Vulvovaginal Problems in the Prepubertal Child

S. Jean Emans

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvovaginitis is a common gynecologic problem in prepubertal girls. Vulvar inflammation, termed vulvitis, may occur alone or may be accompanied by a vaginal inflammation, vaginitis. A child may acquire a primary vaginal infection, and the discharge may cause maceration of the vulva and/or secondary vulvitis. The prepubertal child is particularly susceptible to vulvar and vaginal infections because of the physiology of their genital tract. In the newborn period, the vagina is well estrogenized from maternal hormones. For several months to several years beyond the newborn period, the infant has fluctuating gonadotropin levels, which can result in stimulation of the ovaries to produce low levels of estrogen. As the estrogen levels wane, the hymen becomes thin and the vagina atrophic with a pH of 6.5 to 7.5. The prepubertal child is thus susceptible to both nonspecific and specific vaginal infections and a variety of vulvar skin abnormalities (dermatoses) (Table 4-1 and see Chapter 5) (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10). Contributing factors appear to be lack of estrogenization, the proximity of the vagina to the anus, the lack of protective hair and labial fat pads, and poor hygiene. The vulvar skin is susceptible to irritation and is easily traumatized by chemicals, soaps, medications, and clothing. Vulvar itching is a common complaint and frequently does not have a specific etiology (11). Nonabsorbent nylon underpants, nylon tights, nylon bathing suits, close-fitting blue jeans, and ballet leotards may result in maceration and infection, particularly in hot weather. Little girls who are overweight are particularly likely to experience these symptoms. The vulvar irritation of the child with vaginitis may appear similar to the diaper dermatitis seen in infants. Bubble baths and harsh soaps may cause vulvitis and a secondary vaginitis. Girls typically urinate on the toilet with their knees together, increasing the possibility that urine will reflux into the vagina and then dribble out later.

Normal Vaginal Flora

Several studies have provided information on the “normal flora” of the vagina in prepubertal girls and premenarcheal girls, but most have limitations, including small sample size, recent antibiotic use in controls (often having ear, nose, and throat procedures), and inclusion of both prepubertal and (estrogenized) pubertal girls in the same study (2,8,12,13,14,15). In a study of girls with vaginitis, Paradise and colleagues (2,15) obtained vaginal specimens from 52 controls who were premenarcheal girls without genitourinary signs or symptoms (Table 4-2); 11 of 40 controls specifically cultured for Bacteroides species (B. bivius, B. fragilis, B. melaninogenicus) were positive (2). Bacteroides species were commonly found in the symptomatic subjects with vulvovaginitis (13 of 40 positive). Gardner (13) studied a group of 77 girls, 3 to 10 years of age, who were undergoing minor nongynecologic procedures under general anesthesia. She defined normal flora as lactobacilli, Staphylococcus epidermidis, enteric organisms (Streptococcus faecalis, Klebsiella species, Proteus species, Pseudomonas species), and viridans species of streptococci other than Streptococcus milleri. Additional isolates from the control group included Escherichia coli (two girls), Streptococcus pneumoniae (five), Staphylococcus aureus (four), Streptococcus milleri (one), and Gardnerella vaginalis (three). No isolates of Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, or mycoplasmas were identified. Another study of normal vaginal flora found that the most common aerobic organisms were Staphylococcus epidermidis, enterococci, E. coli, lactobacilli, and Streptococcus viridans (14). The anaerobes included Peptococcus species, Peptostreptococcus species, Veillonella parvula, Eubacterium species, Propionibacterium species, and Bacteroides species. Other organisms found in asymptomatic girls included Proteus mirabilis (3.2%), Pseudomonas species (6.5%), and Candida albicans (3.2%). A study comparing girls with vulvovaginitis with controls found similar microbiologic flora, including mixed anaerobes, diphtheroids, coagulase-negative staphylococci, and E. coli (8). Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic streptococci were more common among girls with vaginitis than controls, as was Proteus species, but the latter did not reach statistical significance. Low percentages of H. influenzae (4%) and group B streptococci (2%) were seen in both groups. In this study, Pseudomonas species (2%), Streptococcus milleri (4%), and Klebsiella species (2%) were isolated only from the girls with vaginitis.

Etiology of Vulvovaginitis

Nonspecific Vaginitis

The spectrum of diagnoses causing vulvovaginal symptoms is quite broad (see Table 4-1). “Nonspecific” vulvovaginitis accounts for 25% to 75% of the cases of vulvovaginitis seen in referral centers (2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10). The vaginal culture from girls with vaginitis typically grows normal flora (lactobacilli, diphtheroids, Staphylococcus epidermidis, or α-streptococci) or gram-negative enteric organisms (usually E. coli). Thus, the pathogenesis and associated alteration in vaginal flora have not been well defined, but the absolute number of colonies of fecal aerobes or an overpopulation with anaerobes may contribute to the symptoms of odor and discharge. Gerstner and colleagues (14) found Candida, Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, and Bacteroides species more commonly in girls with vaginal discharge and/or vulvovaginitis than in asymptomatic girls. In contrast, Paradise and colleagues (2) found a similar prevalence of Bacteroides species in controls and girls with vaginitis. Similarly, E. coli may be a marker for poor hygiene and is found in both controls and girls with vaginitis. In a study at our hospital, 47% of 3- to 10-year-old girls with nonspecific vaginitis had E. coli on culture (3). Another study

(14) found that 23% of asymptomatic girls had E. coli in the vagina, compared with 36% of girls with vaginitis. Paradise and colleagues (2) isolated E. coli from 7 of 54 girls with vaginitis and 4 of 52 controls, and Jaquiery and colleagues (8) found E. coli in 30% of girls with vaginitis and 34% of controls. The role of bowel flora in the occurrence and/or persistence of symptoms needs further research. Children susceptible to recurrent vulvovaginitis may have other factors that promote adherence of bacteria to epithelial cells. Of note, pinworms appear to be a major contributor to nonspecific infections in some populations. In a British study, 32% of girls with vulvovaginitis had pinworms detected (6).

(14) found that 23% of asymptomatic girls had E. coli in the vagina, compared with 36% of girls with vaginitis. Paradise and colleagues (2) isolated E. coli from 7 of 54 girls with vaginitis and 4 of 52 controls, and Jaquiery and colleagues (8) found E. coli in 30% of girls with vaginitis and 34% of controls. The role of bowel flora in the occurrence and/or persistence of symptoms needs further research. Children susceptible to recurrent vulvovaginitis may have other factors that promote adherence of bacteria to epithelial cells. Of note, pinworms appear to be a major contributor to nonspecific infections in some populations. In a British study, 32% of girls with vulvovaginitis had pinworms detected (6).

Table 4-1 Etiology of Vulvovaginal Symptoms in the Prepubertal Child | |

|---|---|

|

True vulvovaginitis should not be confused with physiologic pubertal discharge. Newborns and pubescent girls often have copious secretions from the effect of estrogen on the vaginal mucosa. In newborns, maternal estrogen is primarily responsible for the discharge, which typically disappears within a few weeks after birth.

Specific Infections with Respiratory or Enteric Pathogens

The specific infections that occur in the prepubertal child are caused by respiratory, enteric, or sexually transmitted pathogens. The most common respiratory pathogen is Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci), which is isolated from 6% to 20% of girls with vulvovaginitis (6,7,8,9,10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23). Vaginal S. pyogenes infections may be associated with nasopharyngeal, perianal, or skin infections. Although throat cultures from 28% to 92% of girls with S. pyogenes vaginitis are positive, only 25% to 30% have symptoms of pharyngitis (19,20). Scarlet fever and guttate psoriasis can also be associated with streptococcal vaginitis. In one New England state, perineal S. pyogenes infections peaked in the late winter and early spring (21). Symptoms may include pruritus, dysuria, pain, and vaginal or rectal bleeding. The vulva and perianal areas often have a distinctive bright red (“beefy red”) inflamed appearance (see Chapter 5, Fig. 5-47). Recurrent vaginitis may be associated with persistent pharyngeal carriage (22).

Table 4-2 Two Studies of Microbiology of the Vagina | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Less commonly, vaginitis is associated with H. influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Branhamella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis (2,3,6,24,25). These organisms may also be found in asymptomatic girls, and girls with symptoms often improve with hygiene alone while awaiting the culture results. For example, Paradise and colleagues (2) reported that the few girls in their study with vulvovaginal symptoms and positive cultures for coagulase-positive Staphylococcus or H. influenzae (type b and nontypeable) often had other etiologies for their vaginitis and typically resolved without antibiotic therapy. In addition, H. influenzae was more commonly isolated 20 years ago than currently. Staphylococcus aureus can be associated

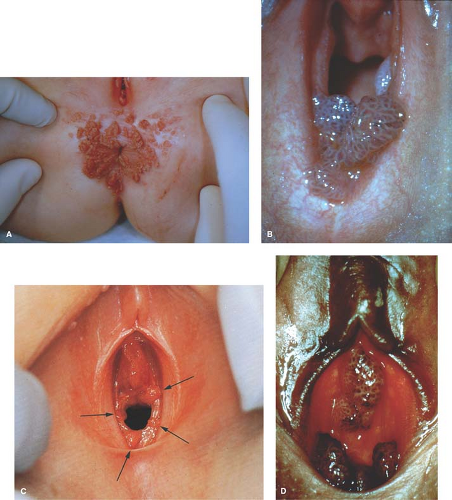

with vaginitis and impetiginous lesions on the vulva and the buttocks. Shigella infection can result in a mucopurulent, sometimes bloody vaginal discharge. In only one-fourth of cases, the discharge occurs in association with an episode of diarrhea (26). Between 70% and 90% of Shigella vaginitis is caused by Shigella flexneri (26,27,28). Yersinia enterocolitica has also been reported to be associated with vaginitis (29); whether other enteric pathogens play a role is not known. Although Candida vulvovaginitis is common in pubertal, estrogenized girls and infants in diapers (Fig. 4-1), it is uncommon in prepubertal children unless the girl has recently finished a course of antibiotics, has diabetes mellitus, is immunosuppressed, or has other risk factors. Candida appears to be present in the normal vaginal flora of 3% to 4% of girls.

with vaginitis and impetiginous lesions on the vulva and the buttocks. Shigella infection can result in a mucopurulent, sometimes bloody vaginal discharge. In only one-fourth of cases, the discharge occurs in association with an episode of diarrhea (26). Between 70% and 90% of Shigella vaginitis is caused by Shigella flexneri (26,27,28). Yersinia enterocolitica has also been reported to be associated with vaginitis (29); whether other enteric pathogens play a role is not known. Although Candida vulvovaginitis is common in pubertal, estrogenized girls and infants in diapers (Fig. 4-1), it is uncommon in prepubertal children unless the girl has recently finished a course of antibiotics, has diabetes mellitus, is immunosuppressed, or has other risk factors. Candida appears to be present in the normal vaginal flora of 3% to 4% of girls.

Infections with Sexually Associated Pathogens

Sexually acquired vulvovaginal infections occurring in the prepubertal child include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas, herpes simplex, and human papillomavirus (condyloma acuminatum) (these infections are also discussed in Chapters 5, 17, 18, and 30) (30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39). Gonococcal infection in the prepubertal child usually causes a green purulent vaginal discharge; occasionally the discharge is mucoid. Rarely the infection is asymptomatic. Confirmatory tests are crucial in prepubertal girls whose vaginal culture (preferred for suspected gonococcal infections) or vaginal or urine nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) is reported to be positive for N. gonorrhoeae (34) (see Chapter 1, p. 8). The prevalence of N. gonorrhoeae in girls with vaginitis varies from 0% to 26%. Siblings of individuals with known gonococcal infections are also at risk of infection and should be tested. The perpetrator is often a family member who is identified only by testing samples taken from the entire family. All children with N. gonorrhoeae vaginitis should be reported to child protection agencies.

Chlamydia trachomatis may be acquired from sexual contact or from perinatal maternal–infant transmission (31,32,40,41,42,43). Schachter and associates (40) found that 14% of infants born to Chlamydia-positive mothers had vaginal/rectal colonization; none of these infants still had positive cultures at 12 months of age. Bell and colleagues (41) reported that among 120 infants born vaginally to infected women, 22% had positive cultures from the conjunctiva and 25% from the pharynx in the first month of life. Positive rectal and vaginal cultures were obtained during the third and fourth months of life. In a study of 22 infants in Seattle, positive rectal and vaginal cultures were not seen beyond 383 and 372 days, respectively, but positive cultures from the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and conjunctiva persisted up to 866 days (43). Ocular infection may persist for 3 to 6 years (44). However, because the majority of girls will have been treated for other infections by the age of 2 or 3 years with antibiotics to which Chlamydia is sensitive (e.g., erythromycin, azithromycin), persistence from maternal–infant transmission becomes an unlikely explanation in most girls. Girls older than age 2 to 3 are thus likely to have acquired a Chlamydia infection from sexual contact. In a study of sexually abused and control girls, Ingram and associates (31) reported that 10 of 124 sexually abused girls and 0 of 90 control girls had a positive introital culture for C. trachomatis. In another study of 1538 children evaluated for possible sexual abuse, Ingram and colleagues found Chlamydia infections in 1.2% (37). A more recent study of 485 girls evaluated for sexual abuse found that 3.1% were positive for Chlamydia and 3.3% had N. gonorrhoeae (38). As in adolescents, C. trachomatis can occur as a coexisting infection in girls with N. gonorrhoeae (45). How frequently C. trachomatis is responsible for signs of vaginitis is a subject of controversy, with reports of 1 of 6 girls and 6 of 17 girls with a positive Chlamydia test also having vaginitis (34,37). (See also Chapter 1, p. 8 for caveats related to lower sensitivity of culture versus NAATs for detection of C. trachomatis in children and the need to retain the sample and confirm with a second test [46].)

Herpes simplex type 1 (oral-labial herpes) may cause vulvar infections in young girls from self-inoculation of the virus from oral lesions or from sexual contact. Herpes simplex type 2 infections beyond the perinatal period strongly suggest sexual abuse. In a study of six cases of genital herpes (five type 1 and one type 2), infection resulted from sexual abuse in four of six patients (47). Recurrent lesions may occur with either type of herpes but are more likely with type 2. Varicella-zoster infections in the genital area have been confused with herpes simplex (48). Condylomata acuminata (venereal warts) are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), usually HPV subtypes 6 or type 11, and can occur in the genital and perianal area (Fig. 4-2) (see also Chapters 5, 20, and 30).

Trichomonas vaginalis can be transmitted from the mother to the child at birth and rarely can cause urethritis and vaginitis, which usually resolves spontaneously with the waning of estrogen levels. Occasionally, persistent symptoms require treatment (39). This pathogen is rarely seen in the prepubertal child because the unestrogenized vagina is relatively resistant to infection. It occurs primarily in the sexually active teenager (see Chapter 17). Although Trichomonas can theoretically be spread by wet towels and washcloths, it is primarily a sexually transmitted infection.

The role of G. vaginalis in causing vaginitis in the child has been controversial (10,49,50). Bartley and co-workers (49) found that the isolation of G. vaginalis from the vaginas of prepubertal girls appeared to be more likely in sexually abused girls (14.6%) than in control subjects (4.2%) or in patients with genitourinary complaints (4.2%). However, they did not find any association of this organism with vaginal erythema or discharge. In contrast, Ingram and associates (50) found G. vaginalis in the vaginal cultures of 5.3% of 191 sexually abused girls, 4.9% of 144 girls evaluated for possible sexual abuse, and 6.4% of

control girls (daughters of friends of the authors). The isolated finding of G. vaginalis on vaginal culture should not be confused with a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Bacterial vaginosis is characterized by an alteration of the bacterial flora with the presence of increased concentrations of G. vaginalis and anaerobes and in adolescents is characterized by a high vaginal pH and clue cells (see Chapter 17). Bacterial vaginosis has been rarely reported in girls who presented with vaginal odor after an episode of rape; the diagnosis was made by the observation of clue cells on microscopic examination of the discharge and the presence of a characteristic amine (fishy) odor on the “whiff” test (see Chapter 17).

control girls (daughters of friends of the authors). The isolated finding of G. vaginalis on vaginal culture should not be confused with a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Bacterial vaginosis is characterized by an alteration of the bacterial flora with the presence of increased concentrations of G. vaginalis and anaerobes and in adolescents is characterized by a high vaginal pH and clue cells (see Chapter 17). Bacterial vaginosis has been rarely reported in girls who presented with vaginal odor after an episode of rape; the diagnosis was made by the observation of clue cells on microscopic examination of the discharge and the presence of a characteristic amine (fishy) odor on the “whiff” test (see Chapter 17).

Other Causes of Vulvovaginal Complaints

Other causes of vulvovaginal complaints include vaginal foreign bodies; vaginal and cervical polyps and tumors; cavernous lymphangioma; urethral prolapse; systemic illnesses such as measles, chickenpox (48), scarlet fever, mononucleosis, Crohn disease, Kawasaki disease (51), or histiocytosis; anomalies such as double vagina with a fistula, pelvic abscess or fistula, or ectopic ureter; and vulvar skin diseases such as seborrhea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, lichen sclerosus, scabies, contact dermatitis, impetigo, or autoimmune bullous diseases (see Table 4-1, Chapter 5 for photographs of these conditions, and Chapter 17).

Zinc deficiency from insufficient intake (52), urinary loss, or malabsorption (acrodermatitis enteropathica) can result in vulvar dermatitis. Seborrheic dermatitis is associated with seborrhea in other parts of the body; fissures within the folds of the labia can lead to bleeding. Both psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis can become secondarily infected. Psoriasis in the groin may also be mistaken for diaper dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis usually occurs in other parts of the body as well as the vulva; vulvar lesions are pruritic, dry, papular, scaly patches. Bullous pemphigoid occasionally occurs in young children with recurrent ulcers and erosions. Chronic bullous disease of childhood is rare and is associated with pruritic and burning vesicles and bullae on the genitals, face, trunk, and extremities. Vesicular lesions in the perineum secondary to nickel allergy from an enuresis alarm can occur (53

Zinc deficiency from insufficient intake (52), urinary loss, or malabsorption (acrodermatitis enteropathica) can result in vulvar dermatitis. Seborrheic dermatitis is associated with seborrhea in other parts of the body; fissures within the folds of the labia can lead to bleeding. Both psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis can become secondarily infected. Psoriasis in the groin may also be mistaken for diaper dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis usually occurs in other parts of the body as well as the vulva; vulvar lesions are pruritic, dry, papular, scaly patches. Bullous pemphigoid occasionally occurs in young children with recurrent ulcers and erosions. Chronic bullous disease of childhood is rare and is associated with pruritic and burning vesicles and bullae on the genitals, face, trunk, and extremities. Vesicular lesions in the perineum secondary to nickel allergy from an enuresis alarm can occur (53

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree