Background

Although alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking are common behaviors in reproductive-age women, little is known about the impact of consumption patterns on ovarian reserve. Even less is known about the effects of smoking and alcohol use in reproductive-age African-American women.

Objective

The objective of the study was to examine the impact of the patterns of alcohol intake and cigarette smoking on anti-Müllerian hormone levels as a marker of ovarian reserve in African-American women.

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional analysis from the baseline clinical visit and data collection of the Study of Environment, Lifestyle, and Fibroids performed by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. A total of 1654 volunteers, aged 23–34 years, recruited from the Detroit, Michigan community completed questionnaires on alcohol intake and cigarette smoking and provided serum for anti-Müllerian hormone measurement. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions were used as appropriate to estimate the effect of a range of exposure patterns on anti-Müllerian hormone levels while adjusting for potential confounders including age, body mass index, and hormonal contraception.

Results

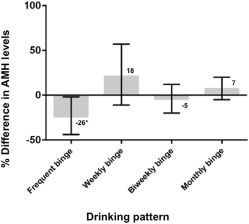

Most participants were alcohol drinkers (74%). Of those, the majority (74%) engaged in binge drinking at least once in the last year. Women who reported binge drinking twice weekly or more had 26% lower anti-Müllerian hormone levels compared with current drinkers who never binged (95% confidence interval, –44, –2, P < .04). Other alcohol consumption patterns (both past and current) were unrelated to anti-Müllerian hormone. The minority of participants currently (19%) or formerly (7%) smoked, and only 4% of current smokers used a pack a day or more. Neither smoking status nor second-hand smoke exposure in utero, childhood, or adulthood was associated with anti-Müllerian hormone levels.

Conclusion

Results suggest that current, frequent binge drinking may have an adverse impact on ovarian reserve. Other drinking and smoking exposures were not associated with anti-Müllerian hormone in this cohort of healthy, young, African-American women. A longitudinal study of how these common lifestyle behaviors have an impact on the variability in age-adjusted anti-Müllerian hormone levels is merited.

Anti-Müllerian hormone is a marker of ovarian reserve widely used in clinical practice and is increasingly used as a tool in epidemiological studies of potential ovarian toxicants. Despite educational campaigns on associated health risks, excessive alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking remain frequent behaviors in the United States.

Heavy alcohol consumption is increasingly common in reproductive-age women, even those seeking conception, and has been associated with decreased in vitro fertilization cycle success. Cigarette smoking has established adverse effects on short- and long-term fertility yet remains a common practice in the United States, where 1 in 5 women smoke. Accordingly, whether alcohol intake and smoking behaviors influence fertility is a question of significant public health concern.

Existing literature on alcohol intake and anti-Müllerian hormone levels is limited and suggests a possible differential impact of alcohol on anti-Müllerian hormone levels by ethnicity. Studies failed to identify a relationship with drinking and anti-Müllerian hormone levels or antral follicle count in predominantly white cohorts but suggest worse ovarian reserve testing among black South African women and Japanese women who drink. Disparate results may be attributable to racial differences in anti-Müllerian hormone, cultural differences in alcohol consumption not reflected by the exposure variables ascertained or methodological differences in characterizing the exposure.

Evaluation of the impact of cigarette smoking on anti-Müllerian hormone levels has also produced discordant findings, suggesting a differential impact by age. Among perimenopausal women, current smoking was associated with lower anti-Müllerian hormone levels. Whereas one large study identified an inverse, dose-dependent association of smoking with anti-Müllerian hormone levels, other investigations failed to reproduce an association between current smoking and anti-Müllerian hormone levels. The influence of passive smoke exposure on anti-Müllerian hormone has been sparsely studied, but one investigation demonstrated lower anti-Müllerian hormone levels among healthy black South African women who reported passive smoke exposure.

To characterize the influence of these common lifestyle exposures on ovarian reserve in the understudied African-American population, we assessed the duration, frequency, amount, and pattern of use (eg, binge drinking, cumulative alcohol exposure, cigarettes per day, and passive smoke exposure in utero, childhood, and adulthood). We hypothesized that increased frequency and duration of alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and second-hand smoke exposure would be associated with lower anti-Müllerian hormone levels.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

A volunteer community sample of 1696 African-American women in the Detroit, MI area were enrolled in an ongoing prospective cohort study, the Study of Environment, Lifestyle, and Fibroids, whose primary objective is to study the incidence of fibroids in African-American women. Participants were 23–34 years of age at the time of recruitment and without a known history of uterine leiomyomata at the time of examination from November 2010 through December 2012. Recruitment and data collection procedures have been previously described. Women with a history of hysterectomy, autoimmune disease, or any cancer treated with radiation or chemotherapy were excluded.

Eligible participants who completed telephone interviews, all enrollment questionnaires, and a clinic visit were enrolled. Participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National Institute of Environmental Health Services and the Henry Ford Health System.

Exposure ascertainment

Data on patient demographics and reproductive and medical histories were self-reported. Participants provided information on drinking, smoking, and passive smoke exposure via self-administered computer-assisted web interviewing questionnaires created specifically for use in the Study of Environment, Lifestyle, and Fibroids study. Comprehensive questionnaires assessed the duration, frequency, and amount of alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and second-hand smoke exposure both currently, defined as within the last year, and at the time of maximum consumption.

Women answered questionnaires regarding alcohol intake, including a history of regular drinking, age of initiation, number of drinks consumed in the last year and when drinking the most based on frequency of drinking and number of drinks consumed on days of consumption, frequency of binge drinking (4 or more drinks at a single occasion) in the last year and when drinking the most.

Women were categorized as ever drinkers if they reported a history of drinking at least 10 drinks in any 1 year and current drinkers if they reported drinking at least 10 drinks in the last year. Binge drinking was defined as consumption of 4 or more drinks on one occasion. Consumption level was categorized as low (drinking less than once a week and never binging), moderate (drinking up to 2 days per week or binge drinking no more than monthly), and heavy (drinking more than 2 days per week or binging twice monthly or more). Cumulative alcohol exposure was denoted by level of consumption (low, moderate, high) and duration of drinking (years). In women with a history of heavy alcohol consumption, the impact of current drinking was assessed to evaluate the permanence of any association with heavy drinking and anti-Müllerian hormone levels.

Smoking questionnaires assessed a history of ever smoking, age of initiation, age of cessation for past smokers, and current number of cigarettes smoked per day as well as the number of cigarettes smoked per day at the time of heaviest consumption. Regular smoking was defined as smoking at least 1 cigarette per day for more than 6 months.

Participants answered questions regarding second-hand, or passive, smoke exposure, including caregiver smoked in the home in childhood, the number of years living with smoker in childhood, in utero smoke exposure, current passive smoke exposure in the home, proportion of time in adulthood living with smoker in home, and the total number of hours per week when the participant can smell tobacco smoke.

Passive exposure to smoke in utero, childhood, and adulthood were also assessed. To capture the impact of second-hand smoke as both an isolated and cumulative smoke exposure, passive exposure was separately assessed in nonsmokers and again in all women.

Participants provided serum for anti-Müllerian hormone measurement during their clinic visit. Cycle day was not included in our analysis because of the low inter- and intracycle variability with anti-Müllerian hormone. Stored serum aliquots were assayed at the Clinical Laboratory Research Core within the Pathology Department at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA).

Serum anti-Müllerian hormone was measured using the pico-anti-Müllerian hormone enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (lower limit of detection 0.0016 ng/mL, 1 ng/mL = 7.14 pmol/L) (Ansh Labs, Webster, TX). Samples were run at a 1:10 dilution, and then neat for the samples that were low. Anti-Müllerian hormone values that remained below the lower limit of detection (n = 3) were assigned a value of 0.0011 ng/mL using an established formula. The anti-Müllerian hormone enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay has intra- and interassay coefficients of variation 6.9% and 6.5%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The relationship among alcohol consumption variables and anti-Müllerian hormone levels in the cohort were assessed using multivariable-adjusted linear and logistic regression models. Anti-Müllerian hormone levels were log transformed to account for nonnormal distribution, and all models were adjusted for age, body mass index, and current hormonal contraception, variables that were previously shown to be significantly associated with anti-Müllerian hormone levels in this cohort.

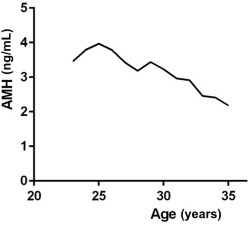

Recognizing the nonlinear association between age and ovarian reserve, main effects models included both an age and an age quadratic term. Considering the natural, age-related decline in anti-Müllerian hormone levels occurring at 25 years, sensitivity analyses were performed to examine interactions between age and exposure variables. This allowed for an age-related decline in anti-Müllerian hormone to differ between exposed compared with unexposed participants.

Because nondrinkers may represent a highly selected group in the United States, as suggested by a J-shaped distribution for the effects of alcohol on adverse health outcomes, a separate analysis was restricted to current drinkers, as has been done in previous investigations.

Linear regression models with log anti-Müllerian hormone as the dependent variable generated adjusted estimates of β associated with each exposure of interest. Percentage differences and 95% confidence intervals in serum anti-Müllerian hormone between exposure groups were calculated from the βs as follows ([exp(β) – 1] * 100) and presented with corresponding 95% confidence intervals or P values. Significant associations in linear regression models were further explored in multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models to assess the odds of diminished ovarian reserve (DOR), defined as anti-Müllerian hormone <1, and confidence intervals.

All analyses were carried out using Statistical Analysis Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables are presented as means or medians with (SD or interquartile ranges). Potential confounders were assessed using simple linear regression and were considered for addition to the final model if they changed the risk ratio by more than 10%. Statistical significance was assumed for P < .05.

Results

A total of 1654 reproductive-aged African-American women submitted comprehensive questionnaires on alcohol consumption and provided serum for anti-Müllerian hormone measurement. The mean age of participants was 29 years, median serum anti-Müllerian hormone concentration was 3.2 ng/mL, and most women were obese with a median body mass index of 32 kg/m 2 . Additional demographic details are presented in Table 1 and median anti-Müllerian hormone levels by age are presented in Figure 1 .

| Demographic characteristic | n = 1654 (100) a |

|---|---|

| AMH, ng/mL (median, IQR; range) | 3.2, 1.7–5.3; <0.002–39 |

| Age, y (mean ± SD; range) b | 29 ± 4; 23–35 |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 (median, IQR; range) c | 32, 26–40; 16–79 |

| Education, % | |

| High school or less | 367 (22) |

| Some college but no degree | 623 (38) |

| Bachelor’s, associate, or graduate degree | 663 (40) |

| Mean number of pregnancies (mean ± SD range) d | 3 ± 2; 1–15 |

| Current contraception use, % | 454 (27) |

| History of polycystic ovarian syndrome, % | 52 (3) |

| Drinking | |

| Never | 438 (26) |

| Ever | 1216 (74) |

| Former | 48 (3) |

| Current | 1168 (71) |

| Smoking | |

| Never | 1213 (73) |

| Former | 123 (7) |

| Current | 318 (19) |

| <10 cigarettes/day | 233 (14) |

| 10–14 cigarettes/day | 57 (3) |

| 15+ cigarettes/day | 28 (2) |

| In utero smoke exposure e | |

| Yes | 160 (13) |

| No | 1053 (87) |

| Childhood smoke exposure f | |

| Yes | 633 (55) |

| No | 513 (45) |

| Current second-hand smoke exposure g | |

| Yes | 204 (17) |

| No | 1008 (83) |

a n (%) = 1654 (100), unless otherwise indicated. Column totals may not sum to 100% because of rounding

b Women aged 23–34 years were recruited; some were 35 years old by the time all baseline activities and enrollment were completed

f Among 1146 never-smokers; 67 missing

Alcohol consumption

The majority (74%) of participants reported current (71%) or former (3%) drinking. The average age of drinking initiation was 20 (±3.3) years and most drinkers (84%) reported their heaviest consumption occurred after their teen years. Of all participants, 25% reported weekly or more frequent drinking and 54% reported binge drinking in the last year. When the analysis was restricted to women who currently drink (n = 1168), most (74%) reported binge drinking in the last year, and of these, 26% reported binging multiple times per month.

When drinkers and nondrinkers (reference category) were compared, there were no significant associations between anti-Müllerian hormone levels and any of the numerous drinking behaviors assessed, including past and current behaviors ( Table 2 ). This included no association of current alcohol intake with anti-Müllerian hormone levels among women with a history of prior heavy alcohol intake. However, those who binge drank twice a week or more had a 21% lower anti-Müllerian hormone level compared with those who never drink (95% confidence interval, –41 to 7) ( Table 2 ).

| Alcohol variables | Descriptive statistics | % Δ in AMH b (95% CI) c |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample | n =1654 (100) | |

| Drinking status | ||

| Ever-drinkers | 1216 (74) | 3 (–8, 16) |

| Current drinkers | 1168 (71) | 3 (–9, 16) |

| Former drinkers | 48 (3) | 8 (–22, 49) |

| Never-drinkers | 438 (26) | Referent |

| Alcohol intake during years drank | ||

| Heavy | 330 (20) | 0 (–14, 17) |

| Medium | 755 (46) | 4 (–9, 18) |

| Low | 131 (8) | 8 (–13, 33) |

| Never-drinkers | 438 (27) | Referent |

| Cumulative alcohol exposure a | ||

| Heavy intake, ≥10 y | 118 (7) | 3 (–18, 28) |

| Heavy intake, 5–9 y | 104 (6.5) | –7 (–26, 18) |

| Heavy intake, 1–4 y | 108 (7) | 4 (–17, 32) |

| Medium intake, ≥10 y | 143 (9) | 7 (–14, 31) |

| Medium intake, 5–9 y | 247 (15) | –4 (–19, 14) |

| Medium intake, 1–4 y | 365 (22) | 8 (–7, 25) |

| Low intake, ≥10 y | 8 (0.5) | –6 (–56, 101) |

| Low intake, 5–9 y | 22 (1) | 6 (–34, 69) |

| Low intake, 1–4 y | 101 (6) | 9 (–14, 38) |

| Never-drinkers | 438 (26) | Referent |

| Current vs never-drinkers | n =1606 (97) | |

| Current intake | ||

| Heavy | 347 (22) | –1 (–15, 16) |

| Medium | 562 (35) | 6 (–8, 21) |

| Low | 259 (16) | 3 (–13, 22) |

| Never-drinkers | 438 (27) | Referent |

| Binging in last year | ||

| ≥2 times per week | 58 (4) | –21 (–41, 7) |

| Once a week | 63 (4) | 20 (–10, 61) |

| 2–3 times per month | 189 (12) | –1 (–18, 20) |

| Once a month or less | 556 (35) | 7 (–6, 23) |

| None | 302 (19) | 0 (–15, 17) |

| Never-drinkers | 438 (27) | Referent |

| Current intake in past heavy drinkers a | n = 1108 | |

| Heavy past, heavy current | 330 (30) | 0 (–15, 18) |

| Heavy past, medium current | 242 (22) | 1 (–16, 21) |

| Heavy past, low current | 98 (9) | 8 (–17, 39) |

| Never-drinkers | 438 (40) | Referent |

a Among 670 women with a history of heavy past drinking and 438 never-drinkers

b Calculated using the following formula: (exp[β] – 1) * 100

c Multivariable-adjusted model adjusted for age, quadratic age 2 , BMI, and hormonal contraception use.

When analyses were limited to current drinkers, the influence of high frequency binging on anti-Müllerian hormone levels was stronger. Women who reported binge drinking twice weekly or more frequently had 26% lower anti-Müllerian hormone levels compared with current drinkers who never binged (95% confidence interval, –44, to –2; P = .036, Figure 2 ). This did not translate to increased odds of diminished ovarian reserve (odds ratio, 0.85, 95% confidence interval, 0.5–2.7, P = .39). Figure 1 demonstrates associations between binge drinking patterns and anti-Müllerian hormone levels among current drinkers. There was no association with teenage drinking, frequency or duration of drinking, current heavy drinking, or ever binging (results not presented).

Cigarette smoking

Most women (73%) never smoked regularly, 7% formerly smoked, and 19% were current smokers. Among current smokers, only 4% smoked a pack or more a day. The average age of smoking initiation was 18 (±4) years, cessation was 25 (±4) years, and the average duration of smoking was 6 (±5) years, none of which were associated with anti-Müllerian hormone levels (all P > .05, Table 3 ).

| Cigarette smoking variables | Descriptive statistics | % Δ in AMH (95% CI) a |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | n = 1654 (100) | |

| Smoking status, % | ||

| Current | 318 (19) | 1.9 (–11, 17) |

| Former | 123 (7) | 7.5 (–12, 32) |

| Never | 1213 (73) | Referent |

| Age at initiation of smoking, y, % | ||

| 15 or younger | 82 (5) | 9.2 (–14, 39) |

| 15–18 | 175 (11) | 9.7 (–8, 30) |

| 19–20 | 71 (4) | –3.2 (–25, 26) |

| 21–23 | 74 (5) | 3.0 (–20, 33) |

| ≥24 | 39 (2) | –20.0 (–44, 14) |

| Never-smokers | 1213 (73) | Referent |

| Current smokers | n = 1531 (93) | |

| Current consumption | ||

| <10 | 233 (15) | –1 (–16, 15) |

| 10–14 | 57 (4) | 10 (–18, 48) |

| 15–19 | 16 (1) | 32 (–24, 126) |

| ≥20 | 12 (1) | –7 (–50, 74) |

| Never-smokers | 1213 (79) | Referent |

| Maximum consumption, cigarettes/d | ||

| <10 | 179 (12) | –2 (–17, 17) |

| 10–14 | 58 (4) | 5 (–22, 40) |

| 15–19 | 44 (3) | 18 (–16, 64) |

| ≥20 | 37 (2) | –3 (–33, 39) |

| Never-smokers | 1213 (79) | Referent |

| Years of smoking, y | ||

| <1 | 6 (0.4) | 46 (–44, 283) |

| 1–2 | 14 (1) | –40 (–66, 8) |

| 3 or more | 298 (19) | 4 (–10, 19) |

| Never-smokers | 1213 (79) | Referent |

| Former smokers | n = 1336 (81) | |

| Max consumption, cigarettes/d | ||

| <10 | 96 (7) | 8 (–15, 37) |

| ≥10 | 27 (2) | 7 (–30, 64) |

| Never-smokers | 1213 (91) | Referent |

| Years of smoking, y | ||

| <1 | 7 (1) | –13 (–62, 99) |

| 1–2 | 31 (2) | –1 (–33, 48) |

| 3 or more | 84 (6) | 14 (–11, 46) |

| Never-smokers | 1213 (91) | Referent |

| Never-smokers | n = 1213 (73) | |

| In utero exposure | ||

| Yes or probably yes | 160 (13) | 5 (–13, 28) |

| No or probably no | 1053 (87) | Referent |

| Childhood second-hand smoke exposure b | ||

| Yes | 633 (55) | 9 (–5, 25) |

| No | 513 (45) | Referent |

| Childhood years living with smoker(s), y | ||

| 1 | 91 (8) | 12 (–13, 44) |

| 2 | 65 (5) | –12 (–34, 19) |

| 3 | 42 (4) | 29 (–10, 86) |

| 4–6 | 67 (6) | –2 (–26, 31) |

| 7–9 | 54 (4) | –11 (–34, 25) |

| 10 or more | 373 (31) | 11 (–5, 29) |

| None | 521 (43) | Referent |

| Time as adult living with smoker in home | ||

| Very little of the time | 241 (20) | 11 (–6, 32) |

| Less than half the time | 123 (10) | 10 (–12, 37) |

| More than half the time | 190 (16) | 7 (–12, 28) |

| None of the time | 659 (54) | Referent |

| Currently lives with smoker in home c | ||

| Yes | 204 (17) | –1 (–17, 18) |

| No | 1008 (83) | Referent |

| Time able to currently smell smoke, h/d | ||

| <1 | 533 (44) | 4 (–10, 21) |

| 1 | 154 (13) | 1 (–19, 25) |

| 2 | 23 (2) | –1 (–39, 59) |

| 3–4 | 54 (4) | 1 (–27, 40) |

| 5–9 | 40 (3) | –5 (–34, 38) |

| 10+ | 18 (1) | –31 (–60, 20) |

| Unexposed | 391 (32) | Referent |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree