● AORTIC STENOSIS

Definition, Spectrum of Disease, and Incidence

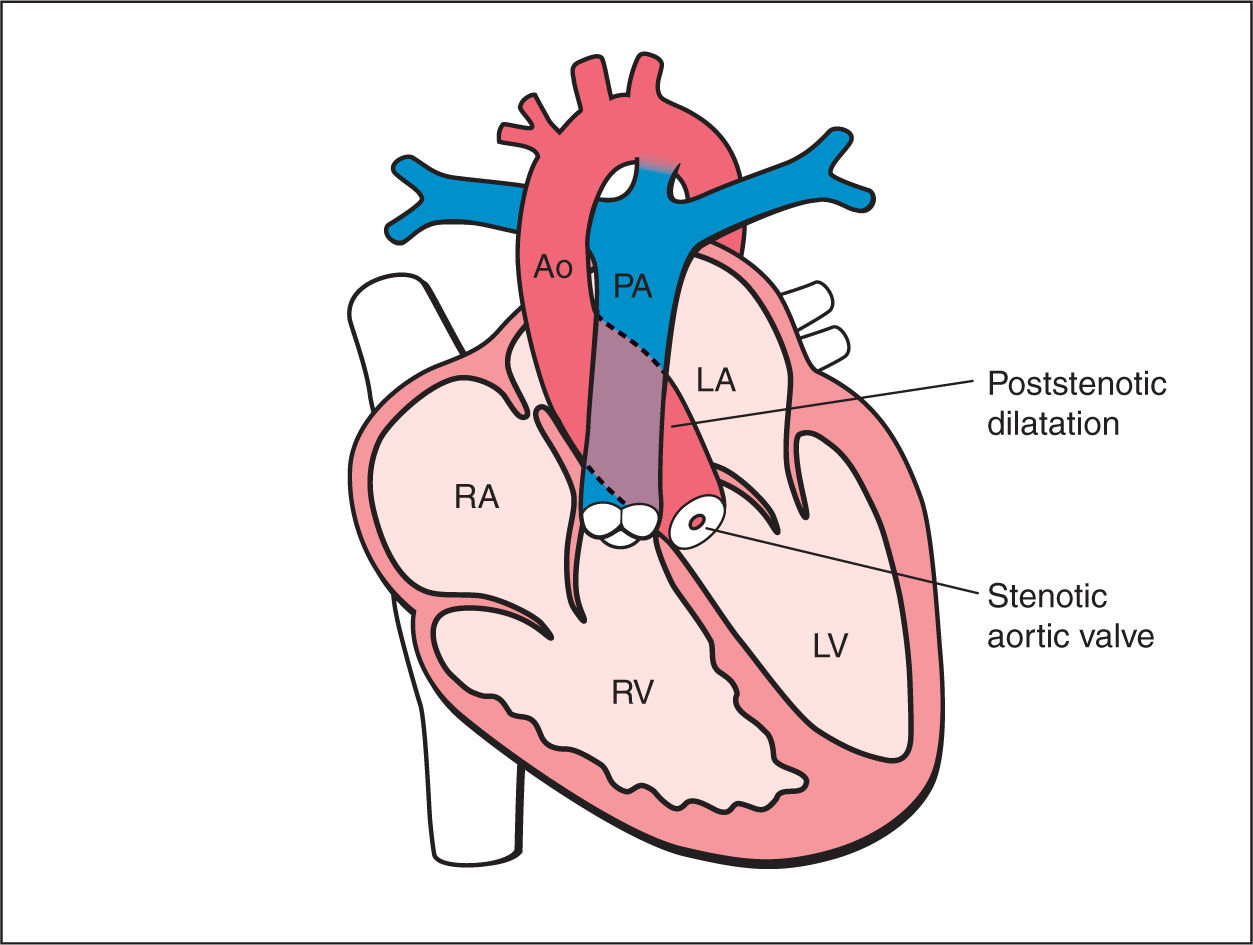

Aortic stenosis is defined as narrowing at the level of the aortic valve leading to an obstruction of left ventricular outflow (Fig. 21.1). The stenosis is classified as valvular, subvalvular, or supravalvular according to the anatomic location of the obstruction in relation to the aortic valve. Valvular aortic stenosis is the most common type diagnosed prenatally; the other two are rarely encountered on prenatal ultrasound, especially in an isolated form.

In valvular aortic stenosis, the valve leaflets are dysplastic and are either tricuspid with fused commissures, bicuspid, unicuspid, or noncommissural. The spectrum of aortic stenosis varies from an isolated mild lesion, mild aortic stenosis (Fig. 21.1), to a severe lesion, critical aortic stenosis, which may lead to a secondary dysfunction of the left ventricle with signs of endocardial fibroelastosis (see Fig. 22.2). The latter condition will be discussed together with the hypoplastic left heart syndrome in Chapter 22. Table 21.1 lists differentiating characteristics of mild versus critical aortic stenosis.

Aortic stenosis occurs in 3% to 6% of structural heart defects and is more common in boys, with a ratio of 3:1 to 5:1 (1–3). Isolated mild aortic stenosis is rare in fetal series (4). Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is a very common condition and is discussed later in this chapter. The prenatal diagnosis of BAV is uncommon (5).

Figure 21.1: Schematic drawing of valvular aortic stenosis. Note the narrowing at the level of the stenotic aortic valve and the poststenotic dilatation. The left ventricle (LV) appears normal. RV, right ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; PA, pulmonary artery; Ao, aorta.

Differentiating Characteristics of Mild and Critical Aortic Stenosis |

Mild aortic stenosis | Critical aortic stenosis | |

Aortic valve | Thickened | Thickened |

Systolic aortic flow | Antegrade turbulent | Antegrade turbulent |

LV size | Normal | Dilated |

LV contractility | Normal | Reduced |

LV wall echogenicity | Normal | Hyperechogenic (fibroelastosis) |

Mitral flow | Antegrade | Short diastole and mitral regurgitation |

Aortic isthmus flow | Antegrade flow | Partially reverse flow |

Foramen ovale | Right-to-left shunt | Left-to-right shunt when mitral regurgitation |

LV, left ventricle.

Ultrasound Findings

Gray Scale

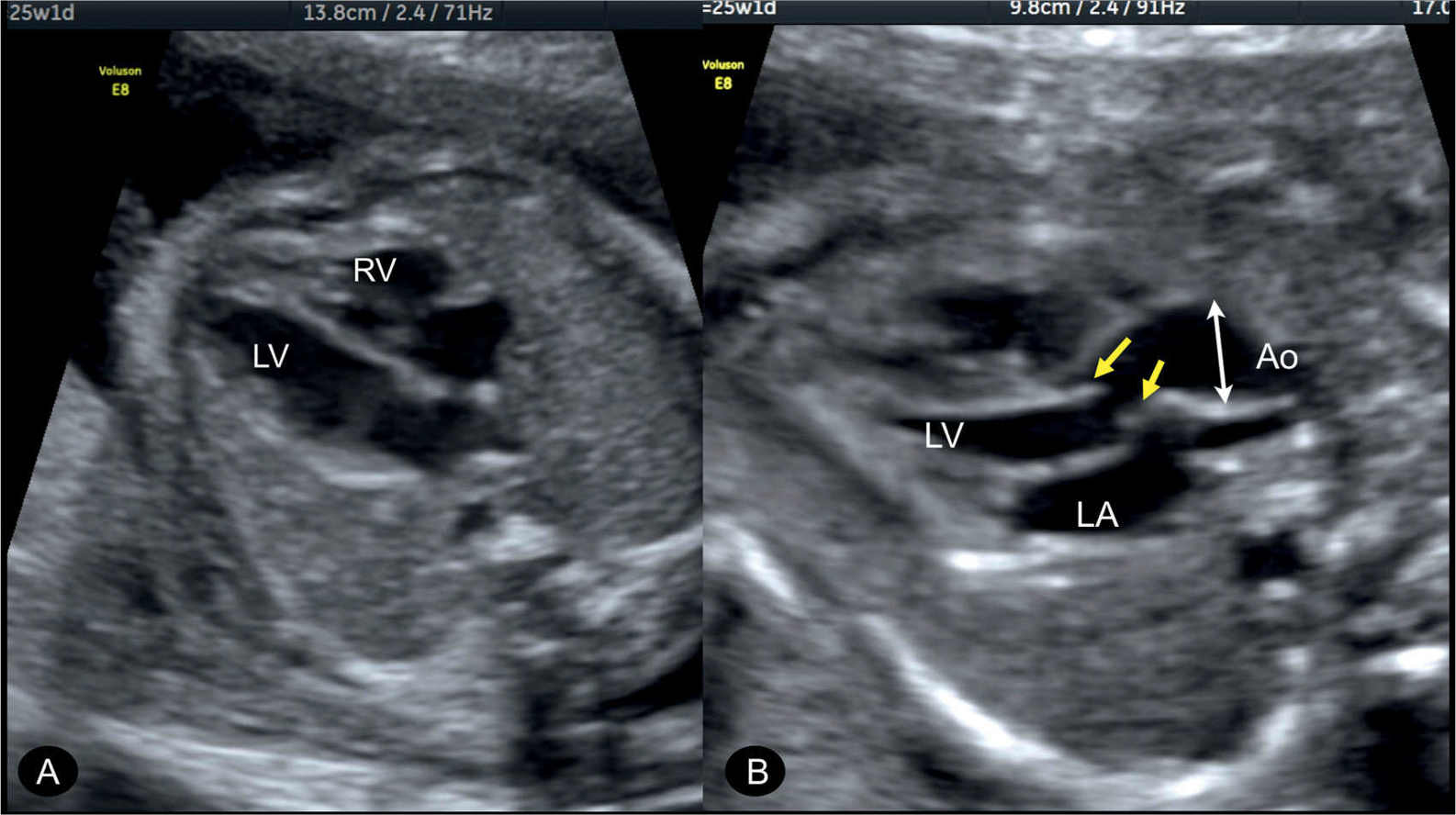

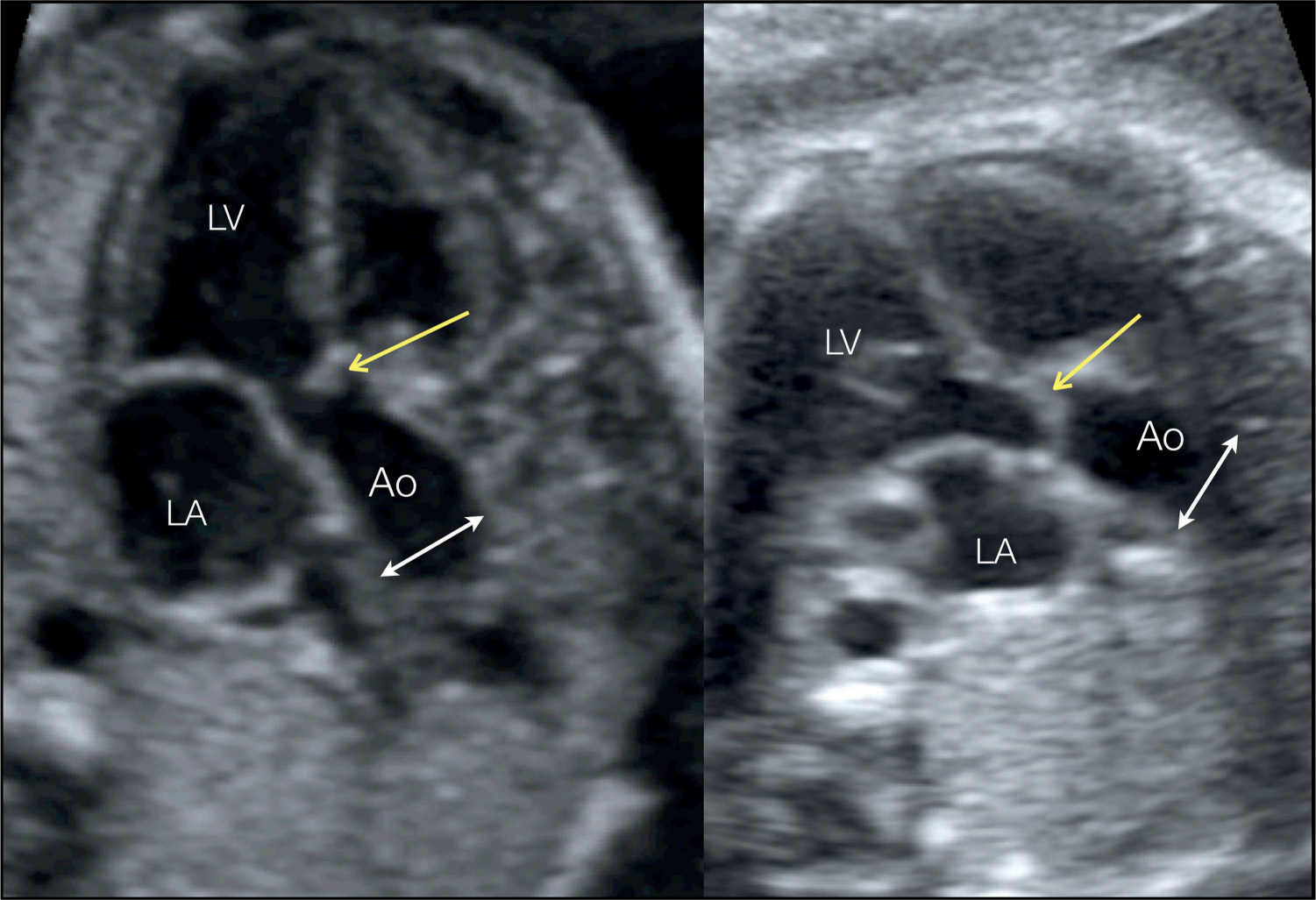

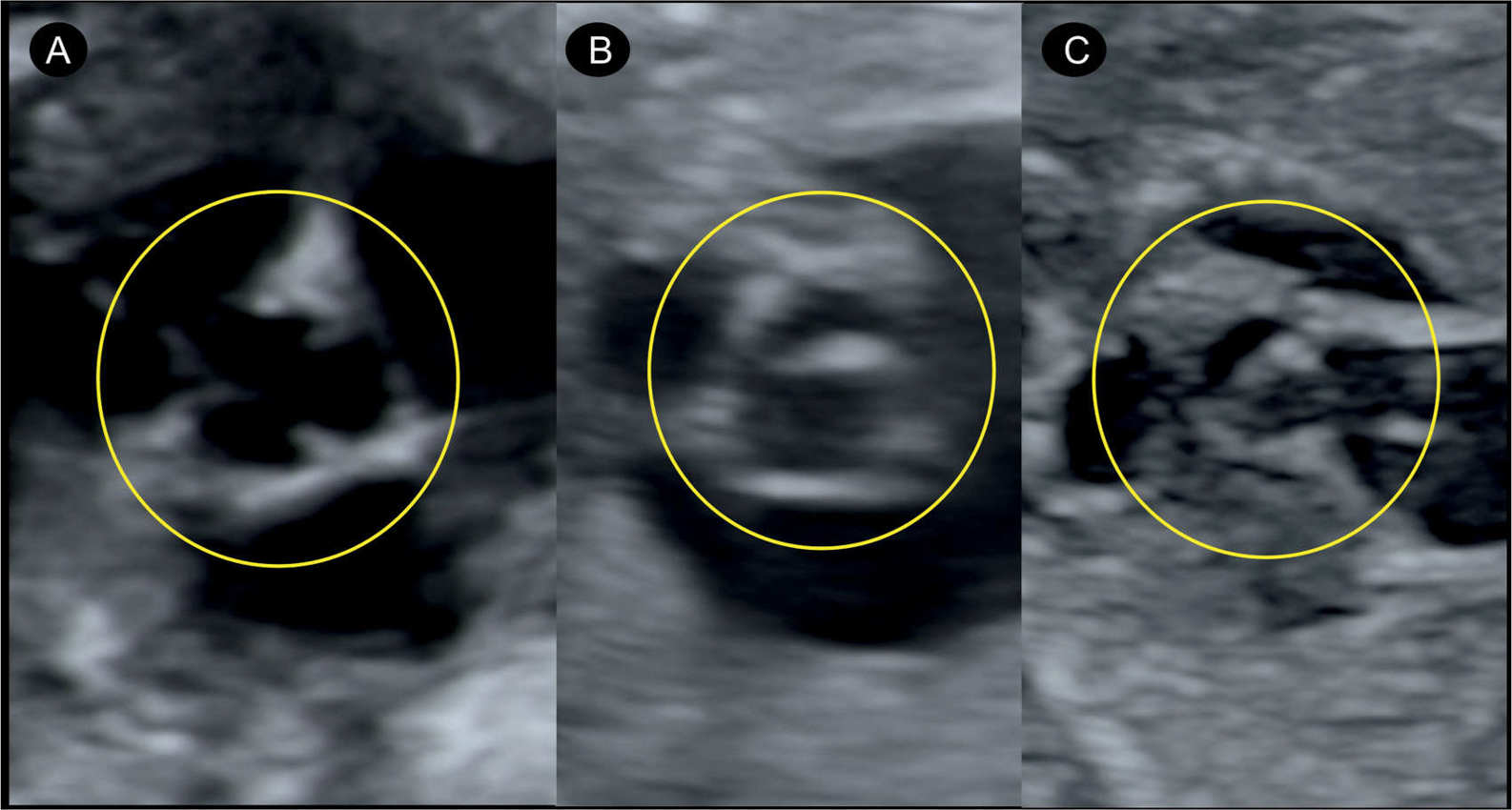

Mild aortic stenosis is difficult to detect prenatally due to a normal four-chamber anatomy in the majority of cases (Fig. 21.2A). The typical left ventricular myocardial hypertrophy found postnatally is absent or occasionally noted in late gestation. The five-chamber view may, however, show a poststenotic dilation of the ascending aorta (Figs. 21.2B and 21.3). This dilation can also be prominent and reach the transverse aortic arch and thus be seen in the three-vessel-trachea view. At the level of the aortic valve, thickened valve leaflets, doming of the cusps, and lack of complete valve opening during systole may be observed (Figs. 21.2B and 21.3). A cross section at the level of the aortic valve (short axis of right ventricle) may show the number of cusps and the presence of any thickening of the commissures (5) (Fig. 21.4).

Color Doppler

The detection of mild aortic stenosis is mainly achieved by the routine use of color Doppler with the detection of turbulent flow across the aortic valve (Figs. 21.5 to 21.7). The three-vessel-trachea view on color Doppler shows often a turbulent antegrade flow through a normal-size or slightly dilated transverse aortic arch (Fig. 21.7). Spectral Doppler reveals high peak systolic velocities of greater than 150 cm/s (Figs. 21.8 and 21.9). In a fetus with a normal left ventricular contractility, the higher the peak velocity the more severe is the stenosis. The shape of the Doppler envelope may show in these cases a slow acceleration to the peak velocity (Figs. 21.8 and 21.9).

Early Gestation

The diagnosis of mild aortic stenosis has been reported in early gestation (6). The authors have also diagnosed in few fetuses mild aortic stenosis by demonstrating elevated peak systolic velocities across the aortic valves (>100 cm/s) as compared to normal velocities across the pulmonary valves (30 cm/s) (Fig. 21.10). Poststenotic dilation of the aortic root was already noted in one of the cases (Fig. 21.10). In general, suspicion of aortic stenosis in early gestation is achieved either due to high velocities on the routine use of color Doppler or in the visualization of a dilated ascending aorta.

Figure 21.2: Fetus at 25 weeks with mild aortic stenosis showing a normal four-chamber view with normal left (LV) and right (RV) ventricles (A). In the five-chamber view (B) in systole, an incomplete valve opening is recognized (arrows) with a dilated aortic root (Ao) (double arrowhead). LA, left atrium.

Figure 21.3: Apical five-chamber view of the ascending aorta in two fetuses with valvular aortic stenosis. The incomplete opening of the aortic valve in systole with doming is recognized (yellow arrows). Poststenotic dilation of the ascending aorta (Ao) is noted, especially when compared with the diameter of the aortic root (double arrowheads) (see corresponding color Doppler images in Fig. 21.6). LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle.

Figure 21.4: Short-axis view at the level of the aortic root. In A, the three leaflets in a normal aortic valve are seen. Note in B and C thickened and fused valve leaflets in two fetuses with aortic stenosis.

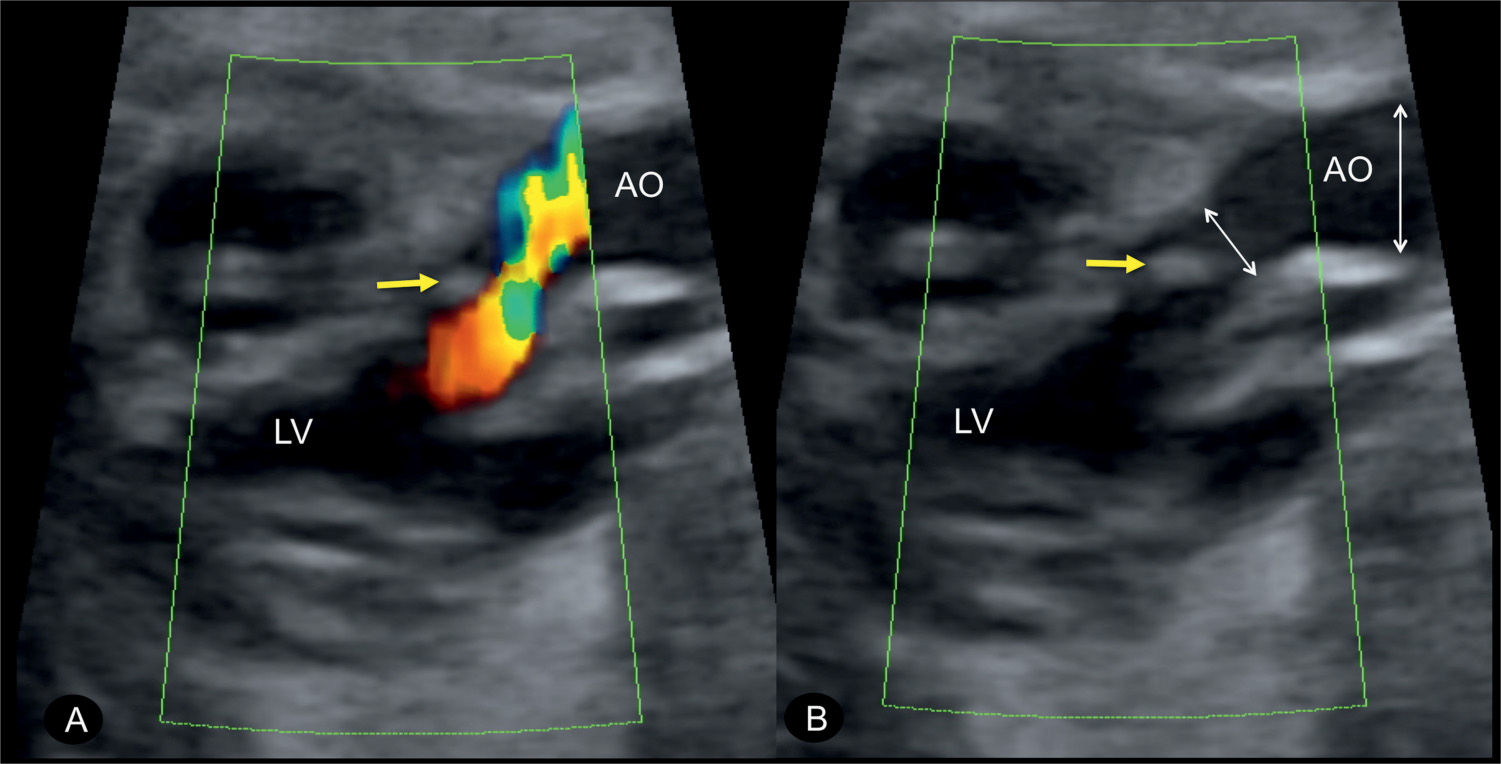

Figure 21.5: Parasagittal long-axis view of the left ventricular outflow tract in color Doppler in a fetus with simple aortic stenosis. A: In systole, blood flow from the left ventricle (LV) into the ascending aorta (AO) is turbulent, which enabled the diagnosis of aortic stenosis. B: Color Doppler information was switched off to better demonstrate the limited opening of the thickened aortic valve (small arrow). The typical poststenotic dilation is recognized in this case as well by comparing the caliber of the aortic root with the ascending aorta (two double arrowheads).

Three-Dimensional Ultrasound

Tomographic ultrasound imaging of a three-dimensional (3D) volume can demonstrate various features of aortic stenosis by displaying multiple planes at different anatomic levels. Application of spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) allows for evaluation of ventricular anatomy and contractility and can be used to monitor progress of disease. Surface-rendering mode combined with STIC can be used to obtain an en face plane of the stenotic aortic valve (Fig. 21.11). This is better achieved in the third trimester, but shadowing from the ribs can be a limiting factor. A similar view can be provided by using the biplane approach (see Chapter 15), visualizing the dysplastic valve in the left ventricular long-axis view and getting the corresponding 90 degrees orthogonal plane with an en face view of the valve (Fig. 21.12). Rendering of the ventricular volume using inversion mode can also be of help in differentiating ventricular contractility between the right and left ventricles. Turbulent color Doppler flow is best demonstrated with tomographic imaging and also in glass-body mode (Fig. 21.13).

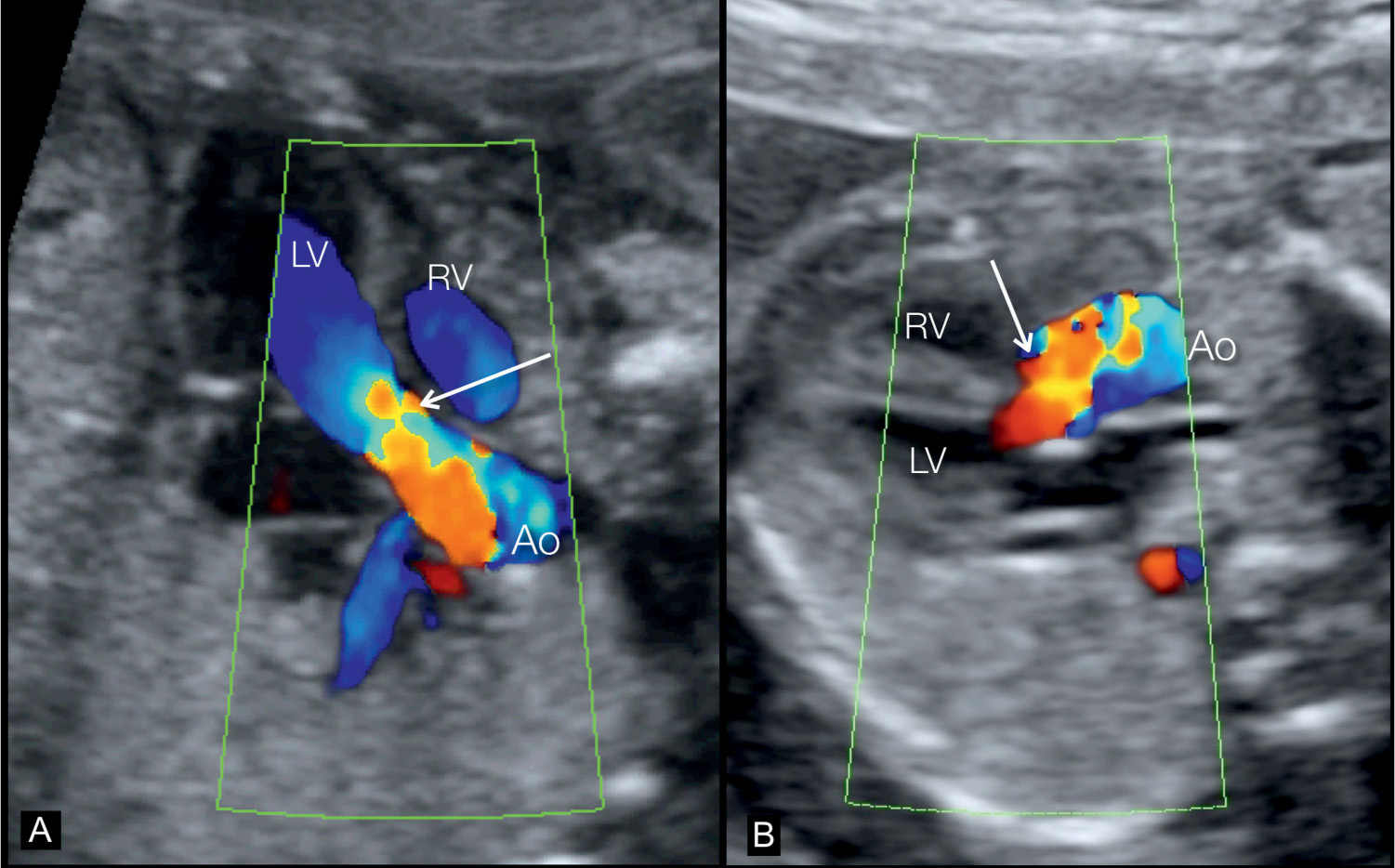

Figure 21.6: Apical (A) and transverse (B) five-chamber views during systole in two fetuses with aortic stenosis, showing the left ventricular outflow tract in color Doppler. The corresponding grayscale images are shown in Figure 21.3. Color Doppler clearly demonstrates turbulence in the ascending aorta (Ao) during systole (white arrows) recognized by the aliased color display. LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree