NORMAL VAGINAL FLORA

The vaginal flora of a normal, asymptomatic reproductive-aged woman includes multiple aerobic, facultative anaerobic, and obligate anaerobic species (Table 3-1). Of these, anaerobes predominate and outnumber aerobic species approximately 10 to 1 (Bartlett, 1977). These bacteria exist in a symbiotic relationship with the host and are alterable, depending on the microenvironment. They localize where their survival needs are met and have exemption from the infection-preventing destructive capacity of the human host. The function of this vaginal bacterial colonization, however, remains unknown.

Aerobes

|

Anaerobes

|

Within this vaginal ecosystem, some microorganisms produce substances such as lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide that inhibit nonindigenous organisms (Marrazzo, 2006). Several other antibacterial compounds, termed bacteriocins, play a similar role. For protection from many of these toxic substances, a secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor is found in the vagina. This protein protects local tissues against toxic inflammatory products and infection.

Certain bacterial species normally found in vaginal flora have access to the upper reproductive tract. The female upper reproductive tract is not sterile, and the presence of these bacteria does not indicate active infection (Hemsell, 1989; Spence, 1982). Together, these findings do illustrate the potential for infection following gynecologic surgery and the need for antimicrobial prophylaxis. They also explain the potential acceleration of a local acute infection if a pathogen, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, gains access to the upper tract.

Typically, the vaginal pH ranges between 4 and 4.5. Although not completely understood, Lactobacillus species contribute by production of lactic acid, fatty acids, and other organic acids. Other bacteria can also add organic acids from protein catabolism, and anaerobic bacteria donate by amino acid fermentation.

Glycogen, which is present in healthy vaginal mucosa, provides nutrients for many vaginal ecosystem species and is metabolized to lactic acid (Boskey, 2001). Accordingly, as glycogen content within vaginal epithelial cells diminishes after menopause, this decreased substrate for acid production leads to a rise in vaginal pH. Specifically, if no pH-altering pathogens are present, a vaginal pH of 6.0 to 7.5 is strongly suggestive of menopause (Caillouette, 1997).

Changing any element of this ecology may alter the prevalence of various species. For example, postmenopausal women not receiving estrogen replacement and young girls have a lower prevalence of Lactobacillus species compared with that of reproductive-aged women. However, for menopausal women, hormone replacement therapy restores vaginal lactobacilli populations, which protect against vaginal pathogens (Dahn, 2008).

Other events predictably alter lower reproductive tract flora and may lead to infection. With the menstrual cycle, transient changes in flora are observed. These are predominantly during the first days of the cycle and are presumed to be associated with hormonal changes (Keane, 1997). Menstrual fluid can also serve as a nutrient source for several bacterial species, resulting in their overgrowth. What role this plays in the development of upper reproductive tract infection following menstruation is unclear, but an association may be present. For example, women symptomatic with acute gonococcal upper reproductive tract infection characteristically are menstruating or have just completed their menses. Last, treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic may result in symptoms attributed to inflammation from Candida albicans or other Candida spp by eradicating other balancing species in the flora.

This common, complex, and poorly understood clinical syndrome reflects abnormal vaginal flora. It has been variously named, and former terms are Haemophilus vaginitis, Corynebacterium vaginitis, Gardnerella or anaerobic vaginitis, and nonspecific vaginitis. With bacterial vaginosis (BV), the vaginal flora’s symbiotic relationship shifts for unknown reasons to one in which anaerobic species overgrow and include Gardnerella vaginalis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mobiluncus species, Mycoplasma hominis, and Prevotella species. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is also associated with a significant reduction or absence of normal hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species. Whether an altered ecosystem leads to lactobacilli disappearance or whether its disappearance results in the changes observed with BV is unclear.

In evaluating risks for BV, this condition is not considered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2015) to be a sexually transmitted disease (STD). However, an increased risk of BV is associated with sexual contact with multiple and new male and female partners, and condom use lowers the risk (Table 3-2) (Fethers, 2008). Further, rates of STD acquisition are increased in affected women, and a possible role of sexual transmission in the pathogenesis of recurrent BV has been proposed (Atashili, 2008; Bradshaw, 2006; Wiesenfeld, 2003). Successful prevention of BV is limited, but elimination or diminished use of vaginal douches may be beneficial (Brotman, 2008; Klebanoff, 2010).

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common cause of vaginal discharge among reproductive-aged women. Of symptoms, a nonirritating, malodorous vaginal discharge is characteristic, but may not always be present. The vagina is usually not erythematous, and cervical examination reveals no abnormalities.

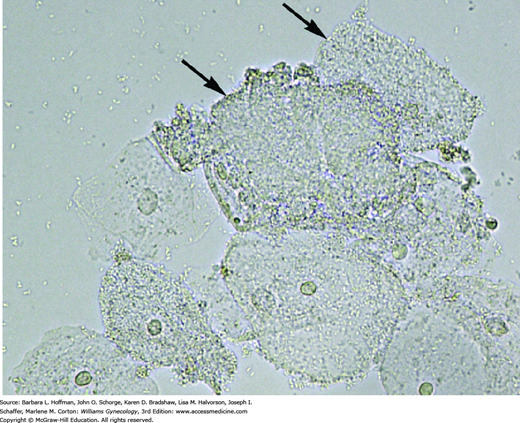

Clinical diagnostic criteria were first proposed by Amsel and associates (1983) and include: (1) microscopic evaluation of a vaginal-secretion saline preparation, (2) release of volatile amines produced by anaerobic metabolism, and (3) determination of the vaginal pH. A saline preparation, also known as a “wet prep,” contains a swab-collected sample of discharge mixed with drops of saline on a microscope slide. Clue cells are the most reliable indicators of BV and were originally described by Gardner and Dukes (1955) (Fig. 3-1). These vaginal epithelial cells contain many attached bacteria, which create a poorly defined stippled cellular border. At least 20 percent of the epithelial cells should be clue cells. The positive predictive value of this test for BV is 95 percent.

FIGURE 3-1

Photomicrograph of saline wet preparation reveals clue cells. Several of these squamous cells are heavily studded with bacteria. Clue cells are covered to the extent that cell borders are blurred and nuclei are not visible (arrows). (Used with permission from Dr. Lauri Campagna and Mercedes Pineda, WHNP.)

Adding 10-percent potassium hydroxide (KOH) to a fresh sample of vaginal secretions releases volatile amines that have a fishy odor. This is often colloquially referred to as a “whiff test.” The odor is frequently evident even without KOH. Similarly, alkalinity of seminal fluid and blood are responsible for foul-odor complaints after intercourse and with menses. The finding of both clue cells and a positive whiff test result is pathognomonic, even in asymptomatic patients.

Characteristically with BV, the vaginal pH is >4.5, and this stems from diminished acid production by bacteria. Similarly, Trichomonas vaginalis infection is also associated with anaerobic overgrowth and resultant elaborated amines. Thus, women diagnosed with BV should have no microscopic evidence of trichomoniasis.

Last, and used primarily in research studies rather than clinical practice, the Nugent Score is a system employed for diagnosing BV. During microscopic examination of a gram-stained vaginal discharge smear, scores are calculated by assessing bacteria staining and morphology.

Several gynecologic adverse health outcomes have been observed in women with BV. These include vaginitis, endometritis, postabortal endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) unassociated with N gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis, and acute pelvic infections following pelvic surgery, especially hysterectomy (Larsson, 1989, 1991, 1992; Soper, 1990). Pregnant patients with BV have an elevated risk of preterm delivery (Flynn, 1999; Leitich, 2007).

Several regimens have been proposed by the 2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention BV working group and are for nonpregnant women (Table 3-3). Cure rates with these regimens range from 80 to 90 percent at 1 week, but within 3 months, 30 percent of women have experienced a recurrence of altered flora. At least half have another episode of symptoms associated with this flora change, many of which are correlated with heterosexual contacts (Amsel, 1983; Gardner, 1955; Wilson, 2004). However, treatment of male sexual partners does not benefit women with this recurring condition and is not recommended. Moreover, other forms of therapy such as introduction of lactobacilli, acidifying vaginal gels, and use of probiotics have shown inconsistent effectiveness (Senok, 2009).

| Recommended regimens | |

| Metronidazole (Flagyl) Metronidazole gel 0.75% (Metrogel vaginal) Clindamycin creama 2% (Cleocin, Clindesse) | 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days 5 g (1 full applicator) intravaginally once daily for 5 days 5 g (1 full applicator) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days |

| Alternative regimens | |

| Tinidazole (Tindamax) Clindamycin Clindamycin ovules a (Cleocin) | 2 g orally once daily for 2 days 1 g orally once daily for 5 days 300 mg orally twice daily for 7 days 100 mg intravaginally at bedtime for 3 days |

ANTIBIOTICS

These drugs are commonly used in gynecology to restore altered flora or treat various infections. As a group, antibiotics have been implicated in decreasing the efficacy of oral contraceptives. Fortunately, this has been proven in very few, and these are listed in Table 5-9.

The heart of all penicillins is a thiazolidine ring with an attached β-lactam ring and a side chain. The β-lactam ring provides antibacterial activity, which is primarily directed against gram-positive aerobic bacteria. Because of the numerous substitutions at the side chain, various antibiotics with altered antibacterial spectra and pharmacologic properties have been synthesized.

Some bacteria produce an enzyme (β-lactamase) that opens the β-lactam ring and inactivates the drug as a primary bacterial defense mechanism. Inhibitors of β-lactamase are clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam, and these have been combined with several penicillins to enhance the activity spectrum against a broader variety of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Additionally, oral probenecid can be administered separately with penicillins. This drug lowers the renal-tubular secretion rate of these antibiotics and is used to increase penicillin or cephalosporin plasma levels.

Adverse reactions to penicillins may include allergic (e.g., anaphylaxis, urticaria, drug fever), neurologic (e.g., dizziness, seizure), hematologic (e.g., neutropenia, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia), renal (interstitial cystitis), hepatic (elevated transaminases), or gastrointestinal (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pseudomembranous colitis) reactions (Mayo Clinic, 1991). Up to 10 percent of the general population may manifest an allergic reaction to penicillins. The lowest risk is associated with oral preparations, whereas the highest follows those combined with procaine and given intramuscularly. True anaphylactic reactions are rare, and mortality rates approximate 1 in every 50,000 treatment regimens. If penicillin allergy is noted, yet treatment is still required, desensitization can be performed relatively safely as described by Wendel and coworkers (1985) and outlined at the CDC website: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/penicillin-allergy.htm.

Excellent tissue penetration is achieved with these agents. Penicillin remains the primary antibiotic for treatment of syphilis, and this antibiotic family is also useful in treating skin infections, breast cellulitis, and breast abscess. The combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (Augmentin) provides the best oral broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage. Moreover, the ureidopenicillins and those combined with a β-lactamase enzyme inhibitor are effective against acute community-acquired or postoperative pelvic infections. In addition, Actinomyces israelii infections, which are an infrequent complication of intrauterine device (IUD) use, are treated with penicillins (Westhoff, 2007).

Cephalosporins also are β-lactam antimicrobials. Substitutions at their side chains significantly alter the spectrum of activity, potency, toxicity, and half-life of these antibiotics. Organization of these qualities has resulted in their division into five generations. This classification does allow grouping based on general spectra of activity.

Rash and other hypersensitivity reactions are the most common and may develop in up to 3 percent of patients. Cephalosporins are β-lactam antibiotics and, if used in those allergic to penicillin, may create the same or accentuated response. Theoretically, this may happen in up to 16 percent of patients (Saxon, 1987). Thus, if an individual developed anaphylaxis with penicillin therapy, cephalosporin administration is contraindicated.

First-generation cephalosporins are used primarily for surgical prophylaxis and in the treatment of superficial skin cellulitis. Their activity spectrum is greatest against gram-positive aerobic cocci, with some activity against community-acquired gram-negative rods. However, there is little activity against β-lactamase producing organisms or anaerobic bacteria. Despite this inactivity against many pathogens of pelvic infection that may be acquired during surgery, there is prophylactic efficacy.

Second-generation cephalosporins have enhanced activity against gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, with some diminution in effectiveness against aerobic gram-positive cocci. Their primary use is in surgical prophylaxis or for single-agent therapy of major community-acquired or postoperative pelvic infections, including abscess.

Third-generation cephalosporins provide gram-positive activity, even greater gram-negative coverage, and some anaerobic effects. Fourth-generation agents have a similar profile but are less susceptible to β-lactamases. Last, fifth-generation drugs, such as ceftaroline, share a similar profile but also cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). All three groups are effective in treatment of major postoperative pelvic infections, including abscess. These agents have documented efficacy as prophylactic agents, but should be reserved for therapy.

This family of compounds includes gentamicin, tobramycin, netilmicin, and amikacin. Gentamicin is primarily selected because of its low cost and clinical efficacy for pathogens recovered from pelvic infections. For gynecologists, it may be combined with clindamycin with or without ampicillin as a regimen for treatment of serious pelvic infections. Alternatively, gentamicin may be joined with ampicillin and metronidazole. Last, it can be used as adjuvant-agent for outpatient pyelonephritis. Aminoglycoside antibacterial activity is related to its serum/tissue concentration, and the higher the concentration, the greater the potency.

Aminoglycosides have the potential for significant patient toxicity, which can include ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and neuromuscular blockade. The inner ear is particularly susceptible to aminoglycosides because of selective accumulation within the hair cells and prolonged half-life within inner ear fluids. Those with vestibular toxicity complain of headaches, nausea, tinnitus, and loss of equilibrium. Cochlear toxicity leads to high-frequency hearing loss. If either of these develops, aminoglycoside administration is stopped promptly. Ototoxicity may be permanent, and risk correlates positively with therapy dose and duration.

Nephrotoxicity is reversible and may develop in up to 25 percent of patients (Bertino, 1993). Risk factors include older age, renal insufficiency, hypotension, volume depletion, frequent dosing intervals, treatment for 3 or more days, multiple antibiotic administration, or multisystem disease. Toxicity leads to a nonoliguric decrease in creatinine clearance and resultant rise in serum creatinine levels.

Neuromuscular blockade is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication and is dose-related. This family of antibiotics inhibits presynaptic acetylcholine release, blocks acetylcholine receptors, and prevents presynaptic calcium absorption. For this reason, aminoglycoside contraindications include myasthenia gravis or concurrent succinylcholine use. Blockade frequently follows rapid intravenous infusion. For this reason, aminoglycosides are ideally given intravenously over at least 30 minutes. Toxicity is usually detected before respiratory arrest, and at its first signs, intravenous calcium gluconate is administered to reverse this form of aminoglycoside toxicity.

Because of these potential adverse reactions, consideration must be given to dosing regimen. In those with normal renal function, aminoglycosides are commonly given parenterally every 8 hours. In those with reduced renal function, doses are reduced, intervals are lengthened, or both. To monitor serum concentration, provide adequate therapeutic levels, and prevent toxicity in patients given multiple daily doses, serum aminoglycoside concentrations are measured at peak (30 minutes after a 30-minute infusion or 1 hour after intramuscular [IM] injection) and at trough (immediately before a next dose). For gentamicin, tobramycin, and netilmicin, peak range ideally is 4 to 6 μg/mL, and troughs are 1 to 2 μg/mL. For amikacin, peaks and troughs are 20 to 30 μg/mL and 5 to 10 μg/mL, respectively.

Once-daily dosing has been evaluated and found to be as or less toxic than multiple daily dosing without sacrificing clinical efficacy (Bertino, 1993). Tulkens and colleagues (1988) reported that once-daily dosing of netilmicin was less toxic than administration three times daily, without jeopardizing efficacy in the treatment of women with PID. In 1992, Nicolau and associates presented pharmacokinetic data and a nomogram for administering aminoglycosides once daily, which starts with an initial dose based on creatinine clearance and subsequent dosing based on a random serum concentration drawn 8 to 12 hours later.

This is a third class of β-lactam antibiotics that differ from penicillins by changes to the thiazolidine ring attached to penicillin. The three antibiotics in this family are imipenem (Primaxin), meropenem (Merrem), and ertapenem (Invanz). Adverse reactions are comparable to those of the other β-lactam antibiotics. As is true with other β-lactams, if patients have experienced a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction to either a penicillin or cephalosporin, then a carbapenem should not be administered.

These antibiotics are designed for polymicrobial bacterial infections, primarily those with resistant aerobic gram-negative bacteria not susceptible to other β-lactam agents. They should be reserved to preserve efficacy by preventing the development of resistance.

The marketed monobactam, aztreonam, is a synthetic β-lactam. It has a spectrum of activity similar to that of aminoglycosides, that is, gram-negative aerobic species. Like other β-lactam antibiotics, these compounds inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding to penicillin-binding proteins or causing cell lysis. Aztreonam has affinity only for the binding proteins of the gram-negative bacteria and lacks affinity for either gram-positive bacteria or anaerobic organisms. For the gynecologist, aztreonam provides coverage for gram-negative aerobic bacteria, which is usually provided by aminoglycosides, for patients with significantly impaired renal function or aminoglycoside allergy.

This antibiotic is a workhorse in the treatment of serious gynecologic infections. Clindamycin is primarily active against aerobic gram-positive bacteria and most anaerobic bacteria, with little activity against aerobic gram-negative bacteria. It is also active against C trachomatis. N gonorrhoeae is moderately sensitive, and G vaginalis, which is typically present in BV, is very susceptible to clindamycin. It may be delivered by one of three routes: orally, intravenously, or vaginally (ovules or 2-percent cream).

The principal application of clindamycin for the gynecologist has been its combination with gentamicin and administration to women with serious community-acquired or postoperative soft-tissue infections or pelvic abscess. Its activity against MRSA has increased its use in these cases. Clindamycin is also used as monotherapy vaginally in the treatment of women with BV. Moreover, in women with early stages of hidradenitis suppurativa, some patients improve with long-term topical or oral clindamycin. Because there are parenteral and oral forms of this antibiotic, patients can transition from the more expensive parenteral therapy to oral therapy early.

This is a glycopeptide antibiotic that is active only against aerobic gram-positive bacteria. It is primarily used by the gynecologist to treat patients in whom β-lactam therapy is impossible due to a type 1 allergic reaction. Additionally, an oral dose of 120 mg every 6 hours can be given to patients who have developed antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile colitis and who do not respond to oral metronidazole. Last, vancomycin is often selected for MRSA infections.

Of adverse events, the most remarkable is the “red man” syndrome, which is a dermal reaction developing usually within minutes after initiation of a rapid drug infusion. The reaction, which is a response to histamine release, is an erythematous pruritic rash involving the neck, face, and upper torso. Hypotension also may develop. Intravenous administration over 1 hour or administration of an antihistamine may be protective, if given prior to infusion. Also associated with rapid administration may be painful back and chest muscle spasms.

The most significant of vancomycin’s side effects is nephrotoxicity, which is enhanced with aminoglycoside therapy, as is ototoxicity. Both are associated with high serum vancomycin concentrations. For this reason, serum peak and trough concentrations are recommended and ideally range between 20 and 40 μg/mL and 5 and 10 μg/mL, respectively. The initial dose is 15 mg/kg of ideal body weight. Other side effects include reversible neutropenia that may develop after prolonged use and peripheral intravenous-catheter-related thrombophlebitis.

This antibiotic is the principal therapy of trichomoniasis and commonly used for BV. Moreover, it is one of the mainstays of combination antimicrobial therapy given to women with serious postoperative or community-acquired pelvic infections, including pelvic abscess. Since it is active only against obligate anaerobes, metronidazole must be combined with agents effective against gram-positive and gram-negative aerobic bacterial species, such as ampicillin and gentamicin. It is as effective as vancomycin in the treatment of C difficile–associated pseudomembranous colitis.

Up to 12 percent of patients taking oral metronidazole may have nausea, and an unpleasant metallic taste has also been described. Patients should abstain from alcohol use to avoid a disulfiram-like effect and emesis. Peripheral neuropathy and convulsive seizures have been reported, are probably dose-related, and are rare.

Also known simply as quinolones, these antibiotics have become first-line agents for treating various infections because of their excellent bioavailability with oral administration, tissue penetration, broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, long half-lives, and good safety profile. As with cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones are separated into generations by their development, antibacterial activity, and pharmacokinetic properties.

Quinolones are contraindicated in children, adolescents, and pregnant and breastfeeding women because they may affect cartilage development. As a family, they are safe, and severe adverse reactions are rare. The side-effect rate ranges from 4 to 8 percent and primarily affects the gastrointestinal (GI) tract following oral administration. Central nervous system (CNS) symptoms such as headache, confusion, tremors, and seizures have been described, and these develop more frequently in patients with underlying brain disorders.

These agents are widely used by gynecologists to treat acute lower urinary tract infections and some sexually transmitted diseases. However, overuse has limited their usefulness in certain infections due to bacterial resistance (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). If a less expensive, safer, and equally effective alternative agent is available to treat a given infection, it should be used to preserve fluoroquinolone efficacy.

These bacteriostatic antimicrobials are commonly used orally and inhibit bacterial protein synthesis. Doxycycline, tetracycline, and minocycline are active against many gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, although their activity is greater against gram-positive species. Susceptible organisms also include several anaerobes, Chlamydia and Mycoplasma species, and some spirochetes. Accordingly, cervicitis, PID, syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, and granuloma inguinale respond to these agents. Moreover, tetracyclines are among treatment options for community-acquired skin and soft-tissue MRSA infections. Specifically, for these infections, minocycline and doxycycline are superior to tetracycline. Tetracycline is active against Actinomyces species and is an alternative for treating actinomycosis. Last, these antibiotics also bind specific nonmicrobial targets, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and are potent MMP inhibitors. As such, they provide antiinflammatory as well as antimicrobial activity for inflammatory conditions such as acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa.

With oral administration, tetracyclines can produce direct local GI irritation that manifests as abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. In teeth and growing bones, tetracyclines readily bind calcium, causing deformity, growth inhibition, or discoloration. Accordingly, tetracyclines are not prescribed for pregnant or nursing women or for children younger than 8 years. Sensitivity to sunlight or ultraviolet light may develop with use. Dizziness, vertigo, nausea, and vomiting may be seen with higher doses. In addition, thrombophlebitis frequently follows intravenous administration. Tetracyclines modify the normal GI flora, which can result in intestinal functional disturbances. Specifically, overgrowth of C difficile may lead to pseudomembranous colitis. Vaginal flora also may be altered with resultant Candida species overgrowth and symptomatic vulvovaginitis.

GENITAL ULCER INFECTIONS

Ulceration defines complete loss of the epidermal covering with invasion into the underlying dermis. In contrast, erosion describes partial loss of the epidermis without dermal penetration. These are distinguished by clinical examination. Biopsies are generally not helpful. But if taken, samples obtained from the edge of a new lesion are the most likely to be informative. Importantly, biopsy is mandatory if carcinoma is suspected, and Figure 4-2 illustrates technique.

Most young sexually active women in the United States who have genital ulcers will have herpes simplex infection or syphilis, but some will have chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, or granuloma inguinale. Essentially all are sexually transmitted and are associated with increased risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission. For this reason, HIV and other STD testing is offered to such patients. Sexual contacts require examination and treatment, and both require reevaluation following treatment.

Genital herpes is the most prevalent genital ulcer disease and is a chronic viral infection. The virus enters sensory nerve endings and undergoes retrograde axonal transport to the dorsal root ganglion, where the virus develops lifelong latency. Spontaneous reactivation by various events results in anterograde transport of viral particles/protein to the surface. Here virus is shed, with or without lesion formation. It is postulated that immune mechanisms control latency and reactivation (Cunningham, 2006).

There are two types of herpes simplex virus, HSV-1 and HSV-2. Type 1 HSV is the most frequent cause of oral lesions. Type 2 HSV is found more typically with genital lesions, although both types can cause genital herpes. It is estimated that of American females aged 14 to 49 years, 21 percent have suffered a genital HSV-2 infection, and 60 percent of women are seropositive to HSV-1 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; Xu, 2006).

Most women who have been infected with HSV-2 lack this diagnosis because of mild or unrecognized infections. Infected patients can shed infectious virus while asymptomatic, and most infections are transmitted sexually by patients who are unaware of their infection. Most (65 percent) with active infection are women.

Patient symptoms at initial presentation will depend primarily on whether or not a patient during the current episode has antibody from previous exposure. If a patient has no antibody, the attack rate in an exposed person approaches 70 percent. The mean incubation period is approximately 1 week. Up to 90 percent of those who are symptomatic with their initial infection will have another episode within a year.

The virus infects viable epidermal cells, the response to which is erythema and papule formation. With cell death and cell wall lysis, blisters form (Fig. 3-2). The covering then disrupts, leaving a usually painful ulcer. These lesions develop crusting and heal, but may become secondarily infected. The three stages of lesions are: (1) vesicle with or without pustule formation, which lasts approximately a week; (2) ulceration; and (3) crusting. Virus is predictably shed during the first two phases of an infectious outbreak.

Burning and severe pain accompany initial vesicular lesions. With ulcers, urinary frequency and/or dysuria from direct contact of urine with ulcers may be complaints. Local swelling can result from vulvar lesions and cause urethral obstruction. Alternatively or additionally, herpetic lesions can involve the vagina, cervix, bladder, anus, and rectum. Commonly, a woman has other signs of viremia such as a low-grade fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias.

Viral load undoubtedly contributes to the number, size, and distribution of lesions. Normal host defense mechanisms inhibit viral growth, and healing starts within 1 to 2 days. Early treatment with an antiviral medication decreases the viral load. Immune-deficient patients are at increased susceptibility but display diminished response and delayed healing.

For a previously uninfected patient, the vesicular stage is longer. The period of new lesion formation and time to healing are both longer. Pain persists for the first 7 to 10 days, and lesion healing requires 2 to 3 weeks. If a patient has had prior exposure to HSV-2, the initial episode is significantly less severe, with shorter pain and tenderness duration, and time to healing approximates 2 weeks. Virus is shed usually only during the first week.

Recurrence following HSV-2 infection is common, and almost two thirds of patients have a prodrome prior to lesion onset. Heralding paresthesias are frequently described as pruritus or tingling in the area prior to lesion formation. However, prodromal symptoms may develop without actual lesion formation. Clinical manifestations for women with recurrences are more limited, with only 1 week or less of symptoms.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of genital herpes is tissue culture. Specificity is high, but sensitivity is low and declines as lesions heal. In recurrent disease, less than 50 percent of cultures are positive. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of exudate swabbed from the ulcer is many times more sensitive than culture and will probably replace it. Importantly, a negative culture result does not mean that there is no herpetic infection.

Serologic testing may also add clarity. The herpes simplex virus is surrounded by envelope glycoproteins, and of these, glycoprotein G is the antigen of interest for antibody screening. Serologic assays can detect antibodies specific to the HSV type-specific glycoprotein G2 (HSV-2) and glycoprotein G1 (HSV-1). Assay specificity is ≥96 percent, and the sensitivity of HSV-2 antibody testing ranges from 80 to 98 percent. Importantly, with serologic screening, only IgG antibody assays are ordered. IgM testing can lead to ambiguous results as the IgM assays are not type-specific and also may be positive during a recurrent outbreak. Although these tests may be used to confirm herpes simplex infection, seroconversion following initial HSV-2 infection takes approximately 3 weeks (Ashley-Morrow, 2003). Thus, in clinically obvious cases, immediate treatment and additional STD screening can be initiated following physical examination alone. In general, STD screening for a woman found to have any STD typically includes testing directed to identify syphilis, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and HIV, chlamydial, and hepatitis B infections.

Serologic screening for HSV in the general population is not recommended. However, HSV serologic testing can be considered for HIV-infected individuals or for women presenting for an STD evaluation, especially for those with multiple partners and for those in demographics with high prevalence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). It can also add management information for couples thought but not confirmed to be discordant for infection (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2014b).

Clinical management is with currently available antiviral therapy. Analgesia with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or a mild narcotic such as acetaminophen with codeine may be prescribed. In addition, topical anesthetics such as lidocaine ointment may provide relief. Local care to prevent secondary bacterial infection is important.

Patient education is mandatory, and specific topics include the natural history of the disease, its sexual transmission, methods to reduce transmission, and obstetric consequences. Notably, HSV can be passed to the neonate during vaginal delivery through an infected field. A comprehensive discussion of obstetric management is found in Williams Obstetrics, 24th edition (Cunningham, 2014). For all women, acquisition of this infection may have significant psychological impact, and several websites provide patient information and support. The CDC website can be accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/std/Herpes/STDFact-Herpes.htm.

Women with genital herpes should refrain from sexual activity with uninfected partners when prodrome symptoms or lesions are present. Latex condom use potentially reduces the risk for herpetic transmission (Martin, 2009; Wald, 2005).

Currently available antiviral therapy includes acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), and valacyclovir (Valtrex). The CDC-recommended oral medications regimens are listed in Table 3-4. Although these agents may hasten healing and decrease symptoms, therapy does not eradicate latent virus or affect future rate of recurrent infections.

| First clinical episode |

| Acyclovir 400 mg three times daily for 7–10 days or Acyclovir 200 mg five times daily for 7–10 days or Famciclovir (Famvir) 250 mg three times daily for 7–10 days or Valacyclovir (Valtrex) 1 g twice daily for 7–10 days |

| Episodic therapy for recurrent disease |

| Acyclovir 400 mg three times daily for 5 days or Acyclovir 800 mg twice daily for 5 days or Acyclovir 800 mg three times daily for 2 days or Famciclovir 125 mg twice daily for 5 days or Famciclovir 1 g twice daily for 1 day or Famciclovir 500 mg once, then 250 mg twice daily for 2 days or Valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily for 3 days or Valacyclovir 1 g once daily for 5 days |

| Suppressive therapy |

| Acyclovir 400 mg twice daily or Famciclovir 250 mg twice daily or Valacyclovir 0.5 or 1 g once daily |

For women with established HSV-2 infection, therapy may not be necessary if their symptoms are minimal and tolerated by the patient. Episodic therapy for recurrent disease is ideally initiated at least within 1 day of lesion outbreak or during the prodrome, if it exists. Patients may be given a prescription ahead of time so that medication is available to begin therapy with prodromal symptoms.

If episodes recur at frequent intervals, a woman may elect daily suppressive therapy, which reduces recurrences by 70 to 80 percent. Suppressive therapy may eliminate recurrences and decreases sexual transmission of virus by approximately 50 percent (Corey, 2004). Once-daily dosing may result in enhanced compliance and decreased cost.

Syphilis is an STD caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, which is a slender spiral-shaped organism with tapered ends. Women at highest risk are those from lower socioeconomic groups, adolescents, those with early onset of sexual activity, and those with a large number of lifetime sexual partners. The attack rate for this infection approximates 30 percent. In 2011, more than 49,000 cases (all stages) of syphilis were reported by state health departments in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012).

The natural history of syphilis in untreated patients can be divided into four stages. With primary syphilis, the hallmark lesion is the chancre, in which spirochetes are abundant. Classically, it is an isolated nontender ulcer with raised rounded borders and an uninfected base (Fig. 3-3). However, it may become secondarily infected and painful. Chancres are often found on the cervix, vagina, or vulva but may also form in the mouth or around the anus. This lesion can develop 10 days to 12 weeks after exposure, with a mean incubation period of 3 weeks. The incubation period is directly related to inoculum size. Without treatment, these lesions spontaneously heal in up to 6 weeks.

With secondary syphilis, bacteremia develops 6 weeks to 6 months after a chancre appears. Its hallmark is a maculopapular rash that may involve the entire body and includes the palms, soles, and mucous membranes (Fig. 3-4). As is true for the chancre, this rash actively sheds spirochetes. In warm, moist body areas, this rash may produce broad, pink or gray-white, highly infectious plaques called condylomata lata. Because syphilis is a systemic infection, other manifestations may include fever and malaise. Moreover, organ systems such as the kidney, liver, joints, and CNS (meningitis) can be involved.

FIGURE 3-4

Secondary syphilis. A. Woman with multiple keratotic papules on her palms (arrows). With secondary syphilis, disseminated papulosquamous eruptions may be seen on the palms, soles, or trunk. (Used with permission from Dr. William Griffith.) B. Woman with multiple condyloma lata on her labia. Soft, flat, moist, pink-tan papules and nodules on the perineum and perianal area are typical. (Used with permission from Dr. George Wendel.)

During the first year following secondary syphilis without treatment, termed early latent syphilis, secondary signs and symptoms may recur. However, lesions associated with these outbreaks are not usually contagious. Late latent syphilis is defined as a period greater than 1 year after the initial infection.

Tertiary syphilis is the phase of untreated syphilis that may appear up to 20 years after latency. During this phase, cardiovascular, CNS, and musculoskeletal involvement become apparent. However, cardiovascular and neurosyphilis are half as common in females as in males.

Spirochetes are too thin to retain Gram stain. Early syphilis is diagnosed primarily by dark-field examination or direct fluorescent antibody testing of lesion exudate. In lieu of this, presumptive diagnosis may be reached with serologic tests that are nontreponemal: (1) Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) or (2) rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests. Alternatively, treponemal-specific tests may be selected: (1) fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) or (2) Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) tests. For population screening, RPR or VDRL testing is appropriate. A positive test result in a woman who has not been treated previously for syphilis or a fourfold titer (two dilutions) increase in a woman previously treated for syphilis should prompt confirmation with treponemal-specific tests. Thus, for diagnosis confirmation in a woman with a positive nontreponemal antibody test result or with a suspected clinical diagnosis, FTA-ABS or TP-PA testing is selected. Last, for quantitative measurement of antibody titers to assess response to treatment, RPR or VDRL tests are typically used.

Following treatment, sequential nontreponemal tests are performed. During this surveillance, the same type of test should be used for consistency—either RPR or VDRL. A fourfold titer decrease is required by 6 months after therapy for primary or secondary syphilis or within 12 to 24 months for those with latent syphilis or women with initially high titers (>1:32)(Larsen, 1998). These tests usually become nonreactive after treatment and with time. However, some women may have a persistent low titer, and these patients are described as serofast. Moreover, women with a reactive treponemal-specific test will more than likely have a positive test for the remainder of their lives, but up to 25 percent may revert to a negative result after several years.

Penicillin is the first-line therapeutic agent for this infection, and benzathine penicillin is primarily chosen. Specific recommendations for therapy by the CDC (2015) are listed in Table 3-5. For patients with penicillin allergy who cannot be surveilled posttherapy or whose compliance is questioned, skin testing, desensitization, and treatment with IM benzathine penicillin is recommended (Wendel, 1985). For all patients, an acute, self-limited febrile response, termed a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, may develop within the first 24 hours after treatment of early disease and is associated with headache and myalgia.

| Primary, secondary, early latent (<1 year) syphilis |

|

| Late latent, tertiary, and cardiovascular syphilis |

|

As with other STDs, all patients treated for syphilis and their sexual contacts are screened for other STDs. Patients with evidence of neurologic or cardiac involvement are treated by an infectious disease specialist. After initial treatment, women are seen at 6-month intervals for clinical evaluation and serologic retesting. A fourfold dilution decrease is anticipated. If this does not occur, a patient either has failed treatment or was reinfected and should be reevaluated and retreated. Retreatment recommendations are benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units IM weekly for 3 weeks.

This is considered one of the classic STDs but is an uncommon infection in the United States. It appears as local outbreaks predominantly in black and Hispanic males. It is caused by a nonmotile, non-spore-forming, facultative, gram-negative bacillus, Haemophilus ducreyi. Incubation usually spans 3 to 10 days, and host access probably requires a break in the skin or mucous membrane.

Chancroid lacks a systemic reaction and prodrome. Infection presents initially with an erythematous papule that becomes pustular and ulcerates within 48 hours. Edges of these painful ulcers are usually irregular with erythematous nonindurated margins. The ulcer bases are usually red and granular and, in contrast to a syphilitic chancre, are typically soft. Lesions are frequently covered with purulent material and may become secondarily infected. The most common locations in women include the fourchette, vestibule, clitoris, and labia. Ulcers on the cervix or vagina may be nontender. Concurrently, approximately half of patients will develop unilateral or bilateral tender inguinal lymphadenopathy. If large and fluctuant, they are termed buboes. These may occasionally suppurate and form fistulas, the drainage from which will result in other ulcer formation.

Chancroid most commonly imitates syphilis and genital herpes. These may coexist, but uncommonly. Definitive diagnosis requires growth of H ducreyi on special media, but sensitivity for culture is less than 80 percent. A presumptive diagnosis can be made with identification of gram-negative, nonmotile rods on a Gram stain of lesion contents. Before obtaining either specimen, superficial pus or crusting ideally is removed with sterile, saline-soaked gauze.

For treatment, the CDC’s (2015) recommended regimens for nonpregnant women include single doses of oral azithromycin (1 g) or IM ceftriaxone (250 mg). Multiple-dose options are ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally twice daily for 3 days or erythromycin base 500 mg orally three times daily for 7 days. Successful treatment leads to symptomatic improvement within 3 days, and objective evidence of improvement within 1 week. Lymphadenopathy resolves more slowly, and if fluctuant, incision and drainage may be warranted. Those with coexisting HIV infection may require longer therapy courses, and treatment failures are more common. Accordingly, some recommend longer regimens for initial management of known HIV-infected patients.

Also known as donovanosis, granuloma inguinale genital ulcerative disease is caused by the intracellular gram-negative bacterium Calymmatobacterium (Klebsiella) granulomatis. This bacterium is encapsulated and appears as a “closed safety pin” in stained tissue biopsy or cytology specimens. Apparently this disease is only mildly contagious, requires repeated exposures, and has a long incubation period of weeks to months.

Granuloma inguinale presents as painless inflammatory nodules that progress to highly vascular, beefy red ulcers that bleed easily on contact. If secondarily infected, they may become painful. These ulcers heal by fibrosis, which can result in scarring resembling keloids. Lymph nodes are usually uninvolved but can become enlarged, and new lesions can appear along these lymphatic drainage channels. Distant lesions have also been reported.

Diagnosis is confirmed by identification of Donovan bodies during microscopic evaluation of a specimen following Wright-Giemsa staining. Currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved PCR tests for C granulomatis DNA.

Treatment does stop lesion progression and may be lengthy without formation of granulation tissue in ulcer bases and reepithelialization (Table 3-6). Relapses have been reported up to 18 months after “effective” treatment. A few prospective treatment trials have been published, but these are limited. If successful, improvement will be evident within the first few treatment days.

| Recommended regimen |

|

| Alternative regimens |

|

This ulcerative genital disease is caused by trachomatis serotypes L1, L2, and L3 and is uncommon in the United States. As is true with other STDs, this infection is found in lower socioeconomic groups among persons with multiple sexual partners. Incubation ranges from 3 days to 2 weeks, and its clinical course is divided into three stages: (1) small vesicle or papule, (2) inguinal or femoral lymphadenopathy, and (3) anogenitorectal syndrome. Initial papules appear primarily on the fourchette and posterior vaginal wall up to and including the cervix. Repeated inoculation may result in lesions at multiple sites. These primary lesions heal quickly and without scarring.

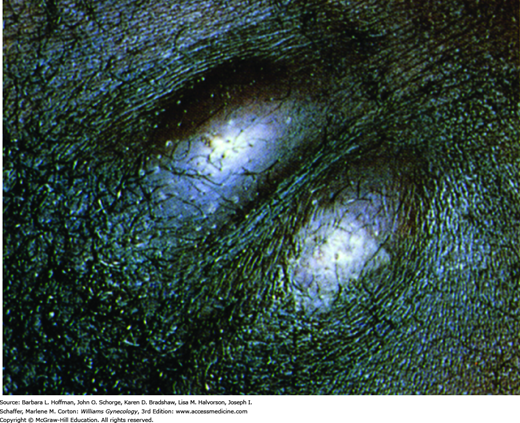

During the second stage, sometimes referred to as the inguinal syndrome, inguinal and femoral lymph nodes progressively enlarge. Painful nodes can mat together on either side of the inguinal ligament and create a characteristic “groove sign,” which appears in up to one fifth of infected women (Fig. 3-5). Moreover, enlarging nodes may rupture through the skin and lead to chronically draining sinuses. Women with lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) commonly develop systemic infection, manifest by malaise and fever. Additionally, pneumonitis, arthritis, and hepatitis have been reported.

FIGURE 3-5

“Groove sign” seen with lymphogranuloma venereum. Enlarged lymph nodes matted together on either side of the inguinal ligament create this characteristic groove. (Reproduced with permission from Morse S, Ballard RC, Holmes KK, et al (eds): Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003.)

In the third stage of LGV, a patient develops rectal pruritus and a mucoid discharge from rectal ulcers. If these become infected, the discharge turns purulent. This presentation stems from lymphatic obstruction that follows lymphangitis and that may result in elephantiasis of external genitalia initially and fibrosis of the rectum. Stenosis of the urethra and the vagina has also been reported. Rectal bleeding is common, and a woman may complain of crampy, abdominal pain with abdominal distention, rectal pain, and fever. Peritonitis may follow bowel perforation.

LGV may be diagnosed following clinical evaluation with exclusion of other etiologies and positive chlamydial testing. Specifically, culture or immunofluorescence or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) testing of samples from genital lesions, affected lymph nodes, or rectum are suitable. Moreover, a chlamydial serologic titer that is >1:64 can support the diagnosis.

For treatment, the CDC-recommended regimen (2015) is doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily for 21 days. Alternatively, one may use erythromycin base 500 mg orally four times daily for the same duration. Sexual contacts exposed to a patient within the prior 60 days are tested for urethral or cervical infection and treated with either standard anti-chlamydial regimen.

INFECTIOUS VAGINITIS

Symptomatic vaginal discharge most often reflects BV, candidiasis, or trichomoniasis. Bacterial vaginosis typically evokes complaints of foul discharge odor. In contrast, if abnormal discharge is associated with vulvar burning, irritation, or itching, then vaginitis is diagnosed. Between 7 and 70 percent of women who have vaginal discharge complaints will have no definitive diagnosis (Anderson, 2004). For those in whom identifiable infection is absent, an inflammatory diagnosis and treatment for infection should not be given. In such instances, a woman may seek reassurance, having concern about a recent sexual exposure, and STD screening may alleviate this.

Importantly, during evaluation, a clinician obtains a complete history regarding prior vaginal infections and their treatment, symptom duration, specifics of self-treatment with over-the-counter (OTC) preparations, and a complete menstrual and sexual history. The salient features of a menstrual history are outlined in Chapter 8. A sexual history typically includes questions regarding age at coitarche, date of most recent sexual activity, number of recent partners, gender of those partners, use of condom barrier protection, method of birth control, prior STD history, and type of sexual activity—anal, oral, or vaginal.

A thorough physical examination of the vulva, vagina, and cervix is also performed. Several etiologies may be identified in the office by microscopic examination of the discharge (Table 3-7). First, a saline preparation, described earlier, can be inspected. In contrast, a “KOH-prep” contains a swab-collected sample of discharge mixed with several drops of 10-percent potassium hydroxide (KOH). KOH leads to osmotic swelling and then lysis of squamous cell membranes. This visually clears the microscopic view and aids identification of fungal buds or hyphae. Finally, vaginal pH analysis may add supportive information. Vaginal pH can be estimated using chemical testing paper strips. Appropriate readings are obtained by pressing a test strip directly to the upper vaginal wall and resting it there for a few seconds to absorb vaginal fluid. Once the strip is removed, its color is determined and matched to a color indicator chart on the test strip dispenser. Importantly, blood and semen are alkaline and often will artificially elevate pH. Unfortunately, inexpensive laboratory tests such as these are not as accurate as a clinician would hope (Bornstein, 2001; Landers, 2004).

| Category | Complaint | Discharge | KOH “Whiff Test” | Vaginal pH | Microscopic Findings |

| Normal | None | White, clear | – | 3.8–4.2 | NA |

| BV | Odor, increased after intercourse and/or menses | Thin, gray or white, adherent, often increased | + | >4.5 | Clue cells, bacteria clumps (saline wet prep) |

| Candidiasis | Itching, burning, discharge | White, curdy | – | <4.5 | Hyphae and buds (10-percent KOH solution wet prep) |

| Trichomoniasis | Frothy discharge, odor, dysuria, pruritus, spotting | Green-yellow, frothy, adherent, increased | ± | >4.5 | Motile trichomonads (saline wet prep) |

| Bacterial a | Thin, watery discharge, pruritus | Purulent | – | >4.5 | Many WBCs |

This infection is most commonly caused by Candida albicans, which can be found in the vagina of asymptomatic patients and is a commensal of the mouth, rectum, and vagina. Occasionally, other Candida species may be involved and include C tropicalis and C glabrata, among others. Candidiasis is seen more often in warmer climates and in obese patients. Additionally, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, and recent broad-spectrum antibiotic use predispose women to clinical infection. It can be sexually transmitted, and several studies have reported an association between candidiasis and orogenital sex (Bradshaw, 2005; Geiger, 1996).

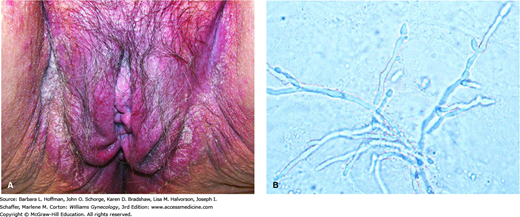

With candidiasis, pruritus, pain, vulvar erythema, and edema with excoriations are frequent findings (Fig. 3-6). The typical vaginal discharge is described as curdy or cottage cheese-like. Microscopic examination of vaginal discharge with saline and with 10-percent KOH preparations allows yeast identification. Candida albicans is dimorphic, with both yeast buds and hyphal forms. It may be present in the vagina as a filamentous fungus (pseudohyphae) or as germinated yeast with mycelia. Vaginal candidal culture is not routinely recommended. However, it may be warranted for those who fail empiric treatment and for women with evidence of infection yet absence of microscopic yeast.

FIGURE 3-6

Candidal infection. A. Thick white discharge, labial erythema, and edema are seen with candidiasis. (Used with permission from Dr. William Griffith.) B. Candida albicans in a potassium hydroxide preparation. Serpentine pseudohyphae are seen. (Reproduced with permission from Hansfield HH: Vaginal infections. In Color Atlas and Synopsis of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2001, p 169.)

The CDC classifies vulvovaginal candidiasis (2015) into “uncomplicated” and “complicated.” Uncomplicated candidiasis cases are sporadic or infrequent, mild to moderate in symptom severity, likely caused by Candida albicans, and involve nonimmunocompromised women. For both uncomplicated and complicated infection, effective treatment formulations are listed in Table 3-8. For uncomplicated infection, azoles are extremely effective, and women warrant specific follow-up only if therapy is unsuccessful.

| Drug | Brand Name | Formulation | Dosage |

| Butoconazole | Gynazole-1 a Mycelex-3 | 2% vaginal cream 2% vaginal cream | 1 app (5 g) vaginally ×1 d 1 app (5 g) vaginally ×3 d |

| Clotrimazole | Gyne-Lotrimin 7, Mycelex-7 Gyne-Lotrimin 3 Gyne-Lotrimin 3 | 1% vaginal cream 2% vaginal cream 200 mg vaginal supp | 1 app vaginally for 7 d 1 app vaginally for 3 d 1 vaginal supp daily for 3 d |

| Clotrimazole combination pack | Gyne-Lotrimin 3 Mycelex-7 | 200 mg supp + 1% topical cream 100 mg supp + 1% topical cream | 1 supp daily for 3 d. Use cream externally as needed 1 supp daily for 7 d. Use cream externally as needed |

| Clotrimazole + betamethasone | Lotrisone a | 1% clotrimazole with 0.05% betamethasone vaginal cream | Apply cream topically twice daily b |

| Miconazole | Monistat-7 Monistat Monistat-3 Monistat-7 | 100 mg vaginal supp 2% topical cream 4% vaginal cream 2% topical cream | 1 supp daily for 7 d Apply externally as needed 1 app vaginally for 3 d 1 app vaginally for 7 d |

| Miconazole combination pack |