Neonatal Encephalopathy

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal encephalopathy is an important clinical condition with which all providers of newborn care should be familiar. It is a condition that is defined and characterized by the findings on physical examination and includes combinations of abnormalities in level of consciousness, muscle tone, activity, reflexes, brainstem function/breathing patterns, seizures, and ability to feed. In the past, these findings have been equated with hypoxia-ischemia or asphyxia as an etiology; however, more comprehensive assessments of neonatal encephalopathy indicated that a casual relationship between encephalopathy and hypoxia-ischemia is not as common as previously thought. What has emerged is the concept that neonatal encephalopathy is a phenotype for a broad array of potential diagnoses in the neonatal period and is without any preconceived implications regarding the timing of events that precipitate neonatal encephalopathy. The term neonatal rather than newborn encephalopathy is more appropriate because this is a condition that may be present at birth or develop at some time after birth. Thus, the objectives of this chapter are to provide an overview of

1. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy

2. Outcome of infants with neonatal encephalopathy

3. Spectrum of diagnoses that may be associated with neonatal encephalopathy

INCIDENCE OF NEONATAL ENCEPHALOPATHY

Meaningful information regarding the incidence of neonatal encephalopathy can only be derived from population-based studies. This type of study avoids referral bias because hospital-based (even tertiary hospitals) studies represent referral centers. Other methodological considerations include case ascertainment (retrospective reviews without clear definitions vs prospective data collection with a priori definitions) and use of the appropriate denominator of infants at risk for neonatal encephalopathy.1 Estimates of the incidence of neonatal encephalopathy prior to the mid-1990s have been limited to small studies that were not population based and focused on intrapartum events to determine the presence or absence of hypoxia-ischemia. Since that time, there have been 3 population-based studies to examine the epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy, but all represent work from more than 10 years ago.

A population-based, unmatched, case-control study was performed between 1993 and 1995 of infants with encephalopathy born in Western Australia around the metropolitan area of Perth.2 All cases of moderate or severe encephalopathy were referred to 1 of 2 tertiary neonatal intensive care units. This investigation focused on term infants in the first week of life using predetermined inclusion criteria of encephalopathy. Inclusion criteria were purposefully broad and included any 2 of specific variables, which needed to last more than 24 hours (abnormal consciousness, difficulty maintaining respirations of a presumed central origin, difficulty feeding, or abnormal tone and reflexes) or seizures alone. Deaths in the first week of life were reviewed to avoid exclusion of infants dying prior to transfer with evidence of encephalopathy. During the study interval, 164 cases of neonatal encephalopathy were identified. The incidence of neonatal encephalopathy was 3.8 per 1000 live term births (95% confidence interval, 3.2–4.4).

During the same years, 1993–1995, a population-based assessment of neonatal encephalopathy was conducted in the Thames region of the United Kingdom.3 Term infants were identified if they fulfilled deliberately overinclusive criteria similar to those of Badawi et al.2 Infants with trisomy 21 were excluded unless they fulfilled inclusion criteria that could not be attributable to trisomy 21; although this presumably represents a small number of infants, it is unclear how it was determined if infants with trisomy 21 were excluded. There were 150 cases of neonatal encephalopathy identified during a study period with 57,159 term births, including 97 term stillbirths. Based on these data, the incidence of neonatal encephalopathy was 2.62 per 1000 term births (95% confidence interval, 2.20–3.04). A subsequent observational population-based study was conducted in 2000 from the North Pas-de-Calais area of France.4 This region is well organized for perinatal services, and the study was planned with input from individuals from all level II and III centers. Cases were term infants in the first week of life who fulfilled inclusion criteria of Badawi et al.2 Infants with chromosomal abnormalities recognizable at birth, open neural tube defects, or neonatal abstinence syndrome were excluded. Deaths caused by medical termination of pregnancy and deaths occurring in the peripartum period or the first week of life were reviewed. There were 90 infants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria for neonatal encephalopathy, which led to an incidence of 1.64 per 1000 term live births (95% confidence interval, 1.30–1.98). Medical terminations of pregnancy were performed in 23 pregnancies, and if all infants were assumed to have survived and developed encephalopathy, the incidence would be 2.06 per 1000 term live births (95% confidence interval, 1.68–2.44).

None of the studies mentioned provided any information on mild encephalopathy and only focused on cases recognizable at birth or shortly thereafter (first week of life). The available data indicate that even among population-based studies there is a broad range of incidence for moderate and severe neonatal encephalopathy that spans from 1.64 to 3.8 per 1000 term births. Differences in case ascertainment and exclusion criteria may contribute to the differences, but it is unclear whether other factors may be of importance. Other considerations include population differences (eg, genetic susceptibility/resistance to hypoxia-ischemia) and access/quality of the obstetric care, assuming that at least some causes of neonatal encephalopathy are modifiable (see below). Temporal trends in the incidence of neonatal encephalopathy that may reflect population characteristics, care practices, or environmental exposures may also contribute.

A major gap in knowledge is the lack of information regarding risk factors and incidence of neonatal encephalopathy in preterm infants. The neurologic findings that are used to characterize encephalopathy pose a challenge for preterm infants compared to term counterparts. Preterm infants have systematic developmental differences in level of alertness, primitive reflexes, tone, and posture that modify the neurological examination compared to a term infant. Specifically, hypotonia is common to preterm infants and is expected for infants less than 30 weeks’ gestation,5 pupil reaction to light begins to appear at 30 weeks’ gestation but is not present consistently until approximately 32 to 35 weeks,6 and the Moro reflex displays gradual incorporation of all its components (extension and abduction of the upper extremities, followed by adduction at the shoulder) when comparing extreme, moderate, and late preterm infants.5 Neurological findings characteristic of healthy preterm infants may represent abnormalities in term infants. In addition, some neurological findings (eg, tone, level of alertness) may be influenced by common morbidities of prematurity, such as respiratory distress syndrome. Systematic evaluations of the neurological examination among preterm infants who are thought to have evidence of encephalopathy have not been performed. Even reports that focused on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in preterm infants have not addressed the neurological examination findings.7

RISK FACTORS FOR NEONATAL ENCEPHALOPATHY

Enrollment of 400 control term infants (enrolled without matching) from the Perth region population study of neonatal encephalopathy allowed comparison with cases of encephalopathy and provided insight into risk factors associated with this condition.2 Multiple variables were examined from before conception, the antepartum and intrapartum periods, and infant characteristics. Variables with the strongest association with neonatal encephalopathy (adjusted odds ratio > 5) included older maternal age (30–34 and ≥ 35 years of age), late or no antenatal care, maternal thyroid disease, severe preeclampsia, postdates (gestational age of 42 weeks), and severe growth restriction (birth weight < 3%). A wide number of other sociodemographic and antepartum variables were associated with newborn encephalopathy but with lower odds ratios. Biologically plausible pathways that culminate with encephalopathy could be postulated to incorporate many of these risk factors. For example, older maternal age, severe preeclampsia, and maternal thyroid disease could be associated with placental pathology and associated intrauterine growth restriction. The growth-restricted infant may in turn have poor tolerance of the stress of labor.

Based on these associations, the same authors postulated a number of different pathways to the development of neonatal encephalopathy.8 Risk factors present in the antepartum period support a potential two-hit hypothesis by which vulnerability of the fetus is increased secondary to the risk factors and, when combined with an intrapartum insult, may result in encephalopathy. Alternatively, a catastrophic/sentinel event during the intrapartum interval (acute abruptio placenta, ruptured uterus) may be sufficient to result in encephalopathy. A third but less-common possibility is that antepartum risk factors result in brain injury remote from the intrapartum period and result in encephalopathy.

OUTCOME OF INFANTS WITH NEONATAL ENCEPHALOPATHY

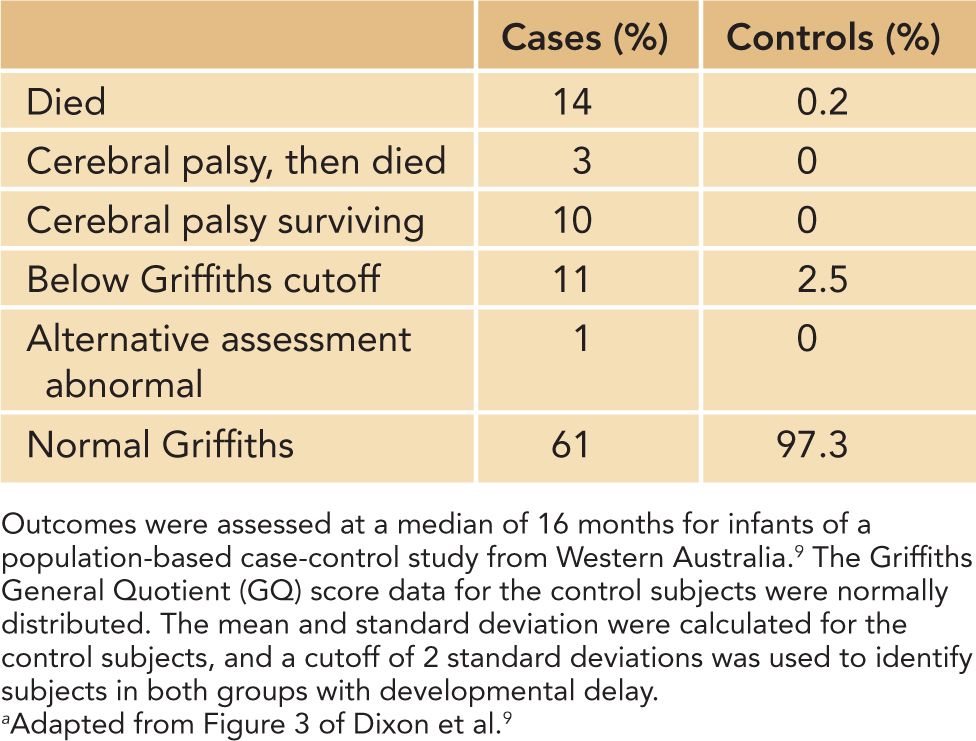

The same methodological issues that have an impact on the incidence of neonatal encephalopathy have similar relevance and importance for determining an unbiased estimate of its outcome. The largest and most comprehensive follow-up study was performed in Western Australia and included infants from the population-based incidence study from the Perth region2 but was extended9 from 1993 to 1996. This study enrolled 276 term infants with moderate and severe encephalopathy and 564 unmatched term control infants. Assessments were performed at an average age of 16 months and included the Griffiths Mental Developmental Scales and determinations of cerebral palsy. Encephalopathy was graded as moderate or severe based on Sarnat scoring.10 The results are summarized in Table 12-1; of the 276 cases of encephalopathy, 34 died prior to follow-up, and 81% of eligible infants were assessed developmentally. Of the 564 control infants, 1 infant died, and 79% were assessed developmentally. Overall, 39% of infants with encephalopathy had a poor outcome as defined by death, cerebral palsy, or a developmental delay compared with 2.7% of the control subjects. As expected among infants with encephalopathy, a poor outcome was more frequent with severe (62%) compared to moderate (25%) encephalopathy. Data provided in this report represent a group outcome and are irrespective of the cause of encephalopathy.

Table 12-1 Outcome Following Neonatal Encephalopathya

Follow-up of infants from the population study conducted in France indicated similar outcomes for infants with encephalopathy. Specifically, 27% of the infants died, and there was a 42% overall incidence of death or a severe disability at 2 years of age.4 Loss to follow-up was minimal at 4.4%. However, follow-up evaluations were not as systematic as the Western Australian study and included standard clinical and neurological evaluations until 2 years of age without formal testing of cognitive functions. Disability was ascertained from registries for the region, which included all handicapped children requiring special education. Similarly, follow-up from the Thames region of the United Kingdom reported that death or disability (cerebral palsy or other impairments) occurred in 34% of infants with neonatal encephalopathy.3 Follow-up information was obtained from the records of pediatricians; infants who were lost to follow-up per the pediatrician or were seen at less than 15 months (n = 32) were presumed to be normal for this report.

Characterization of the outcome of neonatal encephalopathy by the putative underlying etiology is a complex of issues leading to a mix of approaches in the literature. Results from Western Australia did not present defined causative groups but rather classified risk factors into preconceptional, antepartum, and intrapartum periods.9 Of note, only 4% of encephalopathy cases were associated solely with intrapartum risk factors (factors with odds ratios ≥ 3 included occipito-posterior position, maternal pyrexia, cord prolapse, shoulder dystocia, and acute intrapartum events [avulsed cord, ruptured uterus, hemorrhage, maternal seizures]). In contrast, 29% of encephalopathy cases had both antepartum risk factors and intrapartum markers, supporting the notion of the two-hit hypothesis discussed previously. Thus, almost 70% of encephalopathy cases had no evidence of intrapartum hypoxia; these results question prevalent thinking that most risk factors for newborn encephalopathy occur in the intrapartum period. This approach acknowledges the difficulty in assigning cause to an infant with encephalopathy. Consider the infant born by emergent cesarean section for a nonreassuring fetal heart pattern after a labor complicated by chorioamnionitis and fever; if this infant has poor respiratory effort and muscle tone and bradycardia at birth, requires resuscitation, has a mixed acidemia at birth (metabolic and respiratory abnormalities), and demonstrates encephalopathy in the immediate newborn period, is the etiology infection, inflammation, or hypoxia-ischemia? If infection leads to inflammation, which in turn increases the vulnerability of the fetus to hypoxia-ischemia during labor, what is the correct assignment of causation? Based on these considerations, many investigators have made cogent arguments for using the term neonatal encephalopathy and avoiding hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.11

In contrast to the approach discussed, some follow-up reports have attempted to assign a cause for encephalopathy.4 For example, in the population study conducted in France, the most common etiology of encephalopathy was perinatal hypoxia-ischemia occurring in the intrapartum period.4 This was causative in 52% of encephalopathy cases (isolated in 77%, associated with another diagnosis in 17%, and with intrauterine growth retardation [IUGR] in 6%). Other etiologies included infection, intracranial hemorrhage, structural brain defects, genetic syndromes, inborn errors of metabolism, and other poorly defined causes.

RATIONALE FOR ESTABLISHING THE ETIOLOGY OF NEWBORN ENCEPHALOPATHY

Assignment of cause for cases of encephalopathy is controversial, and much of this stems from the challenges of making a diagnosis of perinatal asphyxia. Given the last concerns, is it important to determine the underlying etiology for cases of encephalopathy? Determination of etiology is critical only if there are potential modifiable causes of encephalopathy. There are many causes of newborn encephalopathy (Table 12-2), and some have specific treatments that alter outcome. The importance of establishing a cause for encephalopathy is best appreciated for infants with encephalopathy presumed to be of hypoxic-ischemic origin because there is an available therapy. Hypothermia is a proven therapy for late preterm and term infants with this condition, and its use is associated with a reduction in the composite outcome of death or disability assessed at 18–22 months.12 The clinical evidence to support the efficacy of therapeutic hypothermia culminated approximately 20 years of investigative work spanning the original laboratory observations in adult rodents,13 confirmation of similar observations in perinatal animals,14–16 and ultimately pilot studies followed by efficacy trials as summarized in a recent meta-analysis.17

Table 12-2 Causes of Newborn Encephalopathy

Hypoxia-ischemia

Stroke

Sepsis/inflammatory response syndrome

Intracranial hemorrhage

Inborn errors of metabolism

Structural brain abnormalities

Bilirubin toxicity

Drug effects

Estimates for the number of infants who could be potential candidates for therapeutic hypothermia can be derived from available statistics. If one uses 4 million births per year in the United States and assumes that 88% are greater than or equal to 36 weeks’ gestation, there would be 3.52 million births. A population-based incidence of newborn encephalopathy in the United States is unknown, but using the range available in the literature (1.6–3.8/1000 term births2,4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree