INTRODUCTION

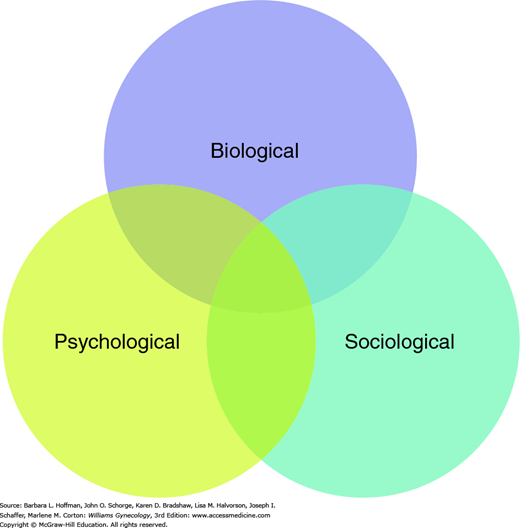

Thirty years ago, psychiatrist George Engel coined the term “biopsychosocial model” to describe a developing paradigm for patient care (Engel, 1977). As shown in Figure 13-1, the model encourages treatments that consider the mind and body of a patient as two intertwining systems influenced by a third system—society. This was perhaps the first time a distinction was drawn between “disease” and “illness.” Namely, disease is the pathological process, and illness is the patient’s experience of that process. In keeping with this model, psychological factors have two distinct relationships with women’s reproductive health. At times, they are a consequence (infertility has been linked with psychological distress). At other times, they may be an insidious cause of a health problem (increased hysterectomy rates are noted in women with a low tolerance for the physical discomfort of menstruation).

Years before Engel’s work, Erik Erikson (1963) created a model that describes psychological maturation in stages across the life span. Specifically, adolescents are confronted with identity development; reproductive-aged women with intimacy concerns; peri- and early menopausal women with productivity issues; and older women with life review. Combining Erikson’s developmental model with Engel’s psychosocial model provides a dimensional perspective to aid the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of any patient.

Not only do women use more health care services in general than men in the United States, but more women approach their physicians with psychiatric complaints, and more women have comorbid illness than men (Andrade, 2003; Kessler, 1994). Because primary care is the setting in which most patients with psychiatric illness are first seen, obstetricians and gynecologists often are the first to evaluate a woman in psychiatric distress. The clinical interview in Table 13-1 provides an example of an assessment that includes all three domains from the biopsychosocial model.

| Component | Consideration |

| Present or past psychiatric illness | Relation to reproductive triggers: pregnancy, menses, menopause, etc. |

| Medications | All medications and supplements; exogenous hormones |

| Diet | Abnormal eating patterns; diet pills, laxatives, diuretics |

| Substance use | Covert use, especially of prescription drugs |

| Family | Including their premenstrual and postpartum mood disorders |

| Medical | Autoimmune disease, which can present with psychiatric symptoms |

| Menstrual | Premenstrual or perimenopausal symptoms |

| Social | Current or past sexual, physical, or emotional abuse. Note sexual preference and current relationship satisfaction |

| Economic | Ability to meet ongoing financial needs |

MOOD DISORDERS

Mood, anxiety, and alcohol or substance use disorders are three families of psychiatric disorders commonly seen and often comorbid with reproductive problems. These three groups are defined by specific criteria described by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Each family of disorders is characterized by predominant features, and each disorder within those families is identified by specific symptoms of that feature.

Of these families, mood disorders are categorized as depressive disorders (major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, other specified depressive disorder, and unspecified depressive disorder) or as bipolar and related disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, cyclothymic disorder, other specified bipolar disorder, and unspecified bipolar disorder). For bipolar disorders, defining behaviors include racing thoughts, inflated grandiosity, psychomotor agitation, loquaciousness, and high-risk behavior, among others. These are severe enough to impair occupational or social relationships.

For depressive disorders, symptoms include those in Table 13-2. The lifetime prevalence in the general U.S. population approximates 20 percent (Kessler, 2005). As such, depression is a major cause of disability, and females are l.6 times more likely than men to suffer from a major depressive episode (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). Women also may experience one or more comorbid psychiatric disorders, most commonly an anxiety disorder and/or substance use disorder.

| A. | 5 criteria present during the same 2-week period and represent change from previous functioning. At least one of these is: |

| Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day | |

| Markedly diminished interest/pleasure in most activities, most of the day, most days | |

| The balance of 5 from these: | |

| Significant weight loss/gain, change in appetite, or failure to make expected gains | |

| Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day | |

| Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day, observable by others | |

| Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day | |

| Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day | |

| Diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness | |

| Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation, plans, or attempt | |

| B. | Symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in functioning |

| C. | Symptoms are not due to a substance or a general medical condition |

| D. | Symptoms not accounted by other psychiatric disorder |

| E. | No prior mania or hypomania |

Self-report questionnaires are generally used to identify individuals who require further psychiatric evaluation (screening measures) and may also assess the frequency and intensity of depressive symptoms (severity measures). The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR) is one such tool easily implemented for clinical use (Tables 13-3 and 13-4) (Rush, 2003). Further information regarding the instrument is available at www.ids-qids.org. By patient report, this questionnaire assesses symptom severity required by DSM-5 criteria to diagnosis major depressive disorder. Ultimately, diagnosing mood disorders requires assessment by a trained clinician.

| CHECK THE ONE RESPONSE TO EACH ITEM THAT BEST DESCRIBES YOU FOR THE PAST SEVEN DAYS. | ||

| During the past seven days | ||

| 1. | Falling Asleep: | |

| □ | 0 | I never take longer than 30 minutes to fall asleep. |

| □ | 1 | I take at least 30 minutes to fall asleep, less than half the time. |

| □ | 2 | I take at least 30 minutes to fall asleep, more than half the time. |

| □ | 3 | I take more than 60 minutes to fall asleep, more than half the time. |

| 2. | Sleep During the Night: | |

| □ | 0 | I do not wake up at night. |

| □ | 1 | I have a restless, light sleep with a few brief awakenings each night. |

| □ | 2 | I wake up at least once a night, but I go back to sleep easily. |

| □ | 3 | I awaken more than once a night and stay awake for 20 minutes or more, more than half the time. |

| 3. | Waking Up Too Early: | |

| □ | 0 | Most of the time, I awaken no more than 30 minutes before I need to get up. |

| □ | 1 | More than half the time, I awaken more than 30 minutes before I need to get up. |

| □ | 2 | I almost always awaken at least one hour or so before I need to, but I go back to sleep eventually. |

| □ | 3 | I awaken at least one hour before I need to, and can’t go back to sleep. |

| 4. | Sleeping Too Much: | |

| □ | 0 | I sleep no longer than 7–8 hours/night, without napping during the day. |

| □ | 1 | I sleep no longer than 10 hours in a 24-hour period including naps. |

| □ | 2 | I sleep no longer than 12 hours in a 24-hour period including naps. |

| □ | 3 | I sleep longer than 12 hours in a 24-hour period including naps. |

| 5. | Feeling Sad: | |

| □ | 0 | I do not feel sad. |

| □ | 1 | I feel sad less than half the time. |

| □ | 2 | I feel sad more than half the time. |

| □ | 3 | I feel sad nearly all of the time. |

| Please complete either 6 or 7 (not both) | ||

| 6. | Decreased Appetite: | |

| □ | 0 | There is no change in my usual appetite. |

| □ | 1 | I eat somewhat less often or lesser amounts of food than usual. |

| □ | 2 | I eat much less than usual and only with personal effort. |

| □ | 3 | I rarely eat within a 24-hour period, and only with extreme personal effort or when others persuade me to eat. |

| -OR- | ||

| 7. | Increased Appetite: | |

| □ | 0 | There is no change from my usual appetite. |

| □ | 1 | I feel a need to eat more frequently than usual. |

| □ | 2 | I regularly eat more often and/or greater amounts of food than usual. |

| □ | 3 | I feel driven to overeat both at mealtime and between meals. |

| Please complete either 8 or 9 (not both) | ||

| 8. | Decreased Weight (Within the Last Two Weeks): | |

| □ | 0 | I have not had a change in my weight. |

| □ | 1 | I feel as if I have had a slight weight loss. |

| □ | 2 | I have lost 2 pounds or more. |

| □ | 3 | I have lost 5 pounds or more. |

| -OR- | ||

| 9. | Increased Weight (Within the Last Two Weeks): | |

| □ | 0 | I have not had a change in my weight. |

| □ | 1 | I feel as if I have had a slight weight gain. |

| □ | 2 | I have gained 2 pounds or more. |

| □ | 3 | I have gained 5 pounds or more. |

| During the past seven days… | ||

| 10. | Concentration/Decision-Making: | |

| □ | 0 | There is no change in my usual capacity to concentrate or make decisions. |

| □ | 1 | I occasionally feel indecisive or find that my attention wanders. |

| □ | 2 | Most of the time, I struggle to focus my attention or to make decisions. |

| □ | 3 | I cannot concentrate well enough to read or cannot make even minor decisions. |

| 11. | View of Myself: | |

| □ | 0 | I see myself as equally worthwhile and deserving as other people. |

| □ | 1 | I am more self-blaming than usual. |

| □ | 2 | I largely believe that I cause problems for others. |

| □ | 3 | I think almost constantly about major and minor defects in myself. |

| 12. | Thoughts of Death or Suicide: | |

| □ | 0 | I do not think of suicide or death. |

| □ | 1 | I feel that life is empty or wonder if it’s worth living. |

| □ | 2 | I think of suicide or death several times a week for several minutes. |

| □ | 3 | I think of suicide or death several times a day in some detail, or I have made specific plans for suicide or have actually tried to take my life. |

| 13. | General Interest: | |

| □ | 0 | There is no change from usual in how interested I am in other people or activities. |

| □ | 1 | I notice that I am less interested in people or activities. |

| □ | 2 | I find I have interest in only one or two of my formerly pursued activities. |

| □ | 3 | I have virtually no interest in formerly pursued activities. |

| During the past seven days… | ||

| 14. | Energy Level: | |

| □ | 0 | There is no change in my usual level of energy. |

| □ | 1 | I get tired more easily than usual. |

| □ | 2 | I have to make a big effort to start or finish my usual daily activities (for example, shopping, homework, cooking, or going to work). |

| □ | 3 | I really cannot carry out most of my usual daily activities because I just don’t have the energy. |

| 15. | Feeling Slowed Down: | |

| □ | 0 | I think, speak, and move at my usual rate of speed. |

| □ | 1 | I find that my thinking is slowed down or my voice sounds dull or flat. |

| □ | 2 | It takes me several seconds to respond to most questions, and I’m sure my thinking is slowed. |

| □ | 3 | I am often unable to respond to questions without extreme effort. |

| During the past seven days… | ||

| 16. | Feeling Restless: | |

| □ | 0 | I do not feel restless. |

| □ | 1 | I’m often fidgety, wringing my hands, or need to shift how I am sitting. |

| □ | 2 | I have impulses to move about and I am quite restless. |

| □ | 3 | At times, I am unable to stay seated and need to pace around. |

|

ANXIETY DISORDERS

Anxiety disorders have the highest prevalence rates in the United States. Lifetime rates approximate 30 percent, and similar to depression, women are 1.6 times more likely to be diagnosed than men (Kessler, 2005). Criteria established in the DSM-5 provide guidelines to help distinguish anxiety disorders from normally expected worries (Table 13-5).

| A. | Excessive anxiety and worry about a number of events or activities. This occurs more days than not for at least 6 months | |

| B. | The person finds it difficult to control the worry | |

| C. | The anxiety and worry are associated with ≥3 of the following six symptoms: | |

| Easily fatigued | Irritability | |

| Muscle tension | Disturbed sleep | |

| Difficulty concentrating | Restless or keyed up | |

| D. | The anxiety, worry, or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning | |

| E. | The disturbance is not due to physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition | |

| F. | Symptoms not better explained by another mental disorder | |

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

In the United States, the lifetime prevalence for alcohol and substance use disorders approximates 15 percent. This diagnosis is twice as likely in males, although rates in women are increasing (Kessler, 2005). Indicators of substance misuse are found in Table 13-6. Often substance abuse disorders coexist with mood and anxiety disorders. A detailed discussion of these issues is beyond this chapter’s scope, but additional information regarding alcohol and other commonly abused substances, including prescription medications, is found at: http://www.drugabuse.gov.

A maladaptive pattern of substance use, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by two or more of the following, occurring at any time in the same 12-month period:

|

EATING DISORDERS

Specific feeding and eating disorders classified by the DSM-5 and relevant to women’s health care are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and unspecified feeding or eating disorder (Tables 13-7 and 13-8). The core symptoms of both anorexia and bulimia are preoccupation with weight gain and excessive self-evaluation of weight and body shape, accompanied by either restriction of food intake (anorexia) or the use of compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain after binge eating (bulimia). Binge-eating disorder is differentiated by consuming larger amounts of food, lacking a sense of control over the eating, but not engaging in subsequent weight-loss behaviors. These disorders are 10 to 20 times more common in females than in males, particularly in those aged 15 to 24 years (Mitchell, 2006). In young females, an estimated 4 percent suffer from anorexia, 1 to 1.5 percent from bulimia, and 1.6 percent from binge-eating disorder. While anorexia usually begins early in adolescence and peaks around age 17, bulimia nervosa typically has a later onset than anorexia and is more prevalent over the life span (Hoek, 2006). Pathological eating is also found in older women, particularly binge-eating disorder and unspecified eating disorder (Mangweth-Matzek, 2014).

| A. | Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimal normal weight for age and height |

| B. | Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight |

| C. | Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low weight |

| Restricting Type: No binge-eating or purging behaviors | |

| Binge-Eating/Purging Type: Binge-eating and self-induced vomiting, or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas | |

| A. | Recurrent episodes of binge eating |

| Eating, in a discrete period of time, an amount of food definitely larger than most people would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances | |

| A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode | |

| B. | Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise |

| C. | Binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least once a week for 3 months |

| D. | Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight |

| E. | The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa |

The exact etiology of such abnormal consumption is unknown. However, evidence suggests a strong familial aggregation for eating disorders (Stein, 1999). In the restricting type of anorexia, the concordance rate among monozygotic twins approximates 66 percent and 10 percent for dizygotic twins (Treasure, 1989). Various biologic factors have been implicated in eating disorder development. Abnormalities in neuropeptides, neurotransmitters, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes are reported (Stoving, 2001). In addition, psychological and psychodynamic factors related to an absence of autonomy are thought to influence obsessive preoccupations. Although eating disorders are believed to be a Western culture phenomenon, rates are also increasing in non-Western cultures (Lai, 2013).

Anorexia nervosa is divided into two subtypes: (1) a restricting type and (2) a binge-eating/purging type, which is distinguished from bulimia by weighing less than the minimum standard for normal. Symptoms begin as unique eating habits that become more and more restrictive. Advanced symptoms may include extreme food intake restriction and excessive exercise. Up to 50 percent of anorectics also show bulimic behavior, and these types may alternate during the course of anorexic illness. Bulimic-type anorectics have been found to engage in two distinct behavior patterns, those who binge and purge and those who solely purge. The body-mass index percentile, clinical symptoms, degree of disability, and need for supervision determine clinical severity.

Diagnosis of anorexia is initially challenging as patients often defend their eating behaviors upon confrontation and rarely recognize their illness. They increasingly isolate themselves socially as their disorder progresses. Multiple somatic complaints such as gastrointestinal symptoms and cold intolerance are common. In the disorder’s later stages, weight loss becomes more apparent, and medical complications may prompt patients to seek help. Findings often include dental problems, general nutritional deficiency, electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia and alkalosis), and decreased thyroid function. Electrocardiogram changes such as QT prolongation (bradycardia) and inversion or flattened T-waves may be noted. Rare complications include gastric dilatation, arrhythmias, seizure, and death.

Bulimia nervosa is identified by periods of uncontrolled eating of high-calorie foods (binges), followed by compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, fasting, excessive exercise, or misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or emetics. Unlike patients with anorexia, those with bulimia often recognize their maladaptive behaviors. Severity is based on the frequency of the inappropriate behaviors, clinical symptoms, and level of disability. Most bulimics have normal weights, although their weight may fluctuate. Physical changes may be subtle and include dental problems, swollen salivary glands, or knuckle calluses on the dominant hand. Termed Russell sign, calluses form in response to repetitive contact with stomach acid during purging (Strumia, 2005).

Binge-eating disorder is distinct from anorexia and bulimia. It is characterized by ingesting large amounts of food within a short time and is accompanied by feelings that one cannot control the amount of food eaten. Severity is assessed according to the number of gorging episodes per week. Binge-eating is associated with obesity. That said, most obese individuals do not necessarily engage in binge episodes and consume comparatively fewer calories than those with the syndrome. Prevalence in the United States approximates 1.6 percent for females and 0.8 percent for males, and in middle-aged women, binge-eating is more common than anorexia or bulimia (Mangweth-Matzek, 2014).

All these are complex disorders that affect both psychological and physical systems and are often comorbid with depression and anxiety. Rates of mood symptoms approximate 50 percent, and anxiety symptoms, 60 percent (Braun, 1994). Simple phobia and obsessive-compulsive behaviors may also coexist. In many cases, patients with anorexia have rigid, perfectionistic personalities and low sexual interest. Patients with bulimia often display sexual conflicts, problems with intimacy, and impulsive suicidal tendencies.

A multidisciplinary approach benefits the treatment of eating disorders. Practice approaches include: (1) nutritional rehabilitation, (2) psychosocial treatment that includes individual and family therapies, and (3) pharmacotherapeutic treatment of concurrent psychiatric symptoms. Online resources for information and support are provided by the National Eating Disorder Association, www.edap.org and Academy for Eating Disorders, www.aedweb.org. However, health care providers should also be aware of eating disorder advocacy websites (Norris, 2006).

Data concerning the long-term physical and psychological prognosis of women with eating disorders are limited. Most may symptomatically improve with aging. However, complete recovery from anorexia nervosa is rare, and many continue to have distorted body perceptions and peculiar eating habits. Overall, the prognosis for bulimia is better than for anorexia.

MENSTRUATION-RELATED DISORDERS

Frequently, reproductive-aged women experience symptoms during the late luteal phase of their menstrual cycle. Collectively these complaints are termed premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or, when more severe and disabling, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Nearly 300 different symptoms have been reported and typically include both psychiatric and physical complaints. For most women, these are self-limited. However, approximately 15 percent report moderate to severe complaints that cause some impairment or require special consideration (Wittchen, 2002). Current estimates are that 3 to 8 percent of menstruating women meet the strict criteria for PMDD (Halbreich, 2003b).

The exact causes of these disorders are unknown, although several different biological factors have been suggested. Of these, estrogen and progesterone, as well as the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonin, are frequently studied.

First, estrogen and progesterone are integral to the menstrual cycle. The cyclic complaints of PMS begin following ovulation and resolve with menses. PMS is less common in women with surgical oophorectomy or drug-induced ovarian hypofunction, such as with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (Cronje, 2004; Wyatt, 2004). Moreover, women with anovulatory cycles appear protected. One potential effect stems from estrogen and progesterone’s influence on central nervous system neurotransmitters: serotonin, noradrenaline, and GABA. The predominant action of estrogen is neuronal excitability, whereas progestins are inhibitory (Halbreich, 2003a). Menstruation-related symptoms are believed to be associated with neuroactive progesterone metabolites. Of these, allopregnanolone is a potent modulator of GABA receptors, and its effects mirror those of low-dose benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and alcohol. These effects may include loss of impulse control, negative mood, and aggression or irritability (Bäckström, 2014). Wang and colleagues (1996) noted fluctuations in allopregnanolone across the various menstrual cycle phases. These changes were implicated with PMS symptom severity.

Second, evidence also supports a role for serotonergic system dysregulation in PMS pathophysiology. Decreased serotonergic activity has been noted in the luteal phase. Moreover, trials of serotonergic treatments show PMS symptom reduction (Majoribanks, 2013).

Last, sex steroids also interact with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) to alter electrolyte and fluid balance. The antimineralocorticoid properties of progesterone and possible estrogen activation of the RAAS system may explain PMS symptoms of bloating and weight gain.

PMDD is identified in the DSM-5 by the presence of at least five symptoms accompanied by significant psychosocial or functional impairment (Table 13-9). PMS refers to the presence of numerous symptoms that are not associated with significant impairment. During evaluation, the revised criteria in DSM-5 recommend that clinicians confirm symptoms by prospective patient mood charting for at least two menstrual cycles. In certain instances, complaints may be an exacerbation of an underlying primary psychiatric condition(s). Thus, other common psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders are excluded. Additionally, other medical conditions that have a multisystem presentation are considered. These include hypothyroidism, systemic lupus erythematosus, endometriosis, anemia, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibrocystic breast disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and migraine.

|

Therapy for PMDD and PMS include psychotropic agents, ovulation suppression, and dietary modification. Generalists may consider treatment of mild to moderate cases. However, if treatment fails or if symptoms are severe, then psychiatric referral may be indicated (Cunningham, 2009).

Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered primary therapy for psychological symptoms of PMDD and PMS, and fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine are Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for this indication (Table 13-10). Standard dosages are administered in either continuous dosing or luteal phase (14 days prior to expected menses) dosing regimens. Several well-controlled trials of SSRIs have shown these drugs to be efficacious and well tolerated (Shah, 2008). In addition, short-term use of anxiolytics such as alprazolam or buspirone offers added benefits to some women with prominent anxiety. However, in prescribing benzodiazepines, caution is taken in women with prior history of substance abuse (Nevatte, 2013).

| Drug Class | Indication | Examples a | Brand Name | Commonly Reported Side Effects |

| Selective serotonin- reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | Depressive, anxiety, and premenstrual disorders | Fluoxetine c Citalopram c Escitalopram c Sertraline c Paroxetine d Fluvoxamine c | Prozac, Sarafem Celexa Lexapro Zoloft Paxil Luvox | Nausea, headache, insomnia, diarrhea, dry mouth, sexual dysfunction |

| Serotonin noradrenergic- reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) | Depressive, anxiety, and premenstrual disorders | Venlafaxine XR c Duloxetine c Levomilnacipran c Desvenlafaxine c | Effexor Cymbalta Fetzima Pristiq | Dry mouth, anxiety, agitation, dizziness, somnolence, constipation |

| Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants | Depressive and anxiety disorders | Desipramine c Nortriptyline d Amitriptyline c Doxepin c Maprotiline b | Norpramin Pamelor, Aventyl Elavil Sinequan Ludiomil | Drowsiness, dry mouth, dizziness, blurred vision, confusion, constipation, urinary retention and frequency |

| Benzodiazepines | Anxiety disorders | Alprazolam d Clonazepam d Diazepam d | Xanax Klonopin Valium | Drowsiness, ataxia, sleep changes, impaired memory, hypotension |

| Others | Depressive disorders | Nefazodone c Trazodone c Bupropion SR, XL c | Serzone Desyrel Wellbutrin | Headache, dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, somnolence |

| Mirtazipine c | Remeron | Dry mouth, increased appetite, somnolence, constipation | ||

| Vilazodone c Aripiprazole c , e | Viibryd Abilify | Diarrhea, nausea, dry mouth Weight gain, akathisia, extrapyramidal signs, somnolence | ||

| Vertioxetine c | Brintellix | Constipation, nausea, vomiting | ||

| Anxiety disorders | Buspirone b Hydroxyzine c | Buspar Vistaril, Atarax | Dizziness, drowsiness, headache | |

| Sleep agents | Zaleplon c Zolpidem c Ramelteon c Eszopiclone c | Sonata Ambien, Intermezzo, Edluar, Zolpimist Rozerem Lunesta | Headache, somnolence, amnesia, fatigue |

Because gonadal hormonal dysregulation is implicated in the genesis of PMS symptoms, ovulation suppression is another option. There is some data to support combination oral contraceptive (COC) pills in general for premenstrual mood symptoms. Moreover, in randomized trials, Yasmin, a COC containing the spironolactone-like progestin drospirenone, showed therapeutic benefits. It carries an FDA indication for PMDD treatment in women who desire contraception (Pearlstein, 2005; Yonkers, 2005). Alternatively, GnRH agonists are another means of ovulation suppression. These agents are infrequently selected due to their hypoestrogenic side effects and risks. If elected for PMDD and used longer than 6 months, add-back therapy, as discussed in Chapter 10, can potentially blunt these side effects. Rarely, symptoms warrant bilateral oophorectomy, and a trial of GnRH agonists prior to surgery may be prudent to determine the potential efficacy of castration. Last, the synthetic androgen danocrine (Danazol) also suppresses ovulation, but androgen-related acne and hair growth are usually poorly tolerated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree