Perinatal depression is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality and may have long-term consequences on child development. The US Preventive Services Task Force has recently recognized the importance of identifying and treating women with depression in the perinatal period. However, screening and accessing appropriate treatment come with logistical challenges. In many areas, there may not be sufficient access to psychiatric care, and, until these resources develop, the burden may inadvertently fall on obstetricians. As a result, understanding the risks of perinatal depression in comparison with the risks of treatment is important. Many studies of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy fail to control for underlying depressive illness, which can lead to misinterpretation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor risk by clinicians. This review discusses the risks and benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment in pregnancy within the context of perinatal depression. Whereas selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be associated with certain risks, the absolute risks are low and may be outweighed by the risks of untreated depression for many women and their offspring.

Recently the US Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening perinatal women for depression. This has followed similar corresponding recommendations from professional associations, including the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Perinatal depression affects nearly 20% of women in pregnancy and in the postpartum. Screening helps identify women who would benefit from psychiatric treatment and reduce depressive symptoms at this vulnerable time.

Nevertheless, screening comes with challenges. Deciding which type of practitioner should conduct depression screening is not straightforward. Obstetrician-gynecologists are often the primary medical providers for women and may be in a unique position to identify women in need of psychiatric treatment during the perinatal period in particular. However, having a system in place for diagnosis and treatment after at-risk women are identified is crucial. Recent studies have shown that depression screening accompanied by provider support improves maternal outcomes.

Access to general psychiatrists can be difficult, and access to psychiatrists with expertise in the perinatal period may be even more difficult. The burden may inadvertently fall on obstetrician-gynecologists. There are inherent risks to taking on this role, including the risk of misdiagnosis, problematic decisions such as prescribing an antidepressant to a patient with bipolar depression, and the risks of withholding treatment from women who have depression with significant associated morbidity. Consequently, being knowledgeable gatekeepers to psychiatric care, especially in regard to depression management in pregnancy, is essential for obstetrician-gynecologists. This article will discuss the role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of antenatal depression.

The risk-risk analysis

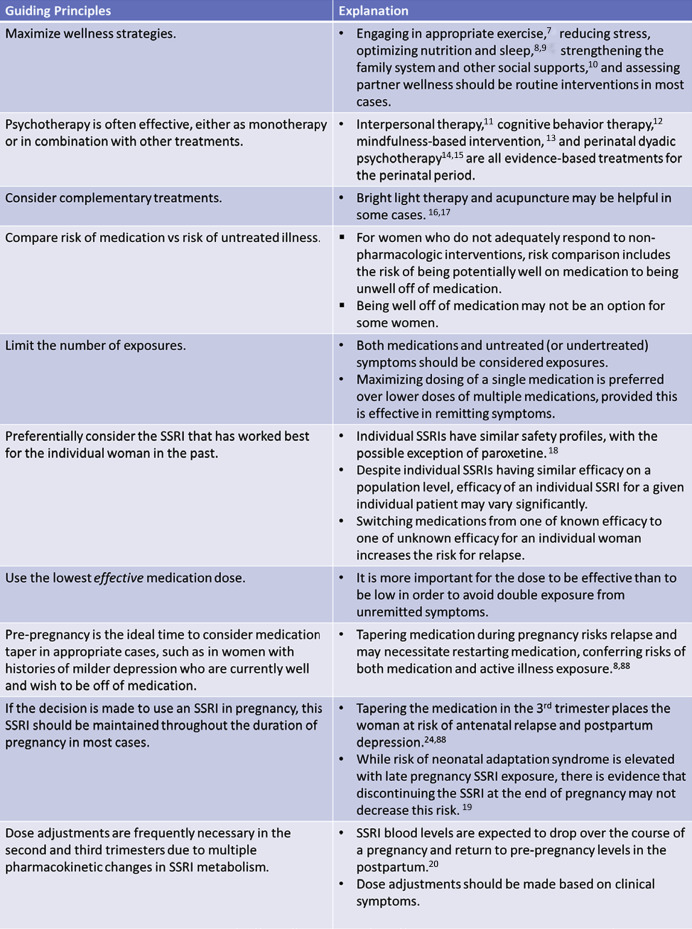

When appropriate, it is important to maximize nonpharmacological interventions, including psychotherapy, for the treatment of perinatal depression ( Figure 1 ). For women with milder depression, a trial off of antidepressant treatment prior to conception may be appropriate. However, women with major depressive disorder are at high risk of relapse in pregnancy with discontinuation of antidepressant treatment.

Depending on severity, some women may require pharmacotherapy for the treatment of their depression during pregnancy. Antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, are considered first line. Treatment decisions in regard to pharmacotherapy must weigh the relative risks of medication exposure against the risks of untreated maternal depression.

Risk of antenatal and postpartum depression

Perinatal depression can have detrimental effects on the fetus and developing child. Antenatal depression has been associated with unhealthy lifestyle choices, including smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, and using illicit drugs, variables that have been associated with adverse outcomes, including congenital malformations. In addition, perinatal psychiatric illness and, specifically, perinatal depression are associated with a high risk of suicide.

Fetal exposure to maternal psychiatric illness may increase the risk of poor obstetric outcomes, including preterm birth <32 weeks’ gestation, admission to a neonatal intensive care unit, a prolonged hospital stay, and cesarean delivery. Prenatal depression is associated with physiological changes in the offspring and changes in the markers of fetal neurodevelopment.

Maternal psychological distress has been associated with epigenetic changes in the placenta, which may have life-long consequences for exposed offspring. Antenatal maternal depression may adversely affect neurodevelopment and has been associated with behavioral problems and psychiatric illness in the offspring.

Prenatal depression is a major risk factor for postpartum depression, and postpartum depression can have long-term detrimental effects on a child’s neurodevelopment and mental health. Postpartum depression may interfere with bonding and attachment with long-lasting physiological effects on offspring. The duration of a mother’s depression has been associated with lower global cognitive index, and the number of maternal depressive episodes after delivery has been negatively associated with language in the child.

Children with a depressed parent are 3 times more likely to develop depression and anxiety and are 4 times as likely to have had poor functioning, risks that extend into adulthood. Importantly, there is evidence that treating a mother’s depression can lead to improvement in the child’s depressive symptoms.

Risk of antenatal and postpartum depression

Perinatal depression can have detrimental effects on the fetus and developing child. Antenatal depression has been associated with unhealthy lifestyle choices, including smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, and using illicit drugs, variables that have been associated with adverse outcomes, including congenital malformations. In addition, perinatal psychiatric illness and, specifically, perinatal depression are associated with a high risk of suicide.

Fetal exposure to maternal psychiatric illness may increase the risk of poor obstetric outcomes, including preterm birth <32 weeks’ gestation, admission to a neonatal intensive care unit, a prolonged hospital stay, and cesarean delivery. Prenatal depression is associated with physiological changes in the offspring and changes in the markers of fetal neurodevelopment.

Maternal psychological distress has been associated with epigenetic changes in the placenta, which may have life-long consequences for exposed offspring. Antenatal maternal depression may adversely affect neurodevelopment and has been associated with behavioral problems and psychiatric illness in the offspring.

Prenatal depression is a major risk factor for postpartum depression, and postpartum depression can have long-term detrimental effects on a child’s neurodevelopment and mental health. Postpartum depression may interfere with bonding and attachment with long-lasting physiological effects on offspring. The duration of a mother’s depression has been associated with lower global cognitive index, and the number of maternal depressive episodes after delivery has been negatively associated with language in the child.

Children with a depressed parent are 3 times more likely to develop depression and anxiety and are 4 times as likely to have had poor functioning, risks that extend into adulthood. Importantly, there is evidence that treating a mother’s depression can lead to improvement in the child’s depressive symptoms.

Risk of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors specific to pregnancy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors cross the placenta, with cord/maternal concentration ratios ranging from 0.15 (paroxetine) to 0.86 (N-desmethylcitalopram, active metabolite of citalopram). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants in pregnancy, with up to 10.2% of pregnant women filling a prescription. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors include sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, and escitalopram. The term serotonin reuptake inhibitor is a broader category including antidepressants with a high affinity for the serotonin transporter and often includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Although there are large population-based studies of antenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure, for ethical reasons, there are no randomized controlled trials, and therefore, correlations are vulnerable to confounders. Confounding by indication has been a particular problem for this body of literature because the effects of perinatal depression on fetal and infant well-being are so profound. Studies that have failed to adequately control for perinatal depression have led to much misinterpretation with regard to risk of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure among clinicians.

Conception

The study by Nillni et al , which controlled for important confounding factors, including confounding by indication, did not find an association between current selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and fecundability. However, current severe depression was associated with decreased fecundability. There does not appear to be a difference in the rate of pregnancy via in vitro fertilization with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure.

Miscarriage

Literature on the risk of miscarriage with antenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure is conflicting. Ban et al , in a study of 512,574 pregnancies, found an increased risk of miscarriage with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure compared with exposure to unmedicated depression or anxiety in the first trimester (relative risk ratio, 1.4, 99% confidence interval, 1.2–1.7). In addition, women on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in the first trimester had a marginally statistically significant increased risk of miscarriage compared with women who stopped the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (relative risk ratio, 1.2, 99% confidence interval, 1.0–1.3). However, the study did not control for severity of mental illness, and severity of illness in women who decide to not take or to discontinue a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor may differ from the severity of illness in women who decide to continue selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment in pregnancy.

Other studies have not supported an association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and miscarriage. Andersen et al , in a study of 1,279,840 pregnancies, found no difference in the hazard ratio of miscarriage with exposure to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in early pregnancy compared with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure prior to pregnancy.

Johansen et al , in a study of 1,191,164 pregnancies, found that the hazard ratio for first-trimester miscarriage was higher for women who stopped selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors prior to pregnancy than for women on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy. In addition, women on an selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in pregnancy but without recent maternal diagnosis of depression or anxiety had a lower hazard ratio for miscarriage in the first trimester than women with a diagnosis of depression or anxiety but not on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. These results highlight the importance of controlling for confounding by indication.

First trimester exposure

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors do not appear to be teratogens. Whereas findings in the literature have been conflicting, multiple large studies that attempted to control for confounding by indication did not find an association between major congenital malformations and in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a class. Huybrechts et al found that, after restricting to women with depression and adjusting, there was no statistically significant association between first-trimester exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cardiac malformations. Sibling-controlled analyses by Furu et al did not find a statistically significant association between birth defect in general or cardiac malformation specifically and first-trimester exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Some studies found an association between first-trimester exposure to paroxetine and cardiac malformations; however, many of these studies did not control adequately for confounding by indication. Berard et al conducted a (nested) case-control study that adjusted for various potential confounders including maternal depression and found a marginally significant association between major cardiac malformations and exposure to >25 mg of paroxetine daily (odds ratio, 3.07, 95% confidence interval, 1.00–9.42). This study did not find an association between paroxetine in general, or paroxetine at lower doses, and major cardiac malformations.

Ban et al found that, compared with offspring of mothers with a recent diagnosis of depression, first-trimester exposure to paroxetine was associated with a marginally statistically significant increased risk of cardiac anomaly (odds ratio, 1.67, 95% confidence interval, 1.00–2.80). The majority of the cardiac anomalies of offspring exposed in utero to paroxetine were mild. Huybrechts et al did not find an association between first-trimester exposure to paroxetine and either cardiac malformations in general or specifically right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Taken together, those data do not support increased ultrasound monitoring in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-exposed fetuses for cardiac malformations such as fetal echocardiography with the possible exception of paroxetine.

Late pregnancy exposure

In some but not all studies, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn has been associated with late-pregnancy exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. In the general population, persistent pulmonary hypertension occurs in 1–2 per 1000 live births. The increased rate of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn with in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors has ranged from no increased risk to a 6-fold increased risk. Huybrechts et al found that the risk was attenuated and only marginally statistically significant after attempting to control for confounding factors, including confounding by indication (odds ratio, 1.28, 95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.64).

Delivery

Obstetric outcomes after in utero selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure have been studied. Low birthweight and earlier gestational age at delivery have been associated with in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in some but not all studies, and there is evidence that at least some of the association may be due to the underlying psychiatric illness.

Grzeskowiak et al found an increased risk of preterm delivery (<37 weeks’ gestation) and low birthweight (<2500 g) after in utero exposure to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor compared with the presence of maternal psychiatric illness in pregnancy; the authors were unable to adjust for the severity of psychiatric illness. Oberlander et al. 2006 found that, with propensity score matching to control for severity of maternal psychiatric illness, depressed mothers on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors had increased risk of having a child with birth weight <10% for gestational age, but did not find a statistically significant difference in risk of delivering prior to 37 weeks gestation. Yonkers et al. 2012 did not show a statistically significant association between antenatal serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure and preterm birth after controlling for severity of psychiatric illness. This study found an association between late but not early preterm birth and serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero; however, these results were not adjusted for psychiatric illness severity, an adjustment which had attenuated the association between any preterm birth and serotonin reuptake inhibitors. In addition, Nordeng et al. 2012 did not find an association between antenatal maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and preterm birth (<37 weeks gestation) or low birth weight (<2,500g) after adjusting for maternal depression and other important confounding variables, though there had been an association prior to adjusting. Depression itself has also been associated with these obstetric outcomes in some but not all studies. There is limited evidence that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may even mitigate some of this risk from psychiatric diagnosis as it pertains to preterm birth and cesarean section.

While inconsistent in the literature, multiple large studies that control for confounding by indication did not find an association between cesarean section and antenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. In a study by Oberlander et al , using a propensity score–matched analysis to control for severity of maternal mental illness, exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors plus maternal depression was not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of cesarean delivery compared with exposure to maternal depression alone, although it had been prior to propensity score matching.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may increase the risk of bleeding, particularly upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Studies examining whether in utero exposure to antidepressants increases the risk of postpartum hemorrhage have yielded inconsistent findings. When an association was found, the relative risk remained small. Palmsten et al found that women exposed to a serotonin reuptake inhibitor at delivery were at an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage (relative risk, 1.47, 95% confidence interval, 1.33–1.62) compared with the women unexposed after adjusting for confounding variables potentially associated with risk of bleeding.

In the study by Grzeskowiak et al , antidepressant exposure in late pregnancy increased a woman’s risk of primary postpartum hemorrhage (relative risk, 1.53, 95% confidence interval, 1.25–1.86) and severe primary postpartum hemorrhage (blood loss of at least 1000 mL) (relative risk, 1.84, 95% confidence interval, 1.39–2.44) compared with unexposed women. In contrast, Lupattelli et al did not find an association between late-pregnancy serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure and postpartum hemorrhage (>500 mL blood loss).

After delivery

A common adverse effect of antenatal exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors is neonatal adaptation syndrome, which is thought to be transient and not dangerous. Signs of neonatal adaptation syndrome include tremors, jitteriness, restlessness, irritability, changes in muscle tone, or respiratory distress and are often mild. These symptoms usually begin within the first 24–48 hours after delivery and often resolve within days, although they have been reported up to 1 month. Neonatal adaptation syndrome occurs in about one third of newborns after in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, compared with approximately one tenth of unexposed newborns.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in pregnancy has been associated with lower 5 minute Apgar score and with neonatal intensive care unit admission. Further studies are needed to clarify whether neonatal intensive care unit admission and lower 5 minute Apgar score are related to the transient symptoms of neonatal abstinence syndrome. In addition, the increased neonatal intensive care unit admission rate may be related to bias from increased monitoring of women on psychiatric medications.

Long-term neurodevelopment

Antenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors does not appear to have a major negative impact on neurodevelopment, although some risks have been identified.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been associated with changes in fetal neurodevelopment, including activity during non–rapid eye movement sleep and increased motor activity. Whereas offspring exposed in utero to a serotonin reuptake inhibitor have been found to have delayed psychomotor skill development, there is evidence that this difference may be transient and still within normal limits. Literature examining antenatal serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure and language or cognition is also reassuring.

Some but not all studies have found an association between internalizing behaviors, such as anxiety, in childhood and in utero exposure to antidepressants after adjusting for maternal psychiatric illness. Antenatal serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure does not appear to confer risk to externalizing problems in the offspring. There is also evidence for an association between maternal depression and behavioral problems in the offspring.

Multiple studies have examined whether antenatal antidepressant exposure is associated with autism spectrum disorders, and current literature is conflicting. El Marroun et al found an association between in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and autistic traits in offspring compared with exposure to depression. When other studies were restricted to only women with an affective disorder diagnosis or with a history of anxiety or mood disorder, there was no longer a statistically significant association. This suggests that the original associations prior to restriction may have been due to confounding factors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree