Burn Management

Kathy N. Shaw

Marc H. Gorelick

Introduction

In 2002, there were more than 163,000 emergency department (ED) visits for burn injuries (1). Most of these burns occurred in the home, and the majority were preventable. Young children less than 4 years of age have the highest incidence of injury from burns. They are most at risk for scald burns requiring hospitalization and for death in house fires. Overall, burn injuries are the third leading cause of accidental death in children (2,3). Burns also are a significant mechanism of child abuse (4).

Four different types of burns may occur, depending on the source of injury. Thermal burns are the most common type of burn injury seen in children (2). They occur as a result of scalds, contact burns, or flame injuries. Chemical burns in children usually involve ingestion or contamination with acids or alkalis found in household products. Electrical burns are usually low-voltage injuries that occur in toddlers mouthing electrical cords or playing with sockets. Although rare, high-voltage injuries may be seen, typically in older children or adolescents. Radiation burns in children are usually due to sunburn (5).

Most burns are minor and can be treated in an outpatient setting. In order to make decisions regarding management, the physician must be able to determine the depth or degree of the burn, the percentage of body surface area involved, whether the pattern of injury is typical of abuse, and whether deformity or loss of function may occur. Once a burn is determined to be minor, trained nursing or emergency medical services (EMS) personnel can often provide local care. The care the minor burn patient receives is crucial to the ultimate outcome. Many of the same principles apply to burns as those discussed under basic wound care (Chapter 107). The goals are to relieve pain, prevent infection and additional trauma, and minimize scarring and contracture. Treatment of the major burn victim should be performed by physicians trained in burn management. The initial care of the major burn victim is critical to both immediate survival and the ultimate outcome (6,7). Expert pediatric respiratory management is often needed for major burn victims with smoke inhalation. Mortality for these children is much higher than for those children with comparable burns but no smoke inhalation (8).

Anatomy and Physiology

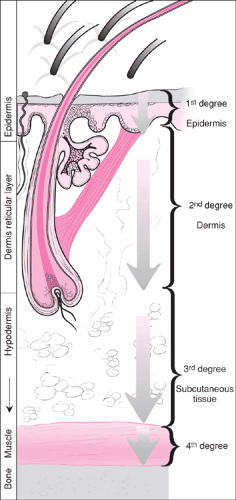

The skin is the largest organ in the body and has many important functions. It acts as a barrier to infection and loss of body water, as a thermal regulator, as a sensory organ, and as an excretory organ. Of the skin’s three layers (Fig. 113.1), the dermis contains the blood vessels, nerves, and epithelial appendages (e.g., hair) as well as sebaceous and sweat glands that are necessary for most of the skin’s primary functions and for self-repair. The depth of the burn injury therefore determines the extent of the damage to this organ and its ability to heal (Table 113.1). Superficial or first-degree burns affect only the epidermis or tough protective barrier. A mild sunburn is a typical example. Partial-thickness or second-degree burns extend into the dermis. Deep second-degree burns may mimic third-degree burns, as most of the skin elements are destroyed. Healing is prolonged, and hypertrophic scarring may occur. Full-thickness or third-degree burns involve the entire dermis, including neurovascular structures. Fourth-degree burns extend into the muscle, fascia, or bone.

Both the depth and degree of the burn and the extent of skin involvement determine the severity of the injury and affect the skin’s ability to maintain its physiologic functions. First-degree burns are not included in calculations of the extent of involvement unless the area exceeds 25% to 30% of the

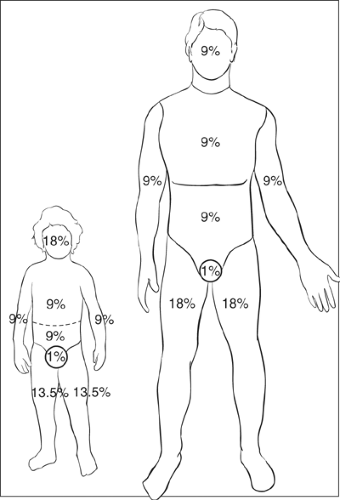

body surface area. Estimates of body surface area (BSA) involvement in babies and young children cannot be done using the “rule of 9s” because they have a proportionately larger head and smaller lower extremities (Fig. 113.2). Emergency departments should have access to tables listing BSA by body part and age of the child, such as the Lund and Browder charts (9). For smaller burns, the area can be estimated by comparing the child’s palm size, which is 1% of BSA, with the burned area.

body surface area. Estimates of body surface area (BSA) involvement in babies and young children cannot be done using the “rule of 9s” because they have a proportionately larger head and smaller lower extremities (Fig. 113.2). Emergency departments should have access to tables listing BSA by body part and age of the child, such as the Lund and Browder charts (9). For smaller burns, the area can be estimated by comparing the child’s palm size, which is 1% of BSA, with the burned area.

Indications

Treatment of burns depends on the severity of injury, location, characteristics of the child, and mechanism of injury (Table 113.2). A first-degree burn is identified by pain, erythema, and subsequent peeling, but healing occurs without scarring. A typical second-degree burn is painful, red, blanches with pressure, has weeping blisters, and usually heals with minimal or no scarring. Deep second-degree burns may appear white and be anesthetic but often will blanch with pressure. Third-degree burns are dry, leathery, white or charred in appearance, painless, and require grafting because the dermis has been destroyed. The depth of the burn sometimes can be difficult to determine in the first few hours and may require repeated examinations.

Minor burns are usually treated in the ED or office by trained personnel, including nurses and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) under the supervision of a physician. A minor burn is defined as a second-degree burn that covers less than 10% of BSA in children under 6 years of age and less than 15% in older children and adults or a third-degree burn that covers less than 2% of the BSA. Exceptions include burns that may cause loss of function or severe deformity or are associated with a higher risk of infection, such as burns of the hands, face, eyes, ears, feet, perineum, or genitalia. In addition, burns should not be classified as minor if the child has an underlying disease that may affect the healing process, if the burn is suspected to have occurred from child abuse or neglect, if the caretaker is unable to care for the burn, or if the burn is circumferential and may require escharotomy or crosses a flexion crease indicating a more severe injury.

Major burns include second-degree burns greater than 20% of BSA and third-degree burns greater than 10% of the BSA in children. In addition, burns associated with smoke inhalation or major trauma or high-voltage electrical burns should be considered major burns. When concern arises about the healing process, the clinician also should consider it a major burn. These should be treated by a physician knowledgeable in burn care. General or plastic surgeons should be consulted as needed and when available, especially for procedures such as escharotomy and treatment of burns that may cause disability or disfigurement. Most major burns require the special facilities and personnel of a burn center. Transfer to a center with pediatric intensive care should be considered for children with inhalational or high-voltage electrical injuries regardless of the extent of the burns. Most burns of moderate extent also require hospitalization or close follow-up by a physician knowledgeable in burn management.

Equipment

Standard resuscitation equipment, including airway equipment, supplemental oxygen, intravenous access, and isotonic intravenous fluids, such as lactated Ringer’s.

TABLE 113.1 Characteristics of Burns by Degree

Degree

Symptoms/physical examination

Healing

Causes

First (superficial)

Pain 48–72 hr

Erythema

Mild edema

Blanches

Epithelium may peel in 5–10 days

No scarring

Ultraviolet light

Second (partial thickness)

Superficial

Superficial

Superficial

Painful

10–14 days

Short flash

Bright red

Weeping Blisters

Minimal or no scarring

Brief scald

Deep

Deep

Deep

White/yellow or mottled

25–35 days

Scalds

+/- anesthetic

Hypertrophic scarring

Short flash

Third (Full thickness)

Dry, leathery

Anesthetic

Pearly white → charred

Thrombosed veins visible

Requires grafting

Flame

Scald

Electrical

A cardiorespiratory monitor and pulse oximeter also should be available.

Cleaning and débridement

Sterile saline or water

Syringes, 30 to 60 mL

Gauze pads

Povidone-iodine solution, one-quarter strength

Forceps

Scissors

Dressing

Sterile sheet (for major burns)

Tongue depressor (to apply topical agents)

Topical antimicrobial agent. The most commonly used is 1% silver sulfadiazine cream (Silvadene, Thermazene). This has the advantages of broad-spectrum activity, ease and comfort of application, and lack of absorption. Its use, however, is not recommended on the face (6). Other broad-spectrum preparations, such as bacitracin/polymyxin B (Polysporin), may be used for small burns, particularly those involving the face. Mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon) is another topical antimicrobial cream that is occasionally used but should be avoided in the outpatient setting due to the potential for serious systemic side effects (6).

Inner dressing. Inner dressings are generally divided into conventional and synthetic (10,11). Conventional dressings are those made from cotton gauze. The gauze may be plain or impregnated with a greasy material such as petrolatum to render it nonadherent; examples include Aquaphor, Vaseline, and Adaptic. Xeroform gauze also incorporates 3% bismuth tribromophenate as an antibacterial agent.

A wide variety of synthetic materials also are available. These have been designed to render frequent dressing changes unnecessary. Some dressings commonly available in the United States include semipermeable polyurethane films, such as OpSite and Tegaderm (adhesive) and Epi-Lock (nonadhesive); hydrocolloid

dressings, such as DuoDerm; and composites, including Biobrane and Epigard.

TABLE 113.2 Classification of Burns in Children

Classification

Burn

Associated factors

Disposition

Major

2°: >20% BSA

Potential loss of function

Burn center

3°: >10% BSA

or

Increased risk of infection

Circumferential

Severe deformity

Crosses flexion crease

e.g., burns of hands, face, ears, nose, feet, perineum, genitalia

e.g., immunosuppressed child

High-voltage injury

Pediatric intensive care

or

Smoke inhalation

Moderate

2°: 10% to 20%

+

None of above

Hospitalization or close follow-up by specialist

3°: 2% to 20%

or

or

Parental inability to care for burn

Child abuse suspected

Minor

2°: <10% BSA

3°: <2% BSA

+

None of above

Outpatient treatment

A number of investigators have failed to demonstrate the clear superiority of any of the various types of dressings—all provide satisfactory results when properly used (12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19). Conventional dressings continue to be the most widely used and have the advantages of being readily available and simple to apply. Moreover, most health care providers are familiar with their use. Synthetic dressings, by obviating the need for frequent dressing changes, may make home care easier and may minimize patient discomfort. Several studies comparing different dressings have found total costs to be similar (12,16). Thus, the choice of dressing method is largely a matter of patient and physician preference.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree