ANAL INCONTINENCE

Although definitions are inconsistent, anal incontinence (AI) is most commonly defined as an involuntary loss of flatus, liquid, or solid stool that causes a social or hygienic problem (Abrams, 2005; Haylen, 2010). The definition of AI includes incontinence of flatus, whereas that of fecal incontinence (FI) does not.

Despite acceptance of these by healthcare professionals, one survey observed that only 30 percent of nearly 1100 community-dwelling women with FI had heard the term “fecal incontinence,” and 71 percent preferred the term “accidental bowel leakage” (Brown, 2012). Thus, at a recent consensus workshop, this latter more patient-centered term was suggested for use with patients (Bharucha, 2015).

AI can lead to poor self-image and isolation, and the social and quality-of-life effects of AI are significant (Johanson, 1996). Additionally, AI increases the likelihood that an older patient will be admitted to a nursing home rather than cared for at home (Grover, 2010).

Anal incontinence is common, and rates among men and women are similar (Madoff, 2004b; Nelson, 2004). In one National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), FI was also not significantly associated with race or ethnicity, education level, income, or marital status (Whitehead, 2009). Although all age groups may be affected, the AI prevalence increases with age and may reach 46 percent in older, institutionalized women (Nelson, 1998). Using data from NHANES that incorporated years 2005 through 2010, investigators noted that the prevalence of FI in women approximated 9 percent (Nygaard, 2008; Wu, 2014). Similarly, the estimated prevalence of FI in noninstitutionalized U.S. adults was 8.3 percent (18 million). Of these individuals, liquid stool incontinence was noted in 6.2 percent, mucus in 3.1 percent, and solid stool in 1.6 percent (Whitehead, 2009). The prevalence of FI increased from 2.6 percent in those aged 20 to 30 years and rose to 15.3 percent in subjects aged 70 years or older.

Normal defecation and anal continence are complex processes that require: (1) a competent anal sphincter complex, (2) normal anorectal sensation, (3) adequate rectal capacity and compliance, and (4) conscious control. Logically, mechanisms responsible for FI include anal sphincter and pelvic floor weakness, reduced or increased rectal sensation, reduced rectal capacity and compliance, and diarrhea (Bharucha, 2015). In many patients these factors may be additive, and thus no single physiologic measure is consistently associated with FI.

Essential contributors to fecal continence include the internal and external anal sphincters and the puborectalis muscle (Figs. 38-9 and 38-21). Of these, the internal anal sphincter (IAS) is the thickened distal 3- to 4-cm longitudinal extension of the colon’s circular smooth-muscle layer. It is innervated by the autonomic nervous system and provides 70 to 85 percent of the anal canal’s resting pressure (Frenckner, 1975). As a result, the IAS contributes substantially to the maintenance of fecal continence at rest.

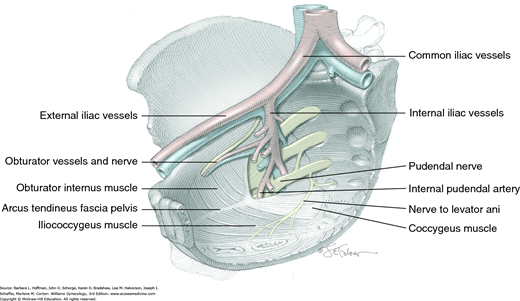

The external anal sphincter (EAS) consists of striated muscle and is primarily innervated by somatic motor fibers that course in the inferior rectal branch of the pudendal nerve (Fig. 25-1A). The EAS provides the anal canal’s squeeze pressure and is mainly responsible for maintaining fecal continence when continence is threatened. At times, squeeze pressure may be voluntary or may be induced by increased intraabdominal pressure. In addition, although resting sphincter tone is generally attributed to the IAS, the EAS maintains a constant state of resting contraction and may be responsible for approximately 25 percent of anal resting pressure. During defecation, however, the EAS relaxes to allow stool passage.

The puborectalis muscle is part of the levator ani muscle group and is innervated from its pelvic surface by direct efferents from the third, fourth, and fifth sacral nerve roots (Fig. 25-1B) (Barber, 2002). Although the suggestion is controversial, it may also be innervated from its perineal surface by the inferior rectal branch of the pudendal nerve. Its constant tone contributes to the anorectal angle, which aids in preventing rectal contents from entering the anus (Fig. 38-10). Similar to the EAS, this muscle can be contracted voluntarily or in response to sudden increases in abdominal pressure.

The role of the puborectalis in maintaining stool continence remains unclear. However, it is best appreciated in women who remain continent of solid stool despite absence of the anterior arch of the external and internal sphincters, as can be seen in those with chronic fourth-degree lacerations (Fig. 25-2). With normal puborectalis relaxation, evacuation is generally aided by the better longitudinal alignment of the rectoanal lumen. Conversely, paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle during defecation may lead to impaired evacuation. Moreover, atrophy of this muscle has been associated with FI (Bharucha, 2004).

Innervation to the rectum and anal canal is derived from the inferior hypogastric nerve plexus that contain sympathetic and parasympathetic components and by intrinsic nerves present in the rectoanal wall (Fig. 38-13, p. 806). In addition, the inferior rectal branch of the pudendal nerve conveys sensory input from the lower anal canal and the skin around the anus. Sensory receptors within the anal canal and pelvic floor muscles can detect the presence of stool in the rectum and the degree of distention. Through these neural pathways, information regarding rectal distention and rectal contents can be transmitted and processed and the action of the sphincteric musculature coordinated.

The rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) refers to the transient relaxation of the IAS and contraction of EAS induced by rectal distention when stool first arrives in the rectum. This reflex is mediated by the intrinsic nerves in the anorectal wall and allows the sensory-rich upper anal canal to come in contact with or “sample” the rectal contents (Whitehead, 1987). Specifically, sampling refers to the process whereby the IAS relaxes, often independently of rectal distention, allowing the anal epithelium to ascertain whether rectal contents are gas, liquid, or solid stools (Miller, 1988).

Following integration of this neural information, defecation can ensue in the appropriate social setting. Alternatively, if required, defecation can generally be postponed, as the rectum can accommodate its contents and the EAS or puborectalis muscle or both can be voluntarily contracted. However, if rectal sensation is impaired, contents may enter the anal canal and may leak before the EAS can contract (Buser, 1986).

Evaluation of the RAIR may clarify the underlying etiology of AI. This reflex is absent in those with congenital aganglionosis (Hirschsprung disease) but preserved in patients with cauda equina lesions or after spinal cord transection (Bharucha, 2006).

Following anal sampling, the rectum can relax to admit the increased rectal volume in a process known as accommodation. The rectum is a highly compliant reservoir that permits stool storage. As rectal volume increases, an urge to defecate is perceived. If this urge is voluntarily suppressed, the rectum relaxes to continue stool accommodation. A loss of compliance may decrease the ability of the rectal wall to stretch or accommodate, and as a result, rectal pressure may remain high. This may place increased demands on the other components of the continence mechanism such as the anal sphincter complex.

Rectal compliance can be calculated by measuring the sensitivity to and maximal volume tolerated from a fluid-filled balloon during anorectal manometry. Rectal compliance may be decreased in those with ulcerative and radiation proctitis. In contrast, increased compliance may be noted in certain patients with constipation, potentially signaling a megarectum.

Abnormal defecation develops if any of the just-described components of anal continence are altered. Logically, causes of AI and defecatory disorders are diverse and are likely multifactorial (Table 25-1).

| Obstetric | |

| Increasing parity | Anal sphincter damage |

| Medical conditions | |

| Obesity Aging Smoking Postmenopausal Medications Decreased activity | Diabetes mellitus COPD Chronic hypertension Stroke Scleroderma Pelvic radiation |

| Urogynecologic | |

| Urinary incontinence | Pelvic organ prolapse |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Constipation Diarrhea Fecal urgency Food intolerance IBS | Anal abscess Anal fistula Anal surgery Cholecystectomy Rectal prolapse |

| Neuropsychiatric | |

| Spinal cord lesion Parkinson disease Spinal surgery Multiple sclerosis Brain tumor | Myopathies Psychosis Nerve stretch injury Cognitive dysfunction |

In younger, reproductive-aged women, the most common association with AI is vaginal delivery and damage to the anal sphincter muscles (Snooks, 1985; Sultan, 1993; Zetterstrom, 1999). This damage may be mechanical or neuropathic and can result in fecal and flatal incontinence at an early age. Interestingly, the incidence of FI following vaginal delivery has declined from 13 percent of primiparous women two decades ago to 8 percent in more recent series (Bharucha, 2015). This may reflect changes in obstetric practices that include decreased use of instrumented vaginal delivery and more restricted episiotomy use.

Rates of sphincter tear during vaginal births in the United States range from 6 to 18 percent (Fenner, 2003; Handa, 2001). In one study of primiparas delivered at term, at both 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum, women who sustained anal sphincter tears during vaginal delivery had twice the risk of FI and reported more severe FI compared with women who delivered vaginally without evidence of sphincter disruption (Borello-France, 2006). In contrast, a retrospective study of 151 women with diverse obstetric histories who delivered 30 years previously reported that women with a prior sphincter disruption were more likely to have “bothersome” flatal incontinence but were not at increased risk for FI compared with women who had an isolated episiotomy or those who underwent cesarean delivery (Nygaard, 1997). Thus, other mechanisms associated with pregnancy and with aging may contribute to AI regardless of delivery mode or anal sphincter disruption. Importantly, cesarean delivery minimizes the risk of anatomic anal sphincter injury, but it does not universally protect against later AI. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2006) consensus conference on cesarean delivery on maternal request concluded that evidence was insufficient to support a practice of elective cesarean delivery for the prevention of pelvic floor disorders, including FI.

Few epidemiological studies have evaluated the risk factors for FI in the community. That said, underlying bowel disturbances, particularly diarrhea; the symptom of rectal urgency; and burden of chronic illness, are the strongest independent risk factors for FI (Bharucha, 2015). Inflammatory bowel conditions, especially with chronic diarrhea, are another common risk. Liquid stool is more difficult to control than solid, and thus FI may develop even if all components of the continence mechanism are grossly intact. Alternatively, chronic constipation with straining to defecate may damage the muscular and/or neural components of the sphincter mechanism. Similarly, other neuromuscular injury to the puborectalis and/or anal sphincter muscles, such as that associated with pelvic organ prolapse, may lead to AI.

Radiation therapy involving the rectum can result in poor compliance and loss of accommodation. Also, nervous system dysfunction in those with spinal cord injury, back surgery, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, or cerebrovascular accident may lead to poor accommodation, loss of sensation, impaired reflexes, and myopathy. Finally, loss of rectal sensation and decreased squeeze sphincter pressures can be seen with normal aging. One study suggests that even asymptomatic older nulliparous women have anal sphincter neurogenic injury, which partly explained weak anal squeeze pressures (Bharucha, 2012).

There is no current consensus on how best to screen for FI. Proposed barriers include poor patient understanding of the term FI, embarrassment, a belief that FI is a normal part of aging, confusion as to whom they might discuss the problem with, priority of other medical conditions, and unfamiliarity or pessimism regarding treatment options (Bharucha, 2015). In one study, less than one third of patients with FI had disclosed this to a provider (Johanson, 1996). In another that evaluated women presenting for benign gynecologic care, only 17 percent with FI were asked about the symptom by their health care provider (Boreham, 2005).

In contrast to urinary incontinence, no FI classification approach is widely accepted. However, the type (urge, passive, or mixed), etiology, and severity of FI provide some basis to categorize FI. A complete history and physical examination evaluates these prior to treatment planning and often identifies correctable problems.

To the patient, relevant questions are posed regarding incontinence duration and frequency, stool consistency, timing of incontinent episodes, use of sanitary protection, and incontinence-related social impairment. Additionally, risk factors noted in Table 25-1 are sought. Importantly, urge-related AI is differentiated from incontinence without awareness, as these may be associated with different underlying pathologies. For example, urgency without incontinence may reflect inability of the rectal reservoir to store stool rather than a sphincteric disorder.

To gather historical data, validated questionnaires, stooling diaries, and the Bristol Stool Scale are objective options. Of these, a patient diary of stool habits is commonly used in research, but its utility is often limited by poor patient adherence. Alternatively, questionnaires reduce patient recall bias and help standardize AI scores. Several incontinence-scoring systems provide objective measure of a patient’s degree of incontinence. Four commonly used symptom severity scores are the Pescatori Incontinence Score; Wexner (Cleveland Clinic) Score; St. Marks (Vaizey) Score; and the Fecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) (Tables 25-2 and 25-3) (Jorge, 1993; Pescatori, 1992; Rockwood, 1999; Vaizey, 1999). All of these incorporate the type and frequency of leakage. Of these, the Vaizey Score and the FISI include symptom weighting. The inclusion of patient-assigned severity scores increases the utility of the FISI compared with other scales. The ability of the Vaizey Score to incorporate a component of fecal urgency makes this scale desirable in certain clinical trials.

| Never a | Rarely b | Sometimes c | Weekly d | Daily e | |

| Incontinence for solid stool | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Incontinence for liquid stool | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Incontinence for gas | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Alteration in lifestyle | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| No | Yes | ||||

| Need to wear a pad or plug | 0 | 2 | |||

| Taking constipating medicines | 0 | 2 | |||

| Lack of ability to defer defecation for 15 minutes | 0 | 4 | |||

In addition to symptom severity, the patient’s quality-of-life decline from AI is also characterized. The validated fecal incontinence quality-of-life (FI-QOL) questionnaire is a 29-item tool designed to estimate associated worsening lifestyle, coping behavior, depression/self-perception, and embarrassment (Table 25-4) (Rockwood, 2000). Other quality-of-life scales available include the Modified Manchester Health Questionnaire and the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (Kwon, 2005; Sailer, 1998). These validated tools may be used diagnostically and also following treatment to determine response.

| Scale 1: Lifestyle | |

| I am afraid to go out | I avoid traveling |

| I avoid visiting friends | I avoid traveling by plane or train |

| I avoid many things I want to do | I avoid staying overnight away from home |

| I plan my schedule around my bowel pattern | I avoid going out to eat |

| It is difficult for me to get out and do things | I limit how much I eat before I go out |

| Scale 2: Coping/Behavior | |

| I feel I have no control over my bowels | I have sex less often than I would like to |

| I worry about bowel accidents | I worry about not reaching the toilet in time |

| The possibility of bowel accidents is always on my mind | |

| Whenever I go someplace new, I specifically locate where the bathrooms are | |

| I try to prevent bowel accidents by staying very near a bathroom | |

| I can’t hold my bowel movement long enough to get to the bathroom | |

| Whenever I am away from home, I try to stay near a restroom as much as possible | |

| Scale 3: Depression/Self-perception | |

| In general, how would you say your health is? | I feel different from other people |

| I am afraid to have sex | I enjoy life less |

| I feel depressed | I feel like I am not a healthy person |

| During the past month, have you felt so sad, discouraged, hopeless, or had so many problems that you wondered if anything was worthwhile? | |

| Scale 4: Embarrassment | |

| I leak stool without even knowing it | |

| I worry about others smelling stool on me | |

| I feel ashamed | |

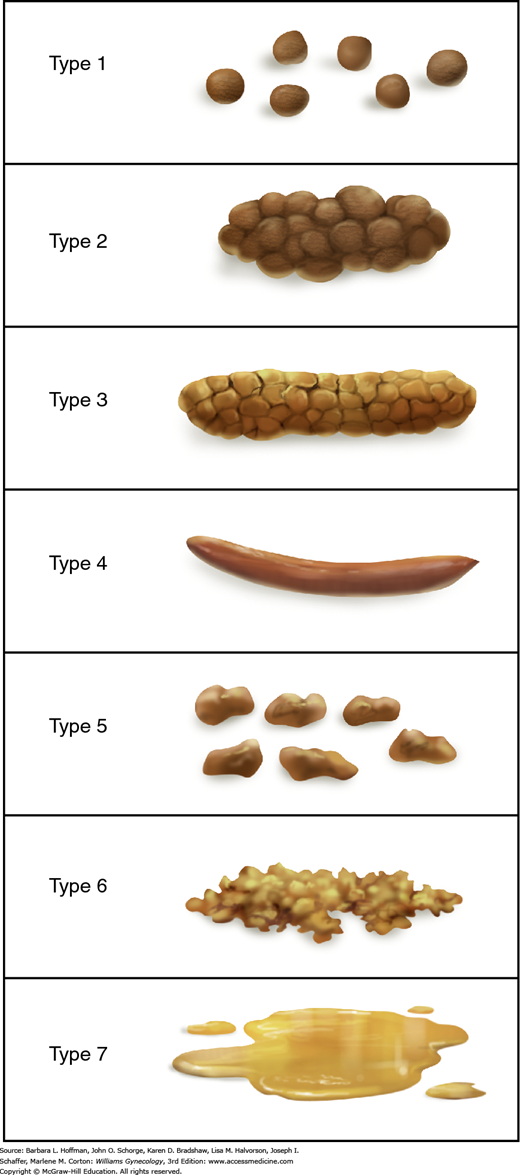

Last, the validated Bristol Stool Scale is often selected to determine a patient’s usual stool consistency (Lewis, 1997). This scale contains seven descriptions of stool characteristics and pictures of each stool type (Fig. 25-3) (Degen, 1996). Such stool consistency categorization correlates with objective measures of whole-gut transit time (Heaton, 1994).

This begins with careful inspection of the anus and perineum to identify stool soiling, scars, perineal body length, hemorrhoids, anal warts, rectal prolapse, dovetail sign, or other anatomic abnormalities (Fig. 25-4). The perianal skin is gently stroked with a cotton-tipped swab to obtain the cutaneous anal reflex. Colloquially termed anal wink, circumferential contraction of the anal skin and underlying EAS is normally seen. This finding provides gross assessment of pudendal nerve integrity.

FIGURE 25-4

Photograph showing the “dovetail” sign, which is created by disruption of the anterior portion of external anal sphincter (EAS). Radial skin spikes are typically formed by attachment of skin to the EAS but are commonly absent from 10 to 2 o’clock (asterisks) in those with this disruption.

With digital rectal examination, one can assess anal resting tone, sample for gross or occult blood, and palpate masses or fecal impaction. In addition, squeeze pressure can subjectively be judged during voluntary patient contraction of the EAS around a gloved finger inserted into the anorectum. Last, during patient Valsalva maneuver, one observes for excessive perineal body descent, vaginal wall prolapse, rectal prolapse, or muscle incoordination (Fig. 25-5). With the latter, a paradoxic contraction—that is, abnormal sphincter contraction around the finger—may be elicited during patient Valsalva when an examining finger is inserted into the anorectum. Digital rectal examination is reasonably accurate relative to manometry for assessing anal resting tone and squeeze function and for identifying dyssynergia (Orkin, 2010; Tantiphlachiva, 2010).

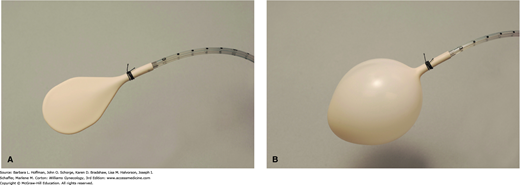

Physical and historical findings typically guide the remainder of testing, which may include imaging and functional studies. Of these, anorectal manometry is performed mainly in academic institutions with an anophysiology laboratory prior to surgical intervention. It is a functional test that allows objective assessment of: (1) rectal compliance and rectal sensation, (2) reflexes, and (3) anal sphincter function (Table 25-5). During this test, a small flexible tube containing an inflatable balloon tip and pressure transducer is inserted into the rectum (Fig. 25-6). First, rectal compliance and sensation may be determined by sequentially inflating a rectal balloon to various volumes. Decreased rectal compliance may be noted by an inability to inflate a balloon to typical volumes without patient discomfort. This may indicate a rectal reservoir that is unable to appropriately store stool. In contrast, decreased perception of balloon insufflation may indicate neuropathy.

| Manometry | ||||||||

| Factors | Resting | Squeeze | RP | RC | DG | EAUS | MRI | EMG |

| Muscle | ||||||||

| IAS | + | + | + | |||||

| EAS | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Puborectalis | + | + | + | |||||

| Rectum | ||||||||

| Perception | + | |||||||

| Compliance | + | |||||||

| Reservoir | + | + | + | |||||

| Megarectum | + | + | + | |||||

| Pelvic floor | ||||||||

| Perineal descent | + | + | ||||||

| Anorectal angle | + | + | ||||||

| Neural | ||||||||

| Pudendal nerve | + | + | ||||||

Second, sphincter reflexes are also assessed during pressure measurements. During balloon insufflation, relaxation of the IAS should accompany rectal distention via the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (p. 563).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree