Warming Procedures

Robert Hickey

Allan de Caen

Introduction

Hypothermia is defined as a core temperature below 35°C (95°F). The most common cause of hypothermia in the pediatric population is exposure to cold environments (cold water drowning, “found outside” in winter, etc.). Children, especially very young children, are relatively susceptible to hypothermia because of their large surface area to mass ratio, immature judgment, and lack of behavioral defense mechanisms. Less commonly, chronic disease, malnourishment, fatigue, and intoxication are important risk factors in children.

Anatomy and Physiology

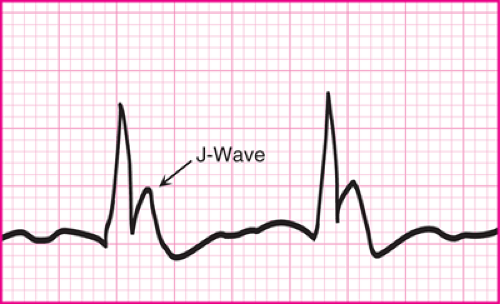

Hypothermia can be categorized as mild (core body temperature 32°C to 35°C [89.6°F to 95°F]), moderate (28°C to 31°C [82.4°F to 87.8°F]), or severe (less than 28°C [82.4°F]). Clinical deterioration roughly parallels these divisions. Patients with mild hypothermia have intact thermoregulatory responses (vasoconstriction, shivering) and mild alterations in muscle control, coordination, and mental status. Moderate hypothermia is accompanied by a decreased level of consciousness, ineffective or absent shivering, and dysrhythmias, often heralded by the appearance of a J wave on EKG (Fig. 131.1). Severe hypothermia is accompanied by loss of consciousness, absent shivering, and ventricular fibrillation or asystole.

Although hypothermia can cause death, it also has a powerful neuroprotective effect when it occurs rapidly. Thus, in contrast to normothermic arrest, hypothermic arrest can be successfully reversed even if the arrest is prolonged (1 to 2 hours). Children with profound accidental hypothermia and even apparent clinical death have been successfully resuscitated with good neurologic outcomes (1,2,3), and patients with rectal temperatures as low as 16.0°C have survived with little or no demonstrable morbidity. Thus, the techniques described in this chapter are truly life-saving techniques that pediatricians and emergency medicine providers should be prepared to institute in appropriate conditions.

Warming techniques can be categorized as passive or active. Passive techniques encourage endogenous generation of heat and are the treatment of choice for patients who can shiver. Passive techniques include encouraging exercise and providing warm clothes, insulation (blankets), and food (Fig. 131.2) (4,5,6). Active techniques include exogenous application of heat to external organs (skin) or internal organs. Common procedures are listed in Table 131.1. One important complication of active external warming is “afterdrop.” Afterdrop is a fall in core temperature caused, in part, by vasodilation and improved circulation to cold extremities, with return of cooled blood to the body’s core. Thus, some experts recommend limiting active external warming to the trunk and avoiding it altogether in patients with intact shivering (external warming can suppress shivering and may be less efficient than shivering). However, forced air warmers can be very effective in children and are less likely to cause afterdrop than the other techniques. Forced air warmers use circulating warm air to heat the body by convection (heat transfer by a moving body of gas or liquid). Another major advantage of forced air warmers is that they are commonly used in operating rooms and can be easily transported to the emergency department (ED) for emergent use. Thus, forced air warmers are increasingly used for even unstable patients. Indeed, forced air warmers have been used successfully to warm children with severe hypothermia and cardiac arrest (Fig. 131.3) (3).

Active internal warming requires establishing access to an internal body cavity. Many of the necessary procedures are described elsewhere in this textbook. Closed thoracic lavage and peritoneal lavage require chest tube and peritoneal catheter

placement and are attractive techniques for utilization in the ED because pediatric emergency care providers are relatively experienced in them (Chapters 27 and 29). Gastric lavage and bladder lavage have limited effectiveness because of the small surface area of these organs. Likewise, warmed intravenous fluid and warmed inhalation therapy have modest heat exchange and are best considered techniques to prevent additional heat loss rather than techniques to provide heat. The most effective therapy, and the preferred therapy for severely hypothermic patients with nonperfusing cardiac rhythms, is extracorporeal support. One series from an experienced team reports long-term survival following extracorporeal bypass in 15 of 32 patients presenting with a mean core temperature of 21.8°C and a mean time between discovery and bypass of 141 minutes (7). The major disadvantage of extracorporeal support is the need for specialized equipment and trained personnel.

placement and are attractive techniques for utilization in the ED because pediatric emergency care providers are relatively experienced in them (Chapters 27 and 29). Gastric lavage and bladder lavage have limited effectiveness because of the small surface area of these organs. Likewise, warmed intravenous fluid and warmed inhalation therapy have modest heat exchange and are best considered techniques to prevent additional heat loss rather than techniques to provide heat. The most effective therapy, and the preferred therapy for severely hypothermic patients with nonperfusing cardiac rhythms, is extracorporeal support. One series from an experienced team reports long-term survival following extracorporeal bypass in 15 of 32 patients presenting with a mean core temperature of 21.8°C and a mean time between discovery and bypass of 141 minutes (7). The major disadvantage of extracorporeal support is the need for specialized equipment and trained personnel.

TABLE 131.1 Common Warming Procedures | |

|---|---|

|

Indications

Warming techniques should be considered in the context of the patient’s presenting signs and symptoms, the requirement for other resuscitation therapies, and the availability of resources. Complicating factors include (a) afterdrop causing a transient lowering of core temperature; (b) susceptibility of the heart to fibrillate at core temperatures below 28°C, especially when “handled roughly” (by chest compressions, intubation, etc.); (c) limited efficacy of drugs and electrical defibrillation below 30°C; and (d) difficulty of detecting cardiac activity and respiratory efforts in profoundly cold and depressed patients. The American Heart Association algorithm attempting to integrate these factors is shown in Figure 131.4 (8). Extensive reviews incorporating treatment algorithms have been published (9,10).

Equipment

All rewarming techniques

Core temperature monitor

Indwelling rectal thermometer probe

Esophageal thermometer

Continuous tympanic membrane thermometer

Heated cascade nebulizer or ventilator with heating cascade

Active external rewarming

Radiant warmer

Warmed blankets or forced air rewarmer

Active internal rewarming

Rapid intravenous fluid infuser

See equipment lists for peritoneal lavage (Chapter 27) and thoracostomy tube placement (Chapter 29).

Procedures

Active External Rewarming

Heating Blankets

A variety of heating blankets exist (electrical, circulating water, resistive). Heating blankets work by direct, contact-to-contact heat transference (conduction). Blankets should be placed on top of the patient to maximize heat transfer. Placement of heating blankets under the patient is less effective because compression of the dependent vascular beds attenuates heat transfer (6), and 90% of ongoing losses are lost from nondependent areas of the body (5). Accordingly, when warming blankets are placed on top of the patient, there is little difference in efficacy between the various blankets (11,12), and warming rates may be comparable to convective warming devices (13). The need for ongoing patient resuscitation may limit the effectiveness of this technique due to the need to uncover the patient.

Forced Air (Fig. 131.3)

Several equivalent forced air (convection) warming devices are now available (14). The devices are portable and easily transported from the intensive care unit, operating room, or recovery suite to the ED. Application is simple, but the blanket does limit access to the patient. Pediatric case series have shown this technique to be effective even in patients with profound hypothermia (temperature less than 28°C) as long as intact circulation is present (3). Warming rates in adults have been documented as being as slow as 1°C to 2°C per hour (15,16), but pediatric case series have documented warming rates as fast as 4.2°C per hour (3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree