|

Friction between moist skin surfaces produces this chronic condition. Found most often in genitocrural folds, intertrigo can also develop in the inguinal and intergluteal regions. Superimposed bacterial and fungal infections may complicate the condition.

The initial erythematous phase, if untreated, can progress to intense inflammation with erosions, exudate, fissuring, maceration, and crusting (Mistiaen, 2004). Symptoms typically include burning and itching. With long-standing intertrigo, hyperpigmentation and verrucous changes can develop.

Treatment entails the use of drying agents such as cornstarch and application of mild topical corticosteroids for inflammation. If skin changes do not respond, then seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pemphigus vegetans, or even scabies are considered. If the area is superinfected with bacteria or yeast, appropriate therapy is warranted.

To prevent recurrent outbreaks, obese patients are encouraged to lose weight. Other preventions include light-weight, loose-fitting clothing made of natural fibers, improved ventilation, and thorough drying between skin folds after bathing (Janniger, 2005).

Classically presenting in the first 5 years of life, atopic dermatitis is a severe pruritic dermatitis that follows a chronic, relapsing course. Scaly patches with fissuring are evident. Individuals with atopic eczema may later develop allergic rhinitis and asthma (Spergel, 2003).

Topical corticosteroids and immunomodulators, such as tacrolimus, can control flares (Leung, 2004). For dry skin, moisturizing with emollients can offer relief.

Approximately 1 to 2 percent of the United States’ population is affected by psoriasis (Gelfand, 2005). Psoriasis is a T-cell—mediated autoimmune process in which proinflammatory cytokines induce keratinocyte and endothelial cell proliferation. Thick, red plaques covered with silvery scales are generally found on extensor limb surfaces. Occasionally, lesions involve the mons pubis or labia (Fig. 4-5). Psoriasis can be exacerbated by nervous stress and menses, with remissions experienced during summer months and pregnancy. Pruritus may be minimal or absent, and this condition is often diagnosed by skin findings alone.

Several treatments are available, and topical corticosteroids are widely used because of their rapid efficacy. High-potency corticosteroids are applied to affected areas twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks and then reduced to weekly applications. Diminishing response and skin atrophy are potential disadvantages of long-term corticosteroid use, and recalcitrant cases are best managed by a dermatologist. Vitamin D analogues, such as calcipotriene (Dovonex), although similar in efficacy to potent corticosteroids, are frequently associated with local irritation but avoid skin atrophy (Smith, 2006). Phototherapy offers short-term relief, but long-term treatment plans require a multidisciplinary team (Griffiths, 2000). For moderate to severe psoriasis, several FDA-approved immunomodulating biologic agents are available and include infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab (Smith, 2009).

This uncommon disease involves both cutaneous and mucosal surfaces and affects genders equally between ages 30 and 60 years (Mann, 1991). Although not completely understood, T-cell autoimmunity directed against basal keratinocytes is thought to underlie its pathogenesis (Goldstein, 2005). Vulvar lichen planus can present as one of three variants: (1) erosive, (2) papulosquamous, or (3) hypertrophic. Of these, erosive lichen planus is the most common vulvovaginal form and the most difficult variant to treat. Lichen planus may be drug-induced, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, β-blocking agents, methyldopa, penicillamine, and quinine drugs have been implicated.

Table 4-5 summarizes the most common imitators of lichen planus. Women typically complain of chronic vaginal discharge with intense vulvovaginal pruritus, burning pain, dyspareunia, and postcoital bleeding. On inspection, papules classically are brightly erythematous or violaceous, flat-topped, shiny polygons most commonly found on the trunk, buccal mucosa, or flexor surfaces of the extremities (Goldstein, 2005; Zellis, 1996). Lacy, white striations (Wickham striae) are frequently found in conjunction with the papules and may also be present on the buccal mucosa (Fig. 4-6). Deep, painful erosions in the posterior vestibule can extend to the labia, resulting in agglutination. With speculum insertion, vulvar skin and vaginal mucosa bleed easily. Vaginal erosions can produce adhesions and synechiae, which may lead to vaginal obliteration.

| Class of Lichen Planus | Mimicking Condition |

| Erosive lichen planus | Lichen sclerosus Pemphigoid vulgaris Mucous membrane pemphigoid Behçet disease Plasma cell vulvitis Erythema multiforme major Stephen-Johnson syndrome Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis |

| Papulosquamous lichen planus Hypertropic lichen planus | Molluscum contagiosum Genital warts Squamous cell carcinoma |

FIGURE 4-6

Oral lichen planus. Mucosal lesions manifest commonly as lacy, white striations (Wickham striae), although white papules or plaques, erosions, or blisters may also be seen. Oral lesions predominantly affect the buccal mucosa, tongue, and gingiva. (Used with permission from Dr. Edward Ellis.)

Women with suspected lichen planus require a thorough dermatologic survey looking for extragenital lesions. Nearly one quarter of women with oral lesions will have vulvovaginal involvement, and most with erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus will have oral involvement (Pelisse, 1989). Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Pharmacotherapy remains the first-line treatment for this condition. Additionally, vulvar care measures, discontinuing any medications associated with lichenoid changes, and psychologic support should be instituted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree