Bladder Catheterization

Suzanne Beno

Sandra Schwab

Introduction

Bladder catheterization is performed to obtain urine in a sterile manner for culture and urinalysis (1). The procedure allows for relatively easy and timely access to urine, particularly in the young child who cannot void on command. A bladder catheter also may be placed for monitoring urine output and relieving obstruction. Some obvious psychosocial issues impact on children of all age groups (and parents) regarding exposed genitalia and perceived violation of this sensitive area. Some cultural groups may even fear that a daughter’s virginity will be compromised by urinary catheterization (2). All patients and/or parents thus deserve a brief but careful explanation of the relevant anatomy and details of the procedure. Respect for modesty and privacy is critical and will be highly appreciated by the older child and all parents.

Anatomy and Physiology

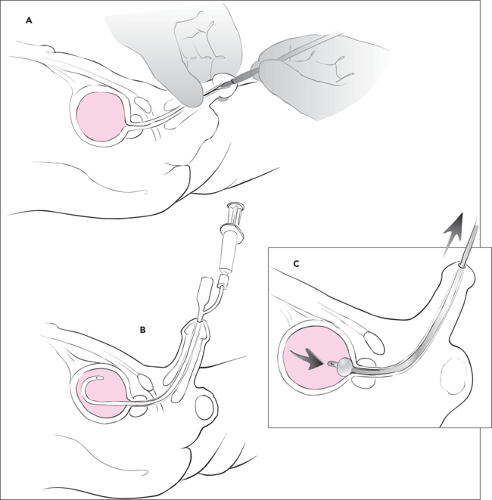

The relevant anatomy of the prepubertal child is generally similar to that of the adult, except for the obvious differences in size and lack of secondary sexual characteristics. In boys, the urethral meatus is usually easy to locate, but the long course of the urethra and its relative fixation at the level of the symphysis pubis can make passage of the catheter difficult (3). Holding the penis straight with slight traction at 90 degrees vertical to the abdominal wall straightens the urethral course and facilitates catheter passage (Fig. 95.1).

In the uncircumcised neonate or infant boy, a tight foreskin can make the task of locating the urethral meatus challenging. Usually gentle retraction of the foreskin will expose enough of the glans to visualize the meatus. Infant males with hypospadias may require more exploration on the ventral surface of the shaft to identify the urethral meatus. Some infant boys with chronic ammoniacal diaper dermatitis may acquire meatal stenosis and thus require a smaller catheter than might otherwise be typical for their age. Whereas difficult catheterization in the adult male may result from prostatic hypertrophy, urethral obstruction in a young boy may indicate the presence of post-traumatic urethral stricture or congenital anomalies.

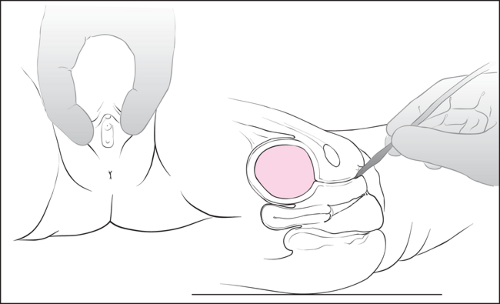

In the young female child, the urethra is short and generally easy to catheterize once the orifice is visualized. However, the opening is in close proximity to the vaginal introitus, and the mucosa of the introitus may cover the urethral meatus, making it difficult to locate (Fig. 95.2) (4). It may be noted that gentle lateral traction of the labia and gentle downward pressure on the cephalad aspect of the vaginal introital fold with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator allows visualization of the infantile female urethral meatus more readily (Fig. 95.3) (4). Alternatively, gently grasping the labia between thumb and forefinger and applying gentle lateral and outward traction (toward the clinician) may expose the urethral meatus (Fig. 95.4). Two additional considerations may complicate urethral visualization in girls. Female hypospadias results when the meatus opens into the distal anterior wall of the vagina. A catheter with a curved tip (coudé) may allow catheterization, usually just inside the introitus on the roof of the vagina. Additionally, labial adhesions may be present in infant girls. In this context, another technique, such as suprapubic aspiration, is generally preferred for simple collection of urine.

Indications

The most common indication for catheterizing a young child in the ED or ambulatory setting is the need to obtain a sterile urine specimen for laboratory analysis with culture and sensitivity (1). In infants and small children with suspected urinary tract infection, no localizing signs of fever, or possible sepsis,

a sterile urine specimen is paramount to reaching a diagnosis. Commonly, either bladder catheterization or suprapubic aspiration is used. The latter procedure is considered by many authorities to be the gold standard for obtaining bacteriologically uncontaminated specimens; however, it is frequently unsuccessful with small bladder volumes of urine, which are common in ill or dehydrated infants (1). Other common indications for catheterization include preventing or relieving urinary retention and close monitoring of urine output for fluid balance with an indwelling urinary catheter in the critically ill or injured child. Catheterization is also indicated on occasion in situations in which (a) urgent cystourethrography needs to be performed, (b) a child is suffering from contusions or burns (scald, flame, or chemical) to the perineum and thus at risk for meatal swelling and obstruction to urine outflow, (c) a temporizing measure is required to relieve lower

urinary tract obstruction (e.g., in a male neonate with posterior urethral valves), (d) a child has a neurogenic bladder due to spinal dysfunction as a result of trauma or congenital anomalies such as spina bifida, and (e) general anesthesia–induced and/or surgery-induced urinary retention has occurred.

a sterile urine specimen is paramount to reaching a diagnosis. Commonly, either bladder catheterization or suprapubic aspiration is used. The latter procedure is considered by many authorities to be the gold standard for obtaining bacteriologically uncontaminated specimens; however, it is frequently unsuccessful with small bladder volumes of urine, which are common in ill or dehydrated infants (1). Other common indications for catheterization include preventing or relieving urinary retention and close monitoring of urine output for fluid balance with an indwelling urinary catheter in the critically ill or injured child. Catheterization is also indicated on occasion in situations in which (a) urgent cystourethrography needs to be performed, (b) a child is suffering from contusions or burns (scald, flame, or chemical) to the perineum and thus at risk for meatal swelling and obstruction to urine outflow, (c) a temporizing measure is required to relieve lower

urinary tract obstruction (e.g., in a male neonate with posterior urethral valves), (d) a child has a neurogenic bladder due to spinal dysfunction as a result of trauma or congenital anomalies such as spina bifida, and (e) general anesthesia–induced and/or surgery-induced urinary retention has occurred.

Figure 95.2 With girls, the urethra is short and generally easily catheterized with adequate visualization of the urethral meatus. |

Determining whether bladder catheterization is contraindicated begins with a careful consideration of whether less invasive methods would suffice in a given clinical context (3). Voided urine may be sufficient to use for urinalysis in some circumstances (e.g., detection of hematuria, glycosuria, specific gravity) and is certainly adequate for establishing gross patency and function of the urinary system. Many children aged 2 years and older are able to provide a voided specimen, and if only urinalysis is needed, clean catch specimens are usually adequate. Documentation of physiologic urine production (e.g., after intravenous hydration) can be accomplished in many patients by simply placing an adherent plastic urine bag on the child after adequately prepping the perineum. In the dehydrated child, invasive methods of obtaining urine should be postponed for 60 to 90 minutes after initiating intravenous hydration to allow for some bladder filling. Otherwise, a highly concentrated few milliliters of “sludge” will be obtained, rendering a urinalysis difficult to interpret and often necessitating a subsequent attempt at catheterization.

The primary absolute contraindication to placement of a catheter is trauma with possible urethral injury, such as a pelvic fracture (5). Urethral injury is typically suspected if the findings include blood at the urethral meatus, displaced or high-riding prostate gland on rectal examination, or perineal hematoma. Careful consideration should also be given to patients with recent genitourinary surgery. Consultation with an urologist is recommended prior to placing a catheter in any of these situations.