Vulvar Dermatology

Jonathan D.K Trager

The practitioner caring for children and adolescents with vulvar skin diseases (dermatoses) faces special challenges. First and foremost, there is the patient. She may have physical discomfort such as irritation, pruritus, or pain as well as emotional distress. She may be embarrassed due to the location of the problem, or worried about the possibility of cancer or a sexually transmitted disease. With chronic conditions such as lichen sclerosus, she may have concerns about the appearance of her vulva or of her ability to have normal sexual relations.

The next challenge for the practitioner is the parents or caregivers, who may have a number of concerns. They may feel guilt over their child’s severe diaper dermatitis (did we take good care of our child’s skin?). They may be distraught that their child did not confide in them earlier about her chronic vulvar symptoms. They may feel helpless to prevent their child’s skin disease from flaring up as often occurs with vulvar lichen sclerosus. They may have spoken or unspoken fears that their child’s vulvar irritation may be due to sexual abuse.

The final challenge to the practitioner is the diagnosis and management of the skin condition. The practitioner needs to be able to perform a quick but gentle and thorough examination, formulate a differential diagnosis, minimize the number of uncomfortable procedures such as cultures and biopsies yet perform them deftly when necessary, and prescribe a rational treatment plan. The diagnosis and treatment of vulvar skin disorders is often not well covered in medical education (1). Even for the dermatologist, vulvar skin disease represents a minuscule part of his or her training. In the primary care setting, vulvar examination may be omitted during a routine check-up because of concerns for patient modesty or embarrassment on the part of the patient and/or the clinician, and thus the patient does not benefit from reassurance that she has normal vulvar anatomy. Importantly, conditions that may not necessarily elicit a complaint may therefore go unnoticed; common examples are poor hygiene, vulvitis, labial adhesions, imperforate hymen, nevi, molluscum contagiosum, and condyloma acuminata (2,3). How often is vulvar irritation or pruritus attributed to a “yeast infection” (4) without consideration of the many causes of these symptoms, and without an examination? How often do girls with vulvar lichen sclerosus go untreated, sometimes for years, despite many visits to many doctors who prescribe yet another yeast cream? In one study of 74 girls with vulvar lichen sclerosus, the average delay in diagnosis was 2.2 years (5).

Practitioners who care for girls and young women must be prepared to deal with vulvar skin disease. Collaboration among disciplines is to be encouraged so that gynecologists, pediatricians, dermatologists, nurse practitioners, and other practitioners who care for girls and young women can offer their collective expertise. This chapter will survey common and uncommon yet important pediatric and adolescent vulvar skin problems as well as dermatoses that, while not strictly vulvar, may have predominant findings in the pubic area; together, these dermatoses are a microcosm of dermatology.

Is it Vulvovaginitis or a Vulvar Dermatosis?

The symptoms (irritation, pain, pruritus, dysuria) and signs (erythema, maceration, fissures, lichenification, vaginal discharge) of vulvovaginitis may overlap with those of vulvar dermatoses; hence, diagnostic difficulties may arise. An understanding of the etiology and treatment of vulvovaginitis is just as necessary for the dermatologist evaluating a vulvar skin disease as a working knowledge of vulvar dermatology is for the gynecologist or primary care provider evaluating introital irritation and vaginal discharge (see also Chapters 4 and 17).

Symptoms and signs of vulvovaginitis and vulvar dermatoses overlap because the anatomy of the two overlaps. Vulvitis (inflammation of the vulva) may involve not only mucosal surfaces of the vestibule but also keratinized skin of the labia minora, labia majora, and perineum. Vulvitis may occur alone or with vaginal inflammation (vaginitis). The discharge of vaginitis may in turn cause maceration of the vulva and a secondary vulvitis; again, keratinized skin may be involved. Conversely, diseases of the vulva that are dermatologic in nature (e.g., lichen sclerosus, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, irritant and allergic contact dermatitis) may cause mucosal inflammation due to pruritus and scratching. Complicating this is that treatment of one entity may cause the other. For example, treatment of candidal vulvovaginitis with a topical agent containing benzocaine may cause an allergic contact dermatitis of vulvar skin (6). Conversely, treatment of lichen sclerosus with a topical steroid may predispose to candidal vulvovaginitis. Confounding things even further, factors such as poor hygiene and local irritation could exacerbate symptoms of a skin disease such as atopic dermatitis.

The Etiology of Pediatric Vulvar Complaints—Gynecologic or Dermatologic, or Who Sees What?

The classic signs of vulvovaginitis—introital irritation and vaginal discharge—are said to account for 80% to 90% of outpatient visits of children to gynecologists (7). Much of this is attributed to nonspecific vulvovaginitis due to poor hygiene. The pediatrician, family medicine practitioner, or nurse practitioner often sees girls with vaginitis, labial adhesions, and vulvar pruritus due to pinworms. The dermatologist, on the other hand, is likely to see a different population of girls with vulvar complaints and thus diagnose specific dermatoses. Fischer reported on 130 prepubertal girls who presented with a vulvar complaint to a pediatric dermatology clinic. The most common diagnosis was atopic dermatitis followed by lichen sclerosus and psoriasis (Table 5-1) (8). In another study of 38 prepubertal girls with chronic vulvitis (excluding lichen sclerosus), genital examination showed that 71% had psoriasis and 24% had atopic dermatitis (4). In contrast, a dermatologic study by Paek and colleagues found that vulvar pruritus in children was mostly nonspecific in nature (9).

Reaction to this study prompted Fischer and Margesson to recommend a vigorous search for specific causes, rather than attribution to nonspecific causes, when the complaint in children is vulvar pruritus (10).

Reaction to this study prompted Fischer and Margesson to recommend a vigorous search for specific causes, rather than attribution to nonspecific causes, when the complaint in children is vulvar pruritus (10).

Table 5-1 Vulvar Disease in 130 Children with a Vulvar Complaint Presenting to a Pediatric Dermatology Clinic | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Rather than choose sides (nonspecific vs. specific causes of vulvar pruritus or vulvitis)—since either may be correct depending on the clinical situation—good rules of thumb to consider are as follows: (a) if what seems like nonspecific vulvovaginitis persists or is unresponsive to treatment, a primary vulvar skin disease should be considered; (b) if a primary vulvar skin disease seems evident but is not clearing, nonspecific causes such as hygiene issues as well as vaginitis should be reconsidered; and (c) if a vulvar skin disease seems apparent, the clinician should at a minimum consider those vulvar dermatoses that are commonly reported in children: atopic dermatitis, lichen sclerosus, and psoriasis.

Special Characteristics of Vulvar Skin

The unique features of vulvar skin play an important role in the appearance of normal skin findings (such as where sebaceous glands appear, where folliculitis can appear) and in the development of vulvar dermatoses. Vulvar skin is not uniform across all of its structures (11). Anatomic and physiologic differences exist between the skin covering the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and perineum. Even within these structures there are differences in skin content.

Mons pubis: Epithelium is cornified. (The stratum corneum, composed of dead skin cells, lipids, and water-binding organic chemicals, is the protective envelope of the skin that prevents exogenous material from entering the skin and prevents body water from escaping.) Sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and terminal hairs are present.

Labia majora, lateral aspect: Epithelium is cornified; sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and terminal hairs are present. Labia majora, medial aspect: Epithelium is cornified; sweat glands and sebaceous glands are present; terminal hairs may or may not be seen.

Labia minora, lateral aspect: Epithelium is cornified; sweat glands and sebaceous glands are present; no terminal hairs are seen. Labia minora, medial aspect: Epithelium is cornified or squamous mucosa; sweat glands may or may not be present; sebaceous glands are present; no terminal hairs are present.

Clitoris: Epithelium is squamous mucosa; no sweat glands, sebaceous glands, or terminal hairs are present.

Perineum: Epithelium is cornified; sweat glands and sebaceous glands are present; terminal hairs may or may not be present.

Vulvar skin is more prone to irritation than skin at other sites due to occlusion (skin to skin, skin to clothing), sweating, vaginal and urethral secretions, and mechanical trauma from masturbation and sexual activity. The surface pH of vulvar skin, like that of other intertriginous areas, is higher than that of nonintertriginous skin (more than one pH unit higher than forearm skin) (11). This, along with the increased moisture of vulvar skin, leads to a higher density of microbial colonization.

The barrier function of vulvar skin is relatively imperfect compared to other skin sites such as the forearm (11). The vulva is more permeable to water than nongenital skin, and studies of topical corticosteroids have shown a higher penetration in vulvar compared with nonvulvar skin. This impaired barrier function relative to nongenital skin means less protection of vulvar skin from irritants, especially in children who normally have relatively thin vulvar skin. However, if irritant dermatitis does develop on vulvar skin, it tends to heal more quickly than forearm skin upon removal or the irritant. This is also true for mechanical trauma (11).

Restoration of the barrier function of vulvar skin is an important theme in treating vulvar dermatoses.

Factors predisposing to vulvar dermatoses IN children and Adolescents

The anatomic, physiologic, and behavioral factors that predispose to vulvar dermatoses in children and adolescents overlap with those that predispose to vulvovaginitis (7). The thin labia minora and lack of labial fat pads and pubic hair in the child leaves the lower third of the vagina open and unprotected while the child squats. Additionally, the close proximity of the child’s vagina to the anus means the vulva and vagina are exposed to bacterial contamination from the rectum more frequently than in adults; vulvar dermatoses are thus more susceptible to bacterial contamination (relevant when surface cultures of skin lesions are performed) and to secondary bacterial infection. The relatively thin vulvar skin of the child also tends to have a more visible capillary network, making it appear more red naturally (Fig. 5-1) (7).

Vaginal and vulvar epithelium in children lack the protective effects of estrogen, making them more sensitive to irritation and infection (7). The more neutral or slightly alkaline pH of

vaginal epithelium makes it more susceptible to bacterial overgrowth; additionally, the vagina of the child lacks glycogen, lactobacilli, and sufficient antibody levels to help resist infection. Poor perineal hygiene with build-up of smegma and increased fecal bacteria on the perineum may cause irritation and pruritus. Conversely, overzealous cleansing can lead to irritant dermatitis with raw and denuded skin; similarly, excessive masturbation may cause vulvar irritation. Poor hand washing may inoculate environmental or respiratory pathogens. Use of tight-fitting and nonabsorbent clothing can lead to vulvar irritation and the excessive moisture may predispose to vulvovaginitis. In infants, occlusion from diapers and exposure to urine and feces cause irritant diaper dermatitis; an extreme form of this (known as Jacquet erosive dermatitis) may occur in children and adolescents with fecal incontinence from various causes (spina bifida, after surgery for Hirschsprung disease). Irritants such as bubble baths and harsh soaps may cause vulvovaginal irritation. Adolescent waxing and shaving of pubic hair can easily lead to mechanical or infectious (bacterial, viral, or fungal) folliculitis as well as autoinoculate herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, and human papillomavirus (HPV) across vulvar skin. An adolescent’s use of feminine hygiene products can cause irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy to latex condoms may manifest as a local or systemic reaction.

vaginal epithelium makes it more susceptible to bacterial overgrowth; additionally, the vagina of the child lacks glycogen, lactobacilli, and sufficient antibody levels to help resist infection. Poor perineal hygiene with build-up of smegma and increased fecal bacteria on the perineum may cause irritation and pruritus. Conversely, overzealous cleansing can lead to irritant dermatitis with raw and denuded skin; similarly, excessive masturbation may cause vulvar irritation. Poor hand washing may inoculate environmental or respiratory pathogens. Use of tight-fitting and nonabsorbent clothing can lead to vulvar irritation and the excessive moisture may predispose to vulvovaginitis. In infants, occlusion from diapers and exposure to urine and feces cause irritant diaper dermatitis; an extreme form of this (known as Jacquet erosive dermatitis) may occur in children and adolescents with fecal incontinence from various causes (spina bifida, after surgery for Hirschsprung disease). Irritants such as bubble baths and harsh soaps may cause vulvovaginal irritation. Adolescent waxing and shaving of pubic hair can easily lead to mechanical or infectious (bacterial, viral, or fungal) folliculitis as well as autoinoculate herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, and human papillomavirus (HPV) across vulvar skin. An adolescent’s use of feminine hygiene products can cause irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy to latex condoms may manifest as a local or systemic reaction.

Office Approach to Vulvar Dermatology

The methodical approach used for general dermatology (12) can easily be applied to pediatric and adolescent vulvar dermatology. The history should include the duration, rate of onset, and location of symptoms; family history (especially of skin disease and atopy); allergies to medications including sensitivity to topical agents; and previous diagnoses and treatments. Key components of the history are listed in Table 5-2. On clinical examination, it is important to determine if the eruption is limited to the vulva or is more widespread by doing a full skin examination. Determining the primary lesion and identifying the differential diagnoses are the next steps. Laboratory tests, if any, include skin biopsy; potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination for fungi; skin scraping for scabies; Gram stain; bacterial, fungal, and viral cultures; tape test for pinworm; cytology (Tzanck prep) for HSV or varicella-zoster virus; Wood’s light examination for pigmentary disorders; patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis; and blood tests. The treatment begins with general measures (comfort measures, good hygiene) and may need specific medications with close follow-up.

In examining for vulvar dermatoses it is imperative to have good lighting and good magnification. A goose neck lamp and a magnifying visor are ideal since they allow proper visualization while leaving both hands free for examination and procedures. Examination of the perianal area, buttocks, and gluteal cleft should not be forgotten; it is not unusual to find lesions of molluscum contagiosum and condyloma acuminata there. Psoriasis is common in the gluteal cleft and lichen sclerosus usually involves the perianal area. It may be challenging to examine the perianal area in the prepubertal child since this area is not completely visualized in the supine frog-leg position or prone position. A simpler method, which affords good perianal visualization and allows the child to help, is as follows: directly after examination in the supine frog-leg position, have her remain supine and ask her to pull her knees all the way up to her chest and hold each leg with a hand behind the knee. This generally allows good perianal relaxation and visualization; if not, gentle lateral traction of the buttocks should suffice.

Examination of extragenital skin may aid in diagnosing a perplexing vulvar dermatosis. Finding well-demarcated scaly plaques on the scalp, elbows, and knees along with pits in the fingernails and toenails may indicate that the vulvar rash is psoriasis (Fig. 5-2 A,B). Eczematous plaques of the antecubital and popliteal fossae should prompt consideration of the vulvar rash as atopic dermatitis. With hidradenitis suppurativa, axillary and inframammary (see section on Hidradenitis below) lesions are often present; these may be as bothersome to the patient as her inguinal lesions but she may not have known that they are all part of the same disease spectrum. To help confirm a diagnosis of scabies of the vulva, look for interdigital burrows and lesions of the breasts and buttocks. With Behçet disease, autoimmune blistering diseases, and erythema multiforme major, oral and ocular lesions may occur in addition to genital lesions.

Accurate diagnosis in vulvar dermatology is facilitated by accurate description of skin lesions. Even if the diagnosis is not readily apparent, a precise description may lead the way. A 16-year-old with “multiple, pink, umbilicated 2- to 3-mm papules on the labia majora” has molluscum contagiosum. An infant with “confluent vulvar erythema involving the inguinal folds and with satellite papules and pustules” has candidal dermatitis. A 6-year-old with “vulvar and perineal figure-of-eight hypopigmentation and atrophy with petechiae and fissures” has lichen sclerosus. An 18-year-old who shaves her pubic hair and has “honey-crusted papules and plaques” has impetigo. A 10-year-old with “well-demarcated, symmetric, pink plaques without scale” has psoriasis. A 4-year-old with “depigmented patches of the perianal area” has vitiligo.

Skin lesions of the vulva are easily influenced by the vulvar environment and prior treatment. The scale of psoriasis is typically not present on vulvar skin due to moisture and occlusion. The labia majora are prone to lichenification (thickening and hyperpigmentation) due to scratching. Prior topical treatment may cause irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. Topical steroid use may (a) partially mask tinea corporis (the term tinea incognito has been loosely applied to this), (b) cause a deeper more

recalcitrant fungal infection known as Majocchi granuloma (13), and (c) predispose to candidal vulvovaginitis.

recalcitrant fungal infection known as Majocchi granuloma (13), and (c) predispose to candidal vulvovaginitis.

Table 5-2 Dermatologic History in Children and Adolescents with a Vulvar Complaint | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The description of skin lesions should include mention of the primary lesion as well as any secondary skin changes (Table 5-3). Primary lesions are not necessarily the initial skin lesion but those that are most characteristic of the particular dermatosis. Proper description is critical at the outset as (a) the condition may change over time and with treatment, (b) it ensures appropriate documentation, (c) it aids in diagnosis, and (d) it allows better communication with a consulting dermatologist.

The finding of generally well-demarcated vulvar erythema should prompt consideration of a number of specific dermatoses (Table 5-4).

Therapeutics

General Measures

Eliminate possible causes: Identify and remove suspected causes of vulvar irritation (harsh soaps, bubble baths, feminine hygiene products, and suspected allergens).

Restore the skin barrier (14): In dry-skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, chronic contact dermatitis, and raw skin from overzealous hygiene, the skin has lost water and often epidermal lipids and proteins that maintain epidermal moisture. In these cases, recommend a mild cleanser and moisturizer such as Cetaphil Gentle Skin Cleanser and Cetaphil Moisturizing Cream. A ceramide-based moisturizer such as CeraVe Moisturizing Cream can help restore the normal skin barrier. Simple ointments containing petrolatum such as Thereplex or Aquaphor Healing Ointment may also be used to protect from further irritation and allow the skin to heal from within. For exudative inflammatory diseases, such as severe contact dermatitis, which pour out serum that leaches complex lipids and proteins from the epidermis, repeated cycles of wet compresses or sitz baths will eventually dry the lesions; once dry, moisturizer or barrier ointment can be applied. The challenge of using topical agents on the vulva is to moisturize and restore the skin barrier without causing further vulvar or vaginal irritation. If one agent stings or burns, it should be stopped and another, blander agent tried.

Relieve pruritus: Cool compresses and sedating antihistamines may help with this.

Review good vulvar hygiene: This should include measures such as wiping from front to back after bowel movements, wearing white cotton underpants, avoiding soapy bath water and bubble baths, using a nonsoap cleanser such as Cetaphil Gentle Skin Cleanser, wearing loose-fitting skirts, avoiding nylon tights or tight blue jeans, avoiding prolonged time in a wet bathing suit, and sleeping in loose clothing at night (see Chapter 4). A handout with good vulvar hygiene practices, such as the one produced by the North American Society of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, should be readily available to give to parents (www.naspag.org).

Medications

A core group of medications can be used for most pediatric and adolescent vulvar dermatoses.

Topical

Corticosteroids.

There are several dozen topical corticosteroids on the market and they are ranked in the United States from highest through lowest potency as group I (ultrapotent) through group VII (over the counter). Familiarity with only a few is needed for treatment of vulvar dermatoses. Topical corticosteroids are indispensable in the treatment of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen sclerosus, lichen simplex chronicus, and symptomatic pityriasis rosea.

For infants and small children and for mild inflammation at any age, a group VII agent such as hydrocortisone 1% or a group VI agent such as alclometasone 0.05% should suffice. For mild to moderate inflammation in the older child or adolescent, a group V agent such as Locoid 0.1% Lipocream is appropriate. With more moderate to severe inflammation, a group IV agent such as hydrocortisone valerate 0.2% is useful. For severe inflammation such as poison ivy or for lichen sclerosus, a group I agent such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment should be used.

Cream-based topical steroids have a high versatility and are useful for intertriginous areas. However, they usually contain a preservative that can sometimes cause stinging and irritation. For very dry lesions, an ointment-based corticosteroid helps

moisturize and restore the skin barrier. For weeping, exudative lesions, a gel-based corticosteroid will help with drying.

moisturize and restore the skin barrier. For weeping, exudative lesions, a gel-based corticosteroid will help with drying.

Table 5-3 Morphologic Diagnosis in Pediatric and Adolescent Vulvar Dermatology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 5-4 Common Causes of Generally Well-Demarcated Vulvar Erythema in Young Girls and Adolescents | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

Since vulvar skin has a greater permeability to topical steroids than nonintertriginous skin, the lowest-potency topical corticosteroid that can alleviate and control symptoms should be used. Limit the duration of therapy to 2 weeks, after which the child should be reevaluated.

Monitor for the side effects of topical steroid use on the vulva: burning/irritation/dryness caused by the vehicle (e.g., propylene glycol), skin atrophy, telangiectases, striae, purpura, hypopigmentation, and allergic contact dermatitis. Other considerations with topical steroid use include worsening of candidal dermatitis and HSV infection, ocular changes, hirsutism, and suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.

It is best to avoid combination corticosteroid/antifungal preparations such as clotrimazole/betamethasone dipropionate and nystatin/triamcinolone acetonide in children and adolescents for several reasons: (a) the corticosteroid component is usually too strong for what is needed; (b) you cannot taper the corticosteroid component and continue the antifungal component as you might if you prescribed two separate agents, thus possibly prolonging a fungal infection; and (c) these agents tend to be overused by clinicians (15), which leads to a self-reinforcing sense of safety for the patient, parent, and clinician; side effects such as atrophy and striae are thus more likely. If both components are needed—such as for severe vulvovaginal candidiasis—use two separate agents, one on top of the other, so that the corticosteroid can be stopped once the inflammation has improved while the antifungal agent can be continued until the eruption has cleared.

Antibiotics.

These include bacitracin, polymyxin B, neomycin, mupirocin, gentamicin, and the newer agent retapamulin. These can be used for minor cuts, fissures, and eroded or impetiginized rashes. Gentamicin cream may be used for “hot tub folliculitis” (Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Contact allergy to any of these agents is possible; neomycin in particular is a common sensitizer so it is best to avoid this agent entirely.

Antifungal agents.

These include the imidazoles, allylamines, ciclopirox, or a benzylamine for tinea cruris and tinea corporis of the mons pubis and buttocks, and the imidazoles, nystatin, and ciclopirox for candidal vulvitis.

Immunomodulators.

Tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.03% and 0.1% ointment and pimecrolimus (Elidel) 1% cream are used as second-line treatments for atopic dermatitis. These agents are beneficial for and commonly used off-label for vulvar psoriasis (16). Off-label treatment of other vulvar dermatoses (lichen sclerosus, genital lichen planus, vulvar lichen simplex chronicus) has been described (17); some concern, however, has been raised over their safety in lichen sclerosus (18).

Systemic

Steroids.

Prednisone or prednisolone is used for severe vulvar contact dermatitis such as poison ivy or allergy to benzocaine. Start with 1 to 2 mg/kg/d for 3 to 5 days, and then taper over 14 days.

Antibiotics.

Antibiotic coverage of a suspected vulvar bacterial infection must take into account skin as well as enteric pathogens. Groin abscesses due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are not unusual and should be considered if lesions are recurrent, large, or atypical or if systemic symptoms are present. Infection with P. aeruginosa is not uncommon after waxing procedures; a clinical indicator of this infection is multiple, large, painful, erythematous follicular papules and pustules.

Antifungal agents.

Fluconazole is used for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine may be used for severe tinea cruris or Majocchi granuloma. Watch age and dosing restrictions.

Biologic agents.

The tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab are used for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and have shown some efficacy in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa, vulvar Crohn disease, and vulvar ulcers of Behçet disease.

Vulvar Skin Biopsy

The vast majority of pediatric and adolescent vulvar skin diseases can be diagnosed clinically. Even lichen sclerosus, which has characteristic histopathologic findings, need not be biopsied in children if the diagnosis is certain (19). Reasons for not being too quick to perform a vulvar biopsy in children are straightforward: (a) the diagnosis can usually be made clinically, (b) empiric treatment may be tried before resorting to a biopsy, and (c) the thought of a biopsy may be scary to patient and parents alike. However, vulvar skin biopsy may be necessary under certain circumstances: when malignancy is suspected, when results have implications for the diagnosis and management of systemic illness or serious local disease (Behçet disease, Crohn disease), when an autoimmune blistering disorder is likely (childhood vulvar pemphigoid, chronic bullous disease of childhood), when the dermatosis has been recalcitrant to treatment and/or is causing significant symptoms, when biopsy of a vulvar ulcer is necessary, in diagnosing soft tissue tumors (after appropriate imaging is performed), and when HPV typing is considered necessary. When the situation is not urgent (as with most skin tags, nevi) but the parent or young patient would like eventual removal of a vulvar skin lesion, the procedure may be deferred until the patient is old enough to tolerate the procedure in the office.

There are four basic types of vulvar skin biopsy:

Shave biopsy: This is appropriate for lesions that are elevated above the plane of the skin (dermal nevi, condyloma acuminata). The lesion is elevated from the surrounding skin by infiltration with lidocaine with epinephrine; the epinephrine aids in hemostasis. The skin surrounding the lesion is stretched and supported using the thumb and forefinger of the free hand. In the other hand a no. 15 surgical blade is then used to shave the lesion at its base using long smooth strokes so as not to cause jagged edges. The final attachment of the lesion may need to be removed with scissors. Bleeding can be controlled with aluminum chloride or Monsel solution (use the latter with caution as it may cause staining of the skin).

Scissors excision: This is useful for pedunculated lesions such as skin tags, small lesions of condyloma acuminata, and dermal nevi. The lesion is elevated from the surrounding skin

by infiltration of local anesthetic. Gentle upward traction may be applied to the lesion with forceps; the lesion is then snipped off at the base with curved scissors. Bleeding can be controlled as for the shave biopsy.

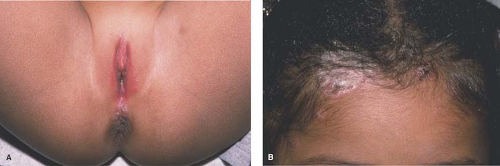

Punch biopsy: A full-thickness biopsy of skin can be obtained with a cylindric dermal punch biopsy. This technique is mainly used for superficial inflammatory dermatoses and bullous disease. Small pigmented lesions such as irregular nevi may be removed with a punch instrument; punches with tips in the shape of an ellipse are handy for this. Punch biopsy instruments come disposable and range in size from 1 mm to 8 mm; for inflammatory disorders, a 4-mm, or at the very least a 3-mm, punch biopsy should provide sufficient tissue for the dermatopathologist. After infiltration with local anesthetic, the thumb and index finger of the free hand are used to stretch the skin on either side of the lesion perpendicularly to the normal lines of skin tension (Langer lines). While the skin is held such, the other hand uses the dermal punch instrument in a continuous circular motion with gentle pressure until the desired depth is reached. The biopsy specimen may then be gently lifted with a forceps or a 30-gauge needle and carefully cut at the base with scissors. The prior stretching of the skin with the free hand allows the circular defect caused by the punch biopsy to relax into an ellipse, which can be more easily closed with sutures (Fig. 5-3 A,B). Use of absorbable sutures avoids the discomfort of suture removal. Healing by secondary intention is also appropriate for smaller biopsies and when suture removal would be traumatic.

If an autoimmune blistering disease (childhood vulvar pemphigoid, chronic bullous disease of childhood) is being considered, a separate specimen is needed for direct immunofluorescence studies. This can be done with a second punch biopsy; alternatively, a larger biopsy can be split in two with a no. 11 surgical blade (cut through the adipose side of the skin biopsy with the biopsy resting securely on a firm nonslip surface—the hard foil wrapper in which the suture came, placed on a Mayo stand, makes a handy surface for this).

Excisional biopsy: This is appropriate for deep inflammatory diseases and atypical pigmented lesions in which the entire depth of the lesion and appropriate margins must be reviewed. Local anesthetic is infiltrated and an elliptical excision is performed; templates are available to outline appropriate ellipse sizes. For larger lesions such as vulvar ulcers, an incisional biopsy may be done in which part of the ulcer is removed; the edge of the ulcer should be included in the biopsy. Larger excisions should undergo layered closure.

Younger children will usually undergo vulvar biopsy in the operating room under general anesthesia, especially if concomitant vaginal examination under anesthesia is necessary. Older children and adolescents may tolerate any of these types of skin biopsy in the office setting. However, the decision to perform a vulvar biopsy in the office should be made only after appropriate discussion and preparation with the parents and child and careful consideration of the child’s maturity level. Helpful adjuncts to a more successful office biopsy are distraction of the child during the biopsy (e.g., with a music player with earphones or a hand-held video game); prior application of EMLA (a eutectic mixture of local anesthetics, lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%) cream (may cause redness, burning, and edema on genital skin); warming the local anesthetic to body temperature and buffering the anesthetic with 8.4% sodium bicarbonate (1 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate to 10 mL of anesthetic solution) to reduce stinging (20); and injecting the local anesthetic slowly and using a 30-gauge needle (20).

Other Useful Dermatologic Procedures

Curettage

In this procedure, a dermal curette is used to scrape or scoop out a skin lesion. A dermal curette is an instrument with a loop, square, or cup tip. Tips range in size from 1 to 7 mm. A 3-mm loop-tip curette is invaluable for removing lesions of molluscum contagiosum; this technique can quickly be learned. Multiple lesions can be removed in a few minutes. EMLA cream may be applied beforehand to reduce pain; hemostasis is achieved with pressure and application of aluminum chloride (this may sting; applying the aluminum chloride before curettage seems to decrease stinging).

Liquid Nitrogen Cryotherapy

Freezing vulvar molluscum contagiosum and condyloma acuminata with liquid nitrogen is indispensable in the office setting and would benefit clinicians practicing office gynecology. Liquid nitrogen is stored in a large tank and may be dispensed into a liquid nitrogen spray unit. Alternatively, liquid nitrogen is dispensed into a small thermos or a Styrofoam cup; a cotton-tipped applicator may be dipped in the liquid nitrogen and then touched to the lesion. EMLA cream may be applied beforehand as with curettage. Lesions should be frozen for 15 to 30 seconds. The lesion eventually crusts and sloughs off. The patient should be warned that blistering may occur.

Normal Vulvar Findings That May Be Confused with Skin Disease

Sebaceous Glands

Sebaceous glands can easily be seen as an incidental finding along the medial and lateral aspects of the labia minora, as well as the medial aspects of the labia majora (21). Known as Fordyce spots, these glands are not associated with hair follicles. Some variability exists in their size; their number may range from a few (Fig. 5-4) to many and in some women may completely cover the inner labia minora and take on a “cobblestone” appearance. Their color may be white, yellowish, cream-colored, pink, or more pigmented in individuals with darker skin. Their function is to secrete sebum, an oily substance that lubricates genital skin. Fordyce spots also occur on the buccal mucosa and vermillion border of the lip; on the female areolae they are known as Montgomery tubercles.

Vestibular Papillomatosis

Vestibular papillomatosis describes the presence of multiple small (1 to 3 mm) papillae of the vulvar vestibule (21). Their pigmentation is similar to the patient’s general skin pigmentation (Figs. 5-5 and 5-6). The weight of evidence does not support a causal role for HPV. Thus, they should be considered physiologic and no treatment or biopsy is necessary.

Vulvar Dermatoses in Infancy

The most common skin problems of the infant vulva are irritant diaper dermatitis and candidal diaper dermatitis (22,23). In the understanding of just these two dermatoses, common themes of pediatric vulvar inflammatory dermatoses emerge: the ill effects of occlusion and moisture, the adverse actions on vulvar skin of feces and urine, the proliferation of microbes, the breakdown of the skin barrier, and treatment by restoration of the skin barrier and treating specific infections.

Less common but severe forms of irritant diaper dermatitis (Jacquet erosive dermatitis and granuloma gluteale infantum) should be on the clinician’s radar when the diaper rash is eroded or nodular. Other rare but serious infant vulvar dermatoses such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis and acrodermatitis enteropathica should also be in the clinician’s differential diagnosis. The

special case of vulvar hemangiomas is discussed because of the potential for significant complications.

special case of vulvar hemangiomas is discussed because of the potential for significant complications.

Irritant Diaper Dermatitis

Irritant diaper dermatitis is a nonspecific term that describes a spectrum of symptoms in the diaper area caused by inflammatory skin reactions. Four main factors contribute: wetness, friction, urine and feces, and microorganisms (22). Wet diapers result in excessive hydration and maceration of the stratum corneum. This leads to impairment of the already less than perfect barrier function of vulvar skin, which can result in enhanced penetration by irritants and microbes and makes vulvar skin more susceptible to frictional trauma. Mechanical trauma from skin to diaper contact further disrupts and macerates the stratum corneum and exacerbates barrier dysfunction. Fecal bacteria degrade urea in urine, thus releasing ammonia and increasing pH. Ammonia itself does not irritate intact skin; it may cause irritation by contributing to a higher local pH. Fecal lipases and proteases are activated by increased pH; this further disrupts the epidermal barrier. The warm, humid area of the perineum is ideal for the proliferation of microbes; in addition, the innate antimicrobial flora cannot survive the higher pH environment.

Perineal erythema is the hallmark of irritant diaper dermatitis (Fig. 5-7), often accompanied by maceration, erosions, and ulcerations. Unlike candidal diaper dermatitis, irritant diaper dermatitis usually spares the inguinal skin folds since these have less contact with the diaper and urine and feces. Similar findings will be seen in older girls and adolescents with urinary and fecal incontinence. The differential diagnosis includes candidal diaper dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and, in severe cases, rarer entities such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis and acrodermatitis enteropathica. No specific tests are necessary. If candidal superinfection is suspected, a surface skin culture can be obtained. Bacterial cultures may be difficult to interpret since fecal bacteria invariably will be recovered. However, a culture can be helpful if there is suspicion of pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes or if vaginitis is present, especially in the older child.

Treatment should focus on frequent diaper changes to maintain dryness and loose-fitting diapers to minimize contact between skin and urine and feces. Brief intervals without diapers are also beneficial. Cleansing should be gentle with an irritant- and fragrance-free soap or cleanser followed by patting dry and liberal application of a barrier preparation. Infant wipes usually consist of a nonwoven carrier that is soaked with an emulsion-type water or oil lotion. Preservative- and fragrance-free wipes should be chosen and are well tolerated in infants. Restoring the barrier function of perineal skin is vital for healing of irritant diaper dermatitis and is a continuous theme in the treatment of all vulvar inflammatory dermatoses. Pastes are the most desirable barriers followed by ointments; ointments are superior to creams and lotions, which are poorly adherent, are minimally occlusive, and may contain preservatives. The barrier pastes should be applied thickly and can be covered by petroleum jelly to avoid sticking to diapers. A group VI or VII topical corticosteroid ointment is often necessary in moderate to severe irritant diaper dermatitis. The agent can be applied twice a day for several days to a week. More potent topical corticosteroids as well as combination steroid/antifungal preparations should be avoided in infants (see Medications section). Secondary candidal infection is common, especially if the eruption has been present for several days or is severe. A topical azole antifungal agent, nystatin, or ciclopirox can be used. With treatment, irritant diaper dermatitis should resolve over 1 to 2 weeks. Failure of the eruption to resolve should prompt a complete review of all prescribed and actual treatment measures and consideration of other potential diagnoses.

Candidal Diaper Dermatitis

Candidal diaper dermatitis is a superficial fungal infection of perineal skin; vaginal involvement is not common in infants. Candida species may flourish in the wet, warm environment of the diaper area. The examination shows beefy red erythema on perineal skin, the buttocks, the lower abdomen, and inguinal areas (Fig. 5-8). Pinpoint vesicles and pustules—satellite lesions—may be seen at the periphery. An antecedent history of oral antibiotics may be obtained. Concomitant oral thrush and maternal nipple candidal infection may occur. A KOH preparation showing budding yeast and pseudohyphae

confirms the diagnosis; if KOH capability is not present, a surface culture can be obtained and empiric treatment begun.

confirms the diagnosis; if KOH capability is not present, a surface culture can be obtained and empiric treatment begun.

Treatment includes maintaining dryness with frequent diaper changes or not using diapers for short periods. An antifungal cream (an azole cream, nystatin, or ciclopirox) is used twice a day until the eruption clears. The addition of a topical antibiotic such as mupirocin ointment two to three times a day is effective for concomitant bacterial infection. The eruption may take 1 to 3 weeks to resolve. If erythema from irritation persists beyond 10 to 14 days, a brief course of topical hydrocortisone 1% cream may be applied followed in a few hours by application of the topical antifungal agent. Baby powders may help prevent recurrence by absorbing moisture.

Jacquet Erosive Dermatitis

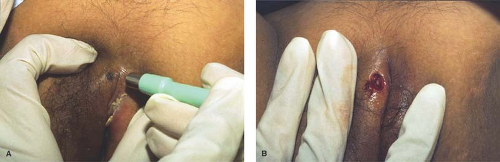

Jacquet erosive dermatitis is a form of severe irritant dermatitis (24,25). This occurs in infants in the setting of frequent loose stools, poor hygiene, and infrequent diapers changes, but has also been reported in older children and adolescents with urinary or fecal incontinence, for example, in the setting of spina bifida or after surgery for Hirschsprung disease (26,27). Lesions appear as punched-out ulcers with elevated, indurated borders (Figs. 5-9 and 5-10). Other dermatoses that cause erosions and ulcers should be considered including HSV infection, erosive candidiasis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. While the diagnosis can be made clinically, surface cultures for Candida, HSV, and bacteria may be obtained. Treatment is the same as for irritant diaper dermatitis, but this eruption make take longer to heal. Vigilance is required in home skin care. Close follow-up and reassurance are necessary as this eruption evokes a great deal of parental concern.

Granuloma Gluteale Infantum

This is a nodular eruption that may arise in the setting of irritant diaper dermatitis (28). The etiology is unknown but several factors have been suggested including Candida albicans, topical use of fluorinated corticosteroids, and as a response to long-standing infection. Lesions present with erythematous pseudoverrucous papules and nodules on groin and buttock skin. The differential diagnosis includes condyloma acuminata, HSV infection, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Treatment is the same as for irritant diaper dermatitis. Lesions should resolve over the course of weeks to months; residual scarring is not unusual.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is an inflammatory dermatosis that may occur in infants as well as in adolescents and adults. The exact cause of seborrheic dermatitis is unknown. The yeast Malassezia furfur has been implicated. In infants, perineal lesions appear as well-circumscribed, greasy, erythematous plaques (Fig. 5-11) (29). Scale tends to be less prominent in the diaper area due to occlusion and moisture but is commonly seen with involvement of the scalp, eyebrows, ears, and trunk. Adolescent involvement is usually of the scalp, eyebrows, glabella, and nasolabial folds. Treatment with a group VI or group VII corticosteroid ointment or lotion twice a day for 1 to 2 weeks should allow rapid healing. Moisturizing is also important for healing as well as for preventing recurrences. While recurrences are common, the overall eruption usually resolves by about 6 months of age.

If the eruption persists longer, consider the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, especially if there is a family history of atopy. There is no clear link between infantile and adolescent or adult seborrheic dermatitis. Infants with generalized seborrheic dermatitis and failure to thrive should be evaluated for complement C5 immunodeficiency.

If the eruption persists longer, consider the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, especially if there is a family history of atopy. There is no clear link between infantile and adolescent or adult seborrheic dermatitis. Infants with generalized seborrheic dermatitis and failure to thrive should be evaluated for complement C5 immunodeficiency.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

This is a group of idiopathic diseases characterized by proliferation of histiocytes and includes the classic descriptions of eosinophilic granuloma (of bone), Hand-Schüller-Christian disease (multifocal), and Letterer-Siwe disease (disseminated) (30). Solitary cutaneous disease presents with oral, perineal, vulvar (31), or retroauricular lesions. Skin lesions may also be seen in classic multifocal Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis (LCH) and acute disseminated LCH, which has multiorgan involvement including hepatosplenomegaly (32). A congenital form manifests as skin lesions at birth or during the early postnatal period; organ involvement may also occur. Skin lesions appear as closely set petechiae and yellow–brown papules topped with scale and crust; the papules may coalesce to form an erythematous, weeping, or crusted eruption (Figs. 5-12 and 5-13). Hemorrhagic infiltrated nodules and plaques may be seen as well as erosions and ulceration.

Perineal lesions of LCH may mimic seborrheic dermatitis; however, lesions of LCH tend to be hemorrhagic and more infiltrative in nature. Erosive candidiasis lacks hemorrhagic lesions. HSV infection of atopic dermatitis (eczema herpeticum) may cause ulcerated papules and plaques. Acrodermatitis enteropathica may cause perineal erosions. Skin biopsy will show the presence of CD1 a and S-100 surface markers and characteristic racquet-shaped bodies in the cytoplasm (Birbeck granules). Surface cultures for Candida species and HSV may be performed if those diagnoses are entertained. A systemic workup is needed to determine extent of the disease. Localized skin disease is treated with moderate to potent topical corticosteroids; other treatment modalities include psoralen plus ultraviolet A light therapy (PUVA) and ultraviolet B excimer laser. Multifocal and disseminated disease are treated with chemotherapy. The congenital form tends to resolve spontaneously within weeks to months. Prognosis is excellent for patients with single-system disease; multifocal and disseminated disease have variable prognoses (30).

Figure 5-12. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. (© DermAtlas; http://www.DermAtlas.org, with permission) |

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by zinc deficiency (33). The cause of acrodermatitis enteropathica is an inability to absorb sufficient zinc from the diet. Secondary zinc deficiency, as may occur with long-term parenteral nutrition without supplemental zinc or with chronic malabsorption, may have similar clinical findings. Skin findings include vesicobullous, eczematous, dry, scaly, or psoriasiform plaques symmetrically distributed in the perioral, acral, and perineal areas (Fig. 5-14) and also on the cheeks, knees, and elbows. Erosions and superinfection with C. albicans may occur. The clinical features as well as detection of a low plasma zinc level make the diagnosis. Treatment is with oral zinc therapy. The cutaneous manifestations of the disease are rapidly abolished with therapy. Measures used for the treatment of irritant dermatitis may help restore the skin barrier.

Hemangioma of Infancy

Hemangiomas are the most common tumor of infancy (34). They are benign neoplasms that arise from the rapid proliferation of endothelial cells. Risk factors include female gender, white race, premature birth, and maternal chorionic villous sampling. Hemangiomas of infancy (HOI) have been classified

as superficial, deep, or mixed; another classification looks at hemangiomas as localized, segmental, or indeterminate. Vulvar hemangiomas tend to be superficial and localized (Fig. 5-15). They may be associated with urogenital and anorectal anomalies such as anterior or vestibular anus, imperforate anus, and atrophy or absence of the labia minora.

as superficial, deep, or mixed; another classification looks at hemangiomas as localized, segmental, or indeterminate. Vulvar hemangiomas tend to be superficial and localized (Fig. 5-15). They may be associated with urogenital and anorectal anomalies such as anterior or vestibular anus, imperforate anus, and atrophy or absence of the labia minora.

Hemangiomas start within a few weeks after birth as a macular erythema, a telangiectatic patch, or an area of pallor; this undergoes a period of rapid growth followed by slow involution. Graying of the surface is an early sign of involution. Perineal hemangiomas are prone to ulceration and infection due to frictional and chemical trauma (35). Large perineal hemangiomas may interfere with micturition or defecation. Ulcerated hemangiomas (Fig. 5-16) may result in pain, infection, bleeding, and scarring. Bleeding may be recurrent or life-threatening (36). Hemangiomas have also been reported of the vaginal wall with resultant vaginal bleeding. The diagnosis of a vulvar hemangioma is usually apparent clinically. Vascular malformations are usually more poorly circumscribed, do not change in size rapidly but grow in proportion to the child, and do not involute. Tests are generally not needed for diagnosis. However, imaging tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help differentiate hemangiomas from other vascular lesions and may determine the depth of the lesion. The presence of multiple cutaneous hemangiomas should prompt a search for visceral hemangiomas. If a lesional biopsy is necessary, positive staining for the immunohistochemical marker glucose transporter protein 1 (GLUT-1) can be used to help distinguish HOI from other vascular tumors and malformations. Other markers that stain positive are the placenta-associated antigens FcγRII, merosin, and LeY (34).

Nonintervention is appropriate for most small lesions without functional impairment. Lesions with functional impairment or that ulcerate or bleed need treatment. Superabsorbent diapers will minimize contact of the hemangiomas with urine. For ulceration, wound care may be performed with compresses (saline or Burrow solution) followed by application of a topical antibiotic (metronidazole gel or mupirocin ointment), followed by application of petroleum jelly–impregnated gauze or a barrier ointment. Topical platelet-derived growth factor (becaplermin gel, Regranex) has shown healing in ulcerated hemangiomas (37); it is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this purpose. Other reported treatments include imiquimod (38) and topical and intralesional steroids.

Pain control may be needed with acetaminophen, acetaminophen with codeine, and judicious use of topical lidocaine as this agent carries the risk of systemic toxicity. Systemic steroids such as prednisone or prednisolone 2 to 3 mg/kg/d as an early morning dose have been used; if responsive, cessation of growth or the onset or involution should occur after about 2 weeks (34). Side effects of systemic steroids include hypertension, gastrointestinal upset and bleeding, adrenal suppression, and immunosuppression. Use of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas soared after growth arrest of an infant’s hemangiomas was incidentally noted when propranolol was started for

obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (34,39

obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (34,39

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree