INTRODUCTION

Serving as both specialist and primary care provider, a gynecologist has an opportunity to diagnose and treat a wide variety of diseases. Once problems are identified, clinicians, in consultation with the patient, determine how best to manage chronic medical issues based on their experience, practice patterns, and professional interests. Although some conditions may require referral, gynecologists play an essential role in patient screening, in emphasizing ideal health behaviors, and in facilitating appropriate consultation for care beyond their scope of practice.

Various organizations provide preventive care recommendations and update these regularly. Commonly accessed guidelines are those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and American Cancer Society.

MEDICAL HISTORY

During a comprehensive well-woman visit, patients are first queried regarding new or ongoing illness. To assist with evaluation, complete medical, social, and surgical histories are obtained and include obstetric and gynecologic events. Gynecologic topics usually cover current and prior contraceptives; results from prior sexually transmitted disease (STD) testing, cervical cancer screening, or other gynecologic tests; sexual history, described in Chapter 3; and menstrual history, outlined in Chapter 8. Obstetric questions chronicle circumstances around deliveries, losses, or complications. Current medication lists include both prescription and over-the-counter drugs and herbal agents. Also, prior surgeries, their indications, and complications are sought. A social history covers smoking and drug or alcohol abuse. Screening for intimate partner violence or depression can be completed, as outlined on page 18 and more fully in Chapter 13. Discussion might also assess the patient’s support system and any cultural or spiritual beliefs that might affect her general health care. A family history helps identify women at risk for familial or multifactorial disease such as diabetes or heart disease. In families with prominent breast, ovarian, or colon cancer, genetic evaluation may be indicated, and criteria are outlined in Chapters 33 and 35. Moreover, a significant family clustering of thromboembolic events may warrant testing, as describe in Chapter 39, especially prior to surgery or hormone initiation. Last, a review of systems, whether performed by the clinician or office staff, may add clarity to new patient problems.

For adults, following historical inventory, a complete physical examination is completed. Many women present to their gynecologist with complaints specific to the breast or pelvis. Accordingly, these are often areas of increased focus, and their evaluation is described next.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Self breast examination (SBE) is an examination performed by the patient herself to detect abnormalities. However, studies have shown that SBE increases diagnostic testing rates for ultimately benign breast disease and is ineffective in lowering breast cancer mortality rates (Kösters, 2008; Thomas, 2002). Accordingly, several organizations have removed SBE from their recommended screening practices (National Cancer Institute, 2015; Smith, 2015; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2009). That said, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2014b) and the American Cancer Society (2014) recommend breast self-awareness as another method of patient self-screening. Self-awareness focuses on breast appearance and architecture and may include SBE. Women are encouraged to report any perceived breast changes for further evaluation.

In contrast, clinical breast examination (CBE) is completed by a clinical health-care professional and may identify a small portion of breast malignancies not detected with mammography. Additionally, CBE may identify cancer in young women, who are not typical candidates for mammography (McDonald, 2004). One method includes visual inspection combined with axillary and breast palpation, which is outlined in the following section.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2014b) recommends that women receive a CBE every 1 to 3 years between ages 20 and 39. At age 40, CBE is completed annually. That said, the USPSTF (2009) and the American Cancer Society report insufficient evidence to recommend routine CBE (Oeffinger, 2015).

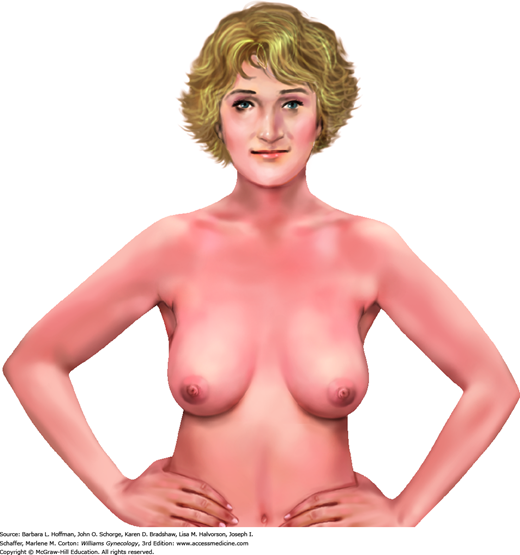

Initially during CBE, the breasts are viewed as a woman sits on the table’s edge with hands placed at her hips and with pectoralis muscles flexed (Fig. 1-1). Alone, this position enhances asymmetry. Additional arm positions, such as placing arms above the head, do not add vital information. Breast skin is inspected for breast erythema; retraction; scaling, especially over the nipple; and edema, which is termed peau d’orange change. The breast and axilla are also observed for contour symmetry.

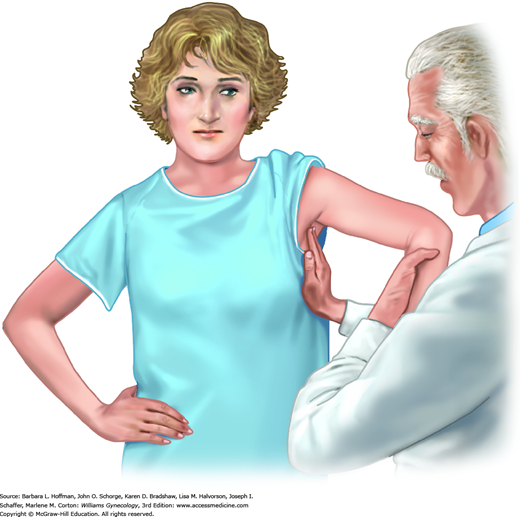

Following inspection, axillary, supraclavicular, and infraclavicular lymph nodes are palpated most easily with a woman seated and her arm supported by the examiner (Fig. 1-2). The axilla is bounded by the pectoralis major muscle ventrally and the latissimus dorsi muscle dorsally. Lymph nodes are detected as the examiner’s hand glides from high to low in the axilla and momentarily compresses nodes against the lateral chest wall. In a thin patient, one or more normal, mobile lymph nodes less than 1 cm in diameter may commonly be appreciated. The first lymph node to become involved with breast cancer metastasis (the sentinel node) is nearly always located just behind the midportion of the pectoralis major muscle belly.

FIGURE 1-2

One method of axillary lymph node palpation. Finger tips extend to the axillary apex and compress tissue against the chest wall in the rolling fashion shown in Figure 1-4. The patient’s arm is supported by the examiner.

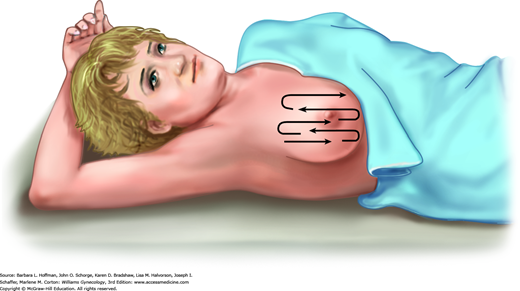

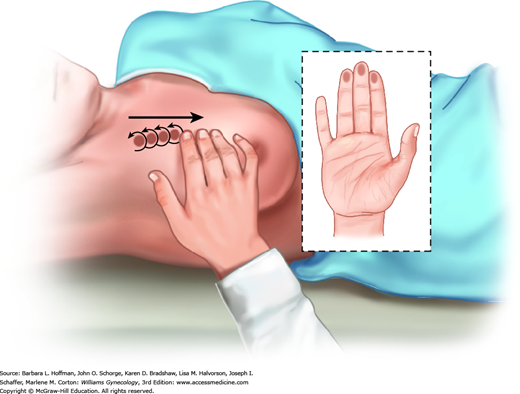

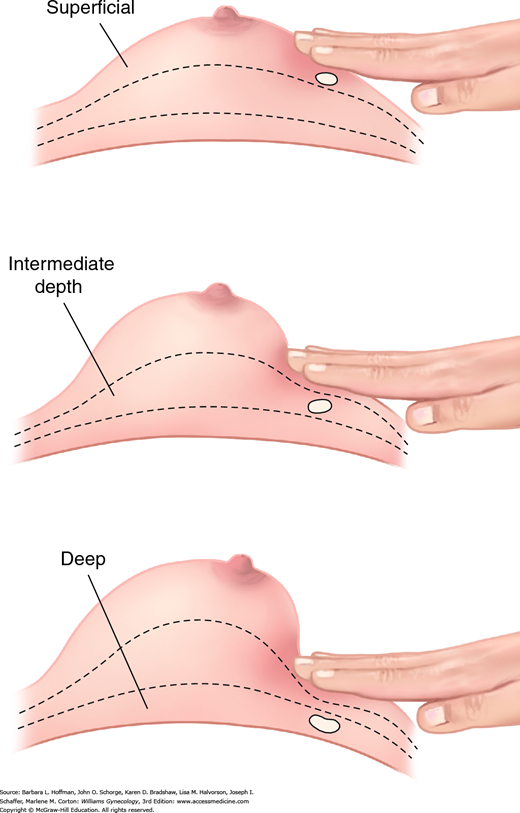

After inspection, breast palpation is completed with a woman supine and with one hand above her head to stretch breast tissue across the chest wall (Fig. 1-3). Examination includes breast tissue bounded by the clavicle, sternal border, inframammary crease, and midaxillary line. Breast palpation within this pentagonal area is approached in a linear fashion. Technique uses the finger pads in a continuous rolling, gliding circular motion (Fig. 1-4). At each palpation point, tissues is assessed both superficially and deeply (Fig. 1-5). During CBE, intentional attempts at nipple discharge expression are not required unless a spontaneous discharge has been described by the patient.

If abnormal breast findings are noted, they are described by their location in the right or left breast, clock position, distance from the areola, and size. Evaluation and treatment of breast and nipple diseases are described more fully in Chapter 12.

During examination, patients are educated that new axillary or breast masses, noncyclic breast pain, spontaneous nipple discharge, new nipple inversion, and breast skin changes such as dimpling, scaling, ulceration, edema, or erythema should prompt evaluation. This constitutes breast self-awareness. Patients who desire to perform SBE are counseled on its benefits, limitations, and potential harms and instructed to complete SBE the week after menses.

This examination is typically performed with a patient supine, legs in dorsal lithotomy position, and feet resting in stirrups. The head of the bed is elevated 30 degrees to relax abdominal wall muscles for bimanual examination. A woman is assured that she may stop or pause the examination at any time. Moreover, each part of the evaluation is announced or described before its performance.

Pelvic cancers and infections may drain to the inguinal lymph nodes, and these are palpated during examination. Following this, a methodical inspection of the perineum extends from the mons ventrally, to the genitocrural folds laterally, and to the anus. Notably, infections and neoplasms that involve the vulva can also involve perianal skin. Some clinicians additionally palpate for Bartholin and paraurethral gland pathology. However, in most cases, patient symptoms and asymmetry in these areas will dictate the need for this specific evaluation.

Both metal and plastic specula are available for this examination, each in various sizes to accommodate vaginal length and laxity. The plastic speculum may be equipped with a small light that provides illumination, whereas metal specula require an external light source. Preference between these two types is provider dependent. The vagina and cervix are typically viewed after placement of either a Graves or Pederson speculum (Fig. 1-6). Prior to insertion, a speculum may be warmed with running water or by warming lights built into some examination tables. Additionally, lubrication may add comfort to insertion. Griffith and colleagues (2005) found that gel lubricants did not increase unsatisfactory Pap smear cytology rates or decrease Chlamydia trachomatis detection rates compared with water lubrication. If gel lubrication is used, a dime-sized aliquot is applied sparingly to the outer surface of the speculum blades.

FIGURE 1-6

Vaginal specula. A. Pediatric Pederson speculum. This may be selected for child, adolescent, or virginal adult examination. B. Graves speculum. This may be selected for examination of parous women with relaxed and collapsing vaginal walls. C. Pederson speculum. This may be selected for sexually active women with adequate vaginal wall tone. (Used with permission from US Surgitech, Inc.)

Immediately before insertion, the labia minora are gently separated, and the urethra is identified. Because of urethral sensitivity, the speculum is inserted well below the meatus. Alternatively, prior to speculum placement, an index finger may be placed in the vagina, and pressure placed posteriorly against the bulbospongiosus muscle. A woman is then encouraged to relax this posterior wall to improve comfort with speculum insertion. This practice may prove especially helpful for women undergoing their first examination and for those with infrequent coitus, dyspareunia, or heightened anxiety.

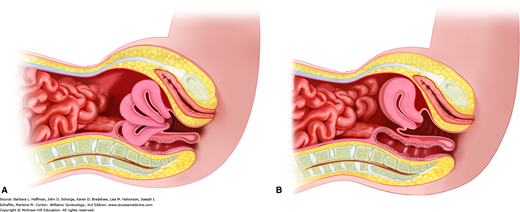

With speculum insertion, the vagina commonly contracts, and a woman may note pressure or discomfort. A pause at this point typically is followed by vaginal muscle relaxation. As the speculum bill is completely inserted, it is angled approximately 30 degrees downward to reach the cervix. Commonly, the uterus is anteverted, and the ectocervix lies against the posterior vaginal wall (Fig. 1-7).

As the speculum is opened, the ectocervix can be identified. Vaginal walls and cervix are inspected for masses, ulceration, or unusual discharge. As outlined in Chapter 29, cervical cancer screening is often completed, and additional swabs for culture or microscopic evaluation can also be collected. Screening for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis and other STDs is listed in Table 1-1.

| Infectious Agent | Screening Recommendations | Risk Factors |

| Chlamydia trachomatis + Neisseria gonorrhoeae | All <25 yr: annually Those older with risk factors: annually | New or multiple partners; inconsistent condom use; sex work; current or prior STD |

| Treponema pallidum | Those with risk factors | Sex work; confinement in adult correction facility; MSM |

| HIV virus | All 13–64 yr: one timea Those with risk factors: periodically | Multiple partners; injection drug use; sex work; concurrent STD; MSM; at-risk partners; initial TB diagnosis |

| Hepatitis C virus | All born from 1945 to 1965: one time Those with risk factors: periodically | Injection/intranasal drug use; dialysis; infected mother; blood products before 1992; unregulated tattoo; high-risk sexual behavior |

| Hepatitis B virus | Those with risk factors | HIV-positive; injection drug use; affected family or partner; MSM; multiple partners; originate from high-prevalence country |

| HSV | No routine screening |

Most often, the bimanual examination is performed after the speculum evaluation. Some clinicians prefer to complete the bimanual portion first to better identify cervical location prior to speculum insertion. Either process is appropriate. Uterine and adnexal size, mobility, and tenderness can be assessed during bimanual examination. For women with prior hysterectomy and adnexectomy, bimanual examination is still valuable and can be used to exclude other pelvic pathology.

During this examination, a gloved index and middle finger are inserted together into the vagina until the cervix is reached. For cases of latex allergy, nonlatex gloves are available. To ease insertion, a water-based lubricant can be initially applied to these gloved fingers. Once the cervix is reached, uterine orientation can be quickly assessed by sweeping the index finger inward along the ventral surface of the cervix. In those with an anteverted position, the uterine isthmus is noted to sweep upward, whereas in those with a retroverted position, a soft bladder is palpated. However, in those with a retroverted uterus, if a finger is swept along the cervix’s dorsal aspect, the isthmus is felt to sweep downward. With a retroverted uterus, this same finger is continued posteriorly to the fundus and then side-to-side to assess uterine size and tenderness.

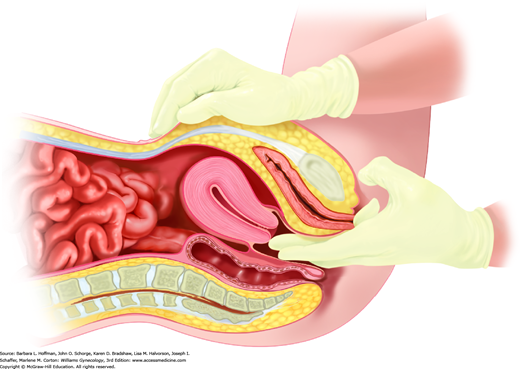

To determine the size of an anteverted uterus, fingers are placed beneath the cervix, and upward pressure tilts the fundus toward the anterior abdominal wall. A clinician’s opposite hand is placed against the abdominal wall to locate the upward fundal pressure (Fig. 1-8).

To assess adnexa, the clinician uses two vaginal fingers to lift the adnexa from the cul-de-sac or from Waldeyer fossa toward the anterior abdominal wall. The adnexa is trapped between these vaginal fingers and the clinician’s other hand, which is exerting downward pressure against the lower abdomen. For those with a normal-sized uterus, this abdominal hand is typically best placed just above the inguinal ligament.

The decision to perform rectovaginal evaluation varies among providers. Some prefer to complete this evaluation on all adults, whereas others elect to perform rectovaginal examination for those with specific indications. These may include pelvic pain, an identified pelvic mass, rectal symptoms, or risks for colon cancer.

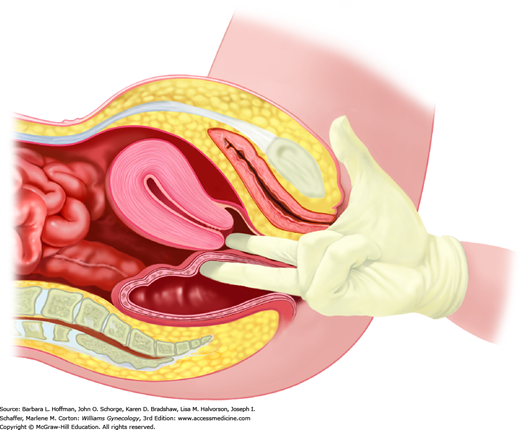

Gloves are changed between bimanual and rectovaginal examinations to avoid contamination of the rectum with potential vaginal pathogens. Similarly, if fecal occult blood testing is to be done at this time, the glove is changed after bimanual examination to minimize false-positive results. Initially, an index finger is placed into the vagina and a middle finger into the rectum (Fig. 1-9). These fingers are swept against one another in a scissoring fashion to assess the rectovaginal septum for scarring or peritoneal studding. The index finger is removed, and the middle finger completes a circular sweep of the rectal vault to exclude masses. If immediate fecal occult blood testing is indicated, it may be performed with a sample from this portion of the examination. As noted later, this single fecal occult blood testing does not constitute adequate colorectal cancer screening.

Periodic health evaluation and screening can prevent or detect numerous medical conditions. Moreover, periodic visits also foster a patient-physician partnership to help guide a woman through adolescence, reproductive years, and past menopause.

An initial reproductive health visit is recommended between ages 13 and 15 years (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2014e). This visit initiates a discussion between an adolescent and health-care provider on issues of general reproductive health, puberty, menstruation, contraception, and STD protection. Although not mandated, a pelvic examination may be necessary if gynecologic symptoms are described. Adolescents may prefer to include parents in their gynecologic health care. However, as discussed in Chapter 14, adolescents may seek care for STDs, substance abuse, contraception, or pregnancy without parental permission (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2014a).

For women older than 21 years, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2014f) recommends annual well woman visits, during which physical and pelvic examinations are completed. Pelvic evaluation contains those components listed on page 4, namely, inspection and speculum, bimanual, and rectal examinations. However, evidence neither supports nor refutes the value of annual pelvic evaluation in asymptomatic women. Thus, exclusion of this portion is a shared decision following patient-provider discussion. Women with gynecologic complaints are encouraged to permit this examination.

One topic in this conversation is cervical cancer screening. For many women, the appropriate screening interval may not be annually, and specific screening methods and schedules are discussed in Chapter 29. Second, in the past, endocervical swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia infection screening during speculum examination were preferred. Now, such screening can be completed with similar accuracy using nucleic acid amplification testing of urine, vaginal, or endocervical samples.

Other professional organizations have also published statements regarding preventive care visits. The Institute of Medicine (2011) recommends at least one annual well woman visit to obtain preventive services, including preconception and prenatal care. However, investigators from the American College of Physicians (ACP) reviewed pelvic examination benefits and harms in asymptomatic adult women (Qaseem, 2014). These authors describe scarce data to determine the ideal interval for routine pelvic examination. Accordingly, the ACP recommends against screening pelvic examination for asymptomatic, nonpregnant adult women. Thus, again, with each annual visit, a discussion of benefits and risks and an agreement to examination is prudent.

PREVENTIVE CARE

Gynecologists have an opportunity to evaluate their patients for leading causes of female morbidity and mortality and intervene accordingly. Thus, familiarity with various screening guidelines is essential. In 2014, recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2014f) were updated. The USPSTF (2014) regularly revises its screening guidelines, which can be accessed at www.USPreventiveServicesTaskForce.org. These, along with other specialty-specific recommendations, offer valuable guidance for clinicians providing preventive care. Many of these topics are covered in other text chapters. Some remaining important subjects are present in the following sections.

The need for new or repeat administration of vaccines should be reviewed periodically. Some vaccines are recommended for all adults, whereas others are indicated because of patient comorbidities or occupational exposure risks. For most healthy adults who have completed the indicated childhood and adolescent immunization schedules, those that warrant consideration are listed in Table 1-2. This table summarizes recommended schedules, precautions, and contraindications for these adult vaccines. As of 2015, a link is provided to the full schedules at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/.

| Vaccine and Route | Reason to Vaccinate | Vaccine Administration | Contraindications and Precautionsa,b |

| Influenza |

|

| Precaution

|

| Pneumococcal PCV13 PPSV23 Give IM or SC |

|

| |

| Hepatitis B Give IM |

|

| |

| Hepatitis A Give IM |

|

| |

| Td Tdap Give IM |

|

| Contraindication

Precaution

|

| Varicella Give SC |

|

| Contraindications

Precaution

|

| Zoster Give SC |

|

| Contraindications

Precaution

|

| Meningococcal MCV4 Give IM MPSV4 Give SC |

|

| |

| MMR Give SC |

|

| Contraindications

Precaution

|

| HPV Give IM |

|

| Precaution

|

In general, any vaccine may be coadministered with another type at the same visit. Notably, the influenza vaccine is available in several formulations. Vaccines for human papillomavirus infection prevention, Gardasil and Cervarix, are discussed additionally in Chapter 29.

In the United States, nearly 64,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are predicted, and this malignancy is the third leading cause of cancer death in women, behind lung and breast cancer (Siegel, 2015). Incidence and mortality rates from this cancer have declined during the past two decades, largely due to improved screening tools. However, adherence to colorectal cancer screening guidelines for women is usually less than 50 percent (Meissner, 2006).

Guidelines recommend screening average-risk patients for colorectal cancer beginning at age 50 with any of the methods shown in Table 1-3 (Smith, 2015). Screening is selected from either of two method categories. The first is capable of identifying both cancer and precancerous lesions. The second group of methods primarily detects only cancer and includes the fecal occult blood test, fecal immunochemical test, and stool DNA tests.

| Tests That Detect Adenomatous Polyps and Cancera | ||

| Test | Interval | Key Issues for Informed Decisions |

| Colonoscopy | 10 years | Bowel prep required; conscious sedation provided |

| FSIG | 5 years | Bowel prep required, sedation usually not provided Positive findings usually merit colonoscopy |

| Barium enema (DCBE) | 5 years | Bowel prep required; polyps ≥6 mm merit colonoscopy |

| Colonography (CTC) | 5 years | Bowel prep required; polyps ≥6 mm merit colonoscopy |

Of these, colonoscopy is often the preferred test for colorectal cancer screening. For the patient with average risk and normal findings, testing is repeated in 10 years. In the United States, flexible sigmoidoscopy is used less frequently. Its limitations include that only the distal 40 cm of colon are seen, and if lesions are found, then colonoscopy is still needed. A final suitable option—computed tomographic (CT) colonography—is not often covered by insurance plans.

Fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) is an adequate annual screening method when two or three stool samples are self-collected by the patient, and the cards are returned for analysis. This method relies on a chemical oxidation reaction between the heme moiety of blood and alpha guaiaconic acid, a component of guaiac paper. Heme catalyzes the oxidation of alpha guaiaconic acid by hydrogen peroxide, the active component in the developer. This oxidation reaction yields a blue color (Sanford, 2009). Red meat, raw cauliflower, broccoli, members of the radish family, and melons have similar oxidizing ability and may yield false-positive results. Vitamin C may preemptively react with the reagents and lead to false-negative results. All of these are eliminated for 3 days before testing. Additionally, women should avoid nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 7 days prior to testing to limit risks of gastric irritation and bleeding. These restrictions are cumbersome for some patients and lead to noncompliance with recommended testing.

Alternatively, the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) relies on an immune reaction to human hemoglobin. Similar to FOBT, the FIT test is performed for annual screening on two or three patient-collected stool samples and does not require pretesting dietary limitations. Advantages to FIT include greater specificity for human blood and thus fewer false-positive results from dietary meat and vegetables and fewer false-negative results due to vitamin C. As another option, screening may be completed with stool DNA (sDNA) testing. One FDA-approved test, Cologuard, screens stool for both DNA and hemoglobin biomarkers that are associated with colorectal cancer (Imperiale, 2014). Positive test results from any of these three warrant further evaluation by colonoscopy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree