Pediatric Urology

Craig A. Peters

Fern G. Campbell

This chapter addresses urologic issues in young girls and adolescents. Many urologic issues overlap with gynecologic issues, and thus some abnormalities are discussed in this chapter from a urologist’s point of view, in addition to the discussion in other chapters. Presenting symptoms, evaluation, and the differential diagnosis of common and uncommon problems are discussed including incontinence, dysuria, urethral pain, pelvic pain, hematuria, dysfunctional voiding, urinary tract infections, renal colic, renal and perineal masses, and congenital anomalies of the urinary tract. A collaborative partnership between pediatric urologists and gynecologists has yielded discussions and understanding of perspectives in addressing the clinical care of girls and young women.

Presenting Symptoms: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis

Incontinence

Incontinence is a common complaint in girls, with a predominantly social and emotional rather than medical impact. The potential for underlying severe neurologic and structural problems, however, cannot be ignored. Efficient screening for risk factors is the key to identifying the few patients with severe problems, while focusing therapy, as well as minimizing invasive evaluation, is the key for the remainder. Regular continence should develop in the third year of life in most children, with nighttime control developing more slowly. The range of normal is very wide and often culturally and socially influenced. The parents may be hesitant to bring children for evaluation, being unsure as to what is considered normal. Others may demand development of urinary control, often in response to childcare and school requirements.

Incontinence is the involuntary loss of urinary control and may have several forms. Evaluation of the child with incontinence is founded on establishing the pattern of wetting as described in Table 15-1, as well as the frequency of occurrence, the pattern over time, and any associated external factors.

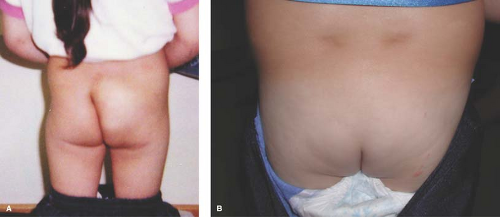

Physical examination is rarely revealing of any abnormality, but when it is, it usually suggests a major problem. The focus should be on any evidence of a neurologic anomaly as evidenced by an abnormal sacral spine or lower extremities (Fig. 15-1). Since the sacral nerve roots control both the perineum and the feet, abnormalities of the latter may suggest neurologic abnormalities of the bladder and bowel. An asymmetric gluteal cleft, a patch of hair, a dermovascular malformation, or a sacral mass all point to a potential neurologic basis of incontinence (1,2). Examination of the perineum is important to exclude the rare condition of female epispadias, which is usually associated with total incontinence (Fig. 15-2). On occasion, one may be able to identify the ectopic ureteral orifice in the perineum leaking drops of urine (Fig. 15-3). Palpating the abdomen can identify a distended bladder, often easily noted and with a child who claims she does not feel full. Similarly, the full doughy sensation of an abdomen full of stool will suggest the association with constipation. It is also useful to observe the child’s affect during the discussion about incontinence, as it will suggest her reaction to it. This can vary from total indifference to significant embarrassment. The interaction between the child and the parent is also important to assess and may reveal excessive parental attention and discipline, which may require additional advice or coun-seling.

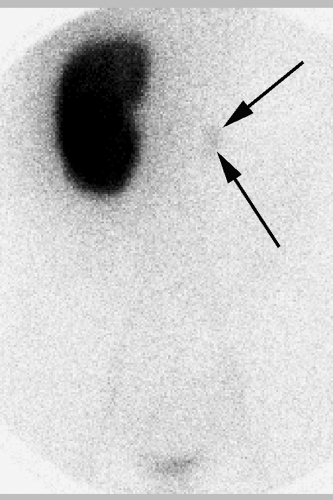

The presumed form of incontinence can usually be deduced from the history and physical examination. Further testing should be guided by recognition of what is likely to be demonstrated, as well as the therapeutic options available for those possible conditions. The child with voiding postponement with no signs of neurologic abnormality can often be treated with no testing. However, many clinicians decide to obtain a urinalysis and urine culture as part of the evaluation. A bladder ultrasound demonstrating that the child has a significant postvoid residual volume even when she is convinced she has emptied her bladder can confirm the diagnosis and also serves as an important teaching tool for both parent and child. It may also demonstrate bladder wall thickening, which is a frequent occurrence in these children (3). This is confirmatory and seldom suggests, in itself, a more complex underlying problem. In children with infection, a renal ultrasound is useful in ruling out any upper urinary tract pathology and is often reassuring to parents as well. Urodynamic studies, which are invariably invasive and may even aggravate symptoms, are seldom of value in these children. A simple urinary flow rate may help to identify an intermittent flow pattern. The child with infection and incontinence may need a cystogram to rule out reflux, and this may be used to assess bladder function. Urodynamic evaluation should be reserved for children with a clear suspicion of neurologic dysfunction, with any evidence of upper tract abnormality such as hydronephrosis, or in whom all measures have not produced any improvement in symptoms (4). Renal imaging with an intravenous pyelogram (IVP), magnetic resonance (MR) urography, or computed tomography (CT) scan is rarely indicated, and then in the unusual circumstance of a possible ectopic ureter. In those situations, an ultrasound may have demonstrated hydronephrosis of an upper pole, but may also be normal. If there is a strong suspicion based on history of examination, an IVP will often reveal the ectopic ureter, usually from an upper pole moiety (Fig. 15-4). Rarely a CT, MR urogram, or technetium-99m dimercapto succinic acid (DMSA) scan will be needed to detect an occult duplex system or the small dysplastic renal unit in the child with constant wetting and an apparent solitary kidney (5) (Fig. 15-5). Cystoscopy is rarely indicated in the evaluation of the incontinent child.

Dysuria

Pain with urination or immediately afterwards is usually due to infection of the bladder, but may also be due to dysfunctional

voiding patterns (Table 15-2). This is a widely variable complaint that occurs at all ages. Dysuria is not always due to infection, which carries several significant implications and therefore infection must be documented carefully. Patients are often given antibiotics without appropriate testing, creating a confusing picture and clouding the decision-making process regarding further evaluation. In the patient with dysuria it should be determined if this occurs with every void or only after extreme delays in voiding. Is the pain relieved with voiding or actually aggravated? What was the appearance of the urine at the time of the episode? Was blood or red urine seen? Was the urine cloudy or foul smelling? All of which would point toward infection. Was there associated abdominal flank or back pain, as well as fever? Voiding habits should be determined. The adolescent should be questioned about sexual activity, vaginal symptoms, and pelvic pain.

voiding patterns (Table 15-2). This is a widely variable complaint that occurs at all ages. Dysuria is not always due to infection, which carries several significant implications and therefore infection must be documented carefully. Patients are often given antibiotics without appropriate testing, creating a confusing picture and clouding the decision-making process regarding further evaluation. In the patient with dysuria it should be determined if this occurs with every void or only after extreme delays in voiding. Is the pain relieved with voiding or actually aggravated? What was the appearance of the urine at the time of the episode? Was blood or red urine seen? Was the urine cloudy or foul smelling? All of which would point toward infection. Was there associated abdominal flank or back pain, as well as fever? Voiding habits should be determined. The adolescent should be questioned about sexual activity, vaginal symptoms, and pelvic pain.

Table 15-1 Types of Incontinence | |

|---|---|

|

Figure 15-3. Ectopic ureteral orifice in the perineum of a child with constant wetting. The angiocatheter is inserted into the orifice, which can be seen to drain drops of urine. |

Evaluation of the child should begin with a urinalysis and urine culture. Physical examination should assess any perineal lesions, bleeding, or discharge. The same assessment as for incontinence should be considered, as many patients with voiding dysfunction will have pain, with or without infection. Depending on the degree of discomfort and the likelihood of infection, empiric therapy may be started, but the quality of the urine culture must be considered. If it is contaminated and antibiotics have been started, it is almost impossible to obtain an accurate culture. If infection is present, further evaluation will depend on associated symptoms and age of the child. If the culture is negative, the urinalysis will guide therapy. If hematuria is present, imaging is essential to rule out neoplastic, structural, or calcific conditions, as discussed below. If pyuria alone is present one should consider Chlamydia infection in the sexually active adolescent girl (see Chapters 17 and 18), the rare possibility of

an occult inflammatory condition such as tuberculosis, or infection with a fastidious organism such as Ureaplasma. Further cultures, imaging, or empiric therapy are used as suggested by the context. If the urinalysis is clear, dysuria is likely due to dysfunctional voiding. If recent in onset, reassurance and instruction are usually satisfactory. If chronic, more intensive behavioral therapy as described below is needed, often with anticholinergic medications.

an occult inflammatory condition such as tuberculosis, or infection with a fastidious organism such as Ureaplasma. Further cultures, imaging, or empiric therapy are used as suggested by the context. If the urinalysis is clear, dysuria is likely due to dysfunctional voiding. If recent in onset, reassurance and instruction are usually satisfactory. If chronic, more intensive behavioral therapy as described below is needed, often with anticholinergic medications.

Table 15-2 Differential Diagnosis of Dysuria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acutely symptomatic dysuria or pelvic pain may be debilitating, and an acute inflammatory or obstructive process should be ruled out by renal and bladder ultrasound. If normal, use of antispasmodic anticholinergics will usually relieve the symptoms. Pyridium (phenazopyridine) may occasionally help as well.

Endometriosis (see Chapter 13) can cause irritative bladder symptoms, although it is often difficult to detect direct vesical involvement. Endometriosis is commonly identified on the bladder peritoneum in the anterior cul-de-sac and can cause frequent urination and pain with urination. In a patient with known endometriosis and persistent dysuria, a search for intra-vesical involvement is appropriate, although rarely fruitful (6). In the absence of documented involvement and with appropriate gynecologic therapy, symptomatic treatment of the dysuria is the best option.

Interstitial cystitis (IC), also referred to as painful bladder syndrome (PBS), is a possible cause of dysuria in the adolescent, although the diagnosis is very problematic and controversial. There have been many reports of IC in teens and younger children, although it remains a poorly defined entity, even in adults, and is a diagnosis of exclusion (7,8,9,10). Therapy is also limited.

Hematuria

Blood in the urine is one of the most disturbing symptoms, and while it may signal severe pathology, it is often due to infection and readily managed (Table 15-3). In girls the occurrence of gross, visible blood is usually noted in the toilet bowl or the diaper, so there is little ability to recognize when in the voiding cycle it might have occurred, as can be done with males. It is important to make sure the blood is not menstrual or vaginal bleeding. Indeed, it may be assumed to be so, inappropriately. Associated symptoms are important, including dysuria or abdominal or flank pain. Presence of a recent viral illness may suggest immunologic renal bleeding, as might a recent streptococcal infection. Prior trauma, even relatively mild, may suggest upper tract structural bleeding. Blood pressure, urinalysis, and culture are essential. It is important to determine whether the bleeeding is associated with pyuria, casts of red cells, large number of crystals, or increased urine calcium/creatinine ratio. It is important to determine whether the bleeding is associated with pyuria, casts of red cells, or large numbers of crystals. Crystalluria, per se, is not pathologic and occurs frequently in children, but it serves to focus attention on renal stone disease. An experienced observer with a phase contrast microscope can detect distorted red blood cells (RBCs) associated with glomerular bleeding, in contrast to RBCs with normal morphology due to nonglomerular bleeding. Examination should seek any external lesions of the perineum that might be related to the bleeding, most of which would be obvious with inspection. Abdominal examination for masses and tenderness is needed, as well as a check for any spinal or lower extremity abnormalities in the setting of a urinary tract infection (UTI) causing hematuria. Skin rashes may be present with immunologic renal bleeding.

Table 15-3 Differential Diagnosis of Hematuria in Girls | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

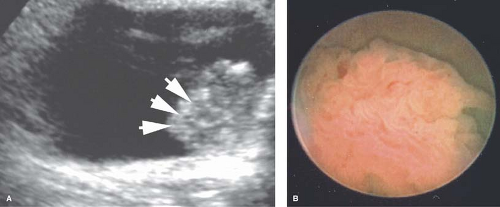

Ultrasound imaging of the entire urinary tract may be the best first step in the evaluation of hematuria and may be done acutely. There are few lesions of immediate importance that will not be detected by ultrasound. The bladder wall may be abnormal in cases of inflammatory hematuria, ranging from mildly thickened and irregular to having a pattern indistinguishable from a tumor. In the latter case it is occasionally necessary to perform cystoscopy and biopsy to determine the true nature of the lesion (Fig. 15-6). Most inflammatory bladder lesions are severely painful, while most tumors are not. In the setting of acute colicky flank pain consistent with a renal stone, renal ultrasound (US) imaging is replacing spiral CT imaging as the best modality to identify the presence, location, and size of a stone, as well as determining the degree of hydronephrosis.

Renal Colic

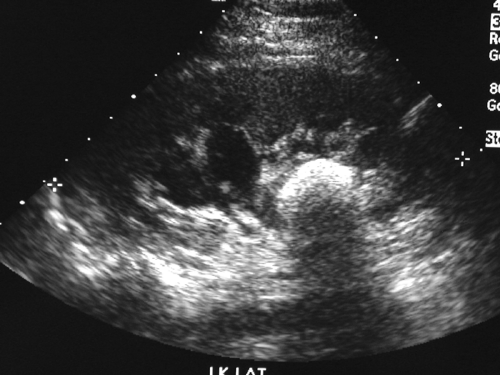

Flank pain that is intermittent and in waves is termed renal colic, usually due to passage of a renal stone. It may also be due to intermittent obstruction of the ureter, usually at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ). It may be associated with nausea and vomiting as well fever, as discussed below. The description of the pain is fairly typical in the older child, with it being sharp and stabbing with radiation along the flank into the inguinal region and even felt in the perineum, and coming in waves, often with complete resolution in between. The duration, intensity, and periodicity may be quite variable. Nausea and vomiting may be associated with colic and are a more objective finding indicating severe colic. Hematuria may be associated. A long-standing pattern of colic that might occur once or twice a month, often after meals or drinking, is suggestive of intermittent obstruction, often at the UPJ. Some of these children have already undergone extensive gastrointestinal evaluation. If stone is a possibility, renal US imaging is the most reasonable first-line testing, followed by

spiral CT (Figs. 15-7 and 15-8). US can usually identify stones in the renal collecting system and the proximal or distal ureter and if there is any hydronephrosis associated with them. It is a simple modality for serial follow-ups while waiting for stone passage.

spiral CT (Figs. 15-7 and 15-8). US can usually identify stones in the renal collecting system and the proximal or distal ureter and if there is any hydronephrosis associated with them. It is a simple modality for serial follow-ups while waiting for stone passage.

Flank Pain and Fever

The association of flank pain and fever is almost always due to pyelonephritis, renal parenchymal infection, or a severe cystitis. It may occur with nausea and vomiting and sepsis in younger children. While it is likely due to infection, the possibility of an obstructive lesion, either structural or due to a stone, must be considered, since these children may become seriously ill if not treated promptly. The prior history of similar episodes or a known diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux or nephrolithiasis is important to extract. The duration and pattern of progression should be determined. A urinalysis and culture are essential and should be done with great care, or with a catheter to avoid a misdiagnosis or contaminated specimen. Since therapy will usually be started immediately, the one culture obtained is very important. Early imaging is usually not essential but should be considered if antibiotic therapy is not effective in reducing the pain and fever within 48 hours. Further imaging will depend on the specific diagnosis and treatment response.

Perineal Mass

Figure 15-8. Ultrasound image of a large cystine calculus in the renal pelvis of a teenage girl with periodic flank pain. The size of the stone is masked by the acoustic shadow it produces. |

Diagnosis of an interlabial mass is based on the age of the child and the physical appearance of the lesion. Table 15-4 lists the

differential diagnosis of this condition. Each condition is characterized by its particular character and the clinical context. Urethral prolapse (see also Fig. 4-7 and Fig. 15-9) is typically in the African American child who may have a predisposing factor to abdominal straining such as constipation, coughing, or an indwelling bladder catheter (). This condition is characterized as a circumferential edematous ring of tissue around the urethral meatus and distinct from the vagina. Occasionally the tissue is necrotic or dusky. A prolapsed ureterocele is typically in younger children and may be dusky with congestion. It will be emerging from the posterior aspect of the urethral meatus and will be smooth and rounded. A tumor may emerge from the urethra, but more commonly is from the vaginal opening and may be irregular, typical of sarcoma botryoides (see Fig. 4-11). It may have been heralded by passage of tissue pieces. A paraurethral cyst is seen almost exclusively in the neonate and is a smooth structure adjacent to the urethra, but not involved with it, and has a milky white appearance under the superficial epithelium (Fig. 15-10; see also Fig. 4-8). An imperforate hymen is seen in the newborn as a midline smooth bulging posterior to the urethra, sometimes with a whitish appearance deep to the epithelium (Fig. 15-11; see also Fig. 4-10). The rare condition of a Gartner duct cyst is most often noted in infancy and is a smooth cystic structure emanating from the vagina laterally with an appearance of being filled with clear fluid (Fig. 15-12); alternatively, this could be an obstructed hemivagina with ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) as seen in Figs. 12-22, 12-52, and 12-53.

differential diagnosis of this condition. Each condition is characterized by its particular character and the clinical context. Urethral prolapse (see also Fig. 4-7 and Fig. 15-9) is typically in the African American child who may have a predisposing factor to abdominal straining such as constipation, coughing, or an indwelling bladder catheter (). This condition is characterized as a circumferential edematous ring of tissue around the urethral meatus and distinct from the vagina. Occasionally the tissue is necrotic or dusky. A prolapsed ureterocele is typically in younger children and may be dusky with congestion. It will be emerging from the posterior aspect of the urethral meatus and will be smooth and rounded. A tumor may emerge from the urethra, but more commonly is from the vaginal opening and may be irregular, typical of sarcoma botryoides (see Fig. 4-11). It may have been heralded by passage of tissue pieces. A paraurethral cyst is seen almost exclusively in the neonate and is a smooth structure adjacent to the urethra, but not involved with it, and has a milky white appearance under the superficial epithelium (Fig. 15-10; see also Fig. 4-8). An imperforate hymen is seen in the newborn as a midline smooth bulging posterior to the urethra, sometimes with a whitish appearance deep to the epithelium (Fig. 15-11; see also Fig. 4-10). The rare condition of a Gartner duct cyst is most often noted in infancy and is a smooth cystic structure emanating from the vagina laterally with an appearance of being filled with clear fluid (Fig. 15-12); alternatively, this could be an obstructed hemivagina with ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) as seen in Figs. 12-22, 12-52, and 12-53.

Table 15-4 Interlabial Mass in Children | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Incidental: Congenital Anomalies of the Urinary Tract

A variety of congenital renal anomalies may be noted on routine or directed evaluation of the pediatric reproductive organs. These include renal duplications, solitary kidney, hydronephrosis, renal ectopia, and renal anomalies of shape and position. Many of these conditions are clinically insignificant, but it is important to recognize their presence and document the specific condition for future reference. The important parameters to be identified are obvious and include hydronephrosis and its degree; the possibility of vesicoureteral reflux, manifest by febrile UTI; or hydronephrosis that arises during the examination. An ectopic kidney, if nonhydronephrotic, is seldom of any concern. It is important to recognize several important associations. One is that of a solitary normal kidney and a small, nondetected kidney that may be associated with an ectopic ureter and incontinence. These small dysplastic kidneys may be detected anywhere a normal kidney may be. Children with an ectopic ureter typically present with lifelong constant wetting of a small

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree