Delayed Puberty

S. Jean Emans

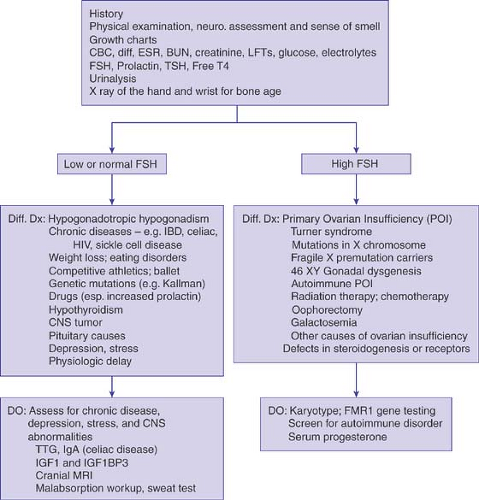

This chapter presents a practical approach to delayed sexual development, Chapter 9 provides the algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of amenorrhea, and Chapter 10 reviews abnormal uterine bleeding. Chapters 1 and 6 should be studied before an evaluation of any of these problems is undertaken. Gonadal development and embryogenesis are reviewed in Chapters 3 and 12. The distinction between delayed puberty and amenorrhea can be somewhat artificial because problems that cause pubertal delay can also cause amenorrhea. For example, a patient with 45,X/46,XX (Turner mosaic) or the patient with anorexia nervosa may present to the clinician with no sexual development, primary amenorrhea, or secondary amenorrhea. It is thus helpful for the clinician to think about a general approach to define the source of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis abnormality. The differential diagnosis of delayed puberty includes central causes (chronic disease, nutritional deficiency, hypopituitarism, and tumors), hypothyroidism, adrenal disorders, and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) or failure (Table 8-1 and Fig. 8-1). Physiologic delay of puberty (also known as “constitutional delay”) is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III) have shown that black girls enter puberty first, followed by Mexican American, and then white girls (1,2). The mean age of initiation of puberty for black, Mexican American, and white girls was 9.5, 9.8, and 10.3 years for breast development and 9.5, 10.3, and 10.5 years for pubic hair development, respectively (1). Early timing of pubertal maturation and breast budding in girls is associated with obesity and a higher body mass index (BMI) (3,4,5,6,7). (See also Chapters 6 and 7.)

Evaluation—History and Physical Examination

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for the evaluation of the adolescent girl with delayed puberty. A girl who has not experienced any pubertal development by the age of 13 years is more than 2 standard deviations beyond the normal age of initiating puberty and thus warrants a medical evaluation. For the exceptional girl who is known to have a debilitating chronic disease (see Chapter 27) or who is involved in ballet or a competitive endurance sport such as track or gymnastics that may be associated with a delay in pubertal development, the full diagnostic workup can be postponed until age 14 years, provided that other parameters of growth and development are compatible with the delay. Each girl should be observed for a steady progression of growth and pubertal development. A halt in maturation also signifies the need to do a thorough endocrine evaluation. Several illustrative case histories are included in the online version of this text.

The pertinent past history depends in part on the presenting complaint and may include the following:

Family history: heights of all family members (if short stature); age of menarche and fertility of sisters, mother, grandmothers, and aunts (familial disorders include delayed puberty, delayed menarche, androgen insensitivity, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, some forms of gonadal dysgenesis, inborn errors of metabolism such as galactosemia, and fragile X premutation carriers); history of ovarian tumors (e.g., gonadoblastomas in intersex disorders); and history of autoimmune endocrine disorders such as thyroiditis, diabetes, Addison disease, and autoimmune primary ovarian insufficiency.

Neonatal history: Maternal ingestion of androgens (can cause clitoromegaly); maternal history of miscarriages; birth weight; congenital anomalies; hernias; lymphedema (Turner syndrome); and neonatal problems such as hypoglycemia that can be suggestive of hypopituitarism.

Previous surgery (bilateral oophorectomy), radiation therapy, or chemotherapy.

Review of systems with special emphasis on a history of chronic disease, abdominal pain, diarrhea, headaches, neurologic symptoms, ability to smell, weight changes, disordered eating, caloric intake, sexual activity, galactorrhea, medications, substance abuse, emotional stresses, competitive athletics, acne, and hirsutism.

Age of initiation of pubertal development, if any, and rate of development.

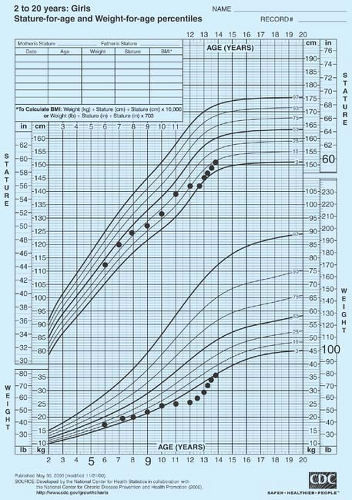

Growth data plotted on charts and midparental height calculated.

The physical examination involves a general assessment that includes height and weight, BMI calculation, blood pressure, palpation of the thyroid gland, and Tanner (Sexual Maturity Rating [SMR]) staging of breast development and pubic hair. The girl may have presented for a complaint of “no development” and yet the physical examination may reveal that her breast development is SMR 2; follow-up over the next 3 to 6 months may establish that the girl is in normal puberty. The presence of congenital anomalies should be assessed, including hernias, renal or spinal anomalies, or evidence of skeletal disproportion suggestive of chondrodysplasias. If abnormal body proportions are questioned during the visual assessment, measurement of the arm span and upper lower segment (U/L) ratios can be helpful. The arm span is measured from middle fingertip to middle fingertip. The lower segment is measured from the top of the pubic symphysis to the floor (the upper segment is height minus lower segment). In the child with normal proportions, the arm span is approximately the same as the height. The U/L ratio is around 0.95. Midline facial defects may be associated with hypothalamic–pituitary dysfunction. The somatic stigmata of Turner syndrome may be a clue to the diagnosis of delayed development (see p. 130). A neurologic examination is important in patients with delayed or interrupted puberty and includes an assessment of the ability to smell, funduscopic examination, and screening visual

field tests by confrontation (formal visual field tests may be indicated if a pituitary tumor is diagnosed). The presence of androgen excess (hirsutism, acne) or acanthosis nigricans should also be noted (see Chapter 11).

field tests by confrontation (formal visual field tests may be indicated if a pituitary tumor is diagnosed). The presence of androgen excess (hirsutism, acne) or acanthosis nigricans should also be noted (see Chapter 11).

Table 8-1 Differential Diagnosis of Delayed Puberty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In the initial examination of the adolescent with no pubertal development, the gynecologic assessment involves simple inspection of the external genitalia to determine if the girl has clitoromegaly and whether there is estrogen effect on the hymen and anterior vagina. The finding of a reddened, thin vaginal mucosa is consistent with lack of estrogen and delayed puberty; this is in contrast to the pink, moist vaginal mucosa consistent with estrogen effect. Because the etiology of pubertal delay likely results from an ovarian problem (e.g., Turner syndrome or primary ovarian insufficiency) or from a hypothalamic–pituitary problem (e.g., hypogonadotropic hypogonadism), an external genital examination usually suffices. In contrast, in the girl with normal pubertal development and primary amenorrhea, assessment of internal genital structure is essential to exclude a genital anomaly (see Chapter 9). However, in the nonobese prepubertal teenager, a simple rectoabdominal examination in the dorsal supine position will often allow palpation of the cervix and the uterus. If a pelvic ultrasound is obtained in a prepubertal adolescent girl, the uterus may not be well visualized and thus may be wrongly assumed to be absent. The ultrasound should be repeated in a pediatric center with experience in performing and interpreting ultrasounds in prepubertal girls.

In adolescents, assessment of the pattern of growth can yield valuable information (8,9,10,12,13,14,15,16,17). Accurate measurement using a stadiometer is critical to ascertain changes in growth patterns. Prepubertal growth rate is 2 to 2.5 in. per year with an increase at puberty and then closure of the epiphyses (see Chapter 6). Failure of statural growth for several years in the prepubertal girl may occur with gastrointestinal disease, weight loss, competitive athletics and dance, a chronic disease, or an acquired endocrine disorder. In conditions associated with poor nutrition, such as anorexia nervosa, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease, weight is typically affected more than height. The patient is usually underweight for her height. In contrast, patients with acquired hypothyroidism, cortisol excess (iatrogenic or Cushing syndrome), growth hormone (GH) deficiency, and Turner syndrome are typically overweight for height. Healthy obese girls typically advance through puberty at normal or early ages and are often above-average “growers.”

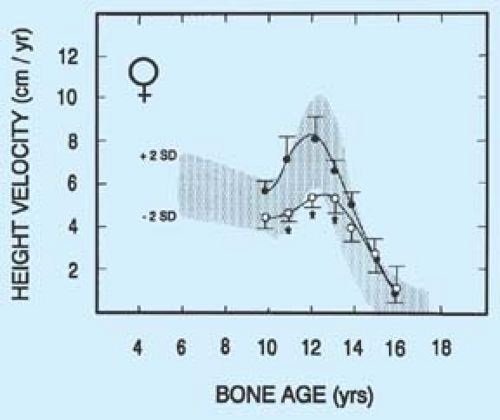

Girls who are involved in ballet or competitive endurance sports such as track and gymnastics may have a delay in pubertal development and growth (14,15,16,17) (Fig. 8-2) (see also Chapter 9). There is debate over whether this delay associated with undernutrition can result in lower final adult height. In a study of gymnasts and swimmers, Theintz and colleagues (16) noted that the growth spurt in gymnasts was suboptimal and associated with short stature (Fig. 8-3). Familial short stature and body type may be contributing factors to the observed results, and other studies have suggested more normal growth curves. However, inadequate nutrition from severe anorexia nervosa early in puberty can also impact growth velocity.

Evaluation–Laboratory Testing

After completing the history and physical examination and plotting height and weight data on the growth chart, the clinician should obtain laboratory tests including a complete blood count (CBC), urinalysis, and serum levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and/or free thyroxine (free T4), and prolactin. In girls with unexplained delayed puberty or symptoms of chronic illness, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is obtained, in addition to serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels, electrolytes, liver function tests, glucose, calcium, and other chemistry determinations, and a celiac screen (tissue transglutaminase [TTG] antibody and immunoglobulin A [IgA] level). A serum estradiol level can be helpful to confirm lack of estrogen effect, but a low level may not add much to the differential diagnosis. Similarly, a low dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) level is consistent with a delay in adrenarche and the appearance of

pubic hair. Also of note, although TSH is elevated in girls with hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, it may be in the normal range in girls with central hypothyroidism. For girls with poor linear growth, levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF-1–binding protein 3 (IGF-1BP3) can help screen for GH deficiency with the caveat that the levels should be compared to those of similar pubertal status. IGF-1 levels may be low in malnutrition and delayed development and do not necessarily indicate GH deficiency. Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) may rarely be positive in patients with tumors such as central nervous system (CNS) dysgerminomas, resulting in a false-positive pregnancy test.

pubic hair. Also of note, although TSH is elevated in girls with hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, it may be in the normal range in girls with central hypothyroidism. For girls with poor linear growth, levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF-1–binding protein 3 (IGF-1BP3) can help screen for GH deficiency with the caveat that the levels should be compared to those of similar pubertal status. IGF-1 levels may be low in malnutrition and delayed development and do not necessarily indicate GH deficiency. Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) may rarely be positive in patients with tumors such as central nervous system (CNS) dysgerminomas, resulting in a false-positive pregnancy test.

The differential diagnosis of delayed puberty can usually be divided on the basis of FSH levels into categories of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (high FSH levels, usually >30 mIU/mL, indicating ovarian insufficiency) and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (low or normal levels of FSH, indicating a hypothalamic problem) (Table 8-1 and Fig. 8-1) (8). Unless an elevated FSH level is suspected because of prior radiation, chemotherapy, or short stature, a single high FSH should be repeated (in 2 to 4 weeks) along with an estradiol level before a definitive statement about primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) is made to the patient and family (see Chapter 9). Low to normal levels of FSH (and luteinizing hormone [LH]) imply a CNS cause, for example, physiologic delay of puberty, hypothalamic dysfunction, a pituitary problem, stress, an eating disorder, chronic disease, or, rarely, a CNS tumor. In girls suspected to have Turner syndrome because of significant short stature and delayed puberty, the most important initial studies are the FSH level and karyotype.

A left hand and wrist radiograph for bone age will help determine how delayed the patient is and allow an estimation of final adult height (see Appendix 2). For example, hypothyroidism tends to delay bone age more than height age (the age at which the patient’s height would be on the 50th percentile on a growth chart). With constitutional delay, both bone age and height age are similarly delayed (unless the patient is also short genetically). Calculating midparental height is helpful in determining whether a girl’s predicted height is in a target range for her family. For girls, midparental height is [(mother’s height) + (father’s height – 5 in.)] divided by 2; 1 standard deviation (SD) is 2 in. (or 2 SD is 4 in.). It is extraordinarily helpful as the clinician is taking the history and performing the examination to think of the spectrum of possible diagnoses for delayed puberty or amenorrhea from the hypothalamus to the gonads. A stepwise evaluation using history, growth charts, physical examination, and limited laboratory tests will rule in and rule out the major causes of delayed puberty in adolescent girls.

Figure 8-2. Delayed development and poor growth in a ballet dancer. Medical and nutritional counseling resulted in marked improvement in growth rate. She was still prepubertal at age 13½. |

Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism

Low to Normal Follicle-stimulating Hormone (and Luteinizing Hormone) Levels

The majority of girls with delayed puberty will have low or normal FSH levels (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) from constitutional delay, undernutrition (Crohn disease, celiac disease), chronic illness, stress, disordered eating, weight loss, athletic competition, or endocrinopathies such as hypothyroidism. Other less common causes of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism include hypothalamic disorders such as Kallmann syndrome or a tumor, and pituitary problems such as a microadenoma or infiltrative disease. Other rare CNS problems include hydrocephalus (which more frequently is associated with early development), brain abscesses, and infiltrative lesions such as tuberculosis,

sarcoidosis, eosinophilic granuloma, Wegener granulomatosis, lymphocytic hypophysitis, and CNS leukemia. A normal physiologic delay in puberty is a diagnosis of exclusion.

sarcoidosis, eosinophilic granuloma, Wegener granulomatosis, lymphocytic hypophysitis, and CNS leukemia. A normal physiologic delay in puberty is a diagnosis of exclusion.

One of the most common causes of delayed puberty is poor nutrition. Caloric counts using food diaries and gastrointestinal evaluation are indicated in those with poor nutrition. Poor intake, malabsorption, and increased caloric requirements commonly occur in chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, HIV, renal disease, celiac disease, and Crohn disease (9,10,12). The diagnosis is frequently evident before puberty, but patients with Crohn disease may present with subtle manifestations such as growth failure in the teenage years. On careful history, most, but not all, patients with Crohn disease have a history of intermittent, crampy abdominal pain; diarrhea; or constipation. The ESR is usually, but not invariably, elevated, and mild anemia and hypoalbuminemia may be present as clues. Similarly, celiac disease may present with growth failure, delayed puberty, or amenorrhea and few other suggestive symptoms. If the patient is underweight for height and/or demonstrates poor weight and height gains, further gastrointestinal evaluation and a screening test for celiac disease are indicated before it is assumed that low caloric intake alone is responsible for the problem. Renal problems associated with impaired growth include renal tubular acidosis, glomerular diseases treated with corticosteroids, and end-stage renal failure.

Self-imposed caloric restriction and intermittent dieting are common among adolescent girls, many of whom view themselves as overweight. Society’s preoccupation with a thin physique may lead parents and children to restrict the diet inappropriately, causing weight loss or growth failure. Although anorexia nervosa is typically associated with amenorrhea, fear of obesity can cause significant growth failure in prepubertal children (13). However, it behooves the clinician to exclude a hypothalamic tumor, a malabsorptive state, and chronic disease in the prepubertal child with an apparent eating disorder. Children may also have inadequate access to food because of family psychosocial problems, alcoholism, drug abuse, lack of financial resources, or homelessness.

Delayed puberty and poor linear growth may be caused by endocrinopathies, including hypothyroidism, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and Cushing syndrome. Acquired hypothyroidism may have a subtle onset that may be missed except for the slowing of statural growth. The use of pharmacologic doses of corticosteroids to treat many medical diseases frequently causes an iatrogenic picture of Cushing syndrome. Substance abuse and psychological problems such as severe depression can be associated with an interruption of the pubertal process.

Hypothalamic–pituitary dysfunction may be caused by a number of inherited genetic defects that are increasingly being identified, including X-linked Kallmann syndrome 1 (one or more mutations on the KAL gene at Xp22.3) associated with lack of migration of the neurons responsible for gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release and the olfactory neurons (and thus anosmia); autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome (FGFR1 gene) with or without anosmia; receptor mutations across the hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal glands; GnRH receptor mutations (GNRH-R gene); mutations in G protein–coupled receptor-54 (GPR54 gene) and its ligand, kisspeptin; and leptin mutations (18,19). Some of these genetic disorders have been reported to be reversible and some of these defects may become apparent later in life, perhaps secondary to stress or other precipitants. Patients with hypothalamic dysfunction may also have midline craniofacial defects. Distinguishing isolated GnRH deficiency from delayed puberty may be difficult if the patient has not begun to show a normal postpubertal response to GnRH or GnRH analogs. Gonadotropin deficiency is likely in a prepubertal teen girl with normal or low FSH if bone age is >13 years, anosmia or panhypopituitarism is present, there is no sleep-associated increase in LH, and GnRH tests show a flat response (see Chapter 6) (20). Patients with delayed puberty or menarche frequently have other members of the family who have experienced a significant delay. This history alone, however, should not prevent an evaluation of girls with delayed development, since other conditions can be present. Follow-up is critical to make sure that normal puberty occurs, since one of these conditions may become apparent later.

Craniopharyngiomas typically present between the ages of 6 and 14 years and cause headaches, poor growth, delayed development, and diabetes insipidus. CNS dysgerminomas may also be detected by a positive HCG test. Children who have received cranial radiation for leukemia therapy may have abnormalities of GH secretion and may lack pulsatile GnRH secretion as well. Iron deposition from hemochromatosis and iron overload associated with transfusion therapy in thalassemia major can result in pubertal delay. Iron deposition in the patient with thalassemia may also cause hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, diabetes, cardiac failure, and/or pituitary dysfunction. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and obesity are also associated with the Laurence-Moon-Biedl and Prader-Willi syndromes. Medications, particularly antipsychotic drugs, can cause hyperprolactinemia (see Chapter 9).

Pituitary causes of interrupted development and irregular menses include hypopituitarism, either congenital or acquired, and tumors. Acquired hypopituitarism can result from genetic mutations (SOX2, LHβ gene, FSHβ gene), head trauma (21), hemorrhagic shock, pituitary infarction (e.g., sickle cell disease), and, rarely, an autoimmune process (22). Empty sella syndrome is rare in children, but can be associated with hypothalamic–pituitary dysfunction (23). The most common, but still rare, pituitary tumor in adolescence is a prolactinoma, which most typically causes primary or secondary amenorrhea (see section on Hyperprolactinemia in Chapter 9) (24). Pituitary adenomas that are not prolactinomas are not usually associated with amenorrhea and thus tend to be diagnosed at the time an imaging study is done for some other reason, such as headaches, or because tumor growth causes headaches or visual disturbances. Consultation with a pediatric endocrinologist and neurosurgeon is important.

Thus, the evaluation of the adolescent with low to normal FSH levels needs to focus on exclusion of a systemic disease, poor nutrition, a CNS disorder, or an endocrinopathy. Evidence of other chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, renal failure, diabetes, or liver disease should be assessed. If a hypothalamic or pituitary tumor is under consideration or if a girl has significantly delayed puberty, then evaluation should include cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Further neuroendocrine studies are important in the evaluation of patients with evidence of panhypopituitarism and some patients with tumors. Patients with a history of CNS radiation for leukemia should have their growth monitored carefully and neuroendocrine testing done if linear growth is abnormal. Formal visual field testing may be indicated in some patients with pituitary tumors. As noted in Chapters 6 and 9, girls with delayed puberty and especially low weight may not acquire normal bone mass, and thus should be

counseled about calcium and vitamin D intake and appropriate nutrition, and prescribed hormonal therapy as indicated. Bone density screening by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) should be considered in the patient with delayed puberty or long-standing (>6 months) amenorrhea.

counseled about calcium and vitamin D intake and appropriate nutrition, and prescribed hormonal therapy as indicated. Bone density screening by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) should be considered in the patient with delayed puberty or long-standing (>6 months) amenorrhea.

Hypergonadotropic Hypogonadism

High Follicle-stimulating Hormone (and Luteinizing Hormone) Levels

Adolescents with persistently elevated FSH levels have primary ovarian insufficiency POI, a term often replacing the more traditional term of premature ovarian failure (POF). However, debate continues on how to frame the medical conditions of patients with Turner syndrome who do not have any evidence of pubertal development or ovarian function and thus are indeed more appropriately termed as having “ovarian failure” because there is no chance of spontaneous return of function. POI is the broader term and includes patients who may have abnormal or absent X chromosomes such as Turner syndrome and specific mutations on the X chromosome but without stigmata of Turner syndrome, including POF1 and POF2A and 2B on the long arm and POF4 on the short arm (25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree